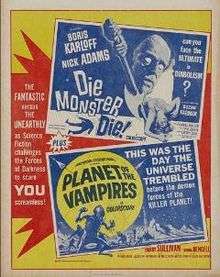

Double feature

The double feature was a motion picture industry phenomenon in which theatres would exhibit two films for the price of one, supplanting an earlier format in which one feature film and various short subject reels would be shown.

Early opera use

Opera houses staged two operas together for the sake of providing long performance for the audience. This was related to one-act or two-act short operas that were otherwise commercially hard to stage alone. A prominent example is the double-bill of Pagliacci with Cavalleria rusticana first staged on 22 December 1893 by the Met. The two operas have since been frequently performed as a double-bill, a pairing referred to in the operatic world colloquially as "Cav and Pag".[1]

Origin and format

The double feature originated in the 1930s. Previous to the 1930s, the dominant presentation model consisted of the following:

- One or more live acts

- An animated cartoon short subject

- One or more live-action comedy shorts

- One or more novelty shorts

- A newsreel

- The main feature film

With the widespread arrival of sound film in American theaters in 1929, many independent exhibitors began dropping the then-dominant presentation model. Movie theaters suffered a downturn in business in the early years of the Great Depression.

Theater owners decided they could both attract more customers and save on costs if they offered two movies for the price of one. The tactic worked, audiences considered the cost of a theater ticket good value for several hours of escapist and varied entertainment, and the practice became a standard pattern of programming.

In the typical 1930s double bill, the screening began with a variety program consisting of trailers, a newsreel, a cartoon and/or a short film preceding a low-budget second feature (the B movie), followed by a short interlude. Lastly, the high-budget main feature (the A movie) ran.

A neighborhood theatre running a double feature won out over a higher-priced first-run theatre with only one feature film. The major studios took note of this, and began making their own B features using the technicians and sets of the studio and featuring stars on their way up or on their way down. The major studios also made film series featuring recurring characters.

Although the double feature put many short comedy producers out of business, it was the primary source of revenue for smaller Hollywood studios, such as Republic and Monogram, that specialized in B movie production.

Decline

The double feature arose partly because of a studio practice known as "block booking," a form of tying in which major Hollywood studios required theaters to buy B-movies along with the more desirable A-movies. The U.S. Supreme Court decided that this practice was illegal in United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. in 1948, contributing to the end of the studio system.

Without block booking, the studios no longer had an incentive to make their own B features. But audiences at first run movie palaces, neighborhood theatres, and drive-in theatres, still expected a program of two features. In 1948 nearly two thirds of the movie houses in the United States were advertising double features.[2]

Following the Supreme Court ruling of 1948, known as the Paramount Consent Decree, the source for the second feature changed.[3] The second feature could be:

- a major studio re-release of an older feature,

- an older feature re-released from firms that specialised in acquiring and rereleasing older films such as Realart and Astor Pictures,

- a low budget feature contracted from a smaller studio.

James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff formed American International Pictures in the mid 1950s to produce and distribute low budget features. Unfortunately they discovered exhibitors were only interested in buying their pictures as supporting features (a B movie) at a flat rate. Once Nicholson and Arkoff combined two features into a program sold as a double bill, each picture given equal billing in the advertising and backed up with an explosive ad campaign, theaters were willing to exhibit on a percentage basis.[4] The exhibitors may have kept a larger share of the box office than the major distributors demanded.[5] But AIP's share of the box office was enough to keep it from going out of business.

The double bill was sold on a percentage basis and each feature was given equal billing in newspaper adds and promotional materials. Since the trailers and advertising promoted the two titles, exhibitors were discouraged from separating the features in the package. To distributors and exhibitors, it was a substantially different policy than the standard double feature in that it was not a top billed A feature combined with a minor billed support feature sold at a flat rate (a B movie).

By the mid 1960s, double features had been mostly abandoned in non–drive-ins in favor of the modern single-feature screening, in which only one feature film is exhibited. However, double bills of popular series that had previously been run as a single feature such as the James Bond and Matt Helm superspy genre and The Man With No Name and The Stranger spaghetti westerns were re-released together by the main studios.

The end of the first run double feature also saw the end of continuous screenings, an exhibition policy where a theater opened at 10:30 or 11am and ran the program without breaks until midnight. Customers bought tickets and entered the theater at anytime during the program.

While most cinemas have discontinued the practice of showing the double feature, it has nostalgia appeal. The Astor Theatre in St Kilda, Melbourne, Australia, established in 1936, continues the tradition of the double feature to this day.

Short films still occasionally precede the feature presentation (Pixar films generally feature a short, for example), but the double feature is now effectively extinct in first-run movie theaters in the U.S.

Following the success of Who Framed Roger Rabbit, three Roger Rabbit cartoon shorts were created to be shown as preludes to other Disney films, in an effort to revive the viewing of cartoon shorts before major films. Only three were made and the scheme failed.[6]

Many repertory houses continue to show two films, usually related in some way, back to back.

During the 1990s, many VHS cassettes that showed two films on the same tape (the second was often a sequel to the first film) were self-named as "double features."

In 2007, filmmakers Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez released their individual films Planet Terror and Death Proof as a double feature under the title Grindhouse, edited together with fake exploitation film trailers and 1970s-era snipes in order to replicate the experience of viewing a double feature in a grindhouse theater. Although Grindhouse received critical acclaim, it was a complete financial flop in the United States. The films were screened individually in international markets and on DVD.

Another recent double feature was the Duel Project, when Japanese directors Ryuhei Kitamura and Yukihiko Tsutsumi created competing films to be shown and voted on by the premier audience.

More recently, two double features of re-released popular films hit the big screen. The first was of the re-release of Toy Story and Toy Story 2 that started October 2, 2009 before the release of Toy Story 3 in the following year. Both films were in Disney Digital 3D in select movie theaters.[7] The second double feature, and the most recent one, was a re-release of Twilight and The Twilight Saga: New Moon for one night only, on June 29, 2010, shortly before the midnight screening of The Twilight Saga: Eclipse in select theaters.[8] In February 2011, it was announced that the 14th Pokémon movie Victini and the Black Hero: Zekrom and Victini and the White Hero: Reshiram, due in July, would be released as a double-feature, though both films are actually "versions" of each other, with differences related to plot points and character designs varying between the version being watched.

References

- Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane (2006). Washington National Opera 1956–2006. Washington, D.C.: Washington National Opera. p. 196. ISBN 0-9777037-0-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "In Praise of the Double Feature" New York Times Hoberman, J.

- p.78 Schatz, Thomas History of the American Cinema: American Cinema in the 1940s. Boom and Bust Volume 6 University of California Press

- Arkoff, Sam (1992). "Flying Through Hollywood by the Seat of My Pants". Birch Lane Press. pp. 46–47.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- p.124 Doherty, Thomas Teenagers and Teenpics Unwin-Hyman 1988

- Double Feature The Dark Crystal + Who Framed Roger Rabbit, September 10, 2009

- Hartford Informer 'Toy Story' Re-Release Provides Trip Down Memory Lane, October 22, 2009

- "Twilight/New Moon Combo (one-night-only)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2011-11-22.