Devil's Highway (Roman Britain)

The Devil's Highway was a Roman road in Britain connecting Londinium (London) to Pontes (Staines) and then Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester). The road was the principal route to the west of Britain during the Roman period but was replaced by other routes after the demise of Roman Britain.

Overview

The bridges at Pontes probably crossed Church Island. At Calleva, the road split into three routes continuing west: the Port Way to Sorviodunum (Old Sarum), Ermin Way to Glevum (Gloucester), and the road to Aquae Sulis (Bath). Its name probably derives from later ignorance of its origin and history, having been replaced for travellers by other roads nearby such as Nine Mile Ride, which runs parallel to the Roman road about a mile away but at a lower height.

London

The London portion of the road was rediscovered during Christopher Wren's rebuilding of St Mary-le-Bow church in 1671–73, following the Great Fire. Modern excavations date its construction to the winter from AD 47 to 48. Around London, it was 7.5–8.7 metres (25–29 ft) wide and paved with gravel. It was repeatedly redone, including at least twice before the sack of London by Boudica's troops in 60 or 61.[1] The road ran straight from the bridgehead on the Thames to what would become Newgate on the London Wall before passing over Ludgate Hill and the Fleet, separating into the Devil's Highway and the northwest stretch of Watling Street, going on to Verulamium (St Albans).

Berkshire

The road passes through Windsor Forest and is especially well defined in the large forestry plantations such as those of Swinley Forest before it reaches Crowthorne: it is used both as a footpath and forestry track, and is well preserved in alignment as a result. The road surface is partly metalled with random stones, and is flanked by drainage ditches in most places. The underlying subsoil and geology consists of sand and gravel, and the whole area will have been heathland before the recent plantations of Scots pine and Sitka spruce. There are no modern settlements in the forest, and is now just as lonely as it would have been in Roman times. At several points road cuttings in the soil have been made where the gradient steepens, so as to preserve its linear route through the forest.

It passes about half a mile to the south of Caesar's Camp near Easthampstead, where a smaller road connects to the southern entrance of the hillfort. There is a small Roman settlement known as Wickham Bushes about halfway along this link road, where Roman pottery and other artifacts have been found. It was likely a hospitality stop for travellers on the road. From Crowthorne, the main highway exists as a sand track and footpath through woods and scrub, and at one point (behind Finchampstead Ridges), it crosses a bank which forms the dam to a shallow lake known as Heath pond. Some parts of the land here is owned and managed by the National Trust. The road then passes near to Finchampstead church, where there may have been a Roman signal station or temple.

Hampshire

The Roman road ends at the Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum, the centre for the local Iron Age tribe of the Atrebates. Calleva was a major crossroads. The Devil's Highway connected it with the provincial capital Londinium (London). From Calleva, this road divided into routes to various other points west, including the road to Aquae Sulis (Bath); Ermin Way to Glevum (Gloucester); and the Port Way to Sorviodunum (Old Sarum near modern Salisbury).

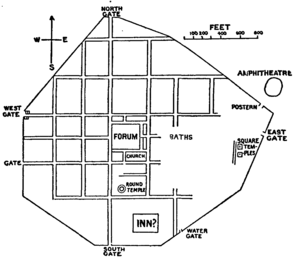

After the Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD an earlier Iron Age settlement developed into the Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum. It was slightly larger, about 40 hectares (99 acres), and was laid out along a distinctive street grid pattern. The town contained a number of public buildings and flourished until the early Anglo-Saxon period. A large mansio was situated near the South Gate, consisting of three wings arranged around a courtyard. The road enters the town near the restored Roman amphitheatre near the eastern gate of the town. The town itself has been well excavated and exposed to viewing in the absence of later development. There is a comprehensive exhibition of finds in the Reading Museum.

See also

References

- Lacey M. Wallace (8 January 2015). The Origin of Roman London. Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-107-04757-0.

Further reading

- MacDougall, P. L. (1858). . Surrey Archaeological Collections. 1: 61–65.

- Lance, E. J. (1858). . Surrey Archaeological Collections. 1: 66–68.