World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations

The World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations is a working party (WP.29)[1] of the Sustainable Transport Division of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Its responsibility is to manage the multilateral Agreements signed in 1958, 1997 and 1998 concerning the technical prescriptions for the construction, approval of wheeled vehicles as well as their Periodic Technical Inspection and, to operate within the framework of these three Agreements to develop and amend UN Regulations, UN Global Technical Regulations and UN Rules.

| |

| Abbreviation | WP.29 |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1952 |

| Type | Working Party |

| Legal status | Active |

Head | |

Parent organization | UNECE Inland Transport Committee |

| Website | UNECE Transport - WP29 |

WP.29 was established in June 1952 as the "Working Party of experts on technical requirement of vehicles", while its current name was adopted in 2000.

At its inception, WP.29 had a broader european scope. Since 2000, the global scope of this forum was recognized given the active participation of Countries in all continents.

The forum works on regulations covering vehicle safety, environmental protection, energy efficiency and theft-resistance.

This work affects de facto vehicle design and facilitates international trade.

1958 Agreement

The core of the Forum's work is based around the "1958 Agreement", formally titled "Agreement concerning the adoption of uniform technical prescriptions for wheeled vehicles, equipment and parts which can be fitted and/or be used on wheeled vehicles and the conditions for reciprocal recognition of approvals granted on the basis of these prescriptions" (E/ECE/TRANS/505/Rev.2, amended on 16 October 1995). This forms a legal framework wherein participating countries (contracting parties) agree on a common set of technical prescriptions and protocols for type approval of vehicles and components. These were formerly called "UNECE Regulations" or, less formally, "ECE Regulations" in reference to the Economic Commission for Europe. However, since many non-European countries are now contracting parties to the 1958 Agreement, the regulations are officially entitled "UN Regulations".[2][3] According to the mutual recognition principle set in the Agreement, each Contracting Party's Type Approvals are recognised by all other Contracting Parties.

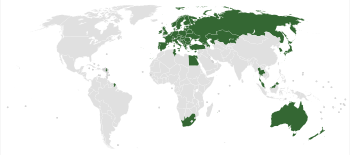

Participating countries

The first signatories to the 1958 Agreement include Italy (March 28), Netherlands (March 30), Germany (June 19), France (June 26), Hungary (June 30), Sweden and Belgium. Originally, the agreement allowed participation of ECE member countries only, but in 1995 the agreement was revised to allow non-ECE members to participate. Current participants include European Union and its member countries, as well non-EU UNECE members such as Norway, Russia, Ukraine, Croatia, Serbia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Azerbaijan and Tunisia, and even remote territories such as South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, Thailand and Malaysia.

As of 2016, the participants to the 1958 Agreement, with their UN country code, were:.[4]

| UN Code | Country | Effective date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28 January 1965 | ||

| 2 | 20 June 1959 | ||

| 3 | 26 April 1963 | ||

| 4 | 29 August 1960 | ||

| 5 | 20 June 1959 | ||

| 6 | 5 September 1959 | ||

| 7 | 2 July 1960 | ||

| 8 | 1 January 1993 | (formerly Czechoslovakia) | |

| 9 | 10 October 1961 | ||

| 10 | 12 March 2001 | (formerly Yugoslavia) | |

| 11 | 16 March 1963 | ||

| 12 | 11 May 1971 | ||

| 13 | 12 December 1971 | ||

| 14 | 28 August 1973 | ||

| 15 | (expired in 1999) | ||

| 16 | 4 April 1975 | ||

| 17 | 17 September 1976 | ||

| 18 | 20 December 1976 | ||

| 19 | 21 February 1977 | ||

| 20 | 13 March 1979 | ||

| 21 | 28 March 1980 | ||

| 22 | 17 February 1987 | ||

| 23 | 5 December 1992 | ||

| 24 | 24 March 1998 | ||

| 25 | 8 October 1991 | ||

| 26 | 25 June 1991 | ||

| 27 | 1 January 1993 | ||

| 28 | 2 July 1995 | ||

| 29 | 1 May 1995 | ||

| 31 | 6 March 1992 | ||

| 32 | 18 January 1999 | ||

| 34 | 21 January 2000 | ||

| 35 | 8 January 2011 | ||

| 36 | 29 March 2002 | ||

| 37 | 27 February 1996 | ||

| 39 | 14 June 2002 | ||

| 40 | 17 November 1991 | ||

| 42 | 24 March 1998 | ||

| 43 | 24 November 1998 | ||

| 45 | 25 April 2000 | ||

| 46 | 30 June 2000 | ||

| 47 | 17 June 2001 | ||

| 48 | 26 January 2002 | ||

| 49 | 1 May 2004 | ||

| 50 | 1 May 2004 | ||

| 51 | 31 December 2004 | ||

| 52 | 4 April 2006 | ||

| 53 | 1 May 2006 | ||

| 54 | 5 November 2011 | ||

| 56 | 3 June 2006 | ||

| 57 | 26 January 2016 | ||

| 58 | 1 January 2008 | ||

| 60 | 25 May 2015 | ||

| 62 | 3 February 2013 |

Most countries, even if not formally participating in the 1958 agreement, recognise the UN Regulations and either mirror the UN Regulations' content in their own national requirements, or permit the import, registration, and use of UN type-approved vehicles, or both. The United States and Canada (apart from Lighting Regulations) are the two significant exceptions; the UN Regulations are generally not recognised and UN-compliant vehicles and equipment are not authorised for import, sale, or use in the two regions, unless they are tested to be compliant with the region's car safety laws, or for limited non driving use (e.g. car show displays).[5]

Type approval

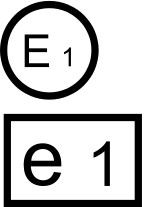

The 1958 Agreement operates on the principles of type approval and reciprocal recognition. Any country that accedes to the 1958 Agreement has authority to test and approve any manufacturer's design of a regulated product, regardless of the country in which that component was produced. Each individual design from each individual manufacturer is counted as one individual type. Once any acceding country grants a type approval, every other acceding country is obliged to honor that type approval and regard that vehicle or item of motor vehicle equipment as legal for import, sale and use. Items type-approved according to a UN Regulation are marked with an E and a number, within a circle. The number indicates which country approved the item, and other surrounding letters and digits indicate the precise version of the regulation met and the type approval number, respectively.

Although all countries' type approvals are legally equivalent, there are real and perceived differences in the rigour with which the regulations and protocols are applied by different national type approval authorities. Some countries have their own national standards for granting type approvals, which may be more stringent than called for by the UN regulations themselves. Within the auto parts industry, a German (E1) type approval, for example, is regarded as a measure of insurance against suspicion of poor quality or an undeserved type approval.[6]

UN Regulations

As of 2015, there are 135 UN Regulations appended to the 1958 Agreement; most regulations cover a single vehicle component or technology. A partial list of current regulations applying to passenger cars follows (different regulations may apply to heavy vehicles, motorcycles, etc.)

General lighting

- R3 — Retroreflecting devices

- R4 — Illumination of rear registration plates

- R6 — Direction indicators

- R7 — Front and rear position lamps, stop lamps and end-outline marker lamps

- R19 — Front fog lamps

- R23 — Reversing lights

- R37 — Filament lamps (bulbs) (See: Automotive lamp types)

- R38 — Rear fog lamps

- R48 — Installation of lighting and light-signalling devices

- R77 — Parking lamps

- R87 — Daytime running lamps

- R91 — Side marker lamps

- R112 — Headlamp Asymmetric

- R119 — Cornering lamps

- R123 — AFS lamps

- R128 — LED light sources

Headlamps

- R1 — Headlamps emitting an asymmetrical passing beam and/or a driving beam, equipped with R2 or HS1 bulbs (superseded by R112, but still valid for existing approvals)

- R5 — Sealed Beam headlamps emitting an asymmetrical passing beam and/or a driving beam

- R8 — Headlamps equipped with replaceable single-filament tungsten-halogen bulbs (superseded by R112, but still valid for existing approvals)

- R20 — Headlamps emitting an asymmetrical passing beam and/or a driving beam and equipped with halogen double-filament H4 bulbs (superseded by R112, but still valid for existing approvals)

- R31 — Halogen sealed beam headlamps emitting an asymmetrical passing beam and/or a driving beam

- R45 — Headlamp cleaners

- R98 — Headlamps equipped with gas-discharge light sources

- R99 — Gas-discharge light sources for use in approved gas-discharge lamp units of power-driven vehicles (See: Automotive lamp types)

- R112 — Headlamps emitting an asymmetrical passing beam and/or a driving beam and equipped with filament bulbs

- R113 — Headlamps emitting a symmetrical passing beam and/or a driving beam and equipped with filament bulbs

Instrumentation/controls

- R35 — arrangement of foot controls

- R39 — speedometer equipment

- R46 — rear-view mirrors

- R79 — steering equipment

Crashworthiness

- R11 — door latches and door retention components

- R13-H — braking (passenger cars)

- R13 — braking (trucks and busses)

- R14 — safety belt anchorages

- R16 — safety belts and restraint systems

- R17 — seats, seat anchorages, head restraints

- R27 — advance-warning triangles

- R42 — front and rear protective devices (bumpers, etc.)

- R43 — safety glazing materials and their installation on vehicles

- R94 — protection of the occupants in the event of a frontal collision

- R95 — protection of the occupants in the event of a lateral collision

- R116 — protection of motor vehicles against unauthorized use

- R129 — enhanced child restraint systems (ECRS)

Environmental compatibility

- R10 — electromagnetic compatibility

- R15 — emissions and fuel consumption (superseded by R83, R84 and R101)

- R24 — engine power measurement, smoke emissions, engine type approval

- R51 — noise emissions

- R68 — measurement of the maximum speed

- R83 — emission of pollutants according to engine fuel requirements

- R84 — measurement of fuel consumption

- R85 — electric drive trains — measurement of the net power and the maximum 30 minutes power of electric drive trains

- R100 — approval of battery electric vehicles with regard to specific requirements for the construction, Functional Safety and hydrogen emission.[7]

- R101 — measurement of the emission of carbon dioxide and fuel consumption

- R117 — rolling sound emissions of tyres

Tyres & wheels

- R30 — Tyres for passenger cars and their trailers

- R54 — Tyres for commercial vehicles and their trailers

- R64 — Temporary use spare unit, run flat tyres, run flat-system and tyre pressure monitoring

- R75 — Tyres for motorcycles/mopeds

- R88 — Retroreflective tyres for two-wheeled vehicles

- R106 — Tyres for agricultural vehicles

- R108 — Retreaded tyres for passenger cars and their trailers

- R109 — Retreaded tyres for commercial vehicles and their trailers

- R124 — Replacement wheels for passenger cars

Automated/autonomous vehicle regulations

- R157 — Automated Lane Keeping Systems

North America

The most notable non-signatory to the 1958 Agreement is the United States, which has its own Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards and does not recognise UN type approvals. However, both the United States and Canada are parties to the 1998 Agreement. UN-specification vehicles and components which do not also comply with the US regulations therefore cannot be imported to the US without extensive modifications. Canada has its own Canada Motor Vehicle Safety Standards, broadly similar to the US FMVSS, but Canada does also accept UN-compliant headlamps and bumpers. The impending Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between Canada and the European Union could see Canada recognise more UN Regulations as acceptable alternatives to the Canadian regulations.[8] Canada currently applies 14 of the 17 ECE main standards as allowable alternatives - the exceptions at this point relate to motorcycle controls and displays, motorcycle mirrors, and electronic stability control for passenger cars. These three remaining groups will be allowed in Canada by the time the ratification of the trade deal occurs.

Self-certification

Rather than a UN-style system of type approvals, the US and Canadian auto safety regulations operate on the principle of self-certification, wherein the manufacturer or importer of a vehicle or item of motor vehicle equipment certifies—i.e., asserts and promises—that the vehicle or equipment complies with all applicable federal or Canada Motor Vehicle Safety, bumper and antitheft standards.[9] No prior verification is required by a governmental agency or authorised testing entity before the vehicle or equipment can be imported, sold, or used. If reason develops to believe the certification was false or improper — i.e., that the vehicle or equipment does not in fact comply — then authorities may conduct tests and, if a noncompliance is found, order a recall and/or other corrective and/or punitive measures. Vehicle and equipment makers are permitted to appeal such penalties, but this is a difficult direction.[10] Non-compliances found that are arguably without effect to highway safety may be petitioned to skip recall (remedy and notification) requirements for vehicles already produced.[11]

Regulatory differences

Historically, one of the most conspicuous differences between UN and US regulations was the design and performance of headlamps. The Citroën DS shown here illustrates the large differences in headlamps during the 1940-1983 era when US regulations required sealed beam headlamps, which were prohibited in many European countries. A similar approach was evident with the US mandatory side marker lights.[12][13]

It is not currently possible to produce a single car design that fully meets both UN and US requirements,[14] but it is growing easier as technology, and both sets of regulations, evolve. Given the size of the US vehicle market, and differing marketing strategies in North America as opposed to the rest of the world, many manufacturers produce vehicles in four versions: North American, UNECE right-hand drive (RHD), UNECE left-hand-drive (LHD), and Rest of the World (for non-regulated countries or countries with poor market fuel quality.[14]

1998 Agreement

The "Agreement concerning the Establishing of Global Technical Regulations for Wheeled Vehicles, Equipment and Parts which can be fitted and/or be used on Wheeled Vehicles", or 1998 Agreement, is a subsequent agreement. Following its mission to harmonize vehicle regulations, the UNECE solved the main issues (Administrative Provisions for Type approval opposed to self-certification and mutual recognition of Type Approvals) preventing non-signatory Countries to the 1958 Agreement to fully participate to its activities.

The 1998 Agreement is born to produce meta regulations called Global Technical Regulations without administrative procedures for type approval and so, without the principle of mutual recognition of Type Approvals. The 1998 Agreement stipulates that Contracting Parties will establish, by consensus vote, United Nations Global Technical Regulations (UN GTRs) in a UN Global Registry. The UN GTRs contain globally harmonized performance requirements and test procedures. Each UN GTR contains extensive notes on its development. The text includes a record of the technical rationale, the research sources used, cost and benefit considerations, and references to data consulted. The Contracting Parties use their nationally established rulemaking processes when transposing UN GTRs into their national legislation. The 1998 Agreement currently has 33 Contracting Parties and 14 UN GTRs that have been established into the UN Global Registry.[15] Manufacturers and suppliers cannot use directly the UN GTRs as these are intended to serve the Countries and require transposition in national or regional law.

2013 Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (proposed)

As part of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations, the issues of divergent standards in automobile regulatory structure are being investigated. TTIP negotiators are seeking to identify ways to narrow the regulatory differences, potentially reducing costs and spurring additional trade in vehicles.[9]

OICA

Organisation Internationale des Constructeurs d'Automobiles (OICA) hosts on its web site the working documents from various United Nations expert groups including World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations.[16]

See also

- Worldwide harmonized Light vehicles Test Procedures

- Vehicle regulation

- Car safety

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

- Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards

- Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 108

- Automotive lighting

- Headlamps

- Assured clear distance ahead

References

- "Transport - Transport - UNECE" (PDF). www.unece.org.

- "WP.29 - Introduction - Transport - UNECE". www.unece.org.

- The End of the 'ECE' Era, Driving Vision News, 29 August 2011

- "Status of the 1958 Agreement(and of the annexed regulations)".

- "Grey market cars: Everything you need to know to avoid seeing your ride get crushed". 30 August 2013.

- "Marketing emphasis on German E1 type approval" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- "Text of the 1958 Agreement - Transport - UNECE" (PDF). www.unece.org.

- "CETA Means Big Changes For Canadian Automotive Industry". 18 October 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=751039

- "Press Releases".

- "eCFR — Code of Federal Regulations". www.ecfr.gov.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-12-29. Retrieved 2010-12-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "1971 Citröen DS". 12 January 2015.

- Orlove, Raphael. "A Simple Explanation Why America Doesn't Get European Hatchbacks".

- "Global Technical Regulations(GTRs)of UNECE". Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- "OICA un-expert-group-documents". Oica.net. Retrieved 2011-11-13.