Dwarf (Middle-earth)

In the fantasy of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Dwarves are a race inhabiting Middle-earth, the central continent of Earth in an imagined mythological past. They are based on the dwarfs of Germanic myths: small humanoids that dwell in mountains, associated with mining, metallurgy, blacksmithing and jewellery.

They appear in his books The Hobbit (1937), The Lord of the Rings (1954–55), the posthumously published The Silmarillion (1977), Unfinished Tales (1980), and The History of Middle-earth series (1983–96), the last three edited by his son and literary executor Christopher Tolkien.

Characteristics

In the appendix on "Durin's Folk" in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien describes dwarves:

They are a tough, thrawn race for the most part, secretive, laborious, retentive of the memory of injuries (and of benefits), lovers of stone, of gems, of things that take shape under the hands of the craftsmen rather than things that live by their own life. But are not evil by nature, and few ever served the Enemy of free will, whatever the tales of Men alleged. For Men of old lusted after their wealth and the work of their hands, and there has been enmity between the races.[T 1]

The J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia considers Tolkien's use of the adjective "thrawn", noting its similarity with Þráinn, a noun meaning "obstinate person". It is also a name found in the Norse list of Dwarf-names, the Dvergatal in the Völuspá, and the name, as Thráin, of two of Thorin's ancestors. It suggests this may have been a philological joke on Tolkien's part.[1]

Dwarves were long-lived, with a lifespan of some 250 years.[T 1][2] They breed slowly, for no more than a third of them are female, and not all marry. Tolkien names only one female, Dís, the sister of Thorin Oakenshield.[3][T 2] They are still considered children in their twenties, as Thorin was at age 24;[T 3] and as "striplings" in their thirties, as Dáin Ironfoot was aged 32.[T 1] They had children starting in their nineties.[T 1]

The Dwarves are described as "the most redoubtable warriors of all the Speaking Peoples"[T 4] - a warlike race who fought fiercely against their enemies, including other Dwarves.[T 5] Highly skilled in the making of weapons and armour, their main weapon was the battle axe, but they also used bows, swords, shields and mattocks, and wore armour.[T 6]

Origins

The Dwarves are portrayed in The Silmarillion as an ancient people who awoke, like the Elves, at the start of the First Age during the Years of the Trees, after the Elves but before the existence of the Sun and Moon. The Vala Aulë, impatient for the arising of the Children of Ilúvatar, created the seven Fathers of the Dwarves in secret, intending them to be his children to whom he could teach his crafts. He also taught them Khuzdul, a language he had devised for them. Ilúvatar, creator of Arda, was aware of the Dwarves' creation and sanctified them. Aulë sealed the seven Fathers of the Dwarves in stone chambers in far-flung regions of Middle-earth to await their awakening.[1][T 7]

Each of the Seven Fathers founded one of the seven Dwarf clans. Durin I was the eldest, and the first of his kind to awake in Middle-earth. He awoke in Mount Gundabad, in the northern Misty Mountains, and founded the clan of Longbeards; they founded the city of Khazad-dûm below the Misty Mountains, and later realms in the Grey Mountains and Erebor (the Lonely Mountain). Two others were laid in sleep in the north of the Ered Luin or Blue Mountains, and they founded the lines of the Broadbeams and the Firebeards.[T 4] After the end of the First Age, the Dwarves spoken of are almost exclusively of Durin's line.[T 8]

A further division, the even shorter Petty-dwarves, is mentioned in The Silmarillion.[T 9][4]

Mining, masonry, and metalwork

As creations of Aulë, they were attracted to the substances of Arda. They mined and worked precious metals throughout the mountains of Middle-earth. They were unrivalled in smithing, crafting, metalworking, and masonry, even among the Elves. The Dwarf-smith Telchar was the greatest in renown.[T 10] They built immense halls under mountains where they built their cities. They built many famed halls including the Menegroth, Khazad-dûm, and Erebor.[T 5] Among the many treasures they forged were the named weapons Narsil, the sword of Elendil, the Dragon-helm of Dor-lómin and the necklace Nauglamír, the most prized treasure in Nargothrond and the most famed Dwarven work of the Elder Days.[T 11]

Language and names

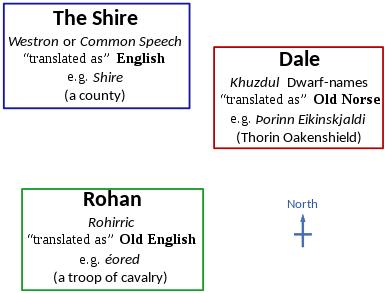

From their creation, the Dwarves spoke Khuzdul, one of Tolkien's invented languages, in the fiction made for them by Aulë, rather than being descended from Elvish, as most of the languages of Men were. They wrote it using Cirth runes, also invented by Tolkien.[6] The Dwarves kept their language secret and did not normally teach it to others, so they learned both Quenya and Sindarin in order to communicate with the Elves, most notably the Noldor and Sindar. By the Third Age, however, the Dwarves were estranged from the Elves and no longer routinely learned their language. Instead, they both used the Westron or Common Speech, which was a Mannish tongue.[T 5][T 13]

In the Grey-elvish or Sindarin the Dwarves were called Naugrim ("Stunted People"), Gonnhirrim ("Stone-lords"), and Dornhoth ("Thrawn Folk"), and Hadhodrim. In Quenya they were the Casári. The Dwarves called themselves Khazâd in their own language, Khuzdul.[T 14]

In reality, Tolkien took the names of twelve of the thirteen dwarves he used in The Hobbit (and the wizard Gandalf's name) from the Old Norse Völuspá.[1][7] When he came to The Lord of the Rings, where he had a proper language for the Dwarves, he was obliged to pretend, in the essay Of Dwarves and Men, that the Old Norse names were translations from Khuzdul, just as the English spoken by the Dwarves to Men and Hobbits was a translation from Westron.[5][T 12][T 4]

Calendar

Tolkien's only mention of the Dwarves' calendar is in The Hobbit, regarding the "dwarves' New Year" or Durin's Day.[T 15] Astronomer Bradley E. Schaefer has analysed the astronomical determinants of Durin's Day. He concluded that – as with many real-world lunar calendars – the date of Durin's Day is observational, dependent on the first visible crescent moon.[8]

Concept and creation

Norse myth

In The Book of Lost Tales, the very few Dwarves who appear are portrayed as evil beings, employers of Orc mercenaries and in conflict with the Elves—who are the imagined "authors" of the myths, and are therefore biased against Dwarves.[T 16][T 17] Tolkien was inspired by the dwarves of Norse myths[9][10] and of Germanic folklore (such as those of the Brothers Grimm), from whom his Dwarves take their characteristic affinity with mining, metalworking, crafting and avarice.[11][12][1]

Jewish history

In The Hobbit, Dwarves are portrayed as occasionally comedic and bumbling, but largely as honourable, serious-minded, but gold-hungry, proud and occasionally officious. Tolkien was now influenced by his own selective reading of medieval texts regarding the Jewish people and their history.[13] The dwarves' characteristics of being dispossessed of their homeland in Erebor, and living among other groups whilst retaining their own culture, are derived from the medieval image of Jews,[13][14] whilst their warlike nature stems from accounts in the Hebrew Bible.[13] Medieval views of Jews also saw them as having a propensity for making well-crafted and beautiful things,[13] a trait shared with Norse dwarves.[10] [15] The Dwarf calendar invented for The Hobbit reflects the Jewish calendar in beginning in late autumn.[13] That they took Bilbo out of his complacent existence has been seen as a metaphor for the "impoverishment of Western society without Jews".[14]

In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien continued the themes of The Hobbit. When giving Dwarves their own language, Khuzdul, Tolkien decided to create an analogue of a Semitic language influenced by Hebrew phonology. Like medieval Jewish groups, the Dwarves used their own language only amongst themselves, and adopted the languages of those they live amongst for the most part, for example taking public names from the cultures they lived within, whilst keeping their "true-names" and true language a secret.[16] Tolkien also invented the Cirth runes, in the fiction said to have been invented by Elves and later adopted by the Dwarves. Tolkien further underlined the diaspora of the Dwarves with the lost stronghold of the Mines of Moria. The main dwarf character Gimli finally reconciled the conflict between Elves and Dwarves through courtesy to the elf-queen Galadriel and forming a deep friendship with the elf Legolas. This has been seen as Tolkien's reply to "Gentile anti-Semitism and Jewish exclusiveness".[14] Tolkien elaborated on Jewish influence on his Dwarves in a letter: "I do think of the 'Dwarves' like Jews: at once native and alien in their habitations, speaking the languages of the country, but with an accent due to their own private tongue..."[T 18] In the last interview before his death, Tolkien briefly says "The dwarves of course are quite obviously, wouldn't you say that in many ways they remind you of the Jews? Their words are Semitic, obviously, constructed to be Semitic."[17] This raises the question, examined by Rebecca Brackmann in Mythlore, of whether there was an element of antisemitism, however deeply buried, in Tolkien's account of the Dwarves, inherited from English attitudes of his time. Brackman notes that Tolkien himself attempted to work through the issue in his Middle-earth writings.[18]

Spelling

The original editor of The Hobbit "corrected" Tolkien's plural dwarves to dwarfs, as did the editor of the Puffin paperback edition of The Hobbit.[T 19] According to Tolkien, the "real 'historical' plural" of dwarf is dwarrows or dwerrows.[19] He referred to dwarves as "a piece of private bad grammar".[T 20] In Appendix F of The Lord of the Rings it is explained that if we still spoke of dwarves regularly, English might have retained a special plural for the word dwarf as with goose—geese.[T 14] Despite Tolkien's fondness for it,[T 14] the form dwarrow only appears in his writing as Dwarrowdelf ("Dwarf-digging"), a name for Moria. Tolkien used Dwarves, instead, corresponding to his Elf and Elves. Tolkien used dwarvish[T 21] and dwarf(-) (e.g. Dwarf-lords, Old Dwarf Road) as adjectives for the people he created.[T 14]

Adaptations

In Ralph Bakshi's 1978 animated film The Lord of the Rings, the part of the Dwarf Gimli was voiced by David Buck.[20]

In Peter Jackson's live action adaptation of The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, Gimli's character is from time to time used as comic relief, whether with jokes about his height or his rivalry with Legolas.[21][22] Gimli is played by John Rhys-Davies, who portrayed the character as having a Scottish accent.[23]

.jpg)

In Iron Crown Enterprises' Middle-earth Role Playing (1986) Dwarven player-characters receive statistical bonuses to Strength and Constitution, and subtractions from Presence, Agility and Intelligence. Seven "Dwarven Kindreds", named after each of the founding fathers—Durin, Bávor, Dwálin, Thrár, Druin, Thelór and Bárin—are given in The Lords of Middle-earth—Volume III (1989).[24]

In Decipher Inc.'s The Lord of the Rings Roleplaying Game (2001), based on the Jackson films, Dwarf player-characters get bonuses to Vitality and Strength attributes and must be given craft skills.[25]

In the real-time strategy game The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth II, and its expansion, both based on the Jackson films, Dwarves are heavily influenced by classical military practice, and use throwing axes, war hammers, spears, and circular or Roman-style shields. One dwarf unit is the "Phalanx", similar to its Greek counterpart.[26]

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- The Return of the King, Appendix A, "Durin's Folk"

- The Peoples of Middle-earth, "The Making of Appendix A": (iv) "Durin's Folk"

- The Hobbit, ch. 1 "An Unexpected Party"

- The Peoples of Middle-earth, part 2, ch. 10 "Of Dwarves and Men"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 10 "Of the Sindar"

- The Hobbit, ch. 15 "The Gathering of the Clouds"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 2 "Of Aulë and Yavanna"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 2 "The Shadow of the Past"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 21 "Of Túrin Turambar"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 2 "Of Aulë and Yavanna"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 22 "Of the Ruin of Doriath"

- Letters, #144, to Naomi Mitchison, 25 April 1954

- The Lord of the Rings, Appendix F, "Of Other Races"

- The Lord of the Rings, Appendix F, "On Translation"

- The Hobbit ch. 3 "A Short Rest"

- The Book of Lost Tales, "Gilfanon's Tale"

- The Book of Lost Tales, "The Nauglafring"

- Letters, #176 to Naomi Mitchison, 8 December 1955

- Letters, #138 to Christopher Tolkien, 4 August 1953

- Letters, #17 to Stanley Unwin, 15 October 1937

- The Hobbit, Preface

Secondary

- Evans, Jonathan (2013) [2007]. "Dwarves". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- A Guide to Tolkien, David Day, Chancellor Press, 2002

- "Dís: The younger sister of Thorin Oakenshield". Encyclopedia of Arda. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Rateliff, John D. (2007). The History of The Hobbit. Part One Mr. Baggins, p. 78. ISBN 0-618-96847-4.

- Shippey, Tom (1982). The Road to Middle-Earth. Grafton (HarperCollins). pp. 131–133. ISBN 0261102753.

- Noel, Ruth S. (1980). The Languages of Tolkien's Middle-earth. Houghton Mifflin. Part 1, ch. 5, "The Languages of Rhovanion", pp. 30–34. ISBN 978-0395291306.

- Rateliff, John D. (2007). Return to Bag-End. The History of The Hobbit. 2. HarperCollins. Appendix III. ISBN 978-0-00-725066-0.

- Schaefer, Bradley E. (1994). "The Hobbit and Durin's Day". The Griffith Observer. Griffith Observatory. 58 (11): 12–17.

- Shippey, Thomas. J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins, 2000

- Chance, Jane, Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader (2004). University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2301-1

- Ashliman, D. L. "Grimm Brothers' Home Page". University of Pittsburgh.

- McCoy, Daniel. "Dwarves". Norse Mythology.

- Rateliff, John. The History of the Hobbit. p.79-80

- Owen Dudley Edwards, British Children's Fiction in the Second World War(2008) Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0-7486-1651-9

- Poetic Edda, translated by Henry Adams Bellows.

- Anderson, Douglas History of the Hobbit, HarperCollins 2006, p. 80

- Gerrolt, Dennis (1971). "Now Read On... interview". BBC. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Brackmann, Rebecca (2010). ""Dwarves are Not Heroes": Antisemitism and the Dwarves in J.R.R. Tolkien's Writing". Mythlore. 28 (3/4). article 7.

- "Dwarf". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-56976-222-6.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2011). Bogstad, Janice M.; Kaveny, Philip E. (eds.). Sometimes One Word Is Worth a Thousand Pictures. Picturing Tolkien: Essays on Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings Film Trilogy. McFarland. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7864-8473-7.

- Brennan Croft, Janet (February 2003). "The Mines of Moria: 'Anticipation' and 'Flattening' in Peter Jackson's The Fellowship of the Ring". Southwest/Texas Popular Culture Association Conference, Albuquerque. University of Oklahoma. Archived from the original on 2011-10-31.

- Sibley, Brian (2013). The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug Official Movie Guide. Harper Collins. p. 27. ISBN 9780007498079.

- Lords of Middle-earth. III. Berkley Publishing. 1989. ISBN 978-1-55806-052-4. OCLC 948478096.

- Long, Steven (2002). The Lord of the rings roleplaying game : core book. Decipher, Inc. ISBN 978-1-58236-951-8. OCLC 51570885.

- "Battle for Middle-earth II - The Dwarves". IGN. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-31555-7

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937), Douglas A. Anderson (ed.), The Annotated Hobbit, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002), ISBN 0-618-13470-0

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Fellowship of the Ring, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955), The Return of the King, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08256-0

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-25730-1

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Peoples of Middle-earth, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-82760-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Book of Lost Tales, 1, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-35439-0

.jpg)