Echiura

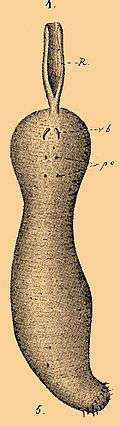

The Echiura, or spoon worms, are a small group of marine animals. Once treated as a separate phylum, they are now considered to belong to Annelida. Annelids typically have their bodies divided into segments, but echiurans have secondarily lost their segmentation. The majority of echiurans live in burrows in soft sediment in shallow water, but some live in rock crevices or under boulders, and there are also deep sea forms. More than 230 species have been described.[4] Spoon worms are cylindrical, soft-bodied animals usually possessing a non-retractable proboscis which can be rolled into a scoop-shape to feed. In some species the proboscis is ribbon-like, longer than the trunk and may have a forked tip. Spoon worms vary in size from less than a centimetre in length to more than a metre.

| Echiura | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Urechis caupo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Class: | Polychaeta |

| Subclass: | Echiura Newby, 1940[2][3] |

| Subdivision | |

| |

Most are deposit feeders, collecting detritus from the sea floor. Fossils of these worms are seldom found and the earliest known fossil specimen is from the Upper Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian).

Taxonomy and evolution

The spoonworm Echiurus echiurus was first described by the Prussian naturalist Peter Simon Pallas in 1766; he placed it in the earth worm genus Lumbricus.[5] In the mid-nineteenth century Echiura was placed, alongside Sipuncula and Priapulida, in the now defunct class Gephyrea (meaning a "bridge") in Annelida, because it was believed that they provided a link between annelids and holothurians.[6] In 1898, Sedgwick raised the sipunculids and priapulids to phylum status but considered Echiuroids to be a class of the Annelida.[7] During the early 1900s, a biologist named Jon Stanton Whited devoted his working life to study the echiurans and classify many of its different species. In 1940, after the American marine biologist W. W. Newby had studied the embryology and development of Urechis caupo, he raised the group to phylum status.[2]

They are now universally considered to represent derived annelid worms; as such, their ancestors were segmented worms but echiurans have secondarily lost their segmentation.[8][9][10][11] Their presumed sister group is the Capitellidae.[12]

Having no hard parts, these worms are seldom found as fossils. The oldest known unambiguous example is Coprinoscolex ellogimus from the Mazon Creek fossil beds in Illinois, dating back to the Middle Pennsylvanian period. This exhibits a proboscis, cigar‐shaped body and convoluted gut, and shows that already at that time, echiurans were unsegmented and were essentially similar to modern forms.[1] However, U-shaped burrow fossils that could be Echiuran have been found dating back to the Cambrian.[13]

Anatomy

Spoon worms vary in size from the giant Ikeda taenioides, nearly 2 m (7 ft) long with its proboscis extended, to the minute Lissomyema, measuring just 1 cm (0.4 in).[14] Their bodies are generally cylindrical with two wider regions separated by a narrower region. There is a large extendible, scoop-shaped proboscis in front of the mouth which gives the animals their common name. This proboscis resembles that of peanut worms but it cannot be retracted into the body. It houses a brain and may be homologous to the prostomium of other annelids.[15] The proboscis has rolled-in margins and a groove on the ventral surface. The distal end is sometimes forked. The proboscis can be very long; in the case of the Japanese species Ikeda taenioides, the proboscis can be 150 centimetres (59 in) long while the body is only 40 centimetres (16 in). Even smaller species like Bonellia can have a proboscis a metre (yard) long. The proboscis is used primarily for feeding. Respiration takes place through the proboscis and the body wall, with some larger species also using cloacal irrigation. In this process, water is pumped into and out of the rear end of the gut through the anus.[14][16]

Compared with other annelids, echiurans have relatively few setae (bristles). In most species, there are just two, located on the underside of the body just behind the proboscis, and often hooked. In others, such as Echiurus, there are also further setae near the posterior end of the animal. Unlike other annelids, adult echiurans have no trace of segmentation.[15] Most echiurans are a dull grey or brown but a few species are more brightly coloured, such as the translucent green Listriolobus pelodes.[17]

The body wall is muscular. It surrounds a large coelom which leads to a long looped intestine with an anus at the rear tip of the body.[18] The intestine is highly coiled, giving it a considerable length in relation to the size of the animal. A pair of simple or branched diverticula are connected to the rectum. These are lined with numerous minute ciliated funnels that open directly into the body cavity, and are presumed to be excretory organs.[15] The proboscis has a small coelomic cavity separated from the main coelom by a septum.[14]

Echiurans do not have a distinct respiratory system, absorbing oxygen through the body wall of both the trunk and proboscis, and through the cloaca in Urechis.[14] Although some species lack a blood vascular system, where it is present, it resembles that of other annelids. The blood is essentially colourless, although some haemoglobin-containing cells are present in the coelomic fluid of the main body cavity. There can be anywhere from one to over a hundred metanephridia for excreting nitrogenous waste, which typically open near the anterior end of the animal.[15] The nervous system consists of a brain near the base of the proboscis, and a ventral nerve cord running the length of the body. Aside from the absence of segmentation, this is a similar arrangement to that of other annelids. Echiurans do not have any eyes or other distinct sense organs,[15] but the proboscis is presumed to have a tactile sensory function.[17]

Distribution and habitat

Echiurans are exclusively marine and the majority of species live in the Atlantic Ocean. They are mostly infaunal, occupying burrows in the seabed, either in the lower intertidal zone or the shallow subtidal (e.g. the genera Echiurus, Urechis, and Ikeda).[17] Others live in holes in coral heads, and in rock crevices. Some are found in deep waters including at abyssal depths; in fact more than half the 70 species in Bonelliidae live below 3,000 m (10,000 ft).[14] They often congregate in sediments with high concentrations of organic matter. One species, Lissomyema mellita, which lives off the southeastern coast of the US, inhabits the tests (exoskeleton) of dead sand dollars. When the worm is very small, it enters the test and later becomes too large to leave.[19]

In the 1970s, the spoon worm Listriolobus pelodes was found on the continental shelf off Los Angeles in numbers of up to 1,500 per square metre (11 square feet) near sewage outlets.[20] The burrowing and feeding activities of these worms churned up and aerated the sediment and promoted a balanced ecosystem with a more diverse fauna than would otherwise have existed in this heavily polluted area.[20]

Behaviour

A spoon worm can move about on the surface by extending its proboscis and grasping some object before pulling its body forward. Some worms, such as Echiurus, can leave the substrate entirely, swimming by use of the proboscis and contractions of the body wall.[21]

Digging behaviour has been studied in Echiurus echiurus. When burrowing, the proboscis is raised and folded backwards and plays no part in the digging process. The front of the trunk is shaped into a wedge and pushed forward, with the two anterior chaetae (hooked chitinous bristles) being driven into the sediment. Next the rear end of the trunk is drawn forward and the posterior chaetae anchor it in place. These manoeuvres are repeated and the worm slowly digs its way forwards and downwards. It takes about forty minutes for the worm to disappear from view. The burrow descends diagonally and then flattens out, and it may be a metre or so long before ascending vertically to the surface.[22]

Spoon worms are typically detritivores, extending the flexible and mobile proboscis and gathering organic particles that are within reach. Some species can expand the proboscis by ten times its contracted length. The proboscis is moved by the action of cilia on the lower (ventral) surface "creeping" it forward. When food particles are encountered, the sides of the proboscis curl inward to form a ciliated channel.[14]

A worm such as Echiurus, living in the sediment, extends its proboscis from the rim of its burrow with the ventral side on the substrate. The surface of the proboscis is well equipped with mucus glands to which food particles adhere. The mucus is bundled into boluses by cilia and these are passed along the feeding groove by cilia to the mouth. The proboscis is periodically withdrawn into the burrow and later extended in another direction.[17]

Urechis, another tube-dweller, has a different method of feeding on detritus. It has a short proboscis and a ring of mucus glands at the front of its body. It expands its muscular body wall to deposit a ring of mucus on the burrow wall then retreats backwards, exuding mucus as it goes and spinning a mucus net. It then draws water through the burrow by peristaltic contractions and food particles stick to the net. When this is sufficiently clogged up, the spoon worm moves forward along its burrow devouring the net and the trapped particles. This process is then repeated and in a detritus-rich area may take only a few minutes to complete. Large particles are squeezed out of the net and eaten by other invertebrates living commensally in the burrow. These typically include a small crab, a scale worm and often a fish lurking just inside the back entrance.[17]

Ochetostoma erythrogrammon obtains its food by another method. it has two vertical burrows connected by a horizontal one. Stretching out its proboscis across the substrate it shovels material into its mouth before separating the edible particles. It can lengthen the proboscis dramatically while exploring new areas and periodically reverses its orientation in the burrow so as to use the back entrance to feed.[23] Other spoon worms live concealed in rock crevices, empty gastropod shells, sand dollar tests and similar places, extending their proboscises into the open water to feed.[18] Some are scavengers or detritivores, while others are interface grazers and some are suspension feeders.[24]

While the proboscis of a burrowing spoon worm is on the surface it is at risk of predation by bottom-feeding fish. In some species, the proboscis will autotomise (break off) if attacked and the worm will regenerate a proboscis over the course of a few weeks.[17] In a study in California, one of the most commonly found dietary items of the leopard shark was found to be the tube-dwelling innkeeper worm (Urechis caupo) which it extracted from the sediment by suction.[25]

Reproduction

Echiurans are dioecious, with separate male and female individuals. The gonads are associated with the peritoneal membrane lining the body cavity, into which they release the gametes. The sperm and eggs complete their maturation in the body cavity, before being stored in genital sacs, which are specialised metanephridia. At spawning time, the genital sacs contract and the gametes are squeezed into the water column through pores on the worm's ventral surface. Fertilization is external.[15]

Fertilized eggs hatch into free-swimming trochophore larvae. In some species, the larva briefly develops a segmented body before transforming into the adult body plan, supporting the theory that echiurans evolved from segmented ancestors resembling more typical annelids.[15]

The species Bonellia viridis, also remarkable for the possible antibiotic properties of bonellin, the green chemical in its skin, is unusual for its extreme sexual dimorphism. Females are typically 8 cm (3 in) in body length, excluding the proboscis, but the males are only 1 to 3 mm (0.04 to 0.12 in) long, and spend their adult lives within the uterus of the female.[15]

As food

Spoon worms are eaten in East and Southeast Asia. In South Korea fat innkeeper worms (Urechis unicinctus) are known as gaebul (개불). These worms are much prized and are often available at markets and stalls, chopped up and served raw in combination with raw sea cucumber, sea squirt and sea urchin, dressed with chili sauce and soy sauce.[26] They are also eaten as a fermented product known as gaebul-jeot.[27]

List of families

According to the World Register of Marine Species:[3]

- suborder Bonelliida[28]

- family Bonelliidae Lacaze-Duthiers, 1858

- family Ikedidae Bock, 1942

- suborder Echiurida[29]

- family Echiuridae Quatrefages, 1847

- family Thalassematidae Forbes & Goodsir, 1841

- family Urechidae Fisher & Macginitie, 1928

A worm of the family Bonelliidae

A worm of the family Bonelliidae Ochetostoma erythrogrammon, family Echiuridae

Ochetostoma erythrogrammon, family Echiuridae Arhynchite hayaoi, family Thalassematidae

Arhynchite hayaoi, family Thalassematidae Urechis unicinctus, family Urechidae

Urechis unicinctus, family Urechidae

References

- Jones, D.; Thompson, I. D. A. (1977). "Echiura from the Pennsylvanian Essex Fauna of northern Illinois". Lethaia. 10 (4): 317. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1977.tb00627.x.

- "Spoon Worm". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Tanaka, Masaatsu (2017). "Echiura". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Zhang, Z.-Q. (2011). "Animal biodiversity: An introduction to higher-level classification and taxonomic richness" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3148: 7–12.

- Tanaka, Masaatsu (2017). "Echiurus echiurus (Pallas, 1766)". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Banta, W.C.; Rice, M.E. (1970). "A restudy of the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale fossil worm, Ottoia prolifica" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Biology of the Sipunculata and Echiura. 11.

- Elsberry, Wesley R. (10 June 2006). "Phylum Echiura". Online Zoologists. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Dunn, C. W.; Hejnol, A.; Matus, D. Q.; Pang, K.; Browne, W. E.; Smith, S. A.; Seaver, E.; Rouse, G. W.; Obst, M.; Edgecombe, G. D.; Sørensen, M. V.; Haddock, S. H. D.; Schmidt-Rhaesa, A.; Okusu, A.; Kristensen, R. M. B.; Wheeler, W. C.; Martindale, M. Q.; Giribet, G. (2008). "Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life". Nature. 452 (7188): 745–749. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..745D. doi:10.1038/nature06614. PMID 18322464.

- Bourlat, S.; Nielsen, C.; Economou, A.; Telford, M. (2008). "Testing the new animal phylogeny: A phylum level molecular analysis of the animal kingdom". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 49 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.07.008. PMID 18692145.

- Struck, T. H.; Paul, C.; Hill, N.; Hartmann, S.; Hösel, C.; Kube, M.; Lieb, B.; Meyer, A.; Tiedemann, R.; Purschke, G. N.; Bleidorn, C. (2011). "Phylogenomic analyses unravel annelid evolution". Nature. 471 (7336): 95–98. Bibcode:2011Natur.471...95S. doi:10.1038/nature09864. PMID 21368831.

- Struck, T. H.; Schult, N.; Kusen, T.; Hickman, E.; Bleidorn, C.; McHugh, D.; Halanych, K. M. (2007). "Annelid phylogeny and the status of Sipuncula and Echiura". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 57. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-57. PMC 1855331. PMID 17411434.

- Tilic, Ekin; Lehrke, Janina; Bartolomaeus, Thomas; Colgan, Donald James (3 March 2015). "Homology and Evolution of the Chaetae in Echiura (Annelida)". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0120002. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120002. PMC 4348511. PMID 25734664.

- "Introduction to the Echiura". UC Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology, 7th edition. Cengage Learning. pp. 490–495. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

- Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 870–873. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- Toonen, Rob (2012). "Part 6: Phylum Sipuncula and Phylum Annelida". Reefkeeper's Guide to Invertebrate Zoology. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- Walls, Jerry G. (1982). Encyclopedia of Marine Invertebrates. TFH Publications. pp. 262–267. ISBN 0-86622-141-7.

- Felty Light, Sol (1954). Intertidal Invertebrates of the Central California Coast. Google Books. p. 108. ISBN 9780520007505. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Conn, H.W. (1886). "Life history of Thalassema mellita". Stud. Biol. Lab. Johns Hopkins Univ.: 1884–1887.

- Stull, Janet K.; Haydock, C.Irwin; Montagne, David E. (1986). "Effects of Listriolobus pelodes (Echiura) on coastal shelf benthic communities and sediments modified by a major California wastewater discharge". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 22 (1): 1–17. Bibcode:1986ECSS...22....1S. doi:10.1016/0272-7714(86)90020-X.

- "Echiuroidea". Encyclopædia Britannica 1911. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- Cowles, Dave (2005). "Echiurus echiurus subspecies alaskanus Fisher, 1946". Invertebrates of the Salish Sea. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- Chuang, S. H. (1962). "Feeding Mechanism of the Echiuroid, Ochetostoma erythrogrammon Leuckart & Rueppell, 1828". Biological Bulletin. 123 (1): 80–85. JSTOR 1539504.

- van der Land, Jacob (2004). "Echiuroidea". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Tallent, L.G. (1976). "Food habits of the leopard shark, Triakis semifasciata, in Elkhorn Slough, Monterey Bay, California". California Fish and Game. 62 (4): 286–298.

- Brown, Nicholas; Eddy, Steve (2015). Echinoderm Aquaculture. Wiley. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-119-00585-8.

- Kun-Young Park; Dae Young Kwon; Ki Won Lee; Sunmin Park (2018). Korean Functional Foods: Composition, Processing and Health Benefits. CRC Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-351-64369-6.

- Tanaka, Masaatsu (2017). "Bonelliida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Tanaka, Masaatsu (2017). "Echiurida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 9 March 2019.