Day trading

Day trading is speculation in securities, specifically buying and selling financial instruments within the same trading day, such that all positions are closed before the market closes for the trading day. Traders who trade in this capacity with the motive of profit are therefore speculators. The methods of quick trading contrast with the long-term trades underlying buy and hold and value investing strategies. Day traders exit positions before the market closes to avoid unmanageable risks and negative price gaps between one day's close and the next day's price at the open.

Day traders generally use margin leverage; in the United States, Regulation T permits an initial maximum leverage of 2:1, but many brokers will permit 4:1 leverage as long as the leverage is reduced to 2:1 or less by the end of the trading day. In the United States, people who make more than 3 day trades per week are termed pattern day traders and are required to maintain $25,000 in equity in their accounts.[1] Since margin interest is typically only charged on overnight balances, the trader may pay no interest fees for the margin benefit, though still running the risk of a margin call. Margin interest rates are usually based on the broker's call.

Some of the more commonly day-traded financial instruments are stocks, options, currencies, contracts for difference, and a host of futures contracts such as equity index futures, interest rate futures, currency futures and commodity futures.

Day trading was once an activity that was exclusive to financial firms and professional speculators. Many day traders are bank or investment firm employees working as specialists in equity investment and fund management. Day trading gained popularity after the deregulation of commissions in the United States in 1975, the advent of electronic trading platforms in the 1990s, and with the stock price volatility during the dot-com bubble.[2]

Some day traders use an intra-day technique known as scalping that usually has the trader holding a position for a few minutes or only seconds.

Profit and risks

Because of the nature of financial leverage and the rapid returns that are possible, day trading results can range from extremely profitable to extremely unprofitable, and high-risk profile traders can generate either huge percentage returns or huge percentage losses.[3]

Because of the high profits (and losses) that day trading makes possible, these traders are sometimes portrayed as "bandits" or "gamblers" by other investors.

Day trading is risky, especially if any of the following is present while trading:

- trading a loser's game/system rather than a game that's at least winnable,[4]

- inadequate risk capital with the accompanying excess stress of having to "survive",

- incompetent money management (i.e. executing trades poorly).[5][6]

The common use of buying on margin (using borrowed funds) amplifies gains and losses, such that substantial losses or gains can occur in a very short period of time. In addition, brokers usually allow bigger margin for day traders. In the United States for example, while the initial margin required to hold a stock position overnight are 50% of the stock's value due to Regulation T, many brokers allow pattern day trader accounts to use levels as low as 25% for intraday purchases. This means a day trader with the legal minimum $25,000 in their account can buy $100,000 (4x leverage) worth of stock during the day, as long as half of those positions are exited before the market close. Because of the high risk of margin use, and of other day trading practices, a day trader will often have to exit a losing position very quickly, in order to prevent a greater, unacceptable loss, or even a disastrous loss, much larger than their original investment, or even larger than their total assets.

History

Originally, the most important U.S. stocks were traded on the New York Stock Exchange. A trader would contact a stockbroker, who would relay the order to a specialist on the floor of the NYSE. These specialists would each make markets in only a handful of stocks. The specialist would match the purchaser with another broker's seller; write up physical tickets that, once processed, would effectively transfer the stock; and relay the information back to both brokers. Before 1975, brokerage commissions were fixed at 1% of the amount of the trade, i.e. to purchase $10,000 worth of stock cost the buyer $100 in commissions and same 1% to sell. Meaning that to profit trades had to make over 2 % to make any real gain.

One of the first steps to make day trading of shares potentially profitable was the change in the commission scheme. In 1975, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) made fixed commission rates illegal, giving rise to discount brokers offering much reduced commission rates.

Financial settlement

Financial settlement periods used to be much longer: Before the early 1990s at the London Stock Exchange, for example, stock could be paid for up to 10 working days after it was bought, allowing traders to buy (or sell) shares at the beginning of a settlement period only to sell (or buy) them before the end of the period hoping for a rise in price. This activity was identical to modern day trading, but for the longer duration of the settlement period. But today, to reduce market risk, the settlement period is typically two working days. Reducing the settlement period reduces the likelihood of default, but was impossible before the advent of electronic ownership transfer.

Electronic communication networks

The systems by which stocks are traded have also evolved, the second half of the twentieth century having seen the advent of electronic communication networks (ECNs). These are essentially large proprietary computer networks on which brokers can list a certain amount of securities to sell at a certain price (the asking price or "ask") or offer to buy a certain amount of securities at a certain price (the "bid").

ECNs and exchanges are usually known to traders by a three- or four-letter designators, which identify the ECN or exchange on Level II stock screens. The first of these was Instinet (or "inet"), which was founded in 1969 as a way for major institutions to bypass the increasingly cumbersome and expensive NYSE, and to allow them to trade during hours when the exchanges were closed.[7] Early ECNs such as Instinet were very unfriendly to small investors, because they tended to give large institutions better prices than were available to the public. This resulted in a fragmented and sometimes illiquid market.

The next important step in facilitating day trading was the founding in 1971 of NASDAQ—a virtual stock exchange on which orders were transmitted electronically. Moving from paper share certificates and written share registers to "dematerialized" shares, traders used computerized trading and registration that required not only extensive changes to legislation but also the development of the necessary technology: online and real time systems rather than batch; electronic communications rather than the postal service, telex or the physical shipment of computer tapes, and the development of secure cryptographic algorithms.

These developments heralded the appearance of "market makers": the NASDAQ equivalent of a NYSE specialist. A market maker has an inventory of stocks to buy and sell, and simultaneously offers to buy and sell the same stock. Obviously, it will offer to sell stock at a higher price than the price at which it offers to buy. This difference is known as the "spread". The market maker is indifferent as to whether the stock goes up or down, it simply tries to constantly buy for less than it sells. A persistent trend in one direction will result in a loss for the market maker, but the strategy is overall positive (otherwise they would exit the business). Today there are about 500 firms who participate as market makers on ECNs, each generally making a market in four to forty different stocks. Without any legal obligations, market makers were free to offer smaller spreads on electronic communication networks than on the NASDAQ. A small investor might have to pay a $0.25 spread (e.g. he might have to pay $10.50 to buy a share of stock but could only get $10.25 for selling it), while an institution would only pay a $0.05 spread (buying at $10.40 and selling at $10.35).

SOES

Following the 1987 stock market crash, the SEC adopted "Order Handling Rules" which required market makers to publish their best bid and ask on the NASDAQ.[8] Another reform made was the "Small-order execution system", or "SOES", which required market makers to buy or sell, immediately, small orders (up to 1000 shares) at the market maker's listed bid or ask. The design of the system gave rise to arbitrage by a small group of traders known as the "SOES bandits", who made sizable profits buying and selling small orders to market makers by anticipating price moves before they were reflected in the published inside bid/ask prices. The SOES system ultimately led to trading facilitated by software instead of market makers via ECNs.[9]

Before the bubble

In the late 1990s, existing ECNs began to offer their services to small investors. New ECNs arose, most importantly Archipelago (NYSE Arca) Instinet, SuperDot, and Island ECN. Archipelago eventually became a stock exchange and in 2005 was purchased by the NYSE.

Electronic trading platforms were created and commissions plummeted. An online trader in 2005 might have bought $300,000 worth of stock at a commission of less than $10, compared to the $3,000 commission the trader would have paid in 1974. Moreover, the trader was able in 2005 to buy the stock almost instantly and got it at a cheaper price.

This combination of factors has made day trading in stocks and stock derivatives (such as ETFs) possible. The low commission rates allow an individual or small firm to make a large number of trades during a single day. The liquidity and small spreads provided by ECNs allow an individual to make near-instantaneous trades and to get favorable pricing.

Technology bubble (1997–2000)

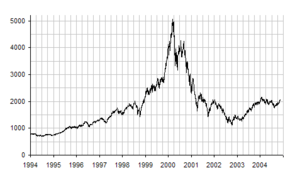

The ability for individuals to day trade coincided with the extreme bull market in technological issues from 1997 to early 2000, known as the dot-com bubble. From 1997 to 2000, the NASDAQ rose from 1200 to 5000. Many naive investors with little market experience made huge profits buying these stocks in the morning and selling them in the afternoon, at 400% margin rates.

In March 2000, this bubble burst, and a large number of less-experienced day traders began to lose money as fast, or faster, than they had made during the buying frenzy. The NASDAQ crashed from 5000 back to 1200; many of the less-experienced traders went broke, although obviously it was possible to have made a fortune during that time by short selling or playing on volatility.[10][11]

In parallel to stock trading, starting at the end of the 1990s, several new market maker firms provided foreign exchange and derivative day trading through electronic trading platforms. These allowed day traders to have instant access to decentralised markets such as forex and global markets through derivatives such as contracts for difference. Most of these firms were based in the UK and later in less restrictive jurisdictions, this was in part due to the regulations in the US prohibiting this type of over-the-counter trading. These firms typically provide trading on margin allowing day traders to take large position with relatively small capital, but with the associated increase in risk. The retail foreign exchange trading became popular to day trade due to its liquidity and the 24-hour nature of the market.

Techniques

The following are several basic trading strategies by which day traders attempt to make profits. In addition, some day traders also use contrarian investing strategies (more commonly seen in algorithmic trading) to trade specifically against irrational behavior from day traders using the approaches below. It is important for a trader to remain flexible and adjust techniques to match changing market conditions.[12]

Some of these approaches require short selling stocks; the trader borrows stock from his broker and sells the borrowed stock, hoping that the price will fall and he will be able to purchase the shares at a lower price, thus keeping the difference as their profit. There are several technical problems with short sales - the broker may not have shares to lend in a specific issue, the broker can call for the return of its shares at any time, and some restrictions are imposed in America by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission on short-selling (see uptick rule for details). Some of these restrictions (in particular the uptick rule) don't apply to trades of stocks that are actually shares of an exchange-traded fund (ETF).

Trend following

Trend following, a strategy used in all trading time-frames, assumes that financial instruments which have been rising steadily will continue to rise, and vice versa with falling. The trend follower buys an instrument which has been rising, or short sells a falling one, in the expectation that the trend will continue.

Contrarian investing

Contrarian investing is a market timing strategy used in all trading time-frames. It assumes that financial instruments that have been rising steadily will reverse and start to fall, and vice versa. The contrarian trader buys an instrument which has been falling, or short-sells a rising one, in the expectation that the trend will change.[13]

Range trading

Range trading, or range-bound trading, is a trading style in which stocks are watched that have either been rising off a support price or falling off a resistance price. That is, every time the stock hits a high, it falls back to the low, and vice versa. Such a stock is said to be "trading in a range", which is the opposite of trending.[14] The range trader therefore buys the stock at or near the low price, and sells (and possibly short sells) at the high. A related approach to range trading is looking for moves outside of an established range, called a breakout (price moves up) or a breakdown (price moves down), and assume that once the range has been broken prices will continue in that direction for some time.

Scalping

Scalping was originally referred to as spread trading. Scalping is a trading style where small price gaps created by the bid–ask spread are exploited by the speculator. It normally involves establishing and liquidating a position quickly, usually within minutes or even seconds.

Scalping highly liquid instruments for off-the-floor day traders involves taking quick profits while minimizing risk (loss exposure).[15] It applies technical analysis concepts such as over/under-bought, support and resistance zones as well as trendline, trading channel to enter the market at key points and take quick profits from small moves. The basic idea of scalping is to exploit the inefficiency of the market when volatility increases and the trading range expands. Scalpers also use the "fade" technique. When stock values suddenly rise, they short sell securities that seem overvalued.[16]

Rebate trading

Rebate trading is an equity trading style that uses ECN rebates as a primary source of profit and revenue. Most ECNs charge commissions to customers who want to have their orders filled immediately at the best prices available, but the ECNs pay commissions to buyers or sellers who "add liquidity" by placing limit orders that create "market-making" in a security. Rebate traders seek to make money from these rebates and will usually maximize their returns by trading low priced, high volume stocks. This enables them to trade more shares and contribute more liquidity with a set amount of capital, while limiting the risk that they will not be able to exit a position in the stock.[17]

News playing

The basic strategy of news playing is to buy a stock which has just announced good news, or short sell on bad news. Such events provide enormous volatility in a stock and therefore the greatest chance for quick profits (or losses). Determining whether news is "good" or "bad" must be determined by the price action of the stock, because the market reaction may not match the tone of the news itself. This is because rumors or estimates of the event (like those issued by market and industry analysts) will already have been circulated before the official release, causing prices to move in anticipation. The price movement caused by the official news will therefore be determined by how good the news is relative to the market's expectations, not how good it is in absolute terms.

Price action

Price action trading relies on technical analysis but does not rely on conventional indicators. These traders rely on a combination of price movement, chart patterns, volume, and other raw market data to gauge whether or not they should take a trade. This is seen as a "minimalist" approach to trading but is not by any means easier than any other trading methodology. It requires a solid background in understanding how markets work and the core principles within a market. However, the benefit for this methodology is that it is effective in virtually any market (stocks, foreign exchange, futures, gold, oil, etc.).

Artificial intelligence

It is estimated that more than 75% of stock trades in United States are generated by algorithmic trading or high-frequency trading. The increased use of algorithms and quantitative techniques has led to more competition and smaller profits.[18] Algorithmic trading is used by banks and hedge funds as well as retail traders. Retail traders can choose to buy a commercially available Automated trading systems or to develop their own automatic trading software.

Cost

Commission

Commissions for direct-access brokers are calculated based on volume. The more shares traded, the cheaper the commission. The average commission per trade is roughly $5 per round trip (getting in and out of a position). While a retail broker might charge $7 or more per trade regardless of the trade size, a typical direct-access broker may charge anywhere from $0.01 to $0.0002 per share traded (from $10 down to $.20 per 1000 shares), or $0.25 per futures contract. Although a scalper can cover such costs with even a minimal gain, an SEC study reported that up to 70% of day traders lost, after paying commissions.[4]

Spread

The numerical difference between the bid and ask prices is referred to as the bid–ask spread. Most worldwide markets operate on a bid-ask-based system.

The ask prices are immediate execution (market) prices for quick buyers (ask takers) while bid prices are for quick sellers (bid takers). If a trade is executed at quoted prices, closing the trade immediately without queuing would always cause a loss because the bid price is always less than the ask price at any point in time.

The bid–ask spread is two sides of the same coin. The spread can be viewed as trading bonuses or costs according to different parties and different strategies. On one hand, traders who do NOT wish to queue their order, instead paying the market price, pay the spreads (costs). On the other hand, traders who wish to queue and wait for execution receive the spreads (bonuses). Some day trading strategies attempt to capture the spread as additional, or even the only, profits for successful trades.[19]

Market data

Market data is necessary for day traders to be competitive. A real-time data feed requires paying fees to the respective stock exchanges, usually combined with the broker's charges; these fees are usually very low compared to the other costs of trading. The fees may be waived for promotional purposes or for customers meeting a minimum monthly volume of trades. Even a moderately active day trader can expect to meet these requirements, making the basic data feed essentially "free". In addition to the raw market data, some traders purchase more advanced data feeds that include historical data and features such as scanning large numbers of stocks in the live market for unusual activity. Complicated analysis and charting software are other popular additions. These types of systems can cost from tens to hundreds of dollars per month to access.[20]

Regulations and restrictions

Pattern day trader

In addition, in the United States, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority and SEC further restrict the entry by means of "pattern day trader" amendments. Pattern day trader is a term defined by the SEC to describe any trader who buys and sells a particular security in the same trading day (day trades), and does this four or more times in any five consecutive business day period. A pattern day trader is subject to special rules, the main rule being that in order to engage in pattern day trading in a margin account, the trader must maintain an equity balance of at least $25,000. It is important to note that this requirement is only for day traders using a margin account.[21]

Profitability

A 2019 research paper looked at the performance of individual day traders in the Brazilian equity futures market.[22] Based on trading records from 2012 to 2017, they conclude that day trading is almost uniformly unprofitable. According to their abstract:

We show that it is virtually impossible for individuals to compete with HFTs and day trade for a living, contrary to what course providers claim. We observe all individuals who began to day trade between 2013 and 2015 in the Brazilian equity futures market, the third in terms of volume in the world, and who persisted for at least 300 days: 97% of them lost money, only 0.4% earned more than a bank teller (US$54 per day), and the top individual earned only US$310 per day with great risk (a standard deviation of US$2,560). We find no evidence of learning by day trading.

See also

- Extended hours trading

- Financial instrument

- Fundamental analysis

- Futures market

- Scalping

- Stock market

- Trader

- Price discovery

Notes and references

- "Day-Trading Margin Requirements: Know the Rules". Financial Industry Regulatory Authority.

- Karger, Gunther (August 22, 1999). "Daytrading: Wall Street's latest, riskiest get-rich scheme". American City Business Journals.

- "Day Trading: An Introduction". Investopedia.

- Jesse Angelo (August 10, 1999). "Day Trading is a scam: Report". The New York Post.

- "U.S. government warning about the dangers of day trading".

- Gomez, Steve; Lindloff, Andy (2011). Change is the only Constant. IN: Lindzon, Howard; Pearlman, Philip; Ivanhoff, Ivaylo. The StockTwits Edge: 40 Actionable Trade Set-Ups from Real Market Pros. Wiley Trading. ISBN 978-1118029053.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Instinet - A Nomura Company | History". www.instinet.com. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- CNBC, Scott Patterson, |Special to (2010-09-13). "Man Vs. Machine: How the Crash of '87 Gave Birth To High-Frequency Trading". www.cnbc.com. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- Goldfield, Robert (May 31, 1998). "Got $50,000 extra? Put it in day trading". American City Business Journals.

- Nakashima, David (February 11, 2002). "It's back to day jobs for most Internet 'day traders'". American City Business Journals.

- Hayes, Adam. "Dotcom Bubble Definition". Investopedia. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- Gomez, Steve (October 2009). "Adapting To Change". SFO Magazine. Retrieved 2013-10-17. (republished on Trader Planet, 2013)

- CHEN, JAMES (March 6, 2019). "Contrarian". Investopedia.

- CHEN, JAMES (May 4, 2018). "Trading Range". Investopedia.

- Norris, Emily. "Scalping: Small Quick Profits Can Add Up". Investopedia. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- "Type of Day Trader". DayTradeTheWorld.

- Blodget, Henry (May 4, 2018). "The Latest Wall Street Trading Scam That Costs You Billions". Business Insider.

- Duhigg, Charles (November 23, 2006). "Artificial intelligence applied heavily to picking stocks - Business - International Herald Tribune". The New York Times.

- Milton, Adam. "Large Bid and Ask Spreads in Day Trading Explained". The Balance. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- SETH, SHOBHIT (February 25, 2018). "Choosing the Right Day-Trading Software". Investopedia.

- "Day Traders: Mind Your Margin". Financial Industry Regulatory Authority.

- Chague, Fernando; De-Losso, Rodrigo; Giovannetti, Bruno. "Day Trading for a Living?". SSRN. SSRN 3423101.