Deborah Read

Deborah Read Franklin (c. 1708 – December 19, 1774) was the common-law wife of Benjamin Franklin, polymath and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States.

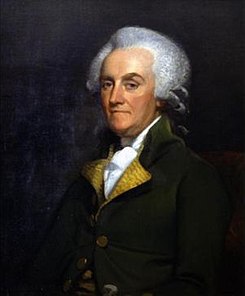

Deborah Read | |

|---|---|

Deborah Read Franklin, portrait attributed to Benjamin Wilson | |

| Born | c. 1708 Birmingham, England |

| Died | December 19, 1774 (aged 66) |

| Resting place | Christ Church Burial Ground |

| Other names | Deborah Read Rogers Deborah Read Franklin |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Francis Folger Franklin Sarah Franklin Bache |

Early years

Little is known about Read's early life. She was born around 1708, most likely in Birmingham, England (Some sources state she was born in Philadelphia)[1] to John and Sarah Read, a well respected Quaker couple. John Read was a moderately prosperous building contractor and carpenter who died in 1724. Read had three siblings: two brothers, John and James, and a sister, Frances.[2] The Read family immigrated to English America in 1711, settling in Philadelphia.[3]

Marriages

In October 1723, Read met then 17-year-old Benjamin Franklin when he walked past the Read home on Market Street one morning.[2] Franklin had just moved to Philadelphia from Boston to find employment as a printer. In his autobiography, Franklin recalled that at the time of their meeting, he was walking while carrying "three great puffy rolls".[4] As he had no pockets, Franklin carried one roll under each arm and was eating the third. Read (whom Franklin called "Debby") was standing in the doorway of her home and was amused by the sight of Franklin's "most awkward ridiculous appearance."[2][4] A romance between Read and Franklin soon developed. When Franklin was unable to find appropriate living accommodations near his job, Read's father allowed him to rent a room in the family home.[4] Read and Franklin's courtship continued, and in 1724, Franklin proposed marriage. However, Read's mother, Mary, would not consent to the marriage, citing Franklin's pending trip to London and financial instability.[4] Read and Franklin postponed their marriage plans and Franklin traveled to England. Upon arriving in London, Franklin decided to end the relationship. In a terse letter, he informed Read that he had no intention of returning to Philadelphia. Franklin subsequently became stranded in London after Sir William Keith failed to follow through on promises of financial support.[5][6]

In Franklin's absence, Read was persuaded by her mother to marry John Rogers, a British man who has been identified variously as a carpenter or a potter.[2][7] Read eventually agreed and married Rogers on August 5, 1725 at Christ Church, Philadelphia.[2] The marriage quickly fell apart as the "sweet-talking" Rogers could not hold a job and had incurred a large amount of debt before their marriage. Four months after they were married, Read left Rogers after a friend of Rogers’ visiting from England informed her that Rogers had a wife in his native England.[8] Read refused to live with or recognize Rogers as her husband.[2] While the couple were separated, Rogers spent Read's dowry, incurred more debt, and used the marriage to further his own schemes. In December 1727, Rogers stole a slave and disappeared.[9] Soon afterward, unconfirmed reports circulated that Rogers had made his way to the British West Indies, where he was killed in a fight.[8][9] In his autobiography, Franklin also claimed that Rogers died in the British West Indies.[10] John Rogers' true fate has never been proven.[11]

Despite his previous intention to remain in London, Franklin returned to Philadelphia in October 1727. He and Read eventually resumed their relationship and decided to marry. While Read considered her marriage to her first husband to be over, she was not able to legally remarry. At that time, the law in the Province of Pennsylvania would not grant a divorce on the grounds of desertion. She could neither claim to be a widow, as there was no proof that Rogers was dead. If Rogers returned after Read legally married Franklin, she faced a charge of bigamy which carried the penalty of thirty nine lashings on the bare back and life imprisonment with hard labor.[12] To avoid any legal issues, Read and Franklin decided upon a common-law marriage. On September 1, 1730, the couple held a ceremony for friends and family in which they announced they would live as husband and wife.[13] They had two children together: Francis Folger "Franky" (born 1732), who died of smallpox in 1736 at the age of four, and Sarah "Sally" (born 1743). Reed also helped to raise Franklin's illegitimate son William, whose mother's identity is unknown.[14]

Later years and death

By the late 1750s, Benjamin Franklin had established himself as a successful printer, publisher, and writer. He was appointed the first postmaster of Philadelphia and was heavily involved in social and political affairs that would eventually lead to the establishment of the United States. In 1757, Franklin embarked on the first of numerous trips to Europe. Read refused to accompany him due to a fear of ocean travel. While Franklin stayed overseas for the next five years, Read remained in Philadelphia where, despite her limited education, she successfully ran her husband's businesses, maintained their home, cared for the couple's children and regularly attended Quaker Meeting.[15][16]

Franklin returned to Philadelphia in November 1762. He tried to persuade Read to accompany him to Europe, but she again refused. Franklin returned to Europe in November 1764 where he would remain for the next ten years.[17] Read would never see Franklin again.[15]

In 1768, Read suffered the first of a series of strokes that severely impaired her speech and memory. For the remainder of her life, she suffered from poor health and depression. Despite his wife's condition, Franklin did not return to Philadelphia even though he had completed his diplomatic duties.[18] In November 1769, Read wrote Franklin saying that her stroke, declining health and depressed mental state were a result of her "dissatisfied distress" due to his prolonged absence.[19] Franklin still did not return but continued to write to Read. Read's final surviving letter to Franklin is dated October 29, 1773. Thereafter, she stopped corresponding with her husband. Franklin continued to write to Read, inquiring as to why her letters had ceased, but still did not return home.[18]

On December 14, 1774, Read suffered a final stroke and died on December 19. She was buried at Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia. Franklin was buried next to her upon his death in 1790.[20]

Francis Folger Franklin

Francis Folger Franklin Sarah [Franklin] Bache

Sarah [Franklin] Bache William Franklin

William Franklin

References

- (Appleby, Chang, Goowin 2015, p. 102)

- (McKenney 2013, p. 68)

- (Chandler Waldrup 2004, p. 44)

- (Chandler Waldrup 2004, p. 45)

- (Chandler Waldrup 2004, p. 46)

- (Franklin, Larabee, Ketcham 2003, pp. 94-95)

- (E. James, Wilson James, Boyer 1971, p. 663)

- (Mihalik Higgins 2007, p. 30)

- (Lemay 2013, p. 8)

- (Franklin, Larabee, Ketcham 2003, p. 107)

- (Marcovitz 2009, p. 49)

- (Marcovitz 2009, pp. 48-49)

- (Lemay 2013, pp. 7-8)

- (Lemay 2013, p. 7)

- (McKenney 2013, p. 69)

- (Chandler Waldrup 2004, p. 48)

- (Chandler Waldrup 2004, pp. 49-50)

- (Finger 2012, pp. 99-100)

- "Letter from Deborah Franklin dated November the 20[-27] 1769". Franklin Papers. franklinpapers.org. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- (Lemay 2013, p. 70)

Sources

- Appleby, Joyce; Chang, Eileen; Goodwin, Neva (2015). Encyclopedia of Women in American History. Routledge. ISBN 1-317-47162-8.

- Chandler Waldrup, Carole (2004). More Colonial Women: 25 Pioneers of Early America. McFarland. ISBN 0-786-41839-7.

- Finger, Stanley (2012). Doctor Franklin's Medicine. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-812-20191-4.

- Franklin, Benjamin (April 19, 2003). Labaree, Leonard W.; Ketcham, Ralph L. (eds.). The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (2 ed.). Yale Nota Bene. pp. 94–95. ISBN 0-300-09858-8.

- James, Edward T.; Wilson James, Janet; Boyer, Paul S., eds. (1971). Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 3. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-62734-2.

- Lemay, J. A. Leo (2013). The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 2: Printer and publisher, 1730-1747. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-812-20929-X.

- Marcovitz, Hal (2009). Benjamin Franklin. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1-438-10401-4.

- McKenney, Janice E. (2013). Women of the Constitution: Wives of the Signers. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-810-88498-4.

- Mihalik Higgins, Maria (2007). Benjamin Franklin: Revolutionary Inventor. Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 1-402-74952-X.

External links

- Benjamin Franklin FAQ from the Franklin Institute

- Deborah Reed Franklin from History of American Women

- Deborah Read at Find a Grave