Dingyuan-class ironclad

The Dingyuan class (simplified Chinese: 定远; traditional Chinese: 定遠; pinyin: Dìngyǔan; Wade–Giles: Ting Yuen or Ting Yuan) consisted of a pair of ironclad warships—Dingyuan and Zhenyuan—built for the Imperial Chinese Navy in the 1880s. They were the first ships of that size to be built for the Chinese Navy, having been constructed by Stettiner Vulcan AG in Germany. Originally expected to be a class of 12 ships, before being reduced to three and then two, with Jiyuan was reduced in size to that of a protected cruiser.

Zhenyuan, following capture by the Imperial Japanese Navy at Weihaiwei | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Dingyuan-class ironclad |

| Builders: | Stettiner Vulcan AG, Stettin, Germany |

| Operators: | |

| Preceded by: | None |

| Succeeded by: | None |

| Cost: | 1,000,000 silver taels |

| Built: | 1881–1884 |

| In service: | 1885–1912 |

| Completed: | 2 |

| Lost: | 1 |

| Scrapped: | 1 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Ironclad turret ship |

| Displacement: | 7,670 long tons (7,793 t) (deep load) |

| Length: | 298.5 ft (91.0 m) |

| Beam: | 60 ft (18 m) |

| Draught: | 20 ft (6.1 m) |

| Installed power: | |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 15.4 knots (28.5 km/h; 17.7 mph) |

| Range: | 4,500 nmi (8,300 km; 5,200 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 363 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: |

|

They were prevented from sailing to China during the Sino-French War, but first saw combat at the Battle of the Yalu River on 17 September 1894, during the First Sino-Japanese War. They were next in combat during the Battle of Weihaiwei in early 1895, where they were blockaded in the harbour. Dingyuen was struck by a torpedo, and was beached where it continued to operate as a defensive fort. When the fleet was surrendered to the Japanese, she was destroyed while Zhenyuan became the first battleship of the Imperial Japanese Navy as Chin'en. She was eventually removed from the Navy list in 1911, and was sold for scrap the following year.

Design

Naval conflicts with Western powers earlier in the 19th century such as the First and Second Opium Wars, during which European warships decisively defeated China's traditional junk fleets, prompted a major rearmament program that began in the 1880s under the Viceroy of Zhili province, Li Hongzhang. Advisers from the British Royal Navy assisted the program, and the first group of ships—several ironclad gunboats and two small cruisers—were bought from British shipyards.[1] Following a dispute with Japan over the island of Formosa, the Chinese Navy decided to buy large ironclad battleships to match the Imperial Japanese Navy ironclads of the Fusō and Kongō classes then under construction. Britain was unwilling to sell China warships of this size for fear of offending the Russian Empire, despite having sold Japan similar vessels, so Li turned to German shipyards.[2]

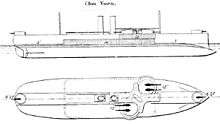

The German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) was completing the four Sachsen-class ironclads, and offered to sell China ships built to a modified design. Li wanted to buy up to 12 large ironclads, but tight finances prevented an order of three ships, of which the Jiyuan was reduced in size to that of a protected cruiser. Rather than mounting the main guns in a pair of large, open barbettes as in the Sachsen class, the new design for placed four guns in two rotating barbettes towards the front of each ship. The two ships of the class, Dingyuan and Zhenyuan, were built at a cost of around 6.2 million German gold marks, the equivalent of around 1 million Chinese silver taels.[2]

General characteristics and machinery

The ships of the Dingyuan class were 308 feet (94 m) long between perpendiculars and 298.5 ft (91.0 m) long overall. They had a beam of 60 ft (18 m) and a draught of 20 ft (6.1 m). The ships displaced 7,144 long tons (7,259 t) as designed and up to 7,670 long tons (7,793 t) at full load. The ships' hulls were constructed out of steel, and were built with a naval ram in the bow. Steering was controlled by a single rudder.[2] Each vessel had a crew of 363 officers and enlisted men. Two heavy military masts were fitted, one just in front of the main battery guns and one behind. A hurricane deck covered the turrets and ran from the foremast to the funnels. Each ship carried a pair of second-class torpedo boats astern of the funnels, along with derricks to unload them.[3]

Dingyuan and Zhenyuan were powered by a pair of horizontal, three-cylinder trunk steam engines, each of which drove a single screw propeller. Steam was provided by eight cylindrical boilers that were ducted into a pair of funnels amidships. The boilers were divided into four boiler rooms. The engines were rated at 6,000 indicated horsepower (4,500 kW) for a top speed of 14.5 knots (26.9 km/h; 16.7 mph), though both ships exceeded these figures on trials, with Zhenyuan, the faster of the two, reaching 7,200 ihp (5,400 kW) and 15.4 kn (28.5 km/h; 17.7 mph). The ships carried 700 long tons (711 t) of coal normally and up to 1,000 long tons (1,016 t); this enabled a cruising radius of 4,500 nautical miles (8,300 km; 5,200 mi) at a speed of 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph). Both ships were fitted with sails for the voyage from Germany to China, though they were later removed.[4]

Armament and armour

The ships were armed with a main battery of four 12 in (305 mm) 20-caliber guns, mounted in two barbettes. The barbettes are sometimes reported to have been in different arrangements on Dingyuan and Zhenyuan, but both ships' guns were arranged identically, with the starboard barbette forward of the port one. The guns themselves were 31.5-long-ton (32 t) Krupp guns.[2] The placement of the guns caused trim problems that led the ships to be wet forward.[5]

The secondary battery consisted of two 5.9 in (150 mm) guns mounted individually, one on the bow and the other on the stern.[2] For defence against torpedo boats, she carried a pair of 47 mm (1.9 in) Hotchkiss revolver cannon and eight 37 mm (1.5 in) Maxim-Nordenfelt quick-firing guns in casemates.[6]

Three 14 in (356 mm) torpedo tubes rounded out the armament; one was mounted in the stern, and the other two were placed forward of the main battery, all above water.[2] They are sometimes reported to have been 15 in (381 mm) torpedo tubes.[6]

The belt armour of the class was 14 in thick, while the barbettes for the main armament were 12 in. A 3 in (76 mm) armoured deck ran the entire length of the ships, leaving the ends undefended. The conning tower had further plating some 8 in (20 cm) thick, while the 5.9 in guns were each in turrets whose armour was somewhere between 0.5 to 3 in (13 to 76 mm) thick.[2]

Ships

| Name | Builder[7] | Laid down[8] | Launched[7] | Commissioned[8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dingyuan | AG Vulcan Stettin | 31 May 1881 | 28 December 1881 | 2 May 1883 |

| Zhenyuan | AG Vulcan Stettin | March 1882 | 28 November 1882 | March 1884 |

Service history

_und_ZHENYUAN_(chin.)_(Kiel_80.681).jpg)

Completed in early 1883 and 1884, respectively, Dingyuan and Zhenyuan were to be sailed to China by a German crew, but delays—primarily from France following the outbreak of the Sino-French War in 1884—kept the ships in Germany. A German crew took Dingyuan out for a firing test at sea, causing glass to shatter around the ship, along with damage to a funnel.[9] After the war ended in April 1885, the two ironclads were permitted to depart for China, along with Jiyuan. The three ships arrived in China in October and they were formally commissioned into the Beiyang Fleet.[10] Dingyuan was the flagship of the new formation, and by the time of the First Sino-Japanese War, she was under the command of Commodore Liu Pu-chan, while Admiral Ding Ruchang was also stationed on board. Zhenyuan was under the command of Captain Lin T'ai-tseng.[11] With the war breaking out in 1894, both ships of the Dingyuan class first saw combat at the Battle of the Yalu River on 17 September.[12]

The two ships formed the middle of the Chinese line of battle,[12] with orders for them to act in support of each other. A shot from Dingyuan at a distance of 6,000 yards (5,500 m) from the Japanese was the first attack of the Chinese fleet, which destroyed its own flying bridge and injured the Admiral and his staff. Her signalling mast was also disabled, causing the Chinese fleet to operate purely in the preassigned pairs throughout the battle.[13] During the course of the battle, the main part of the Japanese fleet concentrated fire on the two ironclads,[14] but the two vessels remained afloat following the Japanese withdrawal as darkness approached. Each ship had been hit by hundreds of shells,[15] but their main armour belts were unpenetrated.[14] Zhenyuan was damaged on 7 November after hitting an unmarked reef, which took her out of active service until the following January.[16]

Both ships were caught in the harbour during the Battle of Weihaiwei in early 1895, with Zhenyuan only partially seaworthy. They were unable to prevent the capture of the port's fortifications by the Japanese, and underwent nightly attacks by torpedo boats.[17] Dingyuan was hit by a torpedo and began to sink. She was quickly beached, where she settled into the mud, and continued to be used as a defensive fort. Admiral Ruchang's flag was subsequently moved across to Zhenyuan.[18] Following Ruchang's suicide, the surrender of the port and the fleet was arranged.[19] Dingyuan was blown up by the Japanese forces, as they were unable to salvage her, although there is a suggestion following an eye witness account that she may have been mined by the Chinese.[20]

Zhenyuan was subsequently recommissioned in the Imperial Japanese Navy as Chin Yen,[20] becoming the first true battleship in the fleet.[21] She was added to Navy list on 16 March, and subsequently rearmed. As other Japanese battleships joined the fleet, she was re-rated as a second class battleship on 21 March 1898, then a first class coastal defence ship on 11 December 1905. During her time under the Japanese flag, she served in the Russo-Japanese War as a convoy escort. She was stricken from the list on 1 April 1911, and used as a target for the Japanese battlecruiser Kurama. She was then sold for scrap on 6 April 1912, while her anchor has been preserved near to the city of Kobe.[22]

See also

Notes

- Wright, pp. 41–49.

- Wright, pp. 50–51.

- Wright, p. 53.

- Wright, pp. 50–51, 53.

- Feng, p. 33.

- Feng, p. 21.

- Gardiner, p. 395.

- Wright, p. 50.

- Wright, p. 54.

- Wright, p. 66.

- Wright, p. 87.

- Wright, p. 90.

- Wright, p. 91.

- Wright, p. 92.

- Wright, p. 93.

- Wright, p. 95–96.

- Wright, p. 99.

- Wright, p. 100.

- Wright, p. 104.

- Wright, p. 105.

- Gardiner, p. 216.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 100.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dingyuan class. |

- Feng, Qing. "The Turret Ship Chen Yuen (1882)". In Taylor, Bruce (ed.). The World of the Battleship: The Lives and Careers of Twenty-One Capital Ships of the World's Navies, 1880–1990. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 0870219065.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Lengerer, Hans & Ahlberg, Lars (2019). Capital Ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy 1868–1945: Ironclads, Battleships and Battle Cruisers: An Outline History of Their Design, Construction and Operations. Volume I: Armourclad Fusō to Kongō Class Battle Cruisers. Zagreb: Despot Infinitus. ISBN 978-953-8218-26-2.

- Wright, Richard N.J. (2000). The Chinese Steam Navy. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-144-6.