East Prigorodny Conflict

The East Prigorodny Conflict, also referred to as the Ossetian–Ingush Conflict, was an inter-ethnic conflict in the eastern part of the Prigorodny district in the Republic of North Ossetia – Alania, which started in 1989 and developed, in 1992, into a brief ethnic war between local Ingush and Ossetian paramilitary forces.[3]

| East Prigorodny Conflict | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Post-Soviet conflicts | |||||||

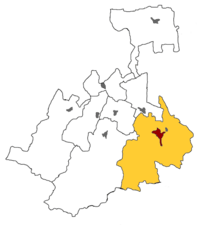

Map of the Prigorodny district inside North Ossetia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

and security forces 9th Motor Rifle Division 76th Guards Air Assault Division |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

192 dead[2] 379 wounded[2] |

350 dead[3] 457 wounded[4] | ||||||

|

30,000–60,000 Ingush refugees[5] 9,000 Ossetian refugees[3] | |||||||

Origins of the conflict

The present conflict emerges from the policies of both Imperial and Soviet governments, which exploited ethnic differences to further their own ends, namely the perpetuation of central rule and authority. Tsarist policy in the North Caucasus generally favored Ossetians, who inhabited an area astride the strategically important Georgian Military Highway, a key link between Russia proper and her Transcaucasian colonies. In addition, the Ossetians were one of the few friendly peoples in a region that for much of the nineteenth century bitterly resisted Russian rule; a majority of Ossetians shared the same Eastern Orthodox Christian faith with Russians (while a minority are Sunni Muslim), while the majority of the other ethnic groups of the North Caucasus were Muslim. Russian authorities also conducted population transfers of native people in the area at will and brought in large numbers of Terek Cossacks. Under the Soviets, local Cossacks (many of the early members of the Terek Cossacks were Ossetians[6]) were punished for their support of anti-Soviet White forces during the Russian Civil War (1918–1921) and banished from the area, including from the Prigorodnyi region which was given to the Ingush, ostensibly for their support of the Red or Bolshevik forces during the conflict. Soviet administrators often arbitrarily created territorial units in the North Caucasus, thereby enhancing differences by splitting apart like peoples or fostering dependence by uniting different groups. In January 1920, the Autonomous Mountain Soviet Socialist Republic, referred to as the "Mountaineers Republic," was formed, with its capital in Vladikavkaz. Initially, the "Mountaineers Republic," included the Kabards, Chechens, Ingush, Ossetians, Karachai, Cherkess, and Balkars, but it quickly began to disintegrate and new territorial units were created. In 1924, the Ingush were given their own territorial unit that included the Prigorodnyi region. In 1934, the Ingush were merged territorially with the Chechens; in 1936 this territory was formed into the Checheno-Ingush ASSR with its capital in Grozny. The Prigorodnyi region still remained within the Chechen–Ingush entity.[3][7]

In 1944, near the end of World War II, the Ingush and the Chechen peoples were accused of collaborating with the Nazis, and by order of Joseph Stalin, the whole population of Ingush and Chechens were deported to Central Asia and Siberia. Soon after, the depopulated Prigorodny district was transferred to North Ossetia.[8]

In 1957, the repressed Ingush and Chechens were allowed to return to their native land and the Checheno-Ingush Republic was restored, with the Prigorodny district maintained as part of North Ossetia. Soviet authorities attempted to prevent Ingush from returning to their territory in Prigorodny district; however, Ingush families managed to move in, purchase houses back from the Ossetians and resettled the district in greater numbers.[8] This gave rise to the idea of "restoring historical justice" and "returning native lands", among the Ingush population and intelligence, which contributed to the already existing tensions between ethnic Ossetians and Ingush. Between 1973 and 1980 the Ingush voiced their demands for the reunification of the Prigorodny district with Ingushetia by staging various protests and meetings in Grozny.

The tensions increased in early 1991, during the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the Ingush openly declared their rights to the Prigorodny district according to the Soviet law adopted by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on April 26, 1991; in particular, the third and the sixth article on "territorial rehabilitation." The law gave the Ingush legal grounds for their demands, which caused serious turbulence in a region in which many people had free access to weapons, resulting in an armed conflict between ethnic Ingush population of the Prigorodny district and Ossetian armed militias from Vladikavkaz.[9]

Armed conflict

Ethnic violence rose steadily in the area of the Prigorodny district, to the east of the Terek River, despite the introduction of 1,500 Soviet Internal Troops to the area.

During the summer and early autumn of 1992, there was a steady increase in the militancy of Ingush nationalists. At the same time, there was a steady increase in incidents of organized harassment, kidnapping and rape against Ingush inhabitants of North Ossetia by their Ossetian neighbours, police, security forces and militia.[3] Ingush fighters marched to take control over Prigorodny District and on the night of October 30, 1992, open warfare broke out, which lasted for a week. The first people killed were respectively Ossetian and Ingush militsiya staff (as they had basic weapons). While Ingush militias were fighting the Ossetians in the district and on the outskirts of the North Ossetian capital Vladikavkaz, Ingush from elsewhere in North Ossetia were forcibly evicted and expelled from their homes. Russian OMON forces actively participated in the fighting and sometimes led Ossetian fighters into battle.[3]

On October 31, 1992, armed clashes broke out between Ingush militias and North Ossetian security forces and paramilitaries supported by Russian Interior Ministry (MVD) and Army troops in the Prigorodny District of North Ossetia. Although Russian troops often intervened to prevent some acts of violence by Ossetian police and republican guards, the stance of the Russian peacekeeping forces was strongly pro-Ossetian,[8] not only objectively as a result of its deployment, but subjectively as well. The fighting, which lasted six days, had at its root a dispute between ethnic Ingush and Ossetians over the Prigorodnyi region, a sliver of land of about 978 square kilometers over which both sides lay claim. That dispute has not been resolved, nor has the conflict. Both sides have committed human rights violations. Thousands of homes have been wantonly destroyed, most of them Ingush. More than one thousand hostages were taken on both sides, and as of this writing approximately 260 individuals-mostly Ingush-remain unaccounted for, according to the Procuracy of the Russian Federation. Nearly five hundred individuals were killed in the first six days of conflict. Hostage-taking, shootings, and attacks on life and property continue to this day[10]. President Boris Yeltsin issued a decree that the Prigorodny district was to remain part of North Ossetia on November 2.

Casualties

Total dead as of June 30, 1994: 644.[11]

| Ossetian | 151 |

| Ingush | 302 |

| Other Nationalities | 25 |

| North Ossetian Ministry of the Interior | 9 |

| Russian Ministry of Defense | 8 |

| Russian Ministry of the Interior, Internal Troops | 3 |

| Ossetian | 9 |

| Ingush | 3 |

| Other Nationalities | 2 |

| Unknown Nationalities | 12 |

| Unified Investigative Group, Ministry of the Interior | 1 |

| Ossetian | 40 |

| Ingush | 333 |

| Other nationalities | 21 |

| Unknown nationalities | 30 |

| North Ossetian Ministry of the Interior | 9 |

| Ingush Ministry of the Interior | 5 |

| Russian Ministry of Defense | 3 |

| Russian Ministry of the Interior, Internal Troops | 4 |

| Unified Investigative Group, Russian Ministry of the Interior | 8 |

| Ossetian | 6 |

| Ingush | 3 |

| Other nationalities | 7 |

| Russian Ministry of Defense | 1 |

| Russian Ministry of the Interior, Internal Troops | 2 |

| Unified Investigative Group, Russian Ministry of the Interior | 4 |

Allegations of ethnic cleansing

Human Rights Watch/Helsinki takes no position on the ultimate status of the Prigorodnyi region. HRW's report says:

"Human Rights Watch/Helsinki thanks both North Ossetian and Ingush authorities as well as officials from the Russian Temporary Administration (now the Temporary State Committee) for their cooperation with the mission participants. Human Rights Watch/Helsinki would like to express our appreciation to all those who read the report and commented on it, including Prof. John Collarusso of McMaster University. We would also like to thank the members of the Russian human rights group Memorial, who provided generous assistance and advice. In 1994 Memorial published an excellent report on the conflict in the Prigorodnyi region, "Two Years after the War: The Problem of the Forcibly Displaced in the Area of the Ossetian–Ingush Conflict." Finally, we would like to thank the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Henry Jackson Fund, the Merck Fund and the Moriah Fund for their support. Human Rights Watch/Helsinki takes no position on the ultimate status of the Prigorodnyi region. Our sole concern is conformance with international humanitarian law."[3][7]

During the three years preceding the outbreak of conflict in October 1992, both the Ingush and the Ossetians armed at a furious pace. Much of the North Ossetian ASSR's acquisition of weapons was connected with the war in South Ossetia. Weapons flowed into Ingushetiya freely from Chechnya, and until the outbreak of the conflict one could purchase automatic weapons freely at the market in Nazran.[3][7]

During the first period of the conflict, North Ossetian Interior Ministry troops and paramilitaries, South Ossetian armed groups, and Ingush militants took hostages, committed murder, looted, wantonly destroyed civilian property, and used indiscriminate fire.[3][7]

During the second period, a majority of Ingush homes in the Prigorodnyi region were looted by North Ossetian paramilitaries and South Ossetian armed groups again with – at the very least – the acquiescence of North Ossetian and Russian security authorities. Most of this destruction occurred in the second two weeks of November 1992 and early December in spite of the fact that a state of emergency had been proclaimed in November 2, 1992, and the Prigorodnyi region was largely under the control of Russian and North Ossetian forces by November 5, 1992, after the Ingush had fled or been expelled. The state of emergency was annulled in February 1995. As a result of the conflict, a total of 2,728 Ingush and 848 Ossetian homes as well as numerous schools, shops, restaurants, and various parts of the infrastructure were destroyed. Half of the destroyed Ossetian homes have been fully repaired.[3][7]

Parties to the Ingush–Ossetian conflict are bound by international humanitarian law as it applies to the Russian Federation. The Russian Federation and subordinate state authorities are further bound by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to which Russia is a party. All parties to the conflict have committed abuses that constitute violations of both branches of international law; most such abuses are also punishable as offenses under Russian criminal law as well.[3][7]

The fighting was the first armed conflict on Russian territory after the collapse of the Soviet Union. When it ended after the deployment of Russian troops, most of the estimated 34,500–64,000 Ingush residing in the Prigorodnyi region and North Ossetia as a whole had been forcibly displaced by Ossetian forces, often supported by Russian troops. There are no authoritative figures for the number of Ingush forcibly evicted from the Prigorodnyi region and other parts of North Ossetia, because there were no accurate figures for the total pre-1992 Ingush population of Prigorodnyi and North Ossetia. Ingush often lived there illegally and thus were not counted by a census. Thus the Russian Federal Migration Service counts 46,000 forcibly displaced from North Ossetia, while the Territorial Migration Service of Ingushetiya puts the number at 64,000. According to the 1989 census 32,783 Ingush lived in the North Ossetian ASSR; three years later the passport service of the republic put the number at 34,500. According to the migration service of North Ossetia, about 9,000 Ossetians were forced to flee the Prigorodnyi region and seek temporary shelter elsewhere; the majority have returned.[3][7]

The pressure from Moscow and the Russian-mediated Ossetian–Ingush agreement of 1995 induced the North Ossetian authorities to allow Ingush refugees from four settlements in the Prigorodny district to return to their homes. The return of most refugees had been blocked by the local government and only the Ossetians had been able to return since. Meanwhile, the former Ingush homes and settlements in the district have been gradually occupied by the Ossetian refugees from Georgia.

It is estimated that between 1994 and 2008, around 25,000 of the Ingush people returned to Prigorodny District while some 7,500 remained in Ingushetia.[12]

On October 11, 2002, the presidents of Ingushetia and North Ossetia signed an agreement "promoting cooperation and neighborly relations," in which Ingush refugees and human rights advocates invested much hope. However, the Beslan hostage crisis of 2004 hampered the return process and worsened Ossetian–Ingush relations.

See also

References

- "The Localized Geopolitics of Displacement and Return in Eastern Prigorodnyy Rayon, North Ossetia" (PDF). colorado.edu. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- Осетино‑ингушский конфликт: хроника событий (in Russian). Inca Group "War and Peace". November 8, 2008.

- Russia: The Ingush–Ossetian Conflict in the Prigorodnyi Region (Paperback) by Human Rights Watch Helsinki Human Rights Watch (April 1996) ISBN 1-56432-165-7

- Prague Watchdog Report, published July 28, 2006

- http://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/secret-history-beslan

- Wixman. The Peoples of the USSR. p. 52

- "Russia". hrw.org. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- A. Dzadziev. The Ingush–Ossetian conflict: The Roots and the Present Day // Journal of Social and Political Studies. 2003, _ 6 (24)

- The Ossetian–Ingush Conflict: Perspectives of Getting out of Deadlock Moscow. Russian Independent Institute of Social and National Problems, Professional Sociological Assiciation. ROSSPEN. 1998. p.30

- https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/1996/Russia.htm

- Raion Chrezvychainogo Polozheniya (Severnaya Osetiya I Ingushetiya), (The Region of Emergency Rule: North Ossetia and Ingushetiya,) Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia, 1994, p. 63. This compilation of reports, statistics, and documents is published by the Temporary Administration.

- https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/28000/eur460102011en.pdf