Dzungaria

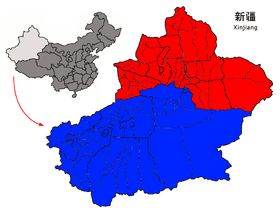

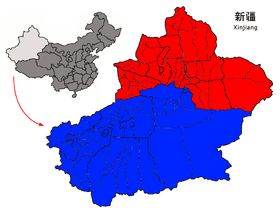

Dzungaria (/(d)zʊŋˈɡɛəriə/; also spelled Zungaria, Dzungharia,Zungharia, Dzhungaria, Zhungaria, Djungaria, Jungaria or Songaria) is a geographical region in northwest China corresponding to the northern half of Xinjiang, also known as Beijiang (Chinese: 北疆; pinyin: Běijiāng; lit.: 'Northern Xinjiang').[2] Bounded by the Tian Shan mountain range to the south and the Altai Mountains to the north, it covers approximately 777,000 km2 (300,000 sq mi), extending into Western Mongolia and Eastern Kazakhstan. Formerly the term could cover a wider area, conterminous with the Dzungar Khanate, a state led by the Oirats in the 18th century which was based in the area.

| Dzungaria | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dzungaria | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 準噶爾 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 准噶尔 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Beijiang | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 北疆 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Northern Xinjiang | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Зүүнгарын нутаг | ||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||

| Uyghur | جوڭغار (Junghariyä)[1] | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Russian name | |||||||||||

| Russian | Джунгария | ||||||||||

| Romanization | Dzhungariya | ||||||||||

Although geographically, historically and ethnically distinct from the Turkic-speaking Tarim Basin area, the Qing dynasty and subsequent Chinese governments integrated both areas into one province, Xinjiang. As the center of Xinjiang's heavy industry, generator of most of Xinjiang's GDP, as well as containing its political capital Ürümqi ("beautiful pasture" in Oirat), Northern Xinjiang continues to attract intraprovincial and interprovincial migration to its cities. In comparison to southern Xinjiang (Nanjiang, or the Tarim Basin), Dzungaria is relatively well integrated with the rest of China by rail and trade links.[3]

Etymology

The name Dzungaria or Zungharia is derived from the Mongolian term "Zűn Gar" or "Jüün Gar" depending on the dialect of Mongolian used. "Zűn"/"Jüün" means "left" and "Gar" means "hand". The name originates from the notion that the Western Mongols are on the left-hand side when the Mongol Empire began its division into East and West Mongols. After this fragmentation, the western Mongolian nation was called "Zuun Gar".

Background

Xinjiang consists of two main geographically, historically, and ethnically distinct regions, Dzungaria north of the Tianshan Mountains and the Tarim Basin south of the Tianshan Mountains, before Qing China unified them into one political entity called Xinjiang province in 1884. At the time of the Qing conquest in 1759, Dzungaria was inhabited by steppe dwelling, nomadic Tibetan Buddhist Dzungar people, while the Tarim Basin was inhabited by sedentary, oasis dwelling, Turkic speaking Muslim farmers, now known as the Uyghur people.

The Qing dynasty was well aware of the differences between the former Buddhist Mongol area to the north of the Tianshan and Turkic Muslim south of the Tianshan, and ruled them in separate administrative units at first.[4] However, Qing people began to think of both areas as part of one distinct region called Xinjiang .[5] The very concept of Xinjiang as one distinct geographic identity was created by the Qing and it was originally not the native inhabitants who viewed it that way, but rather it was the Chinese who held that point of view.[6] During the Qing rule, no sense of "regional identity" was held by ordinary Xinjiang people; rather, Xinjiang's distinct identity was given to the region by the Qing, since it had distinct geography, history and culture, while at the same time it was created by the Chinese, multicultural, settled by Han and Hui, and separated from Central Asia for over a century and a half.[7]

In the late 19th century, it was still being proposed by some people that two separate parts be created out of Xinjiang, the area north of the Tianshan and the area south of the Tianshan, while it was being argued over whether to turn Xinjiang into a province.[8]

Dzungarian Basin

The core of Dzungaria is the triangular Dzungarian Basin, also known as Jungar Basin, or in Chinese as simplified Chinese: 准噶尔盆地; traditional Chinese: 準噶爾盆地; pinyin: Zhǔngá'ěr Péndì, with its central Gurbantünggüt Desert. It is bounded by the Tian Shan to the south, the Altai Mountains to the northeast and the Tarbagatai Mountains to the northwest.[9] The three corners are relatively open. The northern corner is the valley of the upper Irtysh River. The western corner is the Dzungarian Gate, a historically important gateway between Dzungaria and the Kazakh Steppe; presently, a highway and a railway (opened in 1990) run through it, connecting China with Kazakhstan. The eastern corner of the basin leads to Gansu and the rest of China. In the south, an easy pass leads from Ürümqi to the Turfan Depression. In the southwest, the tall Borohoro Mountains branch of the Tian Shan separates the basin from the upper Ili River.

The basin is similar to the larger Tarim Basin on the southern side of the Tian Shan Range. Only a gap in the mountains to the north allows moist air masses to provide the basin lands with enough moisture to remain semi-desert rather than becoming a true desert like most of the Tarim Basin and allows a thin layer of vegetation to grow. This is enough to sustain populations of wild camels, jerboas, and other wild species.[10]

The Dzungarian Basin is a structural basin with thick sequences of Paleozoic-Pleistocene rocks with large estimated oil reserves.[11] The Gurbantunggut Desert, China’s second largest, is in the center of the basin.[12]

The Dzungarian basin does not have a single catchment center. The northernmost section of Dzungaria is part of the basin of the Irtysh River, which ultimately drains into the Arctic Ocean. The rest of the region is split into a number of endorheic basins. In particular, south of the Irtysh, the Ulungur River ends up in the (presently) endorheic Lake Ulungur. The Southwestern part of the Dzungarian basin drains into the Aibi Lake. In the west-central part of the region, streams flow into (or toward) a group of endorheic lakes that include Lake Manas and Lake Ailik. During the region's geological past, a much larger lake (the "Old Manas Lake") was located in the area of today's Manas Lake; it was fed not only by the streams that presently flow toward it but also by the Irtysh and Ulungur, which too were flowing toward the Old Manas Lake at the time.[13]

The cold climate of nearby Siberia influences the climate of the Dzungarian Basin, making the temperature colder—as low as −4 °F (−20 °C)—and providing more precipitation, ranging from 3 to 10 inches (76 to 254 mm), compared to the warmer, drier basins to the south. Runoff from the surrounding mountains into the basin supplies several lakes. The ecologically rich habitats traditionally included meadows, marshlands, and rivers. However, most of the land is now used for agriculture.[10]

It is a largely steppe and semi-desert basin surrounded by high mountains: the Tian Shan (ancient Mount Imeon) in the south and the Altai in the north. Geologically it is an extension of the Paleozoic Kazakhstan Block and was once part of an independent continent before the Altai mountains formed in the late Paleozoic. It does not contain the abundant minerals of Kazakhstan and may have been a pre-existing continental block before the Kazakhstan Block was formed.

Ürümqi, Yining and Karamai are the main cities; other smaller oasis towns dot the piedmont areas.

Paleontology

Dzungaria and its derivatives are used to name a number of pre-historic animals[14] hailing from the rocky outcrops located in the Dzungar Basin:

- Dsungaripterus weii (pterosaur)

- Junggarsuchus sloani (crocodylomorph)

A recent notable find, in February 2006, is the oldest tyrannosaur fossil unearthed by a team of scientists from George Washington University who were conducting a study in the Dzungarian Basin. The species, named Guanlong, lived 160 million years ago, more than 90 million years before the famed Tyrannosaurus rex.

Ecology

Dzungaria is home to a semi-desert steppe ecoregion known as the Dzungarian Basin semi-desert. The vegetation consists mostly of low scrub of Anabasis brevifolia. Taller shrublands of saxaul bush (Haloxylon ammodendron) and Ephedra przewalskii can be found near the margins of the basin. Streams descending from the Tian Shan and Altai ranges support stands of poplar (Populus diversifolia) together with Nitraria roborovsky, N. sibirica, Achnatherum splendens, tamarisk (Tamarix sibirimosissima), and willow (Salix ledebouriana).

The northeastern portion of the Dzungarian Basin semi-desert lies within Great Gobi National Park, and is home to herds of Onagers (Equus hemionus), goitered gazelles (Gazella subgutturosa) and Wild Bactrian camels (Camelus ferus).

The basin was one of the last habitats of Przewalski's horse (Equus przewalskii), also known as Dzungarian horse, which was once extinct in the wild, though it has since been reintroduced in areas of Mongolia and China.

History

The first people to inhabit the region were Indo-European-speaking peoples such as the Tocharians in prehistory and the Jushi Kingdom in the first millennium BC.[15][16]

Before the 21st century, all or part of the region has been ruled or controlled by the Xiongnu Empire, Han dynasty, Xianbei state, Rouran Khaganate, Turkic Khaganate, Tang Dynasty, Uyghur Khaganate, Liao dynasty, Kara-Khitan Khanate, Mongol Empire, Yuan Dynasty, Chagatai Khanate, Moghulistan, Qara Del, Northern Yuan, Four Oirat, Dzungar Khanate, Qing Dynasty, the Republic of China and, since 1950, the People's Republic of China.

One of the earliest mentions of the Dzungaria region occurs when the Han dynasty dispatched an explorer to investigate lands to the west, using the northernmost Silk Road trackway of about 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) in length, which connected the ancient Chinese capital of Xi'an to the west over the Wushao Ling Pass to Wuwei and emerged in Kashgar.[17]

Istämi of the Göktürks received the lands of Dzungaria as an inheritance after the death of his father in the latter half of the sixth century AD.[18]

Dzungaria is named after a Mongolian kingdom which existed in Central Asia during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It derived its name from the Dzungars, who were so called because they formed the left wing (züün, left; gar, hand) of the Mongolian army, self-named Oirats.[19] Dzungar power reached its height in the second half of the 17th century, when Galdan Boshugtu Khan repeatedly intervened in the affairs of the Kazakhs to the west, but it was completely destroyed by the Qing Empire about 1757–1759. It has played an important part in the history of Mongolia and the great migrations of Mongolian stems westward. Its widest limit included Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, the whole region of the Tian Shan, and the greater proportion of that part of Central Asia which extends from 35° to 50° N and from 72° to 97° E.[19]

After 1761, its territory fell mostly to the Qing dynasty during the campaign against the Dzungars (Xinjiang and north-western Mongolia) and partly to Russian Turkestan (the earlier Kazakh state provinces of Zhetysu and Irtysh river).

After the Dzungar genocide, the Qing subsequently began to repopulate the area with Han and Hui people from China Proper.

The population in the 21st century consists of Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Mongols, Uyghurs and Han Chinese. Since 1953, northern Xinjiang has attracted skilled workers from all over China—who have mostly been Han Chinese—to work on water conservation and industrial projects, especially the Karamay oil fields. Intraprovincial migration has mostly been directed towards Dzungaria also, with immigrants from the poor Uyghur areas of southern Xinjiang flooding to the provincial capital of Ürümqi to find work.

As a political or geographical term Dzungaria has practically disappeared from the map; but the range of mountains stretching north-east along the southern frontier of the Zhetysu, as the district to the southeast of Lake Balkhash preserves the name of Dzungarian Alatau.[19] It also gave name to Djungarian hamsters.

Dzungaria and the Silk Road

A traveller going west from China must go either north of the Tian Shan mountains through Dzungaria or south of the mountains through the Tarim Basin. Trade usually took the south side and migrations the north. This is most likely because the Tarim leads to the Ferghana Valley and Iran, while Dzungaria leads only to the open steppe. The difficulty with south side was the high mountains between the Tarim and Ferghana. There is also another reason. The Taklamakan is too dry to support much grass, and therefore nomads when they are not robbing caravans. Its inhabitants live mostly in oases formed where rivers run out of the mountains into the desert. These are inhabited by peasants who are unwarlike and merchants who have an interest in keeping trade running smoothly. Dzungaria has a fair amount of grass, few towns to base soldiers in and no significant mountain barriers to the west. Therefore, trade went south and migrations north.[20] Today most trade is north of the mountains (Dzungarian Gate and Khorgas in the Ili valley) to avoid the mountains west of the Tarim and because Russia is currently more developed.

Economy

Wheat, barley, oats, and sugar beets are grown, and cattle, sheep, and horses are raised. The fields are irrigated with melted snow from the permanently white-capped mountains.

Dzungaria has deposits of coal, gold, and iron, as well as large oil fields.

See also

- Shishugou Formation dinosaur traps

References

Citations

- David Brophy (4 April 2016). Uyghur Nation: Reform and Revolution on the Russia-China Frontier. Harvard University Press. pp. 319–. ISBN 978-0-674-97046-5.

- S. Frederick Starr (15 March 2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-7656-3192-3.

- Stahle, Laura N (August 2009). "Ethnic Resistance and State Environmental Policy: Uyghurs and Mongols" (PDF). University of southern California.

- Liu & Faure 1996, p. 69.

- Liu & Faure 1996, p. 70.

- Liu & Faure 1996, p. 67.

- Liu & Faure 1996, p. 77.

- Liu & Faure 1996, p. 78.

- "Jungar Basin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "Junggar Basin semi-desert". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2010-03-08. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- "Geochemistry of oils from the Junggar Basin, Northwest China". AAPG Bulletin, GeoScience World. 1997. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- "Junggar Basin semi-desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- Yao, Yonghui; Li, Huiguo (2010), "Tectonic geomorphological characteristics for evolution of the Manas Lake", Journal of Arid Land, 2 (3): 167–173

- Nature, Nature Publishing Group, Norman Lockyer, 1869

- Hill (2009), p. 109.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 35, 37, 42. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- Silk Road, North China, C.Michael Hogan, the Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham

- The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, By René Grousset

-

- Grosset, 'The Empire of the Steppes', p xxii,

Sources

- Andreyev, Alexandre (2003). Soviet Russia and Tibet: The Debarcle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918-1930s. Volume 4 of Brill's Tibetan Studies Library (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 9004129529. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Andreyev, Alexandre (2014). The Myth of the Masters Revived: The Occult Lives of Nikolai and Elena Roerich. BRILL. ISBN 9004270434. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baabar (1999). Kaplonski, Christopher (ed.). Twentieth Century Mongolia, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). White Horse Press. ISBN 1874267405. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baabar, Bat-Ėrdėniĭn Baabar (1999). Kaplonski, Christopher (ed.). History of Mongolia (illustrated, reprint ed.). Monsudar Pub. ISBN 9992900385. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bovingdon, Gardner (2010), The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0231519419CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hopper, Ben; Webber, Michael (2009), Migration, Modernisation and Ethnic Estrangement: Uyghur migration to Urumqi, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, PRC, Inner Asia, 11, Global Oriental Ltd, pp. 173–203CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sautman, Barry (2000), "Is Xinjiang an Internal Colony?", Inner Asia, Brill, 2 (33, number 2): 239–271CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Qiu, Yuanyao (1994), 跨世纪的中国人口:新疆卷 [China's population across the centuries: Xinjiang volume], Beijing: 中国统计出版社CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Volume 23 (9 ed.). Maxwell Sommerville. 1894. Retrieved 10 March 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harvard Asia Quarterly, Volume 9. Harvard University. Asia Center, Harvard Asia Law Society, Harvard Asia Business Club, Asia at the Graduate School of Design (Harvard University). Harvard Asia Law Society, Harvard Asia Business Club, and Asia at the Graduate School of Design. 2005. Retrieved 10 March 2014.CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Linguistic Typology, Volume 2. Association for Linguistic Typology. Mouton de Gruyter. 1998. Retrieved 10 March 2014.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 10. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. North-China Branch. Shanghai : Printed at the "Celestial Empire" Office 10-Hankow Road-10.: The Branch. 1876. Retrieved 10 March 2014.CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: location (link)

- Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. North China Branch, Shanghai (1876). Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 10. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. North-China Branch. Shanghai : Printed at the "Celestial Empire" Office 10-Hankow Road-10.: Kelly & Walsh. Retrieved 10 March 2014.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1871). Parliamentary Papers, House of Commons and Command, Volume 51. H.M. Stationery Office. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1914). Papers by Command, Volume 101. H.M. Stationery Office. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Great Britain. Foreign Office. Historical Section, George Walter Prothero (1920). Handbooks Prepared Under the Direction of the Historical Section of the Foreign Office, Issues 67-74. H.M. Stationery Office. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Great Britain. Foreign Office. Historical Section (1973). George Walter Prothero (ed.). China, Japan, Siam. Volume 12 of Peace Handbooks, Great Britain. Foreign Office. Historical Section. ISBN 0842017046. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Ethnological information on China (1960–1969). Volume 16; Volume 620 of JPRS (Series). CCM Information Corporation. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Bellér-Hann, Ildikó, ed. (2007). Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia (illustrated ed.). Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0754670414. ISSN 1759-5290. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- BURNS, JOHN F. (July 6, 1983). "ON SOVIET-CHINA BORDER, THE THAW IS JUST A TRICKLE". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Bretschneider, E. (1876). Notices of the Mediæval Geography and History of Central and Western Asia. Trübner & Company. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Bridgman, Elijah Coleman; Williams, Samuel Wells (1837). The Chinese Repository (reprint ed.). Maruzen Kabushiki Kaisha. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- The Chinese Repository, Volume 5 (reprint ed.). Kraus Reprint. 1837. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Britannica Educational Publishing (2010). Pletcher, Kenneth (ed.). The Geography of China: Sacred and Historic Places. Britannica Educational Publishing. ISBN 1615301828. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Britannica Educational Publishing (2011). Pletcher, Kenneth (ed.). The Geography of China: Sacred and Historic Places (illustrated ed.). The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 1615301348. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Victor C. Falkenheim. "Xinjiang - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. p. 2. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- Benson, Linda; Svanberg, Ingvar C. (1998). China's Last Nomads: The History and Culture of China's Kazaks (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1563247828. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Clarke, Michael E. (2011). Xinjiang and China's Rise in Central Asia - A History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1136827064. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Clarke, Michael Edmund (2004). In the Eye of Power: China and Xinjiang from the Qing Conquest to the 'New Great Game' for Central Asia, 1759–2004 (PDF) (Thesis). Griffith University, Brisbane: Dept. of International Business & Asian Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Croner, Don (2009). "False Lama - The Life and Death of Dambijantsan" (PDF). dambijantsan.doncroner.com. Ulaan Baatar: Don Crone. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Croner, Don (2010). "Ja Lama - The Life and Death of Dambijantsan" (PDF). dambijantsan.doncroner.com. Ulaan Baatar: Don Crone. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- Crowe, David M. (2014). War Crimes, Genocide, and Justice: A Global History. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1137037016. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Dunnell, Ruth W.; Elliott, Mark C.; Foret, Philippe; Millward, James A (2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. ISBN 1134362226. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Debata, Mahesh Ranjan (2007). China's Minorities: Ethnic-religious Separatism in Xinjiang. Central Asian Studies Programme (illustrated ed.). Pentagon Press. ISBN 8182743257. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dickens, Mark (1990). "The Soviets in Xinjiang 1911-1949". OXUS COMMUNICATIONS. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Dillon, Michael (2008). Contemporary China - An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 1134290543. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dillon, Michael (2003). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Far Northwest. Routledge. ISBN 1134360967. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dupree, Louis; Naby, Eden (1994). Black, Cyril E. (ed.). The Modernization of Inner Asia. Contributor Elizabeth Endicott-West (reprint ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0873327799. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dwyer, Arienne M. (2007). Salar: A Study in Inner Asian Language Contact Processes, Part 1 (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3447040912. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804746842. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Fairbank, John K., ed. (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 10, Late Ch'ing 1800-1911, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521214475. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Fisher, Richard Swainson (1852). The book of the world, Volume 2. J. H. Colton. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949 (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. ISBN 0521255147. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Garnaut, Anthony (2008). "From Yunnan to Xinjiang : Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals" (PDF). Etudes Orientales N° 25 (1er Semestre 2008). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 17 April 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521497817. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gorelova, Liliya M., ed. (2002). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies, Manchu Grammar. Volume Seven Manchu Grammar. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 9004123075. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Guo, Baogang; Hickey, Dennis V., eds. (2009). Toward Better Governance in China: An Unconventional Pathway of Political Reform (illustrated ed.). Lexington Books. ISBN 0739140299. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Guo, Sujian; Guo, Baogang (2007). Guo, Sujian; Guo, Baogang (eds.). Challenges facing Chinese political development (illustrated ed.). Lexington Books. ISBN 0739120948. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Harris, Rachel (2004). Singing the Village: Music, Memory and Ritual Among the Sibe of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 019726297X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Howell, Anthony J. (2009). Population Migration and Labor Market Segmentation: Empirical Evidence from Xinjiang, Northwest China. Michigan State University. ProQuest. ISBN 1109243235. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Islamic Culture, Volumes 27-29. Islamic Culture Board. Deccan. 1971. ISBN 0842017046. Retrieved 10 March 2014.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Juntunen, Mirja; Schlyter, Birgit N., eds. (2013). Return To The Silk Routes (illustrated ed.). Routledge. ISBN 1136175199. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Kim, Kwangmin (2008). Saintly Brokers: Uyghur Muslims, Trade, and the Making of Qing Central Asia, 1696--1814. University of California, Berkeley. ProQuest. ISBN 1109101260. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Lattimore, Owen; Nachukdorji, Sh (1955). Nationalism and Revolution in Mongolia. Brill Archive. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kim, Hodong (2004). Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804767238. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Lin, Hsiao-ting (2007). "Nationalists, Muslims Warlords, and the "Great Northwestern Development" in Pre-Communist China" (PDF). China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program. 5 (No 1). ISSN 1653-4212. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-09-23.

- Lattimore, Owen (1950). Pivot of Asia; Sinkiang and the inner Asian frontiers of China and Russia. Little, Brown.

- Levene, Mark (2008). "Empires, Native Peoples, and Genocides". In Moses, A. Dirk (ed.). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Oxford and New York: Berghahn. pp. 183–204. ISBN 1-84545-452-9. Retrieved 22 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liew, Leong H.; Wang, Shaoguang, eds. (2004). Nationalism, Democracy and National Integration in China. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0203404297. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295800550. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Liu, Tao Tao; Faure, David (1996). Unity and Diversity: Local Cultures and Identities in China. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9622094023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Lorge, Peter (2006). War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795. Routledge. ISBN 1134372868. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Marks, Robert B. (2011). China: Its Environment and History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 1442212772. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Martin, Robert Montgomery (1847). China ; Political, Commercial, and Social: In an Official Report to Her Majesty's Government. Volume 1 of China, Political, Commercial, and Social: In an Official Report to Her Majesty's Government, China, Political, Commercial, and Social: In an Official Report to Her Majesty's Government. J. Madden. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Martyn, Norma (1987). The silk road. Methuen. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Edme Mentelle; Malte Conrad Brun (dit Conrad) Malte-Brun; Pierre-Etienne Herbin de Halle (1804). Géographie mathématique, physique & politique de toutes les parties du monde, Volume 12. H. Tardieu. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Meehan, Lieutenant Colonel Dallace L. (May–June 1980). "Ethnic Minorities in the Soviet Military implications for the decades ahead". Air University Review. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231139241. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Morozova, Irina Y. (2009). Socialist Revolutions in Asia: The Social History of Mongolia in the 20th Century. Routledge. ISBN 113578437X. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Myer, Will (2003). Islam and Colonialism Western Perspectives on Soviet Asia. Routledge. ISBN 113578583X.

- Nan, Susan Allen; Mampilly, Zachariah Cherian; Bartoli, Andrea, eds. (2011). Peacemaking: From Practice to Theory [2 volumes]: From Practice to Theory. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0313375771. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Nan, Susan Allen; Mampilly, Zachariah Cherian; Bartoli, Andrea, eds. (2011). Peacemaking: From Practice to Theory. Volume One. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0313375763. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Nathan, Andrew James; Scobell, Andrew (2013). China's Search for Security (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231511647. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Newby, L. J. (2005). The Empire And the Khanate: A Political History of Qing Relations With Khoqand C.1760-1860. Volume 16 of Brill's Inner Asian Library (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 9004145508. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Nyman, Lars-Erik (1977). Great Britain and Chinese, Russian and Japanese interests in Sinkiang, 1918-1934. Volume 8 of Lund studies in international history. Esselte studium. ISBN 9124272876. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Paine, S. C. M. (1996). Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and Their Disputed Frontier (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1563247240. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palmer, James (2011). The Bloody White Baron: The Extraordinary Story of the Russian Nobleman Who Became the Last Khan of Mongolia (reprint ed.). Basic Books. ISBN 0465022073. Retrieved 22 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parker, Charles H. (2010). Global Interactions in the Early Modern Age, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1139491415. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Pegg, Carole (2001). Mongolian Music, Dance, & Oral Narrative: Performing Diverse Identities, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295980303. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perdue, Peter C (2005). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 067401684X. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674042026. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C. (October 1996). "Military Mobilization in Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century China, Russia, and Mongolia". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 30 (No. 4 Special Issue: War in Modern China): 757–793. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00016796. JSTOR 312949.

- Pollard, Vincent, ed. (2011). State Capitalism, Contentious Politics and Large-Scale Social Change. Volume 29 of Studies in Critical Social Sciences (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 9004194452. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Powers, John; Templeman, David (2012). Historical Dictionary of Tibet (illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810879840. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Prakash, Buddha (1963). The modern approach to history. University Publishers. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Rahul, Ram (2000). March of Central Asia. Indus Publishing. ISBN 8173871094. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Reed, J. Todd; Raschke, Diana (2010). The ETIM: China's Islamic Militants and the Global Terrorist Threat. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0313365407. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Roberts, John A.G. (2011). A History of China (revised ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0230344119. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Rudelson, Justin Jon; Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam (1992). Bones in the Sand: The Struggle to Create Uighur Nationalist Ideologies in Xinjiang, China (reprint ed.). Harvard University. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Rudelson, Justin Jon; Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam (1997). Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China's Silk Road (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231107870. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Rudelson, Justin Jon; Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam (1997). Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China's Silk Road (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231107862. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- RYAN, WILLIAM L. (Jan 2, 1969). "Russians Back Revolution in Province Inside China". The Lewiston Daily Sun. p. 3. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- M. Romanovski, ed. (1870). "Eastern Turkestan and Dzungaria, and the rebellion of the Tungans and Taranchis, 1862 to 1866 by Robert Michell". Notes on the Central Asiatic Question. Calcutta: Office of Superintendent of Government Printing. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Sanders, Alan J. K. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Mongolia. Volume 74 of Historical Dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East (3, illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810874520. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shelton, Dinah C (2005). Sheltonvolume=, Dinah (ed.). Encyclopedia of genocide and crimes against humanity, Volume 3 (illustrated ed.). Macmillan Reference. ISBN 0028658507. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Sinor, Denis, ed. (1990). Aspects of Altaic Civilization III: Proceedings of the Thirtieth Meeting of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, June 19-25, 1987. 3. Psychology Press. ISBN 0700703802. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Starr, S. Frederick, ed. (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765613182. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Seymour, James D.; Anderson, Richard (1999). New Ghosts, Old Ghosts: Prisons and Labor Reform Camps in China. Socialism and Social Movements Series. Contributor Sidong Fan (illustrated, reprint ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765605104. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Tamm, Eric (2013). The Horse that Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road, and the Rise of Modern China. Counterpoint. ISBN 1582438765. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Theobald, Ulrich (2013). War Finance and Logistics in Late Imperial China: A Study of the Second Jinchuan Campaign (1771–1776). BRILL. ISBN 9004255672. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Tinibai, Kenjali (May 28, 2010). "China and Kazakhstan: A Two-Way Street". Bloomberg Businessweek. p. 1. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Tinibai, Kenjali (2010-05-28). "Kazakhstan and China: A Two-Way Street". Gazeta.kz. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Tinibai, Kenjali (27 May 2010). "Kazakhstan and China: A Two-Way Street". Transitions Online. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Tyler, Christian (2004). Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang (illustrated, reprint ed.). Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813535336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Universität Bonn. Ostasiatische Seminar (1982). Asiatische Forschungen, Volumes 73-75. O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 344702237X. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walcott, Susan M.; Johnson, Corey, eds. (2013). Eurasian Corridors of Interconnection: From the South China to the Caspian Sea. Routledge. ISBN 1135078750. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- Wang, Gungwu; Zheng, Yongnian, eds. (2008). China and the New International Order (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0203932269. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Wayne, Martin I. (2007). China's War on Terrorism: Counter-Insurgency, Politics and Internal Security. Routledge. ISBN 1134106238. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wong, John; Zheng, Yongnian, eds. (2002). China's Post-Jiang Leadership Succession: Problems and Perspectives. World Scientific. ISBN 981270650X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Westad, Odd Arne (2012). Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750 (illustrated ed.). Basic Books. ISBN 0465029361. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Wong, John; Zheng, Yongnian, eds. (2002). China's Post-Jiang Leadership Succession: Problems and Perspectives. World Scientific. ISBN 981270650X. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Zhao, Gang (January 2006). "Reinventing China Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century" (PDF). Modern China. Sage Publications. 32 (Number 1): 3. doi:10.1177/0097700405282349. JSTOR 20062627. Archived from the original on 2014-03-25. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- Znamenski, Andrei (2011). Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia (illustrated ed.). Quest Books. ISBN 0835608913. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Mongolia Society Bulletin: A Publication of the Mongolia Society, Volume 9. Contributor Mongolia Society. The Society. 1970. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mongolia Society (1970). Mongolia Society Bulletin, Volumes 9-12. Mongolia Society. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- France. Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques. Section de géographie (1895). Bulletin de la Section de géographie, Volume 10 (in French). Parus: IMPRIMERIE NATIONALE. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Inner Asia, Volume 4, Issues 1-2. Contributor University of Cambridge. Mongolia & Inner Asia Studies Unit. The White Horse Press for the Mongolia and Inner Asia Studies Unit at the University of Cambridge. 2002. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.CS1 maint: others (link)

- UPI (September 22, 1981). "Radio war aims at China Moslems". The Montreal Gazette. p. 11. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

External links