Durvillaea

Durvillaea is a genus of brown algae in the monotypic family Durvillaeaceae. All members of the genus are found in the southern hemisphere, including Australia, New Zealand, South America, and various subantarctic islands.[3][4]

| Durvillaea | |

|---|---|

| |

| D. poha and D. antarctica at Brighton Beach, Otago | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Chromista |

| Phylum: | Ochrophyta |

| Class: | Phaeophyceae |

| Order: | Fucales |

| Family: | Durvillaeaceae (Oltmanns) De Toni |

| Genus: | Durvillaea Bory |

| Type species | |

| D. antarctica | |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

Common name and etymology

The common name for Durvillaea is southern bull kelp, although this is often shortened to bull kelp, which can generate confusion with the North Pacific kelp species Nereocystis luetkeana.[5][6]

The genus is named after French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville (1790-1842).[7]

Description

Durvillaea species are characterised by their prolific growth and plastic morphology.[8]

Two species, D. antarctica and D. poha are buoyant due to a honeycomb-like structure in the fronds of the kelp that holds air.[4][9] When these species detach from the seabed, this buoyancy allows for plants to drift for substantial distances, permitting long distance dispersal.[4][10] In contrast, species as D. willana lack such 'honeycomb' tissue and are non-buoyant, preventing the plants from moving long distances.[10]

Ecology

Durvillaea bull kelp grow within intertidal and shallow subtidal areas, typically on rocky wave-exposed coastal sites.[8] D. antarctica and D. poha are intertidal, whereas D. willana is subtidal (to 6 m depths).[11] Intertidal species can grow at the uppermost limit of the intertidal zone if there is sufficient wave wash.[12] Species can withstand a high level of disturbance from wave action,[8] although storms can remove plants from substrates.[13][14][15]

Epifauna and rafting

Holdfasts of D. antarctica and other species are often inhabited by a diverse array of epifaunal invertebrates, many of which burrow into and graze on the kelp.[16] In New Zealand, epifaunal species include the sea-star Anasterias suteri, crustaceans Parawaldeckia kidderi, P. karaka, Limnoria segnis and L. stephenseni, and the molluscs Cantharidus roseus, Onchidella marginata, Onithochiton neglectus, and Sypharochiton sinclairi.[13][14][15]

Specimens of Durvillaea can detach from substrates, particularly during storms. Once detached, buoyant species such as D. antarctica and D. poha can float as rafts, and can travel vast distances at sea, driven by ocean currents. Kelp-associated invertebrates can be transported inside of drifting kelp holdfasts, potentially leading to long-distance dispersal and a significant impact upon the population genetic structure of the invertebrate species.[13][14][15]

Environmental stressors

Increased temperatures and heatwaves, increased sedimentation, and invasive species (such as Undaria pinnatifida) are sources of physiological stress and disturbance for members of the genus.[17]

A marine heatwave in the summer of 2017/18 appears to have caused the local extinction of multiple Durvillaea species at Pile Bay, on the Banks Peninsula.[18] Once the kelp was extirpated, the invasive kelp Undaria pinnatifida recruited in high densities.[18]

Disturbance from earthquake uplift

Earthquake uplift that raises the intertidal zone by as little as 1.5 metres can cause Durvillaea bull kelp to die off in large numbers.[10][19][20] Increased sedimentation following landslides caused by earthquakes is also detrimental.[19][20] Once an area is cleared of Durvillaea following an uplift event, the bull kelp that re-colonises the area can potentially originate from genetically distinct populations far outside the uplift zone, spread via long distance-dispersal.[21]

Intertidal species of Durvillaea can be used to estimate earthquake uplift height, with comparable results to traditional methods such as lidar.[12] However, since Durvillaea holdfasts often grow at the uppermost limit of the intertidal zone, these uplift estimates are slightly less accurate compared to measures derived from other intertidal kelp such as Carpophyllum maschalocarpum.[12]

Chile

The 2010 Chile earthquake caused significant coastal uplift (~0.2 to 3.1 m), particularly around the Gulf of Arauco, Santa María Island and the Bay of Concepción.[22] This uplift caused large scale die offs of D. antarctica and dramatically affected the intertidal community.[22] The damage to infrastructure and ecological disturbance caused by the earthquake was assessed to be particularly damaging for seaweed gatherers and cochayuyo harvest.[23]

New Zealand

Akatore

Duvillaea bull kelp diversity appears to have been affected by uplift along the Akatore fault zone. Phylogeographic analyses using mitochondrial COX1 sequence data and genotyping by sequencing data for thousands of anonymous nuclear loci, indicate that a historic uplift event (800 - 1400 years before present) along the fault zone and subsequent recolonisation, has left a lasting impact upon the genetic diversity of the of the intertidal species D. antarctica and D. poha, but not on the subtidal species D. willana.[11][24] Such a genetic impact may support the founder takes all hypothesis.[11][24]

Kaikōura

A substantial die off of Durvillaea bull kelp occurred along the Kaikōura coastline following the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake, which caused uplift up to 6 metres.[12][16][19][20][21] The loss of Durvillaea kelp caused ecological disturbance, significantly affecting the biodiversity of the local intertidal community.[19][20] Genetic analysis indicated that some of the Durvillaea that subsequently reached the affected coastline came from areas >1,200 kilometres away.[21]

Wellington and the Wairarapa

It has been hypothesised that gaps in the current geographic range of D. willana around Wellington and the Wairarapa may have been caused by local extinction following historic earthquake uplift events such as the 1855 Wairarapa earthquake.[10] However, uplift along the Akatore fault zone does not appear to have significantly affected the genetic diversity of D. willana in that region, which suggests that earthquake uplift may be insufficient to cause the complete extirpation of this subtidal species.[11]

Species and distribution

There are currently eight recognised species within the genus, and the type species is D. antarctica.[1] All species are restricted to the Southern Hemisphere and many taxa are endemic to particular coastlines or subantarctic islands.

- Durvillaea amatheiae X.A. Weber, G.J. Edgar, S.C. Banks, J.M. Waters & C.I. Fraser, 2017,[25] endemic to southeast Australia.[4][25]

- Durvillaea antarctica (Chamisso) Hariot,[1] found in New Zealand, Chile and various subantarctic islands including Macquarie Island.[3][2][4][6][8][9][24][26][27]

- Durvillaea chathamensis C.H.Hay, 1979,[27] endemic to the Chatham Islands.[4][6]

- Durvillaea fenestrata C. Hay, 2019,[4] endemic in the subantarctic Antipodes Islands.[4][6]

- Durvillaea incurvata (Suhr) Macaya,[4] endemic to Chile.[4]

- Durvillaea poha C.I. Fraser, H.G. Spencer & J.M. Waters, 2012,[9] endemic to South Island of New Zealand, as well as the subantarctic Snares and Auckland Islands.[4][6][9][26]

- Durvillaea potatorum (Labillardière) Areschoug, endemic to southeast Australia.[5][6][28]

- Durvillaea willana Lindauer, 1949,[29] endemic to New Zealand.[3][4][6][10][27][29]

Evolution

A time-calibrated phylogeny of Durvillaea based on four mitochondrial and nuclear DNA markers (COI, rbcL, 28S and 18S) indicates the evolutionary relationships shown in the cladogram below.[4][6] Notably, additional unclassified lineages were estimated within D. antarctica.[4][6]

|

Use of Durvillaea species

Australia

D. potatorum was used extensively for clothing and tools by Aboriginal Tasmanians, with uses including material for shoes and bags to transport freshwater and food.[30][31] Currently, D. potatorum is collected as beach wrack from King Island, where it is then dried as chips and sent to Scotland for phycocolloid extraction.[32]

Chile

D. antarctica and D. incurvata have been used in Chilean cuisine for salads and stews, predominantly by the Mapuche indigenous people who refer to it as collofe or kollof.[4][33] The same species is also called cochayuyo (cocha: lake, and yuyo: weed), and hulte in Quechua.[4][23][34] The kelp harvest, complemented with shellfish gathering, supports artisanal fishing communities in Chile.[34] Exclusive harvest rights are designated using coves or caletas, and the income for fishers (and their unions) often depends upon the sale of cochayuyo.[34]

New Zealand

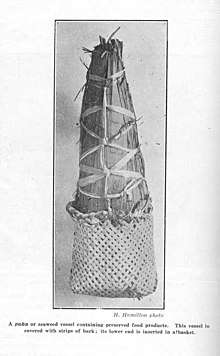

Māori use D. antarctica (rimurapa) and D. poha to make traditional pōhā bags, which are used to transport food and fresh water, to propagate live shellfish, and to make clothing and equipment for sports.[35][36][37] Pōhā are especially associated with Ngāi Tahu and are often used to carry and store muttonbird (tītī) chicks.[35][36] The Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998 protects Durvillaea bull kelp from commercial harvesting within the tribe’s traditional seaweed-gathering areas.[38]

Cochayuyo (D. antarctica) for sale in Chile

Cochayuyo (D. antarctica) for sale in Chile

References

- Bory de Saint-Vincent, J.B.G.M. (1826). Laminaire, Laminaria. In: Dictionnaire Classique d'Histoire Naturelle. (Audouin, I. et al. Eds) Vol. 9, pp. 187-194.

- Dufour, C; Probert, PK; Savage, C (2012). "Macrofaunal colonisation of stranded Durvillaea antarctica on a southern New Zealand exposed sandy beach". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 46 (3): 369–383. doi:10.1080/00288330.2012.676557.

- Hay, Cameron H. (1977). A biological study of Durvillaea antarctica (Chamisso) Hariot and D. willana Lindauer in New Zealand (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). University of Canterbury. hdl:10092/5690.

- Fraser, Ceridwen I.; Velásquez, Marcel; Nelson, Wendy A.; Macaya, Erasmo C.A.; Hay, Cameron (2019). "The biogeographic importance of buoyancy in macroalgae: a case study of the southern bull‐kelp genus Durvillaea (Phaeophyceae), including descriptions of two new species". Journal of Phycology. 56 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1111/jpy.12939. PMID 31642057.

- Cheshire, A.C.; Hallam, N. (2009). "Morphological Differences in the Southern Bull-Kelp (Durvillaea potatorum) throughout South-Eastern Australia". Botanica Marina. 32 (3): 191–198. doi:10.1515/botm.1989.32.3.191. S2CID 83670142.

- Fraser, C.I.; Winter, D.J.; Spencer, H.G.; Waters, J.M. (2010). "Multigene phylogeny of the southern bull-kelp genus Durvillaea (Phaeophyceae: Fucales)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 57 (3): 1301–11. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.10.011. PMID 20971197.

- M. Huisman, John (2000). Marine Plants of Australia. University of Western Australia Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-876268-33-6.

- "Kelp". Australian Antarctic Division: Leading Australia’s Antarctic Program. Department of the Environment and Energy. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- Fraser, Ceridwen I.; Spencer, Hamish G.; Waters, Jonathan M. (2012). "Durvillaea poha sp. nov. (Fucales, Phaeophyceae): a buoyant southern bull-kelp species endemic to New Zealand". Phycologia. 51 (2): 151–156. doi:10.2216/11-47.1. S2CID 86386681.

- Hay, Cameron H. (2019). "Seashore uplift and the distribution of the bull kelp Durvillaea willana Lindauer in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 2019 (2): 94–117. doi:10.1080/0028825X.2019.1679842.

- Parvizi, Elahe; Fraser, Ceridwen I.; Dutoit, Ludovic; Craw, Dave; Waters, Jonathan M. (2020). "The genomic footprint of coastal earthquake uplift". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 287: 20200712. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.0712.

- Reid, Catherine; Begg, John; Mouslopoulou, Vasiliki; Oncken, Onno; Nicol, Andrew; Kufner, Sofia-Katerina (2020). "Using a calibrated upper living position of marine biota to calculate coseismic uplift: a case study of the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake, New Zealand". Earth Surface Dynamics. 8: 351–366. doi:10.5194/esurf-8-351-2020.

- Nikula, Raisa; Fraser, Ceridwen I.; Spencer, Hamish G.; Waters, Jonathan M. (2010). "Circumpolar dispersal by rafting in two subantarctic kelp-dwelling crustaceans". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 405: 221–230. Bibcode:2010MEPS..405..221N. doi:10.3354/meps08523.

- Nikula, Raisa; Spencer, Hamish G.; Waters, Jonathan M. (2013). "Passive rafting is a powerful driver of transoceanic gene flow". Biology Letters. 9 (1): 20120821. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0821. PMC 3565489. PMID 23134782.

- Waters, Jonathan M.; King, Tania M.; Fraser, Ceridwen I.; Craw, Dave (2018). "An integrated ecological, genetic and geological assessment of long-distance dispersal by invertebrates on kelp rafts". Frontiers of Biogeography. 10 (3/4): e40888. doi:10.21425/F5FBG40888.

- Luca, Mondardini (2018). Effect of earthquake and storm disturbances on bull kelp (Durvillaea ssp.) and analyses of holdfast invertebrate communities (Master of Science in Environmental Sciences thesis). University of Canterbury. hdl:10092/15095.

- Thomsen, Mads S.; Mondardini, Luca; Alestra, Tommaso; Gerrity, Shawn; Tait, Leigh; South, Paul M.; Lilley, Stacie A.; Schiel, David R. (2019). "Local Extinction of Bull Kelp (Durvillaea spp.) Due to a Marine Heatwave". Frontiers in Marine Science. 6. doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00084.

- Thomsen, Mads S.; South, Paul M. (2019). "Communities and Attachment Networks Associated with Primary, Secondary and Alternative Foundation Species; A Case Study of Stressed and Disturbed Stands of Southern Bull Kelp". Diversity. 11 (4): 56. doi:10.3390/d11040056.

- Schiel, David R.; Alestra, Tommaso; Gerrity, Shawn; Orchard, Shane; Dunmore, Robyn; Pirker, John; Lilley, Stacie; Tait, Leigh; Hickford, Michael; Thomsen, Mads (2019). "The Kaikōura earthquake in southern New Zealand: Loss of connectivity of marine communities and the necessity of a cross‐ecosystem perspective". Aquatic Conservation. 29 (9): 1520–1534. doi:10.1002/aqc.3122.

- "Kelp forests after the Kaikōura Earthquake". Science Learning Hub. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Peters, Jonette C.; Waters, Jonathan M.; Dutoit, Ludovic; Fraser, Ceridwen I. (2020). "SNP analyses reveal a diverse pool of potential colonists to earthquake-uplifted coastlines". Molecular Ecology. 29 (1): 149–159. doi:10.1111/mec.15303. PMID 31711270.

- Castilla, Juan Carlos; Manríquez, Patricio H.; Camaño, Andrés (2010). "Effects of rocky shore coseismic uplift and the 2010 Chilean mega-earthquake on intertidal biomarker species". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 418: 17–23. doi:10.3354/meps08830.

- Marín, Andrés; Gelcich, Stefan; Araya, Gonzalo; Olea, Gonzalo; Espíndola, Miguel; Castilla, Juan C. (2010). "The 2010 tsunami in Chile: Devastation and survival of coastal small-scale fishing communities". Marine Policy. 34: 1381–1384. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2010.06.010.

- Parvizi, Elahe; Craw, Dave; Waters, Jonathan M. (2019). "Kelp DNA records late Holocene paleoseismic uplift of coastline, southeastern New Zealand". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 520: 18–25. Bibcode:2019E&PSL.520...18P. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2019.05.034.

- Weber, X.A., Edgar, G.J., Banks, S.C., Waters, J.M., and Fraser, C.I. "A morphological and phylogenetic investigation into divergence among sympatric Australian southern bull kelps (Durvillaea potatorum and D. amatheiae sp. nov.)." Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. (2017) 107:630-643.

- Fraser, Ceridwen I.; Hay, Cameron H.; Spencer, Hamish G.; Waters, Jonathan M. (2009). "Genetic and morphological analyses of the southern bull kelp Durvillaea antarctica (Phaeophyceae: Durvillaeales) in New Zealand reveal cryptic species". Journal of Phycology. 45 (2): 436–443. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2009.00658.x. PMID 27033822.

- Cameron H., Hay (1979). "Nomenclature and taxonomy within the genus Durvillaea Bory (Phaeophyceae: Durvilleales Petrov)". Phycologia. 18 (3): 191–202. doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-18-3-191.1.

- Cheshire, Anthony C.; Hallam, Neil D. (1985). "The environmental role of alginates in Durvillaea potatorum (Fucales, Phaeophyta)". Phycologia. 24 (2): 147–153. doi:10.2216/i0031-8884-24-2-147.1.

- Lindauer, V.W. (1949). "Notes on marine algae of New Zealand. I". Pacific Science. 3: 340–352.

- Thurstan, Ruth H.; Brittain, Zoё; Jones, David S.; Cameron, Elizabeth; Dearnaley, Jennifer; Bellgrove, Alecia (2018). "Aboriginal uses of seaweeds in temperate Australia: an archival assessment". Journal of Applied Phycology. 30: 1821–1832. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2010.06.010.

- Murtough, Harry (6 January 2019). "Kelp water carrying sculptures mad by Nannette Shaw win Victorian Aboriginal art award". The Examiner. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Kelp Industries (August 2004). "Proposal for the harvest and export of native flora under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999" (PDF).

- Stuart, Jim (15 April 2010). "Seaweed: Cochayuyo and Luche". Eating Chilean.

- Gelcich, Stefan; Edwards-Jones, Gareth; Kaiser, Michel J.; Castilla, Juan C. (2010). "Co-management Policy Can Reduce Resilience in Traditionally Managed Marine Ecosystems". Ecoystems. 9: 951–966. doi:10.1007/s10021-005-0007-8.

- "Page 4. Traditional use of seaweeds". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 12 Jun 2006. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Traditional Māori food gathering". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "Maori shellfish project wins scholarship". SunLive. 13 May 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "Durvillaea antarctica". New Zealand Plant Conversation Network. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

Further reading

- Adams, N.M. (1994). Seaweeds of New Zealand. Canterbury University Press. ISBN 978-0908812219.

- Morton, J.W.; Miller, M.C. (1973). The New Zealand Seashore. Collins.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Durvillaea |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Durvillaea. |