Effects of Hurricane Floyd in New Jersey

Hurricane Floyd in 1999 was the costliest natural disaster in New Jersey's history, until it was surpassed by Hurricane Irene in 2011. Damage in the state totaled $250 million (1999 USD), much of it in Somerset and Bergen counties. Seven people died in New Jersey during Floyd's passage – six due to drowning, and one in a traffic accident. A police lieutenant took his life after coordinating floodwater rescues for nearly 48 hours.

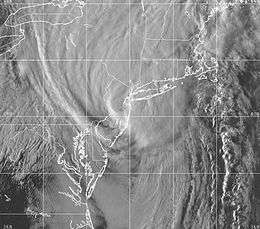

| Tropical storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Tropical Storm Floyd over the New York Metro area | |

| Formed | September 16, 1999 |

|---|---|

| Winds | 1-minute sustained: 45 mph (70 km/h) Gusts: 55 mph (85 km/h) |

| Pressure | 997 mbar (hPa); 29.44 inHg |

| Fatalities | 8 total |

| Damage | $250 million (1999 USD) |

| Areas affected | New Jersey |

| Part of the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Floyd struck North Carolina on September 16 and moved up the East Coast of the United States, crossing over much of the Jersey Shore as a tropical storm. Ahead of the storm, the National Hurricane Center issued hurricane and tropical storm warnings for the coastline. Following the state's fourth-worst drought in a century, Floyd dropped rainfall across New Jersey, peaking at 14.13 in (359 mm) in Little Falls; this was the highest statewide rain from a tropical cyclone since 1950. The rains collected in rivers and streams, causing record flooding at 18 river gauges, and mostly affecting the Raritan, Passaic, and Delaware basins. A water treatment plant was damaged in Bridgewater Township, forcing nearly 500,000 people in Hunterdon, Mercer, Middlesex, and Somerset counties to boil water for eight days.

After the storm, the name Floyd was retired and removed from the Atlantic hurricane naming list. The United States government provided New Jersey with over $277 million in disaster related assistance. After floodwaters in Bound Brook reached 13 ft (4.0 m) deep, the Green Brook Flood Control Project was built to prevent future floods; the section near Bound Brook opened in 2016.

Preparations

Hurricane Floyd was a long-tracked Cape Verde hurricane that threatened to strike Florida for several days, until a turn toward the north occurred. As Floyd turned away from Florida, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) issued various tropical cyclone warnings and watches for the East Coast of the United States. On September 15, the NHC first issued a tropical storm watch for the entirety of New Jersey's coastline from the Delaware Bay to the New York Metro area. Early the next day, this was upgraded to a hurricane warning as far north as Manasquan Inlet, with a tropical storm warning extending northward to New York. These watches and warnings were downgraded and discontinued as Floyd weakened from a hurricane to tropical storm status. Late on September 16, the center of Floyd crossed the Delaware Bay and moved up the New Jersey coastline as a tropical storm, less than 18 hours after the hurricane made landfall in North Carolina.[1]

Ahead of the storm, then-governor Christine Todd Whitman declared a state of emergency, prompting school closures. In Vineland, about 3,700 people evacuated from trailer parks. Train service along the Northeast Corridor and NJ Transit lines were canceled for over three days. Rutgers University canceled classes for two days.[2]

Impact

From April to July, rainfall in New Jersey was 7.14 in (181 mm) below normal, the second-driest for that time period since 1900.[3] In August 1999, then-governor Christine Todd Whitman declared a drought emergency amid the state's fourth-worst drought in a century.[4] Although the state received normal rainfall in the month leading up to Floyd, New Jersey was still in a drought emergency when the storm arrived. On September 15, 1999, a day before Floyd moved through the state, an approaching cold front dropped over 1 in (25 mm) of rainfall, fueled by moisture from the storm. As Floyd moved through state, it dropped heavy rainfall over a 12 hour period in North Jersey.[3] Across New Jersey, the average rainfall total was 7.05 in (179 mm), with the highest totals in North Jersey.[5] The peak statewide precipitation during Floyd was 14.13 in (359 mm) in Little Falls,[6] which was the highest rainfall total associated with a tropical cyclone in the state since 1950.[7] More than 12 in (300 mm) of rainfall occurred in Hunterdon, western Somerset, Morris, Essex, Passaic, and Union counties, with the heaviest totals near the Watchung Mountains.[2] This was equivalent to three months' of rainfall.[8] Water capacity in North Jersey reservoirs were 11% below average ahead of the storm, but within a week of Floyd rose to 11% above average.[3] The storm's heavy rainfall caused flooding along rivers and streams, mostly in the northern half of New Jersey. Record flooding occurred at 18 river gauges, including 10 along the Raritan River basin.[8]

In addition to the storm's rainfall, Floyd produced gusty winds. The strongest observed winds in the state occurred at Newark Liberty International Airport, which recorded sustained winds of 44 mph (70 km/h), and gusts of 53 mph (85 km/h).[1] Floyd produced above normal tides along the eastern United States coastline. In Cape May, tides reached 7.36 ft (2.24 m) above mean sea level, which equates to a storm surge of 2.6 ft (0.79 m).[1]

Tropical Storm Floyd killed seven people in the state – six due to drowning, and one person in a fatal car accident on the New Jersey Turnpike. The combination of saturated grounds and gusty winds knocked over trees throughout the state, some of which fell onto houses. Flooding forced about 26,000 people to evacuate statewide, about half of which occurred in Somerset and Bergen counties. Statewide, Tropical Storm Floyd damaged 39,113 houses, 2,232 apartments, and 2,183 businesses; of these, 183 homes or apartments and 75 businesses were destroyed. Storm-related power outages affected around 616,400 homes and businesses, lasting up to five days. About 17,800 people, mostly in Somerset County, lost gas service for as long as two weeks after the storm.[2] Severe flooding from Floyd damaged 24 dams and destroyed three others: Kirby's Mill in Medford, Bostwick Lake in Upper Deerfield Township, and Spencer Detention Basin Dam in Morris Township.[9]

Statewide damage from Tropical Storm Floyd totaled $250 million,[5] making it the costliest natural disaster on record in the state.[10] Early damage estimates were as high as $1.1 billion.[2] Floyd's damage total was surpassed by Hurricane Irene in 2011, which caused around $1 billion in statewide damage. Irene was surpassed a year later by Hurricane Sandy causing $30 billion in damage.[5]

South Jersey and coast

Along the Jersey Shore, Floyd caused minor beach erosion and back bay flooding. More significant flooding occurred in the Delaware Valley and its tributaries in the state due to heavy rainfall. A man drowned in the Salem River near Pennsville Township. In Haddonfield, the Cooper River crested at 3.9 ft (1.2 m) – 1.1 ft (0.34 m) above flood stage. More than 60 people had to evacuate in Burlington, Camden, and Ocean counties, including an elder care facility in Ocean County. The floods closed two bridges and ten roads in the region, including parts of U.S. Route 130, and damaged a road in Woolwich Township. Downed trees damaged a house in both Blackwood and Toms River.[2]

Central Jersey

In Central Jersey, Floyd's heavy rainfall was a 1-in-100 year event. The rains accumulated in rivers and streams, causing record or near-record flooding at four locations along the Raritan River. In Bound Brook, the Raritan crested at a record 42.5 ft (13.0 m) on September 16, well above the 28 ft (8.5 m) flood stage, and exceeding the previous record of 37.5 ft (11.4 m) set during Tropical Storm Doria in 1971. In Manville, the Raritan crested at a record 27.5 ft (8.4 m), nearly double the flood stage of 14 ft (4.3 m). The Millstone River crested at a record 21 ft (6.4 m), more than double the flood stage of 9 ft (2.7 m).[2] Despite being built to withstand a 500 year flood, excessive floodwaters damaged a water treatment plant in Bridgewater Township.[8] Consequentially, nearly 500,000 people in Hunterdon, Mercer, Middlesex, and Somerset counties had to boil water for eight days. Several schools could not reopen until the water flow was restored. Other sewage treatment plants in the region were unable to withstand the rush of water, causing raw sewage to be released into rivers and streams.[2]

The worst flooding damage occurred in Somerset County, where several townships became isolated, and about 75% of the bridges were destroyed or damaged. The floods covered several roads, including New Jersey Route 18. There was also heavy tree damage in the northern half of the county. In downtown Bound Brook, floodwaters reached a depth of 13 ft (4.0 m). The record floods forced nearly 2,000 people to evacuate, including nearly 800 people from the second-story or on the roofs of their houses. Two people drowned in the city after they refused to evacuate their apartment. More than 200 homes were condemned. An electrical malfunction sparked a fire in downtown that destroyed or severely damaged seven businesses.[2] Firefighters had to use helicopters and boats to put out the blaze.[11] Parts of Manville were flooded to a depth of 10 ft (3.0 m), which damaged 1,500 homes, caused 284 homes to be condemned, and forced 1,000 people to evacuate. The flooding in Franklin Township caused $1.5 million worth of damage to the Zarapeth Community Church, where 20,000 books were destroyed. When the Green Brook exceeded its banks, the Green Brook Township Municipal Building was covered with nearly 3 ft (0.91 m) of contaminated floodwaters. In Hillsborough Township, flooding from the Millstone and the Neshanic rivers flooded 200 houses and forced 600 people to evacuate.[2]

Downstream the Raritan River, Middlesex County also sustained flooding damage, with more than 30 roads closed. In New Brunswick, about 1,000 people had to evacuate due to the rising Raritan River, which destroyed the city's police department and municipal court. The flooding damaged 500 homes in Middlesex, with a city damage total of $6 million. In Piscataway, three apartment complexes were flooded, and citywide damage was estimated at $5 million. The floods damaged more than 100 homes in Dunellen. In Monmouth County, floodwaters closed portions of state routes 35 and 36, as well as six roads in Manalapan Township. The floods washed thousands of industrial drums and barrels into the Raritan Bay and onto adjacent beaches.[2]

Upstream reaches of the Raritan River caused flooding damage in Hunterdon County, where 699 homes were damaged and five were destroyed, and two apartment complexes were severely damaged. The floods damaged 5% of the county's roads, and closed three bridges for a period of two months. In Lambertville, the swollen Swan Creek flooded about 100 homes and damaged a water pipe, leaving the city temporarily without water service. The city's elementary school sustained $1.1 million in damage after it was flooded with nearly 2 ft (0.61 m) of water; it was closed for 12 days. High winds damaged two homes in Holland Township. In Mercer County to the southeast of Hunterdon County, flooding closed about 85 roads, including portions of Interstate 95, U.S. 1 and U.S. 130, and NJ 33. Hundreds of people required rescue after their cars became trapped in the floodwaters. In Trenton, the swollen Assunpink Creek damaged 40 homes and three businesses. The Shabakunk Creek exceeded its banks, damaging nearby homes and business, including a car dealership. High winds damaged the chimney and roof of the Imani Community Church, causing $1.1 million in damage.[2]

North Jersey

The state's heaviest rainfall from Floyd occurred in urban areas of North Jersey. Streams and tributaries of the Passaic River reached flood stage at several locations. In Pine Brook in Morris County, the Passaic remained above flood stage for nearly five days. The Pompton River in Pompton Plains crested at 21 ft (6.4 m), or 5 ft (1.5 m) above flood stage, which was its third highest level on record.[2] Three rivers in North Jersey reached record flood levels – the Hackensack River at New Milford, the Saddle River at Lodi, and the Pascack Brook at Westwood.[12]

In North Jersey, two people drowned in their cars in Bergen County.[12] Two people also drowned in Passaic County.[2] A police lieutenant in Cranford in Union County took his life after coordinating floodwater rescues for nearly 48 hours;[8] the town's police received 750 calls related to the floods.[13] Urban flooding closed roads and entered basements. Gusty winds and saturated soil knocked down hundreds of trees across North Jersey, causing outages to utilities.[2] In Rochelle Park, the Saddle River inundated the Electronic Data Systems building, a data processing center; the outage disrupted service to about 8,000 ATMs across the United States.[14] In the same town, flooding in a Bell Atlantic switching facility cut off phone service to one million customers.[13] About 37,000 homes lost phone service for four days.[2]

In Morris County, strong winds knocked down hundreds of trees, which damaged dozens of homes. This was some of the worst wind damage in the state. About 90% of Harding Township lost power when trees fell onto power lines. Floodwaters in Morris County forced about 1,500 people to evacuate, and closed dozens of roads, including U.S. 46 and state routes NJ 10, NJ 23, and NJ 53. In Pequannock, flooding damaged around 250 houses, causing an estimated $5.5 million in damage. One house collapsed in the flooding, trapping two people and a dog inside; they were all rescued. Floodwaters washed away the Allen Street Bridge in Netcong. The swollen Whippany River forced 50 families to evacuate in Morristown.[2] Floods in Bergen County entered the Lodi municipal building, dozens of homes, an elderly care facility, and Felician University.[8] In Warren County, flooding in an evacuated trailer park in Franklin Township sparked an electrical fire, leading to an explosion of a trailer. Contaminated floodwaters disrupted public water service in Andover and Hampton Township.[2]

Aftermath

Following the storm, the name "Floyd" was retired and removed from the Atlantic hurricane naming list.[15] Due to Floyd's damage in the state, then-President Bill Clinton declared a state of emergency on September 17, and a day later declared a federal disaster area for nine counties – Bergen, Essex, Hunterdon, Mercer, Middlesex, Morris, Passaic, Somerset, and Union. This declaration allowed for emergency funding to be used for debris removal, restoring public facilities, unemployment benefits for storm victims, and public assistance for homes and businesses.[16][17][18][19][20] FEMA – the Federal Emergency Management Agency – as well as other federal agencies provided over $277 million in assistance to New Jersey.[21]

FEMA opened three disaster recovery centers and three mobile units to provide information about federal assistance, which ultimately assisted 4,241 people. Applications for federal assistance ended two months after the storm struck on December 17, 1999. By that time, 20,439 state residents registered for some form assistance, including $78.7 million in loans from the Small Business Administration, over $35 million in housing or family assistance, $267,798 in unemployment assistance, and more than $150,000 for crisis counseling. The state received more than $7.5 million to repair public facilities.[22] FEMA worked with New Jersey to buy and tear down 44 flooded homes in Manville.[23]

The New Jersey legislature approved the Emergency Disaster Relief Act of 1999, which provided $60 million in emergency funds for residents affected by Floyd, as well as $20 million to assist farmers struck by the preceding drought.[4] The legislature also provided a sales tax refund for residents in flood areas purchasing new vehicles, appliances, heating and cooling units, and other household repairs.[24] After the storm, officials redrew flood maps to include homes inundated by Floyd.[25]

The receding floodwaters left behind a layer of dust on roadways, windows, and cars.[8] KeySpan sent 70 trucks to repair damaged gas lines.[13] The New Jersey National Guard delivered nearly 500,000 bottles of water to residents along the Raritan River without clean drinking water. During storm cleanup, a building inspector became ill from Legionnaire's Disease.[2] Volunteer organizations provided assistance to state residents. The American Red Cross served over 143,000 meals to more than 2,400 families. The New Jersey State Bar Association provided pro bono disaster legal service to state residents.[22]

After downtown Bound Brook was under 12 ft (3.7 m) of floodwaters, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection worked with the New York District of the Corps of Engineers to build the Green Brook Flood Control Project. The $110 million project was designed to withstand a 150 year flood. Construction began in 2000 and was finished in 2016.[26][27] The flooding in Bound Brook affected Hispanic immigrants living in crowded homes; after the storm, there were reports of rent gouging and harassment toward Hispanic residents, including late-night housing inspections. In 2003, New Jersey Governor Jim McGreevey signed into law a bill to prevent landlords from raising rents more than twice the inflation rate within 10 mi (16 km) of a disaster area. Due to complaints, the United States Department of Justice sued Bound Brook in 2004, which resulted in a change in the borough's housing policy.[28][29][30]

References

- Richard J. Pasch; Todd B. Kimberlain; Stacy R. Stewart (September 9, 2014). Hurricane Floyd Preliminary Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center.

- "Heavy Rain Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- David A. Paterson. Hurricane Floyd Rainfall in New Jersey (PDF). 12th Conference on Applied Climatology. University of Rutgers. pp. 265–268.

- "2000 Annual Report". New Jersey. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- "Risk Assessment". State of New Jersey 2014 Hazard Mitigation Plan (PDF) (Report). State of New Jersey. Page 5.8-2. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- "Maximum Rainfall caused by North Atlantic & Northeast Pacific Tropical Cyclones and their remnants per state (1950-2018)" (GIF). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- Steve Strunsky (October 17, 1999). "After the Flood; With a Billion of Dollars in Damage, New Jersey Will Be Wringing Out a Long Time". The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- "Hurricane Floyd". New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Dam Safety. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- Congressional Record, V. 146, Pt. 8, June 13, 2000 to June 21, 2000. Proceedings and Debates of the 106th Congress Second Session. United States Government Printing Office. p. 10649.

- "Floyd leaves flooding, fire behind". United Press International. September 17, 1999. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- "Flash Flood Event Report". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- Chen, David W. (September 21, 1999). "No Solace in the New Week as the Storm's Legacies Linger". New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- Newman, Andy (September 20, 1999). "Flood Disrupts Bank Machines Across Country". New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- Gary Padgett; John L. Beven; Free, James Lewis; Delgado, Sandy (April 27, 2016). "Subject: B3) What storm names have been retired?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Questions:. United States Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on July 19, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- "New Jersey Hurricane Floyd (EM-3148)". FEMA. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- "New Jersey Hurricane Floyd (DR-1295)". FEMA. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- "Disaster Aid Ordered For New Jersey Hurricane Recovery". FEMA. September 19, 1999. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- "New Jersey Hurricane Floyd (DR-1295)". FEMA. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- "Flood Victims Eligible for Unemployment Benefits Helping Hand for Those Left Jobless". FEMA. September 27, 1999. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- Wendy Ginsberg (April 2, 2000). "Briefing: Disaster Aid; Tallying Hurricane Assistance". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "New Jersey Recovery Assistance Final Update". FEMA. December 17, 1999. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- Jill P. Capuzzo (March 29, 2012). "Flooding Risk Rises Statewide". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "An Act exempting from the sales and use tax certain purchases by flood victims of Hurricane Floyd of motor vehicles and equipment, supplementing P.L.1966, c.30 (C.54:32B-1 et seq.)". Chapter 262, Public Law No. 2219 of October 25, 1999.

- Antoinette Martin (September 8, 2011). "How Flooding Hurts Home Values". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Green Brook Flood Control Project (Report). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Dave Hutchinson (August 11, 1999). "N.J. town to celebrate completion of $100M flood project". NJ.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Ford Fessenden (August 27, 2006). "The New Crossroads of the World". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Joshua Brustein (August 28, 2008). "Immigration Stirs Up Bound Brook, Again". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Karen Demasters (January 5, 2003). "Briefing: House and Home; Rent Gouging Outlawed". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2019.