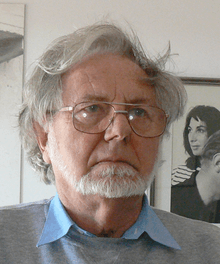

Donald Brook

Donald Brook (born 8 January 1927-died 17 December 2018) was an Australian artist, art critic and theorist whose research and publications centre on the philosophy of art, non-verbal representation and cultural evolution. He initiated the Experimental Art Foundation in Adelaide and was Emeritus Professor of Visual Arts in the Flinders University, Bedford Park, South Australia.

Donald Brook | |

|---|---|

Donald Brook | |

| Born | Donald Brook 8 January 1927 |

| Died | 17 December 2018 (aged 91) |

| Era | 20th Century/21st Century |

| Region | Aesthetics |

Main interests | Philosophy of Art Philosophy of perception Philosophy of science |

Notable ideas | Non-verbal Representation Philosophy of Art Cultural Evolution Cultural Kinds |

Influences

| |

Early life and education

Brook was born in Leeds, Yorkshire and educated on scholarships at Woodhouse Grove School and at the University of Leeds, where he read Electrical Engineering. He left before graduating with the intention of becoming an artist and was conscripted in the army toward the end of WWII. He received a Further Education and Training grant in 1949 to study sculpture at the King Edward VII School of Art in the University of Durham.

After graduating (B.A. Fine arts) with first class honours in 1953 Henry Moore and William Coldstream were his external examiners, he spent a further year on a Chancellor’s postgraduate award researching Archaic and Cycladic sculpture in Greece. Thereafter he established a practice as a sculptor, exhibiting at the Woodstock Gallery in London and executing commissions, and was awarded a studio and residence at the Digswell Arts Trust at Welwyn in Hertfordshire, His interest in unresolved theoretical questions about the visual arts led him to accept a further postgraduate scholarship in the Department of Philosophy in the Australian National University in Canberra in 1962. His PhD thesis (1965), examined by Professors E. H. Gombrich and David Armstrong, applied analytic-philosophical theories of perception to questions of pictorial representation and art-critical appraisal.

He died in Adelaide, Australia.

Professional career

Electing to remain in Australia, Brook continued to work as a sculptor and as art critic of the Canberra Times under John Pringle’s editorship. Later (from 1968) he became art critic of the Sydney Morning Herald when he was appointed as one of the three first academics in the new Power Institute of Fine Arts in the University of Sydney. During this period (1968-1973) he was an energetic initiator of the so-called ‘Tin Sheds’ workshops, where his promotion of what he then called ‘post-object art’–more generally referred to at the time as ‘conceptual art,’ [1]—was found liberating by many of the younger artists. His 1969 John Power Memorial Lecture ‘Flight from the Object’ [2] proposed a radical alternative to the ideas that animated Clement Greenberg’s 1968 Power Lecture ‘Avant-garde Attitudes.’ Australian painters had generally taken their options to be restricted to the choice of international mainstream modernism or the purposeful construction of a distinctively Australian style.

In 1973 he was appointed to the inaugural chair of Fine Arts at the Flinders University, where he contentiously changed the departmental name from ‘Fine Arts’ to ‘Visual Arts.’ He initiated theoretical studies in the psychology and philosophy of visual perception and introduced a study of Aboriginal visual culture in a context where European Art History had previously dominated. At that time no practical studio courses were offered in any Australian University. From 1974 he therefore initiated the Experimental Art Foundation in the city of Adelaide. This was partly designed to enrol practising artists, along with academics and theorists, to bridge what he called ‘the gap between town and gown.’ He also introduced postgraduate academic programs for practising artists.

Brook abandoned art criticism after leaving Sydney, and published extensively thereafter in journals of informed opinion and more popular media as well as in the academic literature. He retired from Flinders at the end of 1989 and lived in Cyprus from 1990–92, returning temporarily to a part-time role at the University of Western Australia before settling again in Adelaide.

Theoretical contributions

Although they are wide-ranging, Brook’s philosophical interests have centred on two principal regions of speculation: to understand the nature and place of perception and non-verbal representation in the visual arts, and to elucidate the relationship between art, the histories of works of art and the dynamics of cultural evolution. His early work on perception was first publicly aired in ‘Perception and the appraisal of sculpture’,[3] in which the important distinction he later draws between matching and simulating non-verbal representational practices is introduced as a difference between what he calls the ‘object accounts’ and the ‘picture accounts’ that we spontaneously give of visually perceived things; notably of three-dimensional works of art. Crucial to his thinking is the idea that non-verbal representation is not a quasi-linguistic form of communication. It relies on the de facto socially efficacious substitutability of one thing for another thing even in cases where relevant properties are not shared. He argues that this perceptually mediated substitutive felicity must have been available to pre-linguistic organisms or language itself could not possibly have evolved.

Brook’s elucidation of the concept of art, as what he at first called ‘experimental modelling of actual and possible worlds,’ is first comprehensively spelled out in his paper ‘A new theory of art’.[4] This rather complex theoretical structure underwent continuous modification in numerous publications as his memetic account of cultural evolution developed. He embraced Dawkins’ concept of the meme as the potent factor in cultural evolution, analogous to the function of the gene in biological evolution. However, he differed significantly from Dawkins and other meme-theorists in his way of understanding and exemplifying the meme. Instead of offering such examples as the popular song or catchphrase he insisted that these things are items of a cultural kind analogous to the items of biological kinds such as a horse, or a cabbage. Just as a horse is the product of appropriately activated genes, he argues that a popular song or a catchphrase is not itself a meme. It is an item of a predictable cultural kind that is generated by exercising memes. Memes are purposefully directed actions that can be exercised in concerted ways, as contrasted with mere behaviours. This is first unambiguously elucidated in his paper ‘Art history?’.[5]

Brook’s account of art as the essentially unexpected recognition of the viability of new memes is spelled out in his book The awful truth about what art is (2008).[6] It is succeeded by his semi-autobiographical book Get A life (2014) [7] in which an anthology of his papers on perception, representation, art, evolution and history is strung together along a string of text that is intended to place them in the context of his personal history and experience.

References

- [1]‘Toward a definition of 'conceptual art.' Leonardo 5 (1972): 49-50.

- [2]The 1969 John Power Lecture in Contemporary Art. Flight from the object. Sydney: Power Institute of Fine Arts, 1970. 1-22. Reprinted in Ed. Bernard Smith, Concerning Contemporary Art, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974 and as "El alejamiento del objeto estetico" in Ed. Bernard Smith, Interpretacion y analysis del ARTE ACTUAL, Trans. Jesus Ortiz, Pamplona: Eunsa, 1977.

- [3]‘Perception and the appraisal of sculpture.’ Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 27 (1969): 323-30.

- [4]‘A new theory of art.’ British Journal of Aesthetics 20 (1980): 305-321.

- [5]‘Art history?’ History and Theory 43 (February 2004), 1-17.

- [6]The awful truth about what art is. Artlink, Adelaide, 2008.

- [7]Get a life. Artlink, Adelaide, 2014.