Ebenezer Scrooge

Ebenezer Scrooge (/ˌɛbɪˈniːzər ˈskruːdʒ/) is the protagonist of Charles Dickens' 1843 novella, A Christmas Carol. At the beginning of the novella, Scrooge is a cold-hearted miser who despises Christmas. The tale of his redemption by three spirits (the Ghost of Christmas Past, the Ghost of Christmas Present, and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come) has become a defining tale of the Christmas holiday in the English-speaking world.

| Ebenezer Scrooge | |

|---|---|

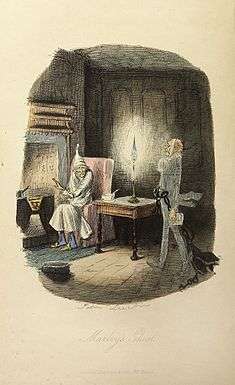

Ebenezer Scrooge encounters "Jacob Marley's ghost" in Dickens's novella, A Christmas Carol | |

| Created by | Charles Dickens |

| Portrayed by | See below |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Title | A Christmas Carol |

| Occupation | Businessman[lower-alpha 1] |

Dickens describes Scrooge thus early in the story: "The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice." Towards the end of the novella, Scrooge is transformed by the spirits into a better person who changed his ways to become more friendly and less miserly.

Scrooge's last name has come into the English language as a byword for stinginess and misanthropy, while his catchphrase, "Bah! Humbug!" is often used to express disgust with many modern Christmas traditions.

Description

Dickens describes Scrooge as "a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint,… secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster." He does business from a warehouse and is known among the merchants of the Royal Exchange as a man of good credit. Despite having considerable personal wealth, he underpays his clerk and hounds his debtors relentlessly, while living cheaply and joylessly in the chambers of his deceased business partner, Jacob Marley. Most of all he detests Christmas, which he associates with reckless spending. When two men approach him on Christmas Eve for a donation to charity, he sneers that the poor should avail themselves of the treadmill or the workhouses, or else die to reduce the surplus population.

Flashbacks of Scrooge's early life show that his unkind father placed him in a boarding school, where at Christmas-time he remained alone while his schoolmates traveled home. He then apprenticed at the warehouse of a jovial and generous master, Fezziwig. He proposed to a woman named Belle and dedicated himself to making enough money to rise out of poverty, but his fiancée was disgusted by his obsession with money and left him one Christmas, eventually marrying another man. The present-day Scrooge reacts to these memories with a mixture of nostalgia and deep regret.

After the three visiting spirits warn him that his current path brings hardship for others and shame for himself, Scrooge commits to being more generous. He accepts his nephew's invitation to Christmas dinner, provides for his clerk, and donates to the charity fund. In the end, he becomes known as the embodiment of the Christmas spirit.

Origins

Several theories have been put forward as to where Dickens got inspiration for the character.

- Ebenezer Scroggie, a merchant from Edinburgh who won a catering contract for King George IV's visit to Scotland. He was buried in Canongate Kirkyard, with a gravestone that is now lost. The theory is that Dickens noticed the gravestone that described Scroggie as being a "meal man" (corn merchant) but misread it as "mean man".[1][2] This theory has been described as "a probable Dickens hoax" for which "[n]o one could find any corroborating evidence".[3]

- It has been suggested that he chose the name Ebenezer ("stone (of) help") to reflect the help given to Scrooge to change his life.[4]

- One school of thought is that Dickens based Scrooge's views on the poor on those of demographer and political economist Thomas Malthus, as evidenced by his callous attitude towards the "surplus population".[5][6]

- Another is that the minor character Gabriel Grub from The Pickwick Papers was worked up into a more mature characterization (his name stemming from an infamous Dutch miser, Gabriel de Graaf).[7][8]

- Jemmy Wood, owner of the Gloucester Old Bank and possibly Britain's first millionaire, was nationally renowned for his stinginess, and may have been another.[9]

- The man whom Dickens eventually mentions in his letters[10] and who strongly resembles the character portrayed by Dickens's illustrator, John Leech, was a noted British eccentric and miser named John Elwes (1714–1789).

Kelly writes that Scrooge may have been influenced by Dickens's conflicting feelings for his father, whom he both loved and demonised. This psychological conflict may be responsible for the two radically different Scrooges in the tale—one a cold, stingy and greedy semi-recluse, the other a benevolent, sociable man.[11] Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, a professor of English literature, considers that in the opening part of the book covering young Scrooge's lonely and unhappy childhood, and his aspiration for money to avoid poverty "is something of a self-parody of Dickens's fears about himself"; the post-transformation parts of the book are how Dickens optimistically sees himself.[12]

Scrooge could also be based on two misers: the eccentric John Elwes, MP,[13] or Jemmy Wood, the owner of the Gloucester Old Bank who was also known as "The Gloucester Miser".[14] According to the sociologist Frank W. Elwell, Scrooge's views on the poor are a reflection of those of the demographer and political economist Thomas Malthus,[15] while the miser's questions "Are there no prisons? ... And the Union workhouses? ... The treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour, then?" are a reflection of a sarcastic question raised by the reactionary philosopher Thomas Carlyle, "Are there not treadmills, gibbets; even hospitals, poor-rates, New Poor-Law?"[16][lower-alpha 2]

There are literary precursors for Scrooge in Dickens's own works. Peter Ackroyd, Dickens's biographer, sees similarities between Scrooge and the elder Martin Chuzzlewit character, although the miser is "a more fantastic image" than the Chuzzlewit patriarch; Ackroyd observes that Chuzzlewit's transformation to a charitable figure is a parallel to that of the miser.[18] Douglas-Fairhurst sees that the minor character Gabriel Grub from The Pickwick Papers was also an influence when creating Scrooge.[19][lower-alpha 3]

Portrayals in notable adaptations

- Tom Ricketts in A Christmas Carol, 1908

- Marc McDermott in 1910

- Seymour Hicks in Scrooge 1913, and again in Scrooge, 1935

- Rupert Julian in 1916

- Russell Thorndike in 1923

- Bransby Williams in 1928 and 1936, 1950 on television

- Lionel Barrymore on radio 1934–1935, 1937, 1939–1953

- John Barrymore in 1936 on radio, for ailing brother Lionel

- Orson Welles in 1938 on radio replacing Lionel Barrymore for one appearance only.

- Reginald Owen in 1938

- Claude Rains in 1940 on radio

- Ronald Colman in 1941 on radio and again in 1949

- John Carradine in 1947 on radio and television

- Taylor Holmes in 1949

- Alastair Sim in 1951, and again in 1971 (voice)

- Fredric March in 1954

- Basil Rathbone in 1956 and 1958

- John McIntire in 1957

- Stan Freberg in Green Chri$tma$, 1958.

- Jim Backus (as Quincy Magoo) in Mister Magoo's Christmas Carol, 1962

- Cyril Ritchard in 1964

- Sterling Hayden as Daniel Grudge in Rod Serling's A Carol for Another Christmas (1964)

- Wilfrid Brambell in a 1966 radio musical version (adapted from his Broadway role)

- Sid James in the Carry On Christmas Specials, 1969

- Ron Haddrick in the animated TV film A Christmas Carol (1969) and again in the Australian animated film A Christmas Carol (1982)

- Albert Finney in 1970

- Marcel Marceau in 1973

- Michael Hordern in 1977

- Rich Little as W. C. Fields playing Scrooge in Rich Little's Christmas Carol, 1978

- Walter Matthau (voice) in The Stingiest Man in Town, 1978

- Henry Winkler as Benedict Slade in An American Christmas Carol, 1979

- Hoyt Axton as Cyrus Flint in Skinflint: A Country Christmas Carol, 1979

- Mel Blanc (as Yosemite Sam) in Bugs Bunny's Christmas Carol, 1979

- Henk Van Ulzen in De Wonderbaarlijke Genezing Van (the Wonderfull Cure of) Ebenezer Scrooge, 1979

- Hal Landon Jr. as Ebenezer Scrooge since 1980, more than 1,100 performances.

- Alan Young (as Scrooge McDuck) in Mickey's Christmas Carol, 1983

- George C. Scott in 1984

- Mel Blanc (this time as Cosmo Spacely) in The Jetsons episode "A Jetson Christmas Carol", 1985

- Robert Guillaume as John Grin in John Grin's Christmas, 1986

- Oliver Muirhead as "Constable Scrooge" in A Christmas Held Captive, 1986

- Bill Murray as Frank Cross in Scrooged, 1988

- Buddy Hackett (as himself) played Scrooge in the film-within-a-film.

- Rowan Atkinson as Ebenezer Blackadder in Blackadder's Christmas Carol, 1988

- Michael Caine in The Muppet Christmas Carol, 1992

- Jeffrey Sanzel has appeared in more than 1,000 stage performances since 1992.

- James Earl Jones in Bah, Humbug, 1994

- Walter Charles, Tony Randall, Terrence Mann, Hal Linden, Roddy McDowall, F. Murray Abraham, Frank Langella, Tony Roberts, Roger Daltrey, and Jim Dale in the stage version of Alan Menken's musical (1994–2003)

- Henry Corden (as Fred Flintstone) in A Flintstones Christmas Carol, 1994

- Susan Lucci as Elizabeth "Ebbie" Scrooge in Ebbie, 1995

- Cicely Tyson as Ebenita Scrooge in Ms. Scrooge, 1997

- Tim Curry (voice) in 1997; A Christmas Carol (the Theater at Madison Square Garden 2001 play)

- Ernest Borgnine (as Carface Carruthers) in An All Dogs Christmas Carol, 1998

- Jack Palance in 1998

- Patrick Stewart in 1999

- Vanessa Williams as Ebony Scrooge in A Diva's Christmas Carol, 2000

- Ross Kemp as Eddie Scrooge in 2000

- Adrienne Carter as Annie Redfeather as Annie Scrooge in Adventures from the Book of Virtues: Compassion Pt. 1 & 2, 2000

- Dean Jones in Scrooge and Marley, 2001

- Tori Spelling as "Scroogette" Carol Cartman in A Carol Christmas, 2003

- Phil Vischer (as Mr. Nezzer) in An Easter Carol, 2004

- Scrooge appears as a puppet in a minor role in the 2004 film The Polar Express, in which he confronts "the boy", making him flee back into the seating area of the train.

- Kelsey Grammer in 2004

- Joe Alaskey (as Daffy Duck) in Bah, Humduck! A Looney Tunes Christmas, 2006

- Helen Fraser as Sylvia Hollamby in Bad Girls 2006 Christmas Special

- John Burnside in Hot Rod, 2007

- Morwenna Banks as Eden Starling (Barbie) in Barbie in A Christmas Carol, 2008

- Jim Carrey in 2009 (Carrey also played the three spirits haunting Scrooge).[21]

- Catherine Tate as Nan in Nan's Christmas Carol, 2009

- Matthew McConaughey as Connor "Dutch" Mead in Ghosts of Girlfriends Past, 2009

- Christina Milian as Sloane Spencer in Christmas Cupid, December 2010

- Eric Braeden as Victor Newman in "Victor's Christmas Carol" on The Young and the Restless, December 2010

- Michael Gambon as Kazran Sardick in "A Christmas Carol" on Doctor Who, December 2010[22][23]

- George Lopez as Grouchy Smurf in The Smurfs: A Christmas Carol, 2011

- Emmanuelle Vaugier as Carol Huffman in the 2012 TV film It's Christmas, Carol!

- Robert Powell in Neil Brand's 2014 BBC Radio 4 adaptation of A Christmas Carol.[24]

- Ned Dennehy in the BBC drama Dickensian, 2015

- Jason Graae in the musical Scrooge in Love!, 2016[25]

- Kelly Sheridan as Starlight Glimmer (playing Snowfall Frost) in the My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic episode "A Hearth's Warming Tail", 2016

- Christopher Plummer in The Man Who Invented Christmas, 2017

- Roger L. Jackson as Mojo Jojo in The Powerpuff Girls "You're A Good Man, Mojo Jojo!", 2017

- Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin in Family Guy, "Don't Be a Dickens at Christmas", 2017

- Kate Micucci as Velma Dinkley in Be Cool, Scooby-Doo! episode "Scroogey Doo", 2017

- Stuart Brennan in 2018[26]

- Guy Pearce in the BBC/FX miniseries, 2019

See also

Notes

- Scrooge's type of business is not stated in the original work. He is said to operate from a warehouse, having apprenticed in another. At least part of his business consists in exchanging money obligations and collecting debts. Several adaptations have depicted him as a money-lender.

- Carlyle's original question was written in his 1840 work Chartism.[17]

- Grub's name came from a 19th century Dutch miser, Gabriel de Graaf, a morose gravedigger.[20]

Citations

- "Revealed: the Scot who inspired Dickens' Scrooge". The Scotsman. 24 December 2004. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

Details of Scroggie’s life are sparse, but he was a vintner as well as a corn merchant.

- "BBC Arts - That Ebenezer geezer... who was the real Scrooge?". BBC. Retrieved 2016-04-30.

- "Mr Punch is still knocking them dead after 350 years". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- Kincaid, Cheryl Anne. Hearing the Gospel through Charles Dickens's "A Christmas Carol" (2 ed.). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 7–8. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Frank W. Elwell, Reclaiming Malthus, 2 November 2001, accessed 30 August 2013.

- Nasar, Sylvia (2011). Grand pursuit : the story of economic genius (1st Simon & Schuster hardcover ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 3–10. ISBN 978-0-684-87298-8.

- "Real-life Scrooge was Dutch gravedigger", 25 December 2007, archived from the original 27 December 2007.

- "Fake Scrooge 'was Dutch gravedigger'", 26 December 2007, archived from the original 6 December 2008.

- Silence, Rebecca (2015). Gloucester History Tour. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 40.

- The Letters of Charles Dickens by Charles Dickens, Madeline House, Graham Storey, Margaret Brown, Kathleen Tillotson, & The British Academy (1999) Oxford University Press [Letter to George Holsworth, 18 January 1865] pp.7.

- Kelly 2003, p. 14.

- Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xix.

- Gordon 2008; DeVito 2014, 424.

- Jordan 2015, Chapter 5; Sillence 2015, p. 40.

- Elwell 2001; DeVito 2014, 645.

- Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xiii.

- Carlyle 1840, p. 32.

- Ackroyd 1990, p. 409.

- Douglas-Fairhurst 2006, p. xviii; Alleyne 2007.

- Alleyne 2007.

- Fleming, Michael. "Jim Carrey set for 'Christmas Carol': Zemeckis directing Dickens adaptation", Variety, 2007-07-06. Retrieved on 2007-09-11.

- "Doctor Who Christmas Special – A Christmas Carol". Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- "Christmas Day". Radio Times. 347 (4520): 174. December 2010.

- "BBC Radio 4 - Saturday Drama, A Christmas Carol". BBC.

- Heymont, George (29 January 2016). "Rule Britannia!". Huffington Post. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- "From Charles Dickens to Michael Caine, here are the five best Scrooges". The Independent. December 19, 2018.

References

- Ackroyd, Peter (1990). Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 978-1-85619-000-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alleyne, Richard (24 December 2007). "Real Scrooge 'was Dutch gravedigger'". The Daily Telegraph.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carlyle, Thomas (1840). Chartism. London: J. Fraser. OCLC 247585901.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DeVito, Carlo (2014). Inventing Scrooge (Kindle ed.). Kennebunkport, ME: Cider Mill Press. ISBN 978-1-60433-555-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dickens, Charles (1843). A Christmas Carol. London: Chapman and Hall. OCLC 181675592.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert (2006). "Introduction". In Dickens, Charles (ed.). A Christmas Carol and other Christmas Books. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–xxix. ISBN 978-0-19-920474-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elwell, Frank W. (2 November 2001). "Reclaiming Malthus". Rogers State University. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gordon, Alexander (2008). "Elwes, John (1714–1789)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8776. Retrieved 13 January 2016. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Jordan, John O. (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66964-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kelly, Richard Michael (2003). "Introduction". In Dickens, Charles (ed.). A Christmas Carol. Ontario: Broadway Press. pp. 9–30. ISBN 978-1-55111-476-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sillence, Rebecca (2015). Gloucester History Tour. Stroud, Glos: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-4859-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)