Daugava

The Daugava (Latgalian: Daugova; Russian: Западная Двина (Západnaya Dviná), meaning "Western Dvina"; Polish: Dźwina), is a river rising in the Valdai Hills, flowing through Russia, Belarus, and Latvia and into the Gulf of Riga. The total length of the river is 1,020 km (630 mi),[1] of which 325 km (202 mi) are in Russia.

| Daugava Western Dvina, Russian: Западная Двина (Západnaya Dviná), Belarusian: Заходняя Дзвіна ([zaˈxodnʲaja dzʲvʲiˈna]), Livonian: Vēna, Estonian: Väina, German: Düna | |

|---|---|

The drainage basin of the Daugava | |

| Location | |

| Country | Belarus, Latvia, Russia, Lithuania, Estonia |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Valdai Hills, Russia |

| • elevation | 221 m (725 ft) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Gulf of Riga, Baltic Sea |

• coordinates | 57°3′42″N 24°1′50″E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 1,020 km (630 mi)[1] |

| Basin size | 87,900 km2 (33,900 sq mi)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 678 m3/s (23,900 cu ft/s) |

Geography

The total catchment area of the river is 87,900 km2 (33,900 sq mi), 33,150 km2 (12,800 sq mi) of which are within Belarus.[1]

Etymology

According to Max Vasmer's Etymological Dictionary, the toponym Dvina clearly cannot stem from a Uralic language, and it possibly comes from an Indo-European word which used to mean river or stream.[2]

Environment

The river began experiencing environmental deterioration in the era of Soviet collective agriculture (producing considerable adverse water pollution runoff) and a wave of hydroelectric power projects.[3]

Cities, towns and settlements

Russia

Andreapol, Zapadnaya Dvina and Velizh.

Belarus

Ruba, Vitebsk, Beshankovichy, Polotsk with Boris stones strewn in the vicinity, Navapolatsk, Dzisna, Verkhnedvinsk, and Druya.

Latvia

Krāslava, Daugavpils, Līvāni, Jēkabpils, Pļaviņas, Aizkraukle, Jaunjelgava, Lielvārde, Kegums, Ogre, Ikšķile, Salaspils and Riga.

History

Humans have settled at the mouth of the Daugava and around the other shores of the Gulf of Riga for millennia, initially participating in a hunter-gatherer economy and utilizing the waters of the Daugava estuary as fishing and gathering areas for aquatic biota. Beginning around the sixth century AD, Viking explorers crossed the Baltic Sea and entered the Daugava River, navigating upriver into the Baltic interior.[4]

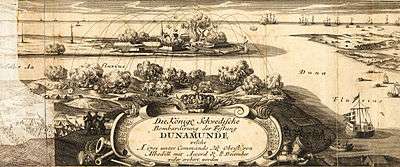

In medieval times the Daugava was an important area of trading and navigation - part of the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks - for transport of furs from the north and of Byzantine silver from the south. The Riga area, inhabited by the Finnic-speaking Livs, became a key element of settlement and defence of the mouth of the Daugava at least as early as the Middle Ages, as evidenced by the now destroyed fort at Torņakalns on the west bank of the Daugava at present day Riga. Since the Late Middle Ages the western part of the Daugava basin has come under the rule of various peoples and states; for example the Latvian town of Daugavpils, located on the western Daugava, variously came under papal rule as well as Slavonic, Polish, German and Russian sway until restoration of the Latvian independence in 1990 at the end of the Cold War.

Water quality

Upstream of the Latvian town of Jekabpils the pH has a characteristic value of about 7.8 (slight alkaline); in this reach the calcium ion has a typical concentration of around 43 milligrams per liter; nitrate has a concentration of about 0.82 milligrams per liter (as nitrogen); phosphate ion is measured at 0.038 milligrams per liter; and oxygen saturation was measured at eighty percent. The high nitrate and phosphate load of the Daugava is instrumental to the buildup of extensive phytoplankton biomass in the Baltic Sea; other European rivers contributing to such high nutrient loading of the Baltic are the Oder and Vistula Rivers.

In Belarus, water pollution of the Daugava is considered moderately severe, with the chief sources being treated wastewater, fish-farming and agricultural chemical runoff (e.g. herbicides, pesticides, nitrate and phosphate).

References

- "Main Geographic Characteristics of the Republic of Belarus. Main characteristics of the largest rivers of Belarus". Land of Ancestors. Data of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection of the Republic of Belarus. 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Фасмер, Макс. Этимологический словарь Фасмера (in Russian). p. 161.

- C.Michael Hogan (2012). "Daugava River". Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment.

-

Compare:

Frucht, Richard C. (2005-01-01). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576078006. Retrieved 2017-07-06.

The Daugava was an important transit river (carrying everything from Vikings to floating lumber) for centuries [...].