Dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a deficit of total body water,[1] with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake, usually due to exercise, disease, or high environmental temperature. Mild dehydration can also be caused by immersion diuresis, which may increase risk of decompression sickness in divers.

| Dehydration | |

|---|---|

| |

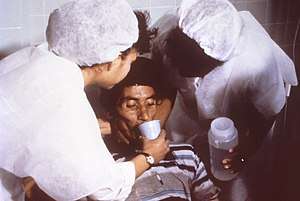

| Nurses encourage a patient to drink an oral rehydration solution to reduce the combination of dehydration and hypovolemia he acquired from cholera. Cholera leads to GI loss of both excess free water (dehydration) and sodium (hence ECF volume depletion—hypovolemia). | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine |

Most people can tolerate a 3-4% decrease in total body water without difficulty or adverse health effects. A 5-8% decrease can cause fatigue and dizziness. Loss of over ten percent of total body water can cause physical and mental deterioration, accompanied by severe thirst. Death occurs at a loss of between fifteen and twenty-five percent of the body water.[2] Mild dehydration is characterized by thirst and general discomfort and is usually resolved with oral rehydration.

Dehydration can cause hypernatremia (high levels of sodium ions in the blood) and is distinct from hypovolemia (loss of blood volume, particularly blood plasma).

Signs and symptoms

The hallmarks of dehydration include thirst and neurological changes such as headaches, general discomfort, loss of appetite, decreased urine volume (unless polyuria is the cause of dehydration), confusion, unexplained tiredness, purple fingernails and seizures. The symptoms of dehydration become increasingly severe with greater total body water loss. A body water loss of 1-2%, considered mild dehydration, is shown to impair cognitive performance.[4] In people over age 50, the body's thirst sensation diminishes and continues diminishing with age. Many senior citizens suffer symptoms of dehydration. Dehydration contributes to morbidity in the elderly population, especially during conditions that promote insensible free water losses, such as hot weather. A Cochrane review on this subject defined water-loss dehydration as "people with serum osmolality of 295 mOsm/kg or more" and found that the main symptom in the elderly (people aged over 65) was fatigue.[5]

Cause

Risk factors for dehydration include but are not limited to: exerting oneself in hot and humid weather, habitation at high altitudes, endurance athletics, elderly adults, infants, children and people living with chronic illnesses.[6]

Dehydration can also come as a side effect from many different types of drugs and medications.[7]

In the elderly, blunted response to thirst or inadequate ability to access free water in the face of excess free water losses (especially hyperglycemia related) seem to be the main causes of dehydration.[8] Excess free water or hypotonic water can leave the body in two ways – sensible loss such as osmotic diuresis, sweating, vomiting and diarrhea, and insensible water loss, occurring mainly through the skin and respiratory tract. In humans, dehydration can be caused by a wide range of diseases and states that impair water homeostasis in the body. These occur primarily through either impaired thirst/water access or sodium excess.[9]

Diagnosis

Definition

Dehydration occurs when water intake is not enough to replace free water lost due to normal physiologic processes, including breathing, urination, and perspiration, or other causes, including diarrhea and vomiting. Dehydration can be life-threatening when severe and lead to seizures or respiratory arrest, and also carries the risk of osmotic cerebral edema if rehydration is overly rapid.[10]

The term "dehydration" itself has sometimes been used incorrectly as a proxy for the separate, related condition hypovolemia, which specifically refers to a decrease in volume of blood plasma.[1] The two are regulated through independent mechanisms in humans;[1] the distinction is important in guiding treatment.[11]

Prevention

For routine activities, thirst is normally an adequate guide to maintain proper hydration.[12] Minimum water intake will vary individually depending on weight, environment, diet and genetics.[13] With exercise, exposure to hot environments, or a decreased thirst response, additional water may be required. In athletes in competition drinking to thirst optimizes performance and safety, despite weight loss, and as of 2010, there was no scientific study showing that it is beneficial to stay ahead of thirst and maintain weight during exercise.[14]

In warm or humid weather or during heavy exertion, water loss can increase markedly, because humans have a large and widely variable capacity for the active secretion of sweat. Whole-body sweat losses in men can exceed 2 L/h during competitive sport, with rates of 3–4 L/h observed during short-duration, high-intensity exercise in the heat.[15] When such large amounts of water are being lost through perspiration, electrolytes, especially sodium, are also being lost.

In most athletes, exercising and sweating for 4–5 hours with a sweat sodium concentration of less than 50 mmol/L, the total sodium lost is less than 10% of total body stores (total stores are approximately 2,500 mmol, or 58 g for a 70-kg person).[16] These losses appear to be well tolerated by most people. The inclusion of some sodium in fluid replacement drinks has some theoretical benefits[16] and poses little or no risk, so long as these fluids are hypotonic (since the mainstay of dehydration prevention is the replacement of free water losses).

Treatment

The treatment for minor dehydration that is often considered the most effective is drinking water and stopping fluid loss. Plain water restores only the volume of the blood plasma, inhibiting the thirst mechanism before solute levels can be replenished.[17] Solid foods can contribute to fluid loss from vomiting and diarrhea.[18] Urine concentration and frequency will customarily return to normal as dehydration resolves.[19]

In some cases, correction of a dehydrated state is accomplished by the replenishment of necessary water and electrolytes (through oral rehydration therapy or fluid replacement by intravenous therapy). As oral rehydration is less painful, non invasive, inexpensive and easier to provide, it is the treatment of choice for mild dehydration. Solutions used for intravenous rehydration must be isotonic or hypertonic. Pure water injected into the veins will cause the breakdown (lysis) of red blood cells (erythrocytes).

When fresh water is unavailable (e.g. at sea or in a desert), seawater or drinks with significant alcohol concentration will worsen the condition. Urine contains a lower solute concentration than seawater. This requires the kidneys to create more urine to remove the excess salt, causing more water to be lost than was consumed from seawater.[20] If somebody is dehydrated and is taken to a medical facility, IVs can also be used.[21][22][23][24]

For severe cases of dehydration where fainting, unconsciousness, or other severely inhibiting symptom is present (the patient is incapable of standing or thinking clearly), emergency attention is required. Fluids containing a proper balance of replacement electrolytes are given orally or intravenously with continuing assessment of electrolyte status; complete resolution is the norm in all but the most extreme cases.[25]

See also

- Hydrational fluids

- Terminal dehydration

- Dryness (medical)

- Oral Rehydration Therapy

References

- Mange K, Matsuura D, Cizman B, Soto H, Ziyadeh FN, Goldfarb S, Neilson EG (November 1997). "Language guiding therapy: the case of dehydration versus volume depletion". Annals of Internal Medicine. 127 (9): 848–53. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00020. PMID 9382413.

- Ashcroft F, Life Without Water in Life at the Extremes. Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2000, 134-138.

- "UOTW #59 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. September 23, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- Riebl SK, Davy BM (November 2013). "The Hydration Equation: Update on Water Balance and Cognitive Performance". ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal. 17 (6): 21–28. doi:10.1249/FIT.0b013e3182a9570f (inactive January 22, 2020). PMC 4207053. PMID 25346594.

- Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Attreed NJ, Campbell WW, Channell AM, Chassagne P, et al. (April 2015). "Clinical symptoms, signs and tests for identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD009647. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009647.pub2. hdl:2066/110560. PMID 25924806.

- "Dehydration Risk factors - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- https://www.webmd.com/drug-medication/medicines-can-cause-dehydration

- Borra SI, Beredo R, Kleinfeld M (March 1995). "Hypernatremia in the aging: causes, manifestations, and outcome". Journal of the National Medical Association. 87 (3): 220–4. PMC 2607819. PMID 7731073.

- Lindner G, Funk GC (April 2013). "Hypernatremia in critically ill patients". Journal of Critical Care. 28 (2): 216.e11–20. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.05.001. PMID 22762930.

- Dehydration at eMedicine

- Bhave G, Neilson EG (August 2011). "Volume depletion versus dehydration: how understanding the difference can guide therapy". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 58 (2): 302–9. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.02.395. PMC 4096820. PMID 21705120.

- "Dietary Reference Intakes: Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate : Health and Medicine Division". www.nationalacademies.org. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- Godman H (September 2016). "How much water should you drink?". Harvard Health. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- Noakes TD (2010). "Is drinking to thirst optimum?". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 57 Suppl 2 (s2): 9–17. doi:10.1159/000322697. PMID 21346332.

- Taylor NA, Machado-Moreira CA (February 2013). "Regional variations in transepidermal water loss, eccrine sweat gland density, sweat secretion rates and electrolyte composition in resting and exercising humans". Extreme Physiology & Medicine. 2 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/2046-7648-2-4. PMC 3710196. PMID 23849497.

- Coyle EF (January 2004). "Fluid and fuel intake during exercise". Journal of Sports Sciences. 22 (1): 39–55. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.321.6991. doi:10.1080/0264041031000140545. PMID 14971432.

- Murray R, Stofan J (2001). "Ch. 8: Formulating carbohydrate-electrolyte drinks for optimal efficacy". In Maughan RJ, Murray R (eds.). Sports Drinks: Basic Science and Practical Aspects. CRC Press. pp. 197–224. ISBN 978-0-8493-7008-3.

- "Healthwise Handbook," Healthwise, Inc. 1999

- Wedro B. "Dehydration". MedicineNet. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- "Can Humans drink seawater?". National Ocean Service. National Ocean Service NOAA Department of Commerce.

- SimpleSurvival Find Water

- Tracker Trail - Mother Earth News - Issue #72

- EQUIPPED TO SURVIVE (tm) - A Survival Primer

- "Five Basic Survival Skills in the Wilderness". Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- Ellershaw JE, Sutcliffe JM, Saunders CM (April 1995). "Dehydration and the dying patient". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 10 (3): 192–7. doi:10.1016/0885-3924(94)00123-3. PMID 7629413.

Further reading

- Byock I (1995). "Patient refusal of nutrition and hydration: walking the ever-finer line". The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 12 (2): 8–13. doi:10.1177/104990919501200205. PMID 7605733.

- Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS (June 2004). "Is this child dehydrated?". JAMA. 291 (22): 2746–54. doi:10.1001/jama.291.22.2746. PMID 15187057.

External links

| Look up dehydration in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |