Dartington Hall

Dartington Hall in Dartington, near Totnes, Devon, England, is a country estate that is the headquarters of the Dartington Hall Trust, a charity specialising in the arts, social justice and sustainability. The estate dates from medieval times.

The Trust currently runs 16 charitable programmes, including Schumacher College and the Dartington International Summer School. In addition to developing and promoting arts and educational programmes, the Trust hosts other groups and acts as a venue for retreats.

The hall itself is a Grade I listed building. The gardens are Grade II* listed in the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[1]

Dartington Hall estate

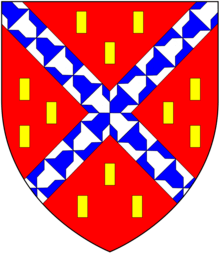

The Dartington Hall Trust is based on an historic 1,200 acres (4.9 km2) estate near Dartington in south Devon. The estate was held by the Martin family between the early 12th and mid 14th centuries but on the death of William Martin in 1326,[2] the feudal barony of Dartington escheated to the crown and in 1384 was granted by King Richard II to his half brother John Holland, 1st Duke of Exeter (c.1352-1400),[3] created in 1388 Earl of Huntingdon and in 1397 Duke of Exeter.

Historic buildings

The 1st Duke built the mediaeval hall between 1388 and his death in 1400 and the sculpted arms of Richard II survive on ribbed vault of the Porch.[4] The 1st Duke was beheaded by King Henry IV who had deposed Richard II, however Dartington continued as the seat of his son John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter (1395-1447) and grandson Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter (1430-1475) successively.[5] On the death of the 3rd Duke in 1475 without issue, supposedly drowned at sea on the orders of King Edward IV, Dartington again escheated to the crown. In 1559 it was acquired by Sir Arthur Champernowne, Vice-Admiral of the West under Elizabeth I, whose descendants in a direct male line lived in the Hall for 366 years until 1925.

Modern restoration

The hall was mostly derelict by the time it was bought in 1925 by the British-American millionaire couple Leonard Elmhirst (orig. from Yorkshire) and his wife Dorothy (née Whitney) from New York. They commissioned architect William Weir to renovate the buildings and restored the Great Hall's hammerbeam roof.[6] Inspired by a long association with Rabindranath Tagore's Shantiniketan, where Tagore was trying to introduce progressive education and rural reconstruction into a tribal community, they set out on a similar goal for the depressed agricultural economy in rural England.[7]

In 1928, Elmirst began collaborating with Alice Blinn, who worked for Delineator Home Institute and magazine of the same name, to create a home economics training center and design a system to modernize domestic activities of the village. Blinn prepared a report giving an overview of initiatives including education, apprenticeship programs, a laboratory, as well as a modern kitchen, cafeteria, laundry, and lavatories, with modern equipment and plumbing, based on what was available in a modern American home. Unable to persuade her to move from the United States to England and operate a training center, Elmhirst abandoned the plan of a demonstration kitchen. Blinn's recommended kitchen equipment was installed, but arranged in a typical English fashion, because the wife of the headmaster, did not like the efficient kitchen design.[8] In 1935, the Dartington Hall Trust, a registered charity, was set up in order to run the estate.

The estate comprises various schools, colleges and charitable and commercial organisations, including Schumacher College, the Arts at Dartington, the Dartington International Summer School of music, Research in Practice, Dartington School for Social Entrepreneurs and the Shops at Dartington (formerly the Cider Press Centre). In North Devon, the Beaford Centre, set up as an arts centre by the Trust in the 1960s to bring employment and culture to a rurally depressed area, continues to thrive. Until June 2010, prior to the college's contentious merger with University College Falmouth, the estate was also home to Dartington College of Arts.[9][10]

The Hall and mediaeval courtyard functions in part as a conference centre and wedding venue and provides bed and breakfast accommodation for people attending courses and for casual visitors. The Barn Cinema and the White Hart Bar and Restaurant are used by estate dwellers, residents from the surrounding countryside, and visitors alike.

High Cross House was built in 1932 as a home for the headmaster of Dartington Hall school, by art patrons Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst. It was designed by Swiss-American architect William Lescaze and is now regarded as an important modernist building. It is a Grade II* listed building.[11][12]

In May 2010, Sotheby's sold a group of 12 paintings by Rabindranath Tagore, which had been given by Tagore to his friend Leonard Elmhirst.[13] In Autumn 2011, The Trust proposed the sale of additional artworks by Ben Nicholson, Christopher Wood, Alfred Wallis and others, again at Sotheby's.[14] The sale generated some criticism from local people,[15] who voiced concerns about deaccessioning of the Trust's art assets. The Trust argued that the founders went to considerable lengths to make clear that art works and other assets could and should be used and sold at the discretion of the Trustees to support the activities of the Trust.[16]

Dartington International Summer School

Dartington International Summer School is a department of The Dartington Hall Trust. The Summer School is both a festival and a music school. Participants, both amateur musicians and advanced students, spend the daytime studying a variety of different musical courses, and the evenings attending (or performing in) concerts. In addition to instrumental and vocal masterclasses, there are courses at various levels on subjects such as composition, opera, chamber music, conducting and improvisation. Courses include choirs, orchestras, individual masterclasses, and non classical music such as Jazz, Salsa and Gamelan. Composition teachers have included Luciano Berio, Luigi Nono, Bruno Maderna, Harrison Birtwistle, Peter Maxwell Davies, Brian Ferneyhough, Witold Lutosławski and Elliott Carter.

Dartington Gardens

The gardens were created by Dorothy Elmhirst with the involvement of major landscape designers Beatrix Farrand and Percy Cane and feature a tiltyard (thought actually to be the remains of an Elizabethan water garden) and major sculptures, including examples by Henry Moore, Willi Soukop and Peter Randall-Page. There is an ancient yew tree (Taxus baccata) reputed to be nearly 2000 years old and rumour has it that Knights Templar are buried in the graveyard there, although there is no evidence to substantiate this.

Former activities

Dartington Hall School

Dartington Hall School, founded in 1926, offered a progressive coeducational boarding life. When it started there was a minimum of formal classroom activity and the children learned by involvement in estate activities. It was to have “no corporal punishment, indeed no punishment at all; no prefects; no uniforms; no Officers’ Training Corps; no segregation of the sexes; no compulsory games, compulsory religion or compulsory anything else, no more Latin, no more Greek; no competition; no jingoism.”[17]

With time more academic rigour was imposed, but it remained progressive and had mixed success educating the children, sometimes the more wayward ones, of the fee-paying parents. A noted alumnus was Lord Young, a founder of Which? and the Open University. Lucian Freud attended the school for two years and his brother Clement Freud was also a pupil there.[18] Other noted alumni include Eva Ibbotson, songwriter Kit Hain, Ivan Moffat, Jasper Fforde, Sheila Ernst, Lionel Grigson, Martin Bernal, Matthew Huxley, Max Fordham, Oliver Postgate,[19] Richard Leacock and the sculptor Sokari Douglas Camp.

W. B. Curry was headmaster of the school from 1931 to 1957, and wrote two books about it, The School, published by The Bodley Head in 1934, and Education for Sanity, published by Heinemann in 1947.[20]

The author Dennis Wheatley novelised the activities of some people based at the school in his 1947 book The Haunting of Toby Jugg. This was a supernatural thriller which sensationalised some real-life events before the war, setting them at a fictional school called "Weylands". Years later, it was revealed that these events had attracted the attention of MI5 in a declassified report called "The Case Against Dartington Hall".[21]

At its peak, the school had some 300 pupils. However, with the advent of state-based progressive education, the death of its founders, and the appointment of a new headmaster in whose time the school attracted considerable negative publicity - not least owing to his calling the police to the school to combat alcohol and drug abuse taking place, the death by drowning of a student, and his wife's modelling for pornographic photographs - the school suffered a dramatic drop in recruitment. The school was forced to close in 1987.[22] After the school's closure, a number of staff and students set up Sands School which still carries some of the principles that Dartington once had.

It has been suggested that the school 'Knotshead' in the novel A Private Place by Amanda Craig was based upon Dartington Hall school, as the events in the book are similar to those that occurred within the final years of Dartington Hall.[23]

Literary editor Miriam Gross wrote an account of her time at the school for the May 2011 edition of Standpoint magazine.[24]

Dartington College of Arts

Dartington College of Arts was a specialist arts institution based at the hall from 1961 to 2010, with an international reputation for excellence, focusing mainly on the performance arts. In 2008, it became part of University College Falmouth and subsequently relocated to Falmouth, Cornwall.

Gallery

Courtyard north entrance

Courtyard north entrance View of gardens and Hall

View of gardens and Hall Tower of the former St Mary's church

Tower of the former St Mary's church Zen garden

Zen garden North corner of Courtyard

North corner of Courtyard Gardens in winter

Gardens in winter

See also

- D. G. Champernowne, mathematician and economist, buried in the church yard

- Dart, a poem by Alice Oswald (Dartington Hall's gardener)

References

- Historic England. "Dartington Hall (1000453)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/arch-1132-1/dissemination/pdf/115/115_184_202.pdf

- Hoskins, W.G., A New Survey of England: Devon, London, 1959 (first published 1954), p.381

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1108353)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Pole, Sir William (d.1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, p.296

- Snell, Reginald (1986). William Weir and Dartington Hall. Dartington Hall Trust. ISBN 0-902386-10-7.

- Sen, Amartya (28 August 2001). "Tagore and His India". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- Jeremiah, David (1998). "Dartington, A Modern Adventure". In Smiles, Sam (ed.). Going Modern and Being British: Art, Architecture and Design in Devon C. 1910–1960. Exeter, England: Intellect Books. pp. 43–78. ISBN 978-1-871516-95-1.

- Steven Morris (28 December 2006). "Battle to save celebrated cradle of cutting edge art". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Anthea Lipsett (10 March 2008). "Last-ditch attempt to halt Dartington merger". Education Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Morris, Steven (4 April 2019). "Devon's 1930s High Cross House to reopen for culture festival". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Historic England. "High Cross Hill House (Grade II*) (1220922)". National Heritage List for England.

- Sotheby's to Sell Tagore Collection of The Dartington Hall Trust, artdaily.org. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- Sotheby's unveils a group of Modern British art from the Dartington Hall Trust Collection, artdaily.org. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- Row as Dartington Hall auctions off its treasures guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- On the sale of works of art from the collection Archived 2012-01-29 at the Wayback Machine dartington.org

- Young, Michael (1982), The Elmhirsts of Dartington, Routledge and Kegan Paul, p. 131.

- "Sir Clement Freud". Daily Telegraph. London. 16 April 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Hayward, Anthony (10 December 2008). "Oliver Postgate: Creator of 'Bagpuss', 'The Clangers' and 'Ivor the Engine' who turned children's television into an art form". The Independent. London. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Gribble, David (ed.), That’s All, Folks, Dartington Hall School Remembered; reminiscences and reflections of former pupils, West Aish Publishing, 1987. ISBN 0951273507

- "The 2014 Dennis Wheatley Convention". Archived from the original on 27 August 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015. Dartington Hall report at the end.

- https://www.theguardian.com/film/2005/jun/30/usa.world

- Waugh, Harriet (September 1991). "School for Scandal". The Spectator. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Gross, Miriam (May 2011). "An Experimental Education". Standpoint. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

Further reading

- Anonymous, Dartington, Webb & Bower, 1982.

- Bonham-Carter, Victor (1970) [1958]. Dartington Hall: the Formative Years 1925-1957. Dulverton (Somerset): Exmoor Press. ISBN 0-9500133-9-0.

- Wheatley, Dennis. The Haunting of Toby Jugg (1947). Critical novel, based on life at the school.

- Punch, Maurice (1977). Progressive Retreat: a Sociological Study of Dartington Hall School, 1926-1957, and Some of its Former Pupils. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-21182-4.

- Young, Michael (1982). The Elmhirsts of Dartington: the Creation of an Utopian Community. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-07-100905-1.

- MacManus, Steve (2017). Elmsworld. My Life At Dartington Hall School 1963-1971, eBook Publication, ISBN 9781973315742.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dartington Hall. |