Debar

Debar (Macedonian: Дебaр [ˈdɛbar] (![]()

Debar | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Debar with Debar Lake to the left | |

Seal | |

Debar Location within North Macedonia | |

| Coordinates: 41°31′N 20°32′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| Municipality | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Hekuran Duka |

| Population (2002) | |

| • Total | 14,561 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 1250 |

| Climate | Cfb |

| Website | Official Website |

Name

The name of the city in Macedonian is Debar (Дебар). In Albanian; Dibër/Dibra or Dibra e Madhe (meaning "Great Dibra", in contrast to the other Dibër in Albania). In Serbian Debar (Дебар), in Bulgarian Debǎr (Дебър), in Turkish Debre or Debre-i Bala, in Greek, Dívrē (Δίβρη) or Dívra (Δίβρα), in Ancient Greek Dèvoros, Δήβορος and in Roman times as Deborus.[2]

Geography

Debar is surrounded by the Dešat, Stogovo, Jablanica and Bistra mountains.

It is located 625 meters above sea level, next to Lake Debar, the Black Drin River and its smaller break-off river, Radika.

Population

According to the last census data from 2002, the city of Debar has a population of 14,561, made up of

- 10,768 (74.0%) Albanians,

- 1,415 (9.7%) Turks,

- 1,079 (7.2%) Romani,

- 1,054 (7.2%) Macedonians, and

- 245 (1.7%) others.[3]

| Ethnic group |

census 1948 | census 1953 | census 1961 | census 1971 | census 1981 | census 1994 | census 2002 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Albanians | .. | .. | 4,122 | 74.7 | 4,507 | 71.3 | 6,681 | 75.7 | 8,625 | 70.7 | 9,400 | 70.5 | 10,768 | 74.0 |

| Turks | .. | .. | 53 | 1.0 | 195 | 3.1 | 367 | 4.2 | 573 | 4.7 | 1,175 | 8.8 | 1,415 | 9.7 |

| Romani | .. | .. | 83 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,030 | 8.5 | 1,103 | 8.3 | 1,079 | 7.4 |

| Macedonians | .. | .. | 1,110 | 20.1 | 1,009 | 16.0 | 1,276 | 14.5 | 1,106 | 9.1 | 1,431 | 10.7 | 1,054 | 7.3 |

| Vlachs | .. | .. | 2 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.0 |

| Serbs | .. | .. | 87 | 1.6 | 57 | 0.9 | 105 | 1.2 | 37 | 0.3 | 34 | 0.3 | 22 | 0.2 |

| Bosniaks | .. | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.0 |

| Others | .. | .. | 63 | 1.2 | 555 | 8.8 | 394 | 4.5 | 830 | 6.8 | 196 | 1.5 | 219 | 1.5 |

| Total | 4,698 | 5,520 | 6,323 | 8,823 | 12,201 | 13,340 | 14,561 | |||||||

History

The earliest recording of Debar is under the name of ‘Deborus’ on a map drawn by the astronomer and cartographer Ptolemy in the 2nd century.[5]

The Byzantine emperor Basil II knew of its existence, and Felix Petancic referred to it as Dibri in 1502.[5]

After Samuel of Bulgaria was defeated in 1014 by Byzantine emperor Basil II, Debar was administered under the Bishopric of Bitola.

In the latter half of the 14 century Debar was ruled by the Albanian Kastrioti clan, but fell under the rule of the Ottoman Empire when local Albanian ruler Gjon Kastrioti died shortly after his four children were taken hostage.[5]

It was conquered by the Ottomans in 1395 and subsequently became the seat of the Sanjak of Dibra.

In 1440 Skanderbeg was appointed as its sanjakbey.[6][7]

Gjergj Kastrioti, survived to take back his father's land and untie all of Albania in 1444. A larger than life size statue of Skenderbeg adorns Debar's centre, showing the fondness that the locals have for his cause. During the Ottoman-Albanian wars between 1443-1479 the Debar region was the borderline between the Ottomans and the League of Lezhë led by Skanderbeg and became an area of continuous conflict. There were two major battles near Debar, on June 29, 1444 and on September 27, 1446, both ending with the defeat of the Ottoman armies.

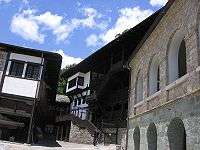

Debar was overrun once again by the Turks, and became known as Debre. The city constantly rebelled against Turkish rule, however, not least because of the wealth of the many Turkish bey and aga who lived there off local taxes and the fat of the land.[5] Turkish rule also brought trade to Debar and the city centre grew and became known for its crafts industry.[5] Much of the architect from that period still survives.

In the early 19th century, when Debar rebelled against the Turkish Sultan, the French traveller, publicist, and scientist Ami Boue observed that Debar had 64 shops and 4,200 residents. It was first a sanjak centre in Scutari Vilayet before 1877, and afterwards in Manastir Vilayet between 1877-1912 as Debre or Debre-i Bala ("Upper Debre" in Ottoman Turkish, as contrasted with Debre-i Zir, which was Peshkopi's Turkish name).

In the late Ottoman period, Debre (Debar) was a town with 20,000 inhabitants, 420 shops, 9 mosques, 10 madrasas, 5 tekkes, 11 government run primary schools, 1 secondary school, 3 Christian primary schools and 1 church.[8] An Ottoman army division was also stationed within the town.[8]

Debar was significantly involved in the national Albanian movement and on November 1, 1878 the Albanian leaders of the city participated in founding the League of Prizren.

In 1907 the Congress of Dibra was held in the town, which made Albanian an official language within the Ottoman Empire. The congress allowed that Albanian be taught in schools legally for the first time within the Empire.[9]

Following the capture of the town of Debar by Serbia, many of its Albanian inhabitants fled to Turkey, the rest went to Tirana.[10] Of those that ended up in Istanbul, some of their number migrated to Albania, mainly to Tirana where the Dibran community formed an important segment of the capital city's population from 1920 onward and for some years thereafter.[10]

During the Balkan wars of 1912 – 13 Debar was taken back by the Albanians, but was then handed over to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes as a reward for helping the Allies during World War I.[5] Thereafter many Serbs and Montenegrins were encouraged to settle in Debar, a common tactic to ensure that newly acquired land became more integrated with the motherland.[5]

It was occupied by Kingdom of Bulgaria between 1915 and 1918.

From 1929 to 1941, Debar was part of the Vardar Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Debar was annexed, along with most of Western North Macedonia, into the Italian-controlled Kingdom of Albania on 17 April 1941, following the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia during the Second World War. Greater Albania was officially a protectorate of Italy and therefore public administration duties were passed to Albanian authorities. Albanian-language schools, radio stations and newspapers were established in Debar. When Italy capitulated in September 1943, Debar passed into German hands. In 1944, after a two-month struggle for the city between the communist Albanian National Liberation Front and German forces holding the city, including the SS Skanderbeg division, the communists led by Haxhi Lleshi finally secured Debar on August 30, 1944.[11]

After the cessation of hostilities with the end of WW2 and the establishment of communism in both Albania and Yugoslavia, Debar passed back into Yugoslav hands.

Culture

Some of the best craftsman, woodcarving masters and builders came from the Debar region and were recognized for their skills in creating detailed and impressive woodcarvings, painting beautiful icons and building unique architecture. In fact, Debar was one of the then famous three woodcarving schools in the region, the other two being Samokov and Bansko. Their work can be seen in many churches and cultural buildings throughout the Balkan Peninsula. The Mijak School of woodcarving became noted for its artistic excellence, and an amazing example that can be seen today by tourists is the iconostasis in the nearby Monastery of Saint Jovan Bigorski, near the town of Debar.[12] The monastery was rebuilt in the 19th century and is situated on the slopes of Mount Bistra, above the banks of the River Radika. The monastery was built on the remains of an older church dating from 1021.

Another important religious monument is the monastery of Saint Gjorgi in the village of Rajcica in the immediate vicinity of Debar. The monastery was recently built.

Grigor Parlichev was given the title Second Homer in 1860 in Athens for his poem The Serdar. Based on a folk poem, it deals with the exploits and heroic death of Kuzman Kapidan, a famous hero and protector of Christian people in the Debar region in their struggle with bandits.

Some of the oldest and richest Albanian epics still exist in the Debar regions and are part of the Albanian mythological heritage.

Debar is also known for its pizza consumption. As of 2018, Debar had one pizzeria for every 3,000 residents, and emigrants from the town had opened approximately 50 pizza restaurants in the United States.[13]

Sports

Local football club Korabi plays in the Macedonian Second League (West Division).

Notable people from Debar

- Gjon Kastrioti, father of Skanderbeg

- Nexhat Agolli, politician and deputy president of ASNOM

- Eqrem Basha, writer

- Abdurraman Dibra, politician, minister in Ahmet Zogu's rule

- Fiqri Dine, former prime minister of Albania

- Akif Erdemgil, military officer in the Ottoman and Turkish armies

- Moisi Golemi, general in Skenderbeg's army

- John of Debar, Orthodox clergyman

- Sherif Lengu, a founding father of modern Albania

- Haki Stërmilli, writer

- Myfti Vehbi Dibra Agolli, modern Albania founding father

References

- "Debar (Municipality, North Macedonia)". www.crwflags.com.

- Stephano, Carolo. Dictionarium historicum, geographicum, poeticum. p. 783.

- Macedonian Census (2002), Book 5 - Total population according to the Ethnic Affiliation, Mother Tongue and Religion, The State Statistical Office, Skopje, 2002, p. 89.

- Censuses of population 1948 - 2002 Archived October 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Evans, Thammy (2014). Macedonia. Bradt Travel Guides Ltd, IDC House, The Vale, Chalfront St Peter, Bucks SL9 9RZ, England: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. p. 260. ISBN 978 1 84162 395 5. Retrieved 2015-12-31.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Zhelyazkova, Antonina. "Albanian identities". Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

In 1440, he was promoted to sancakbey of Debar

- Hösch, Peter (1972). The Balkans: a short history from Greek times to the present day, Volume 1972, Part 2. Crane, Russak. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8448-0072-1. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. pp. 35-36. ISBN 9781845112875.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Torte, Rexhep (4 August 2009). "Përfundoi shënimi i 100-vjetorit të Kongresit të Dibrës". Albaniapress.

- Clayer, Nathalie (2005). "The Albanian students of the Mekteb-i Mülkiye: Social networks and trends of thought". In Özdalga, Elisabeth (ed.). Late Ottoman Society: The Intellectual Legacy. Routledge. pp. 306–307. ISBN 9780415341646.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Magaš, Branka (1993). The destruction of Yugoslavia: tracking the break-up 1980-92. Verso. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-86091-593-5. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- Janko Petrovski; Aleksandar Dautovski; Angelikija Anakijeva (2004). Undying creativity: a pictorial journey through Macedonia. MacedoniaDirect. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-9989-2343-0-9.

- Feldman, Amy. "Pizza Unchained: Tech Startup Slice Helps Local Pizzerias Get Online And Fight Back Against Domino's". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2018-04-12. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

General references

- The History of Byzantine State by G. Ostrogorsky

- The Serdar by G. Prlicev