Dicistroviridae

Dicistroviridae is a family of viruses in the order Picornavirales. Invertebrates, including aphids, leafhoppers, flies, bees, ants, and silkworms, serve as natural hosts. There are currently 15 species in this family, divided among three genera.[1][2] Diseases associated with this family include: DCV: increased reproductive potential. extremely pathogenic when injected with high associated mortality. CrPV: paralysis and death.[2][3]

| Dicistroviridae | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Molecular surfaces of Triatoma virus (TrV) and Cricket paralysis virus (CrPV) | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Picornavirales |

| Family: | Dicistroviridae |

| Genera | |

| |

Taxonomy

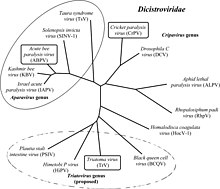

Although many dicistroviruses were initially placed in the Picornaviridae, they have since been reclassified into their own family. The name (Dicistro) is derived from the characteristic dicistronic arrangement of the genome.

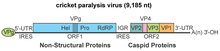

This family is a member of the Order Picornavirales (along with the families Iflaviridae, Picornaviridae, and Secoviridae and Marnaviridae). Within this order, the gene order is the gene order of the nonstructural proteins Hel(helicase)-Pro(protease)-RdRp(polymerase). The Dicistroviridae can be distinguished from the members of the taxa by the location of their structural protein genes at the 3' end rather than the 5' end (as found in Iflavirus, Picornaviridae and Secoviridae) and by having two genomic segments rather than a single one (as in the Comovirus).[2]

Group: ssRNA(+) Order: Picornavirales Family: Dicistroviridae Genus: Aparavirus

- Acute bee paralysis virus

- Israeli acute paralysis virus

- Kashmir bee virus

- Mud crab virus

- Solenopsis invicta virus-1

- Taura syndrome virus

Genus: Cripavirus

- Aphid lethal paralysis virus

- Cricket paralysis virus

- Drosophila C virus

- Rhopalosiphum padi virus

Genus: Triatovirus

- Black queen cell virus

- Himetobi P virus

- Homalodisca coagulata virus-1

- Plautia stali intestine virus

- Triatoma virus

Linepithema humile virus 1 is possibly a member of Dicistroviridae, of unclear placement.

Structure

Viruses in Dicistroviridae are non-enveloped, with icosahedral geometries, and T=pseudo3 symmetry. The diameter is around 30 nm. Genomes are linear and non-segmented, around 8.5-10.2kb in length. The genome has 2 open reading frames.[2][3]

| Genus | Structure | Symmetry | Capsid | Genomic arrangement | Genomic segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aparavirus | Icosahedral | Pseudo T=3 | Non-enveloped | Linear | |

| Cripavirus | Icosahedral | Pseudo T=3 | Non-enveloped | Linear | Monopartite |

Life cycle

Entry into the host cell is achieved by penetration into the host cell. Replication follows the positive stranded RNA virus replication model. Positive stranded RNA virus transcription is the method of transcription. Translation takes place by viral initiation, and ribosomal skipping. Invertebrates serve as the natural host. Transmission routes are contamination.[2][3]

| Genus | Host details | Tissue tropism | Entry details | Release details | Replication site | Assembly site | Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aparavirus | Invertebrates: honeybee, bumblebees | None | Unknown | Unknown | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Unknown |

| Cripavirus | Invertebrates | None | Cell receptor endocytosis | Budding | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Food |

RNA structural elements

Many of the Dicistroviridae genomes contains structured RNA elements. For example, the Cripaviruses have an internal ribosome entry site,[4] which mimics a Met-tRNA and is used in the initiation of translation.[5]

References

- Valles, SM; Chen, Y; Firth, AE; Guérin, DM; Hashimoto, Y; Herrero, S; de Miranda, JR; Ryabov, E; ICTV Report Consortium (March 2017). "ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Dicistroviridae". The Journal of General Virology. 98 (3): 355–356. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000756. PMC 5797946. PMID 28366189.

- "Dicistrovirdae". ICTV Online (10th) Report.

- "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- Kanamori, Y; Nakashima N (2001). "A tertiary structure model of the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) for methionine-independent initiation of translation". RNA. 7 (2): 266–274. doi:10.1017/S1355838201001741. PMC 1370084. PMID 11233983.

- Malys N, McCarthy JEG (2010). "Translation initiation: variations in the mechanism can be anticipated". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 68 (6): 991–1003. doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0588-z. PMID 21076851.

- Hunter, WB, Katsar, CS, Chaparro, JX. 2006. Molecular analysis of capsid protein of Homalodisca coagulata virus-1, a new leafhopper-infecting virus from the glassy-winged sharpshooter, Homalodisca coagulata. Journal of Insect Science 6:31

- Hunnicutt, LE, Hunter, WB, Cave RD, Powell, CA, Mozoruk, JJ. 2006. Genome sequence and molecular characterization of Homalodisca coagulata virus-1, a novel virus discovered in the glassy-winged sharpshooter (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). Virology 350: 67–78

- Valles, SM, Strong, CA, Dang, PM, Hunter, WB, Pereira, RM, Oi, DH, Shapiro, AM, Williams, DF. 2004. A picorna-like virus from the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta: initial discovery, genome sequence, and characterization. Virology 328: 151–157

- De Miranda, Joachim R.; Cordoni, Guido; Budge, Giles (2010). "The Acute bee paralysis virus–Kashmir bee virus–Israeli acute paralysis virus complex". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 103: S30–S47. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.014. PMID 19909972.

External links

- ICTV Online (10th) Report: Dicistroviridae

- Viralzone: Dicistroviridae

- Beediseases Honey bee diseases website by Dr. Guido Cordoni.