Spanish fly

The Spanish fly (Lytta vesicatoria) is an emerald-green beetle in the blister beetle family (Meloidae). It and other such species were used in preparations offered by traditional apothecaries, often referred to as Cantharides or Spanish fly. The insect is the source of the terpenoid cantharidin, a toxic blistering agent once used as an aphrodisiac.

| Spanish fly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Family: | Meloidae |

| Genus: | Lytta |

| Species: | L. vesicatoria |

| Binomial name | |

| Lytta vesicatoria | |

L. vesicatoria is sometimes called Cantharis vesicatoria,[1] although the genus Cantharis is in an unrelated family, Cantharidae, the soldier beetles.[2]

Description and etymology

Lytta vesicatoria is a slender, soft-bodied metallic and iridescent golden-green insect, one of the blister beetles. It is approximately 5 mm (0.20 in) wide by 20 mm (0.79 in) long.[3][4][5][6]

The generic and specific names derive from the Greek λύττα (lytta) for martial rage, raging madness, Bacchic frenzy, or rabies,[7][8] and Latin vesica for blister.[9]

Range and habitat

The Spanish fly is a mainly southern European species[10][11] although its range of habitats is more completely described as being "throughout southern Europe and eastward to Central Asia and Siberia,"[3] alternatively as being throughout Europe, and parts of northern and southern Asia (excluding China).[12] It occurs locally in southern Great Britain[13] and Poland.[14]

Adult beetles primarily feed on leaves of ash, lilac, amur privet, honey suckle and white willow tree while occasionally being found on plum, rose, and elm.[3][15]

Life cycle

The defensive chemical cantharidin, for which the beetle is known, is produced only by males; females obtain it from males during mating, as the spermatophore contains some. This may be a nuptial gift, increasing the value of mating to the female, and thus increasing the male's reproductive fitness.[16]

The female lays her fertilised eggs on the ground, near the nest of a ground-nesting solitary bee. The larvae are very active as soon as they hatch. They climb a flowering plant and await the arrival of a solitary bee. They hook themselves on to the bee using the three claws on their legs that give the first instar larvae their name, triungulins (from Latin tri, three, and ungulus, claw). The bee carries the larvae back to its nest, where they feed on bee larvae and the bees' food supplies. The larvae are thus somewhere between predators and parasites. The active larvae moult into very different, more typically scarabaeoid larvae for the remaining two or more instars, in a development type called hypermetamorphosis. The adults emerge from the bees' nest and fly to the woody plants on which they feed.[17][3]

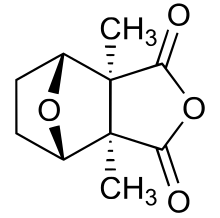

Cantharidin

Cantharidin, the principal active component in preparations of Spanish fly, was first isolated and named in 1810 by the French chemist Pierre Robiquet, who demonstrated that it was the principal agent responsible for the aggressively blistering properties of this insect's egg coating. It was asserted at that time that it was as toxic as the most violent poisons then known, such as strychnine.[18]

The active agent has been estimated present at about 0.2–0.7 mg per beetle, males producing significantly more than females. The beetle secretes the agent orally, and exudes it from its joints as a milky fluid. The potency of the insect species as a vesicant has been known since antiquity and the activity has been used in various ways. This has led to its small-scale commercial preparation and sale, in a powdered form known as cantharides (from the plural of Greek κανθαρίς, Kantharis, beetle), obtained from dried and ground beetles. The crushed powder is of yellow-brown to brown-olive color with iridescent reflections, is of disagreeable scent, and is bitter to taste. Cantharidin, the active agent, is a terpenoid, and is produced by some other insects, such as Epicauta immaculata.[4][1][19]

Cantharidin is dangerously toxic, inhibiting the enzyme phosphatase 2A. It causes irritation, blistering, bleeding and discomfort. These effects can escalate to erosion and bleeding of mucosa in each system, sometimes followed by severe gastro-intestinal bleeding and acute tubular necrosis and glomerular destruction, resulting in gastro-intestinal and renal dysfunction, by organ failure, and death.[19][20][21][22][23][20][24]

Preparations from L. vesicatoria and its active agent have been implicated in both inadvertent[19] and intentional poisonings.[19] Froberg notes a 1954 manslaughter case where cantharidin was administered in a coconut-flavoured candy as an intended aphrodisiac, resulting in illness and eventual death of two women (agent identified postmortem), and in facial blistering and criminal conviction of the perpetrator.[19]

Culinary uses

In Morocco and other parts of North Africa, spice blends known as ras el hanout sometimes included as a minor ingredient "green metallic beetles", inferred to be cantharides from L. vesicatoria, although sale of this in Moroccan spice markets was banned in the 1990s.[25] Dawamesk, a spread or jam made in North Africa and containing hashish, almond paste, pistachio nuts, sugar, orange or tamarind peel, cloves, and other various spices, occasionally included cantharides.[26]

Other uses

In ancient China, the beetles were mixed with human excrement, arsenic, and wolfsbane to make the world's first recorded stink bomb.[27]

Noteworthy cases

The Venezuelan leader Simón Bolívar may have been accidentally poisoned by application of Spanish fly.[28]

Arthur Kendrick Ford was convicted and given a multiyear prison sentence in 1954 for the unintended deaths of two women surreptitiously given candies laced with cantharidin, which were intended to act as an aphrodisiac.[19]

George Washington is thought to have been treated for epiglottitis (his cause of death)[29] with Spanish Fly. Of the many (now obsolete) treatments given to George Washington for his epiglottitis one of them involved Spanish Fly. Using it by blistering his throat with Spanish fly, a treatment that is no longer used.[30]

References

- Anon. (2012) [2009]. "Cantharide". Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary. Huntingdon Valley, PA, USA: Farlex. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Selander, Richardg B. (1991). "On the Nomenclature and Classification of Meloidae (Coleoptera)". Insecta Mundi. 5 (2): 65–94.

- Schlager, Neil, ed. (2004). "Coleoptera (beetles and weevils)". Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. vol. 3, Insects (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI, USA: Thomson-Gale/American Zoo and Aquarium Association. p. 331. ISBN 978-0787657796. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Aggrawal, Anil, ed. (2007). "VII. Spanish Fly (Cantharides)". APC Textbook of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology. New Delhi, India: Avichal. p. 652f. ISBN 978-8177394191. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Blood, Douglas Charles; Studdert, Virginia P.; Gay, Clive C., eds. (2007). "Cantharides". Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA, USA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0702027888. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Jonas, Wayne B., ed. (2005). "Cantharides". Mosby's Dictionary of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA, USA: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-0323025164. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "λύττα, λυττάω, λυττητικός, etc., v. λυσς-". Liddell & Scott. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "λύσσα". Liddell & Scott. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "vesico-, vesic-". English-Word Information. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Cutler, H.G. (1992). "An Historical Perspective of Ancient Poisons". In Nigg, H.G; D. Seigler (eds.). Phytochemical Resources for Medicine and Agriculture. p. 3. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-2584-8_1. ISBN 978-1-4899-2586-2.

- The Eds. of Encyclopædia Britannica (2015). "Blister beetle, insect". Encyclopædia Britannica (online). Chicago, IL, USA: Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Guala, Gerald, ed. (2015). "Geographic Information: Geographic Division". ITIS Report: Lytta vesicatoria (Linnaeus, 1758), Taxonomic Serial No.: 114404. Reston, VA, USA: U.S. Geological Survey, Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- "Lytta vesicatoria (Linnaeus, 1758)". UK Beetle Recording. NERC- Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "Lytta (Lytta) vesicatoria vesicatoria Linnaeus, 1758". Polish Biodiversity Information Network (Krajowa Sieć Informacji o Bioróżnorodności). Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- Neligan, J.M. & R. Macnamara (1867). Medicines, their uses and mode of administration; including a complete conspectus of the three British Pharmacopoeias, an account of all the new remedies, and an Appendix of Formulae. Fanin & Company. p. 297.

- Boggs, Carol L. (1995). Leather, S. R.; Hardie, J. (eds.). Male Nuptial Gifts: Phenotypic Consequences and Evolutionary Implications (PDF). CRC Press. pp. 215–242.

- "Illustrated lecture notes on Tropical Medicine - Ectoparasites - Beetles". Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Robiquet, M (1810). "Expériences sur les cantharides". Annales de Chimie. 76: 302–322.

- Froberg, Blake A. (2010). "Animals". In Holstege, Christopher P.; Neer, Thomas; Saathoff, Gregory B.; Furbee, R. Brent (eds.). Criminal Poisoning: Clinical and Forensic Perspectives. Burlington, MA, USA: Jones & Bartlett. pp. 39–48, esp. 41, 43, 45ff. ISBN 978-1449617578. Retrieved 16 December 2015. Note: the active agent appears variously as cantharidin,:41 and "cantharadin":43,45ff or "canthariadin":238 (sic.).

- Schmitz, David G. (2013). "Overview of Cantharidin Poisoning (Blister Beetle Poisoning)". In Aiello, Susan E.; Moses, Michael A. (eds.). The Merck Veterinary Manual. Kenilworth, NJ, USA: Merck Sharp & Dohme. ISBN 978-0911910612.

- Evans, T.J. & Hooser, S.B. (2010). "Comparative Gastrointestinal Toxicity (Ch. 16)". In Hooser, Stephen & McQueen, Charlene (eds.). Comprehensive Toxicology (2nd ed.). London, ENG: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 195–206, esp. 202. ISBN 978-0080468846.

- Gwaltney-Brant, Sharon M.; Dunayer, Eric & Youssef, Hany (2012). "Terrestrial Zootoxins [Coleoptera: Meloidae (Blister Beetles)". In Gupta, Ramesh C. (ed.). Veterinary Toxicology: Basic and Clinical Principles (2nd ed.). London, ENG: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 975–978. ISBN 978-0123859266. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Karras, David J.; Farrell, S.E.; Harrigan, R.A.; Henretig, F.M.; Gealt, L. (1996). "Poisoning From "Spanish Fly" (Cantharidin)". Am. J. Emerg. Med. 14 (5): 478–483. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90158-8. PMID 8765116.

While most commonly available preparations of Spanish fly contain cantharidin in negligible amounts, if at all, the chemical is available illicitly in concentrations capable of causing severe toxicity.

- Wilson, C.R. (2010). "Methods for Analysis of Gastrointestinal Toxicants (Ch. 9)". In Hooser, Stephen; McQueen, Charlene (eds.). Comprehensive Toxicology (2nd ed.). London, ENG: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 145–152, esp. 150. ISBN 978-0080468846. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Davidson, Alan (1999). Jaine, Tom (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food. Vannithone, Soun (illustrator). Oxford, ENG: Oxford University Press. p. 671f. ISBN 978-0-19-211579-9. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- Green, Jonathon (12 October 2002). "Spoonfuls of paradise". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Theroux, Paul (1989). Riding the Iron Rooster. Ivy Books. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8041-0454-8.

- Ledermann, W. (1 October 2007). "Simón "Bolívar y las cantáridas". Revista Chilena de Infectología. 24 (5): 409–412. doi:10.4067/S0716-10182007000500012.

- Henriques, Peter R. (2000). The Death of George Washington: He Died as He Lived. Mount Vernon, VA: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. pp. 27–36. ISBN 978-0-931917-35-6.

- "Dec. 14, 1799: The excruciating final hours of President George Washington". PBS NewsHour. 14 December 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Spanish fly |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spanish fly. |