Desmoplasia

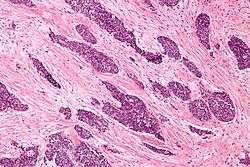

In medicine, desmoplasia is the growth of fibrous or connective tissue.[1] It is also called desmoplastic reaction to emphasize that it is secondary to an insult. Desmoplasia may occur around a neoplasm, causing dense fibrosis around the tumor,[1] or scar tissue (adhesions) within the abdomen after abdominal surgery.[1]

| -plasia and -trophy |

|---|

|

|

Desmoplasia is usually only associated with malignant neoplasms, which can evoke a fibrosis response by invading healthy tissue. Invasive ductal carcinomas of the breast often have a scirrhous, stellate appearance caused by desmoplastic formations.

Terminology

Desmoplasia originates from the Ancient Greek δεσμός desmos, "knot", "bond" and πλάσις plasis, "formation". It is usually used in the description of desmoplastic small round cell tumors.

Neoplasia is the medical term used for both benign and malignant tumors, or any abnormal, excessive, uncoordinated, and autonomous cellular or tissue growth.

Desmoplasia refers to growth of dense connective tissue or stroma.[2] This growth is characterized by low cellularity with hyalinized or sclerotic stroma and disorganized blood vessel infiltration.[3] This growth is called a desmoplastic response and occurs as result of injury or neoplasia.[2] This response is coupled with malignancy in non-cutaneous neoplasias, and with benign or malignant tumors if associated with cutaneous pathologies.[3]

The heterogeneity of tumor cancer cells and stroma cells combined with the complexities of surrounding connective tissue suggest that understanding cancer by tumor cell genomic analysis is not sufficient;[4] analyzing the cells together with the surrounding stromal tissue may provide more comprehensive and meaningful data.

Normal tissue structure and wound response

Normal tissues consist of parenchymal cells and stromal cells. The parenchymal cells are the functional units of an organ, whereas the stromal cells provide the structure of the organ and secrete extracellular matrix as supportive, connective tissue.[3] In normal epithelial tissues, epithelial cells, or parenchymal cells of epithelia, are highly organized, polar cells.[5] These cells are separated from stromal cells by a basement membrane that prevents these cell populations from mixing.[5] A mixture of these cell types is recognized, normally, as a wound, as in the example of a cut to the skin.[6] Metastasis is an example of a disease state in which a breach of the basement membrane barrier occurs.[7]

Cancer

Cancer begins as cells that grow uncontrollably, usually as a result of an internal change or oncogenic mutations within the cell.[8] Cancer develops and progresses as the microenvironment undergoes dynamic changes.[9] The stromal reaction in cancer is similar to the stromal reaction induced by injury or wound repair: increased ECM and growth factor production and secretion, which consequently cause growth of the tissue.[10] In other words, the body reacts similarly to a cancer as it does to a wound, causing scar-like tissue to be built around the cancer. As such, the surrounding stroma plays a very important role in the progression of cancer. The interaction between cancer cells and surrounding tumor stroma is thus bidirectional, and the mutual cellular support allows for the progression of the malignancy.

Growth factors for vascularization, migration, degradation, proliferation

Stroma contains extracellular matrix components such as proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans which are highly negatively charged, largely due to sulfated regions, and bind growth factors and cytokines, acting as a reservoir of these cytokines.[5] In tumors, cancer cells secrete matrix degrading enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that, once cleaved and activated, degrade the matrix, thereby releasing growth factors that signal for the growth of cancer cells.[11] MMPs also degrade ECM to provide space for vasculature to grow to the tumor, for the tumor cells to migrate, and for the tumor to continue to proliferate.[3]

Underlying mechanisms

Desmoplasia is thought to have a number of underlying causes. In the reactive stroma hypothesis, tumor cells cause the proliferation of fibroblasts and subsequent secretion of collagen.[3] The newly secreted collagen is similar to that of collagen in scar formation – acting as a scaffold for infiltration of cells to the site of injury.[12] Furthermore, the cancer cells secrete matrix degrading enzymes to destroy normal tissue ECM thereby promoting growth and invasiveness of the tumor.[3] Cancer associated with a reactive stroma is typically diagnostic of poor prognosis.[3]

The tumor-induced stromal change hypothesis claims that tumor cells can dedifferentiate into fibroblasts and, themselves, secrete more collagen.[3] This was observed in desmoplastic melanoma, in which the tumor cells are phenotypically fibroblastic and positively express genes associated with ECM production.[13] However, benign desmoplasias do not exhibit dedifferentiation of tumor cells.[3]

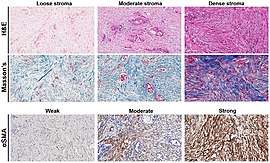

Characteristics of desmoplastic stromal response

A desmoplastic response is characterized by larger stromal cells with increased extracellular fibers and immunohistochemically by transformation of fibroblastic-type cells to a myofibroblastic phenotype.[2] Myofibroblastic cells in tumors are differentiated from fibroblasts for their positive staining of smooth-muscle actin (SMA).[2] Furthermore, an increase in total fibrillar collagens, fibronectins, proteoglycans, and tenascin C are distinctive of the desmoplastic stromal response in several forms of cancer.[14] Expression of tenascin C by breast cancer cells has been demonstrated to allow for metastasis to the lungs and cause the expression of tenascin C by the surrounding tumor stromal cells.[15] In addition, tenascin C is found extensively in pancreatic tumor desmoplasia as well.[16]

Differentiation of scars

While scars are associated with the desmoplastic response of various cancers, not all scars are associated with malignant neoplasms.[3] Mature scars are usually thick, collagenous bundles arranged horizontally with paucicellularity, vertical blood vessels, and no appendages.[3] This is distinguished from desmoplasia in the organization of the tissue, the appendages, and orientation of blood vessels. Immature scars are more difficult to distinguish due to their neoplastic origins.[3] These scars are hypercellular with fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and some immune cells present.[3] The immature scars can be distinguished from desmoplasia by immunohistochemical staining of biopsied tumors that will reveal the type and organization of cells present as well as whether recent trauma has occurred to the tissue.[17]

Examples[3]

Benign condition examples

- Desmoplastic melanocytic naevus

- Desmoplastic spitz naevus

- Desmoplastic cellular blue naevi

- Desmoplastic hairless hypopigmented naevus

- Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma

- Desmoplastic trichilemmoma

- Desmoplastic tumor of the follicular infundibulum

- Sclerotic dermatofibroma

- Desmoplastic fibroblastoma

- Desmoplastic cellular neurothekeoma

- Sclerosing perineurioma

- Microvenular haemangioma

- Immature scars

Malignant condition examples

- Desmoplastic malignant melanoma

- Desmoplastic squamous cell carcinoma

- Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma

- Microcystic adnexal carcinoma

- Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma

- Cutaneous metastasis

Prostate cancer

The stroma of the prostate is characteristically muscular.[2] Due to this muscularity, detecting the myofibroblastic phenotypic change indicative of reactive stroma is difficult in an examination of patient pathologic slides.[2] A diagnosis of reactive stroma associated with prostate cancer is one of poor prognosis.[2]

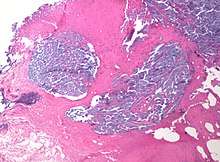

Breast cancer

Clinical presentation of a lump in the breast is histologically viewed as a collagenous tumor or desmoplastic response created by myofibroblasts of the tumor stroma.[18] Proposed mechanisms of activation of myofibroblasts are by immune cytokine signaling, microvascular injury, or paracrine signaling by tumor cells.[18]

References

- "Definition of Desmoplasia". MedicineNet. March 19, 2012.

- Ayala, G; Tuxhorn, JA; Wheeler, TM; Frolov, A; Scardino, PT; Ohori, M; Wheeler, M; Spitler, J; Rowley, DR (2003). "Reactive stroma as a predictor of biochemical-free recurrence in prostate cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 9 (13): 4792–801. PMID 14581350.

- Liu, H; Ma, Q; Xu, Q; Lei, J; Li, X; Wang, Z; Wu, E (2012). "Therapeutic potential of perineural invasion, hypoxia and desmoplasia in pancreatic cancer". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 18 (17): 2395–403. doi:10.2174/13816128112092395. PMC 3414721. PMID 22372500.

- Hanahan, Douglas; Weinberg, Robert A. (2011). "Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation". Cell. 144 (5): 646–74. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. PMID 21376230.

- Alberts, B; Johnson, A; Lewis, J (2008). Molecular Biology of the Cell (5th ed.). Garland Science, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 1164–1165, 1178–1195.

- Mort, Richard L; Ramaesh, Thaya; Kleinjan, Dirk A; Morley, Steven D; West, John D (2009). "Mosaic analysis of stem cell function and wound healing in the mouse corneal epithelium". BMC Developmental Biology. 9: 4. doi:10.1186/1471-213X-9-4. PMC 2639382. PMID 19128502.

- Liotta, LA (1984). "Tumor invasion and metastases: Role of the basement membrane. Warner-Lambert Parke-Davis Award lecture". The American Journal of Pathology. 117 (3): 339–48. PMC 1900581. PMID 6095669.

- Steen, H. B. (2000). "The origin of oncogenic mutations: Where is the primary damage?". Carcinogenesis. 21 (10): 1773–6. doi:10.1093/carcin/21.10.1773. PMID 11023532.

- Kraning-Rush, Casey M.; Califano, Joseph P.; Reinhart-King, Cynthia A. (2012). Laird, Elizabeth G. (ed.). "Cellular Traction Stresses Increase with Increasing Metastatic Potential". PLoS ONE. 7 (2): e32572. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732572K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032572. PMC 3289668. PMID 22389710.

- Troester, M. A.; Lee, M. H.; Carter, M.; Fan, C.; Cowan, D. W.; Perez, E. R.; Pirone, J. R.; Perou, C. M.; et al. (2009). "Activation of Host Wound Responses in Breast Cancer Microenvironment". Clinical Cancer Research. 15 (22): 7020–8. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1126. PMC 2783932. PMID 19887484.

- Foda, Hussein D; Zucker, Stanley (2001). "Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis". Drug Discovery Today. 6 (9): 478–482. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(01)01752-4. PMID 11344033.

- El-Torkey, M; Giltman, LI; Dabbous, M (1985). "Collagens in scar carcinoma of the lung". The American Journal of Pathology. 121 (2): 322–6. PMC 1888060. PMID 3904470.

- Walsh, NM; Roberts, JT; Orr, W; Simon, GT (1988). "Desmoplastic malignant melanoma. A clinicopathologic study of 14 cases". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 112 (9): 922–7. PMID 3415443.

- Kalluri, Raghu; Zeisberg, Michael (2006). "Fibroblasts in cancer". Nature Reviews Cancer. 6 (5): 392–401. doi:10.1038/nrc1877. PMID 16572188.

- Oskarsson, Thordur; Acharyya, Swarnali; Zhang, Xiang H-F; Vanharanta, Sakari; Tavazoie, Sohail F; Morris, Patrick G; Downey, Robert J; Manova-Todorova, Katia; et al. (2011). "Breast cancer cells produce tenascin C as a metastatic niche component to colonize the lungs". Nature Medicine. 17 (7): 867–74. doi:10.1038/nm.2379. PMC 4020577. PMID 21706029.

- Esposito, I; Penzel, R; Chaib-Harrireche, M; Barcena, U; Bergmann, F; Riedl, S; Kayed, H; Giese, N; et al. (2006). "Tenascin C and annexin II expression in the process of pancreatic carcinogenesis". The Journal of Pathology. 208 (5): 673–85. doi:10.1002/path.1935. PMID 16450333.

- Kaneishi, Nelson K.; Cockerell, Clay J. (1998). "Histologic Differentiation of Desmoplastic Melanoma from Cicatrices". The American Journal of Dermatopathology. 20 (2): 128–34. doi:10.1097/00000372-199804000-00004. PMID 9557779.

- Walker, Rosemary A (2001). "The complexities of breast cancer desmoplasia". Breast Cancer Research. 3 (3): 143–5. doi:10.1186/bcr287. PMC 138677. PMID 11305947.