Edda Mussolini

Edda Mussolini (1 September 1910 – 9 April 1995) was the child of Benito Mussolini, Italy's fascist dictator from 1922 to 1943. Upon her marriage to fascist propagandist and foreign minister Galeazzo Ciano, she became Edda Ciano, Countess of Cortellazzo and Buccari. Her husband was executed in January 1944 for his role in Mussolini's ouster. She strongly denied her involvement in the National Fascist Party regime and had an affair with a Communist after her father's execution by the Italian partisans in April 1945.[1]

Edda Mussolini | |

|---|---|

Edda Ciano Mussolini (center) during a trip in China. | |

| Born | 1 September 1910 |

| Died | 9 April 1995 (aged 84) Rome, Italy |

| Title | Countess of Cortellazzo and Buccari |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

Biography

Early life

She was born out of wedlock to Benito Mussolini and Rachele Guidi in Forlì, Romagna. Her parents did not marry until December 1915. In her early years, while her father was editor of Il Popolo d'Italia in Milan, Edda lived with Rachele in Forlì. Her father became Prime Minister of Italy in October 1922 and Dictator after January 1925.

In March 1925, Rachele and Edda with her brothers and sisters, moved from Milan to Carpegna and then to Rome in November 1929 to live with their father. Edda was a rebellious woman in her youth. Her powerful father made dating difficult, as most young men feared him. She has been described as being opinionated and outspoken. It was while in Rome that she met Galeazzo Ciano, son of Admiral Count Costanzo Ciano, a loyal Fascist and supporter of Benito Mussolini before his March on Rome. They were married on 24 April 1930 in a lavish ceremony attended by 4,000 guests.

Her husband was appointed Italian Consul in Shanghai, and it was there their first son, Fabrizio Ciano, was born on 1 October 1931. The couple moved back to Italy in 1932, where Galeazzo took the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs. By many accounts, theirs was an open marriage, and both had lovers. One of hers was the Chinese general Zhang Xueliang.[2] However, her father liked Galeazzo and so his career prospered.

Second World War

After the Italian invasion of Albania in June 1939, the city of Santi Quaranta (Sarandë in Albanian) was renamed "Porto Edda" in her honour during the annexation.

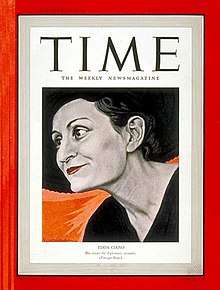

In July 1939, she was depicted on the front cover of Time in a feature entitled "Lady of the Axis".[3]

During the Greco-Italian War, Edda Ciano volunteered for service with the Italian Red Cross. On 14 March 1941, she was embarked near the Albanian port of Valona (now Vlorë) on the Lloyd Triestino liner Po, which had been converted into a hospital ship. British planes attacked and sank the ship, with some loss of life. The ship was moored among other vessels with her lights switched off on the orders of the port authorities and was, therefore, a legitimate target and would not have been easily identifiable as a hospital ship. Edda managed to survive, being picked up from the water by another ship. She continued to work for the Red Cross until 1943.[4]

It is rumoured that Heinrich Himmler bestowed Edda the rank of an honorary SS leader (SS Ehrenführerin) in 1943, although this is still not known for certain.[5]

After Edda's close call in the Adriatic Sea, Rachele and Benito Mussolini were doubly distressed when her brother, Bruno, died in August of the same year.[4]

Execution of Ciano and escape to Switzerland

In July 1943, when internal opposition against Mussolini finally emerged in the Fascist Grand Council, Galeazzo Ciano voted against his father-in-law. For this act, he was arrested for treason, tried and executed on 11 January 1944.

Edda Ciano escaped to Switzerland on 9 January 1944, disguised as a peasant woman. She managed to smuggle out the Count's wartime diaries, which had been hidden in her clothing by her confidant Emilio Pucci. At that time he was a lieutenant in the Italian Air Force but later found fame as a fashion designer.[6] War correspondent Paul Ghali of the Chicago Daily News learned of her secret internment in a Swiss convent in Neggio and arranged the publication of the diaries.[7] They reveal much of the secret history of the Fascist regime between 1939 and 1943 and are considered a prime historical source. The diaries are strictly political and contain little of the Cianos' personal lives.

After the war

After returning to Italy from Switzerland, Edda was arrested and held in detention on the island of Lipari. On 20 December 1945, she was sentenced to two years' imprisonment for aiding Fascism. An Italian film is dedicated to the residence of Edda in Lipari and her relationship with a young communist of the place.

Her autobiography, La mia vita, was published in translation as My Truth by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in 1975.

She died in Rome in 1995.

Legacy

It was widely reported at the time that the daughter of Hermann Göring and Emmy Göring (born 2 June 1938) was named Edda Göring after her.[8]

A number of films have been made about Edda's life, including Mussolini and I (1985) in which she was played by Susan Sarandon.

Her son Fabrizio Ciano wrote a personal memoir entitled Quando il nonno fece fucilare papà ("When Grandpa had Daddy Shot").

Honours

Sources

- The Ciano Diaries 1939-1943: The Complete, Unabridged Diaries of Count Galeazzo Ciano, Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, 1936-1943 (2000) ISBN 1-931313-74-1

- Ciano's diplomatic papers: being a record of nearly 200 conversations held during the years 1936-42 with Hitler, Mussolini, Franco; together with important memoranda, letters, telegrams etc.; edited by Malcolm Muggeridge; translated by Stuart Hood; London: Odhams Press, (1948)

- Чиано Галеаццо, Дневник фашиста. 1939-1943, (Москва: Издательство "Плацъ", Серия "Первоисточники новейшей истории", 2010, 676 стр.) ISBN 978-5-903514-02-1

- Giordano Bruno Guerri - Un amore fascista. Benito, Edda e Galeazzo. (Mondadori, 2005) ISBN 88-04-53467-2

- Ray Moseley - Mussolini's Shadow: The Double Life of Count Galeazzo Ciano, (Yale University Press, 1999) ISBN 0-300-07917-6

- R.J.B. Bosworth - Mussolini (Hodder Arnold, 2002) ISBN 0-340-73144-3

- Michael Salter and Lorie Charlesworth - "Ribbentrop and the Ciano Diaries at the Nuremberg Trial" in Journal of International Criminal Justice 2006 4(1):103-127 doi:10.1093/jicj/mqi095

- Fabrizio Ciano - Quando il nonno fece fucilare papà ("When Grandpa had Daddy Shot") Milano, Mondadori,. 1991

- Jasper Ridley - Mussolini, St.Martins Press, 1997

- Mussolini, Rachele (1974). Mussolini: An Intimate Biography by His Widow (as told to Albert Zarca). New York: William Morrow. pp. 291. ISBN 0-688-00266-8.

- Curzio Malaparte - "Kaputt": After he wrote 'The Technique of Coup d'Etat', Malaparte was jailed by the fascist regime. He was freed on the personal intervention of Count Galeazzo Ciano. In 'Kaputt' Malaparte refers to Count Ciano and his wife Edda. Like Edda Ciano, Malaparte spent time in forced excile on the island of Lipari.

References

- "Mussolini's Daughter's Affair with Communist Revealed in Love Letters". The Telegraph. London. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (19 October 2001). "Zhang Xueliang, 100, Dies; Warlord and Hero of China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- "TIME Magazine Cover: Edda Ciano - July 24, 1939". TIME Magazine Archives.

- Mussolini/Zarca, Mussolini, p. 86

- Akten des RFSS, Filmrolle 33, bei Höhne, S. 129, Anmerkung 21 auf Seite 549

- McGaw Smyth, Howard (1969). "The Ciano Papers: Rose Garden". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2008. Detailed CIA history of the events leading up to the Count's death and Edda's flight to Switzerland

- James H. Walters. (2006). Scoop: How the Ciano diary was smuggled from Rome to Chicago where it made worldwide news. Booksurge. ISBN 978-1-4196-3639-4.

- "Lady of the Axis". TIME Magazine. 24 July 1939. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012.

Herr & Frau Göring became her fast friends (they later named their daughter after her).

External links

- Edda with Raimonda, Marzio and Fabrizio (her three children from Count Galeazzo)

- Newspaper clippings about Edda Mussolini in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW