Man (Middle-earth)

In J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth fiction, such as The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, the terms Man and Men are humans, whether male or female, in contrast to Elves, Dwarves, Orcs, and other humanoid races.[1] Hobbits were a branch of the lineage of Men.[T 1][T 2][T 3]

Critics and commentators have questioned Tolkien's attitude to race, given that good peoples are white and live in the West,[2] while enemies may be "swart" (dark) and live in the East and South.[3][4] However, others note that Tolkien was strongly anti-racist in real life.[5]

Fictional origins

The race of Men in Tolkien's fictional world is the second race of beings, the "younger children", created by the One God, Ilúvatar. Because they awoke at the start of the Years of the Sun, long after the Elves, the elves called them the "afterborn", or in Quenya the Atani, the "Second People". Like Elves, Men first awoke in the East of Middle-earth, spreading all over the continent and developing a variety of cultures and ethnicities. Unlike Tolkien's elves, Men are mortal; when they die, they are released from Arda (Middle-earth) and depart to a world unknown even to the Valar (the gods).[1]

Linguistic origins

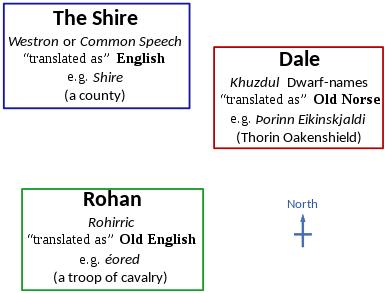

While working on Lord of the Rings, Tolkien found himself searching for an explanation of the Eddaic names of the Dwarves of Dale that he had chosen to use in The Hobbit. Old Norse was a language that did not exist in Middle-earth at the time he was imagining.[2] Tolkien, a philologist, with a special interest in Germanic languages, was driven to pretend that the names and phrases of Old English were translated from Rohirric, the language of Rohan, just as the (modern) English used in The Shire was supposedly translated from Middle-earth's Westron or Common Speech, and the Old Norse of Dale was translated from the secret language of the Dwarves, Khuzdul.[2]

Moral geography

With his different races of Men arranged from good in the West to evil in the East, simple in the North and sophisticated in the South, Tolkien had – in the view of John Magoun, writing in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia – constructed a "fully expressed moral geography".[6] The peoples of Middle-earth vary from the hobbits of The Shire in the Northwest, evil "Easterlings" in the East, and "imperial sophistication and decadence" in the South. Magoun explains that Gondor is both virtuous, being West, and has problems, being South; Mordor in the Southeast is hellish, while Harad in the extreme South "regresses into hot savagery".[6] The film-maker Andrew Stewart, writing in CounterPunch, concurs that the geography of Middle-earth deliberately pits the good West against the evil East.[7] Any moral bias towards the North, however, was directly denied by Tolkien in a letter to Charlotte and Denis Plimmer, who had recently interviewed him in 1967:

Auden has asserted that for me 'the North is a sacred direction'. That is not true. The North-west of Europe, where I (and most of my ancestors) have lived, has my affection, as a man's home should. I love its atmosphere, and know more of its histories and languages than I do of other parts; but it is not 'sacred', nor does it exhaust my affections. I do have, for instance, a particular fondness for the Latin language, and among its descendants for Spanish. That is untrue for my story, a mere reading of the synopses should show. The North was the seat of the fortresses of the Devil.[T 4]

Races

Although all Men in Tolkien's legendarium are related to one another, there are many different groups with different cultures. The friendly races, on the side of the hobbits in The Lord of the Rings, were the [Dun]edain, the men who fought on the side of the Elves in the First Age against Morgoth in Beleriand, from whom the Rangers, including Aragorn, were descended; the Rohirrim; and the men of Gondor.[1]

Sandra Ballif Straubhaar notes in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia that Faramir, Steward of Gondor, makes an "arrogant"[1] speech, of which he later "has cause to repent",[1] classifying the types of Men as seen by the Men of Númenórean origin at the end of the Third Age; she notes, too, that his taxonomy is probably not to be taken at face value.[1]

| High Men Men of the West Númenóreans | Middle Men Men of the Twilight | Wild Men Men of the Darkness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Included | The Three Houses of Edain who went to Númenor, and their descendants | Edain of other houses who stayed in Middle-earth; they became the barbarian nations of Wilderland (Rhovanion), Dale, the House of Beorn, the Rohirrim. | All other Men, not connected to the Eldar (Elves). It is unclear if they came from a house of Edain, or were separately created.[1] Includes Easterlings (allied to the evil Morgoth in the First Age, Sauron in the Third Age) and Dunlendings. |

| Possibly included |

Unclear if the friendly Lossoth (Snow-Men of the Ice Bay of Forochel) and Drúedain (Wood-Woses who helped the Edain in the First Age, and later helped the Rohirrim in the War of the Ring) are part of this group and this taxonomy.[1] |

Status of friendly races

The status of the friendly races has been debated by critics. David Ibata, writing in The Chicago Tribune, asserts that the protagonists in The Lord of the Rings all have fair skin, and they are mainly blond-haired and blue-eyed as well. Ibata suggests that having the "good guys" white and their opponents of other races, in both book and film, is uncomfortably close to racism.[3] The theologian Fleming Rutledge states that the leader of the Drúedain, Ghân-buri-Ghân, is treated as a noble savage.[8][9] Michael N. Stanton writes in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia that Hobbits were "a distinctive form of human beings", and notes that their speech contains "vestigial elements" which hint that they originated in the North of Middle-earth.[10]

Depiction of human adversaries

Two main races of human adversaries are presented in The Lord of the Rings. These are the Haradrim (Southrons) and the Easterlings.[3] The Haradrim were hostile to Gondor, and used elephants in war. Tolkien describes them as "swart" (dark-skinned).[4] Peter Jackson clothes them in long red robes and turbans, and has them riding their elephants, giving them the look in Ibata's opinion of "North African or Middle Eastern tribesmen".[3] Ibata notes that The Two Towers film companion book, The Lord of the Rings: Creatures, describes them as "exotic outlanders" inspired by "12th century Saracen warriors".[3] The Easterlings lived in Rhûn, the vast eastern region of Middle-earth; they fought in the armies of Morgoth and Sauron. Tolkien describes them as "slant-eyed".[4] In Peter Jackson's film of The Two Towers, the Easterling soldiers are covered in armour, revealing only their "coal-black eyes"[3] through their helmet's eye-slits.[3] Ibata comments that they look Asian, their headgear recalling both Samurai helmets and conical "Coolie" hats.[3]

Ibata suggests that the film's director Peter Jackson may have embodied Tolkien's "racial view of the world".[3] Ibata notes too that in the film the Orcs, a supposedly non-human race, look much like "the worst depictions of the Japanese drawn by American and British illustrators during World War II."[3] The scholar Margaret Sinex notes further that Tolkiens' construction of the Easterlings and Southrons draws on centuries of Christian tradition of creating an "imaginary Saracen".[4] Zakarya Anwar judges that while Tolkien himself was anti-racist, his fantasy writings can certainly be taken the wrong way.[5] Other human adversaries include the Black Númenóreans, good men gone wrong;[11] and the Corsairs of Umbar, defeated rebels of Gondor.[12]

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- Tolkien: The Fellowship of the Ring. Prologue.

- Tolkien: Guide to the Names of the Lord of the Rings, "The Firstborn".

- Carpenter: The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, #131.

- Carpenter: The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, #294.

Secondary

- Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2013) [2007]. "Men, Middle-earth". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 414–417. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). pp. 131–133. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Ibata, David (12 January 2003). "'Lord' of racism? Critics view trilogy as discriminatory". The Chicago Tribune.

- Sinex, Margaret (January 2010). ""Monsterized Saracens," Tolkien's Haradrim, and Other Medieval "Fantasy Products"". Tolkien Studies. 7 (1): 175–176. doi:10.1353/tks.0.0067.

- Anwar, Zakarya (June 2009). "An evaluation of a post-colonial critique of Tolkien". Diffusion. 2 (1): 1–9.

- Magoun, John F. G. (2006). "South, The". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 622–623. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- Stewart, Andrew (29 August 2018). "From the Shire to Charlottesville: How Hobbits Helped Rebuild the Dark Tower for Scientific Racism". CounterPunch. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Rutledge, Fleming (2004). The Battle for Middle-earth: Tolkien's Divine Design in The Lord of the Rings. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-8028-2497-4.

- Stanton, Michael N. (2002). Hobbits, Elves, and Wizards: Exploring the Wonders and Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien's "The Lord of the Rings". Palgrave Macmillan. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-4039-6025-2.

- Stanton, Michael N. (2013) [2007]. "Hobbits". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 280–282. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- Hammond and Scull, The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion, p. 283–284.

- Day, David (2015). A Dictionary of Tolkien: A-Z. Octopus. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7537-2855-0.

.jpg)