Dandy

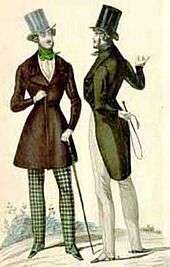

A dandy, historically, is a man who places particular importance upon physical appearance, refined language, and leisurely hobbies, pursued with the appearance of nonchalance in a cult of self.[1][2][3] A dandy could be a self-made man who strove to imitate an aristocratic lifestyle despite coming from a middle-class background, especially in late 18th- and early 19th-century Britain.

Previous manifestations of the petit-maître (French for "small master") and the Muscadin have been noted by John C. Prevost,[4] but the modern practice of dandyism first appeared in the revolutionary 1790s, both in London and in Paris. The dandy cultivated cynical reserve, yet to such extremes that novelist George Meredith, himself no dandy, once defined cynicism as "intellectual dandyism". Some took a more benign view; Thomas Carlyle wrote in Sartor Resartus that a dandy was no more than "a clothes-wearing man". Honoré de Balzac introduced the perfectly worldly and unmoved Henri de Marsay in La fille aux yeux d'or (1835), a part of La Comédie Humaine, who fulfils at first the model of a perfect dandy, until an obsessive love-pursuit unravels him in passionate and murderous jealousy.

Charles Baudelaire defined the dandy, in the later "metaphysical" phase of dandyism,[5] as one who elevates æsthetics to a living religion,[6] that the dandy's mere existence reproaches the responsible citizen of the middle class: "Dandyism in certain respects comes close to spirituality and to stoicism" and "These beings have no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons, of satisfying their passions, of feeling and thinking .... Dandyism is a form of Romanticism. Contrary to what many thoughtless people seem to believe, dandyism is not even an excessive delight in clothes and material elegance. For the perfect dandy, these things are no more than the symbol of the aristocratic superiority of mind."

The linkage of clothing with political protest had become a particularly English characteristic during the 18th century.[7] Given these connotations, dandyism can be seen as a political protest against the levelling effect of egalitarian principles, often including nostalgic adherence to feudal or pre-industrial values, such as the ideals of "the perfect gentleman" or "the autonomous aristocrat". Paradoxically, the dandy required an audience, as Susann Schmid observed in examining the "successfully marketed lives" of Oscar Wilde and Lord Byron, who exemplify the dandy's roles in the public sphere, both as writers and as personae providing sources of gossip and scandal.[8] Nigel Rodgers in The Dandy: Peacock or Enigma? questions Wilde's status as a genuine dandy, seeing him as someone who only assumed a dandified stance in passing, not a man dedicated to the exacting ideals of dandyism.

Etymology

The origin of the word is uncertain. Eccentricity, defined as taking characteristics such as dress and appearance to extremes, began to be applied generally to human behavior in the 1770s;[9] similarly, the word dandy first appears in the late 18th century: In the years immediately preceding the American Revolution, the first verse and chorus of "Yankee Doodle" derided the alleged poverty and rough manners of American-citizen colonists, suggesting that whereas a fine horse and gold-braided clothing ("mac[c]aroni") were required to set a dandy apart from those around him, the average American citizen-colonist's means were so meager that ownership of a mere pony and a few feathers for personal ornamentation would qualify one of them as a "dandy" by comparison to and/or in the minds of his even less sophisticated Eurasian compatriots.[10] A slightly later Scottish border ballad, circa 1780,[11] also features the word, but probably without all the contextual aspects of its more recent meaning. The original, full form of 'dandy' may have been jack-a-dandy.[12] It was a vogue word during the Napoleonic Wars. In that contemporary slang, a "dandy" was differentiated from a "fop" in that the dandy's dress was more refined and sober than the fop's.

In the twenty-first century, the word dandy is a jocular, often sarcastic adjective meaning "fine" or "great"; when used in the form of a noun, it refers to a well-groomed and well-dressed man, but often to one who is also self-absorbed.[13]

Beau Brummell and early British dandyism

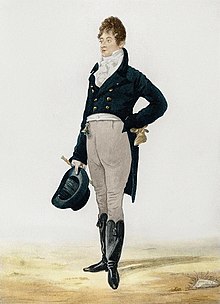

The model dandy in British society was George Bryan "Beau" Brummell (1778–1840), in his early days, an undergraduate student at Oriel College, Oxford and later, an associate of the Prince Regent. Brummell was not from an aristocratic background; indeed, his greatness was "based on nothing at all," as J.A. Barbey d'Aurevilly observed in 1845.[14] Never unpowdered or unperfumed, immaculately bathed and shaved, and dressed in a plain dark blue coat,[15] he was always perfectly brushed, perfectly fitted, showing much perfectly starched linen, all freshly laundered, and composed with an elaborately knotted cravat. From the mid-1790s, Beau Brummell was the early incarnation of "the celebrity", a man chiefly famous for being famous.[16]

By the time Pitt taxed hair powder in 1795 to help pay for the war against France and to discourage the use of flour (which had recently increased in both rarity and price, owing to bad harvests) in such a frivolous product, Brummell had already abandoned wearing a wig, and had his hair cut in the Roman fashion, "à la Brutus". Moreover, he led the transition from breeches to snugly tailored dark "pantaloons," which directly led to contemporary trousers, the sartorial mainstay of men's clothes in the Western world for the past two centuries. In 1799, upon coming of age, Beau Brummell inherited from his father a fortune of thirty thousand pounds, which he spent mostly on costume, gambling, and high living. In 1816 he suffered bankruptcy, the dandy's stereotyped fate; he fled his creditors to France, quietly dying in 1840, in a lunatic asylum in Caen, aged 61.[17]

Men of more notable accomplishments than Beau Brummell also adopted the dandiacal pose: Lord Byron occasionally dressed the part, helping reintroduce the frilled, lace-cuffed and lace-collared "poet shirt". In that spirit, he had his portrait painted in Albanian costume.[18]

Another prominent dandy of the period was Alfred Guillaume Gabriel d'Orsay, the Count d'Orsay, who had been friends with Byron and who moved in the highest social circles of London.

In 1836 Thomas Carlyle wrote:

A Dandy is a clothes-wearing Man, a Man whose trade, office and existence consists in the wearing of Clothes. Every faculty of his soul, spirit, purse, and person is heroically consecrated to this one object, the wearing of Clothes wisely and well: so that the others dress to live, he lives to dress ... And now, for all this perennial Martyrdom, and Poesy, and even Prophecy, what is it that the Dandy asks in return? Solely, we may say, that you would recognise his existence; would admit him to be a living object; or even failing this, a visual object, or thing that will reflect rays of light...[19]

By the mid-19th century, the English dandy, within the muted palette of male fashion, exhibited minute refinements—"The quality of the fine woollen cloth, the slope of a pocket flap or coat revers, exactly the right colour for the gloves, the correct amount of shine on boots and shoes, and so on. It was an image of a well-dressed man who, while taking infinite pains about his appearance, affected indifference to it. This refined dandyism continued to be regarded as an essential strand of male Englishness."[20]

Dandyism in France

The beginnings of dandyism in France were bound to the politics of the French revolution; the initial stage of dandyism, the gilded youth, was a political statement of dressing in an aristocratic style in order to distinguish its members from the sans-culottes.

During his heyday, Beau Brummell's dictat on both fashion and etiquette reigned supreme. His habits of dress and fashion were much imitated, especially in France, where, in a curious development, they became the rage, especially in bohemian quarters. There, dandies sometimes were celebrated in revolutionary terms: self-created men of consciously designed personality, radically breaking with past traditions. With elaborate dress and idle, decadent styles of life, French bohemian dandies sought to convey contempt for and superiority to bourgeois society. In the latter 19th century, this fancy-dress bohemianism was a major influence on the Symbolist movement in French literature.[22]

Baudelaire was deeply interested in dandyism, and memorably wrote that a dandy aspirant must have "no profession other than elegance... no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons... The dandy must aspire to be sublime without interruption; he must live and sleep before a mirror." Other French intellectuals also were interested in the dandies strolling the streets and boulevards of Paris. Jules Amédée Barbey d'Aurevilly wrote On Dandyism and George Brummell, an essay devoted, in great measure, to examining the career of Beau Brummell.[23]

Later dandyism

The literary dandy is a familiar figure in the writings, and sometimes the self-presentation, of Oscar Wilde, H.H. Munro (Clovis and Reginald), P.G. Wodehouse (Bertie Wooster) and Ronald Firbank, writers linked by their subversive air.

The poets Algernon Charles Swinburne and Oscar Wilde, Walter Pater, the American artist James McNeill Whistler, the Spanish artist Salvador Dalí, Joris-Karl Huysmans, and Max Beerbohm were dandies of the Belle Époque, as was Robert de Montesquiou — Marcel Proust's inspiration for the Baron de Charlus. In Italy, Gabriele d'Annunzio and Carlo Bugatti exemplified the artistic bohemian dandyism of the fin de siecle. Wilde wrote that, "One should either be a work of Art, or wear a work of Art."

At the end of the 19th century, American dandies were called dudes. Evander Berry Wall was nicknamed the "King of the Dudes".

George Walden, in the essay Who's a Dandy?, identifies Noël Coward, Andy Warhol, and Quentin Crisp as modern dandies.[23] The character Psmith in the novels of P. G. Wodehouse is considered a dandy, both physically and intellectually. Agatha Christie's Poirot is said to be a dandy.

The artist Sebastian Horsley described himself as a "dandy in the underworld" in his eponymous autobiography.[24]

In Japan, dandyism has become a fashion subculture[25] with historical roots dating back to the Edo period.[26]

In Spain during the early 19th century a curious phenomenon developed linked to the idea of dandyism. While in England and France individuals from the middle classes adopted aristocratic manners, the Spanish aristocracy adopted the fashions of the lower classes, called majos. They were characterized by their elaborate outfits and sense of style as opposed to the modern Frenchified "afrancesados", as for their cheeky arrogant attitude. Some famous dandies in later times were amongst other the Duke of Osuna, Mariano Tellez-Girón, artist Salvador Dalí and poet Luís Cernuda.

Later thought

Albert Camus said in L'Homme révolté (1951) that:

The dandy creates his own unity by aesthetic means. But it is an aesthetic of negation. "To live and die before a mirror": that according to Baudelaire, was the dandy's slogan. It is indeed a coherent slogan. The dandy is, by occupation, always in opposition. He can only exist by defiance... The dandy, therefore, is always compelled to astonish. Singularity is his vocation, excess his way to perfection. Perpetually incomplete, always on the fringe of things, he compels others to create him, while denying their values. He plays at life because he is unable to live it.[27]

Jean Baudrillard said that dandyism is "an aesthetic form of nihilism".[28]

Quaintrelle

The female counterpart is a quaintrelle, a woman who emphasizes a life of passion expressed through personal style, leisurely pastimes, charm, and cultivation of life's pleasures.

In the 12th century, cointerrels (male) and cointrelles (female) emerged, based upon coint,[29] a word applied to things skillfully made, later indicating a person of beautiful dress and refined speech.[30] By the 18th century, coint became quaint,[31] indicating elegant speech and beauty. Middle English dictionaries note quaintrelle as a beautifully dressed woman (or overly dressed), but do not include the favorable personality elements of grace and charm. The notion of a quaintrelle sharing the major philosophical components of refinement with dandies is a modern development that returns quaintrelles to their historic roots.

Female dandies did overlap with male dandies for a brief period during the early 19th century when dandy had a derisive definition of "fop" or "over-the-top fellow"; the female equivalents were dandyess or dandizette.[30] Charles Dickens, in All the Year Around (1869) comments, "The dandies and dandizettes of 1819–20 must have been a strange race. "Dandizette" was a term applied to the feminine devotees to dress, and their absurdities were fully equal to those of the dandies."[32] In 1819, Charms of Dandyism in three volumes, was published by Olivia Moreland, Chief of the Female Dandies; most likely one of many pseudonyms used by Thomas Ashe. Olivia Moreland may have existed, as Ashe did write several novels about living persons. Throughout the novel, dandyism is associated with "living in style". Later, as the word dandy evolved to denote refinement, it became applied solely to men. Popular Culture and Performance in the Victorian City (2003) notes this evolution in the latter 19th century: "...or dandizette, although the term was increasingly reserved for men."

In Popular Culture

Jason King

The series featured the further adventures of the title character played by Peter Wyngarde who had first appeared in Department S (1969). In that series he was a dilettante, dandy, and author of a series of adventure novels, working as part of a team of investigators. In Jason King he had left that service to concentrate on writing the adventures of Mark Caine, who closely resembled Jason King in looks, manner, style, and personality. None of the other regular characters from Department S appeared in this series, although Department S itself is occasionally referred to in dialogue.

See also

- Dandy and Dedicated Follower of Fashion, songs by The Kinks that parody modern (1960s) dandyism.

- Adonis

- Bishōnen

- Dude

- Effeminacy

- Flâneur

- Fop

- Gentleman

- Hipster (contemporary subculture)

- Incroyables and Merveilleuses

- La Sape

- Macaroni

- Metrosexual

- Narcissus (mythology)

- Preppy

- Risqué

- Swenkas

References

- "One who studies ostentatiously to dress fashionably and elegantly; a fop, an exquisite." (OED).

- Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1989.

dude, n. U.S.A name given in ridicule to a man affecting an exaggerated fastidiousness in dress, speech, and deportment, and very particular about what is æsthetically 'good form'; hence, extended to an exquisite, a dandy, 'a swell'.

- Cult de soi-même, Charles Baudelaire, "Le Dandy", noted in Susann Schmid, "Byron and Wilde: The Dandy in the Public Sphere" in Julie Hibbard et al. , eds. The Importance of Reinventing Oscar: versions of Wilde during the last 100 years 2002

- Le Dandysme en France (1817–1839) (Geneva and Paris) 1957.

- See Prevost 1957.

- Baudelaire, in his essay about painter Constantin Guys, "The Painter of Modern Life".

- Aileen Ribeiro, "On Englishness in dress" in The Englishness of English Dress, Christopher Breward, Becky Conekin and Caroline Cox, ed., 2002.

- Schmid 2002.

- Ribeiro 2002:20, under the subheading "Eccentricity, Extremes, and Affectation".

- "Yankee Doodle"; Maccaroni.

- Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1989.

dandy 1.a. One who studies above everything to dress elegantly and fashionably; a beau, fop, 'exquisite'. c1780 Sc. Song (see N. & Q. 8th Ser. IV. 81), I've heard my granny crack O' sixty twa years back When there were sic a stock of Dandies O; Oh they gaed to Kirk and Fair, Wi' their ribbons round their hair, And their stumpie drugget coats, quite the Dandy O.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911

- See, for example, the Dandyism blog by Christian Chensvold, continually since 2004, but with a published record on the subject since the mid-1990s. http://www.dandyism.net

- Barbey d'Aurevilly, "Du dandisme et de George Brummell," (published 1845, collected in Oeuvres complètes 1925:87–92).

- "In Regency England, Brummel's fashionable simplicity constituted in fact a criticism of the exuberant French fashions of the eighteenth century" (Schmid 2002:83),

- Kelly, Ian (2006). Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style. New York: Free Press. ISBN 9780743270892.

- Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 6018–6019). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- "Portrait of Lord Byron in Albanian Dress, 1813". The British Library. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Thomas Carlyle, "The Dandiacal Body", in Sartor Resartus

- Ribeira 2002:21.

- William R. Denslow (September 2004). 10,000 Famous Freemasons from K to Z. Kessinger Publishing. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-4179-7579-2.

- Roman Meinhold, trans. John Irons. "The Ideal-Typical Incarnation of Fashion: The Dandy as...", in Fashion Myths: A Cultural Critique. Bielefeld, Germany: transcript, 2014. 111-25. books.google.com/books?id=1XWiBQAAQBAJ ISBN 9783839424377

- George Walden, Who's a Dandy? – Dandyism and Beau Brummell, Gibson Square, London, 2002. ISBN 1903933188. Reviewed by Frances Wilson in Uncommon People, The Guardian, 12 October 2006.

- Beautiful and damned, New Statesman, 16 October 2006

- Pask, Bruce (16 January 2009). "The New Japanese Dandyism". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

Burton, Tara Isabella (14 December 2016). "Identity and the Rise of Dandyism, From Congo to Kyoto". The Village Voice. New York City. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

Toby Slade (1 November 2009). Japanese Fashion: A Cultural History. Berg. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-1-84788-748-1. - Kikuchi, Daisuke (2 June 2015). "The World of Edo Dandyism: From Swords to Inro". The Japan Times. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

Masafumi Monden (20 November 2014). Japanese Fashion Cultures: Dress and Gender in Contemporary Japan. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-4725-8673-5. - Camus, Albert (2012). "II Metaphysical Rebellion". The Rebel: An Essay on Man in Revolt. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 51. ISBN 9780307827838. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- "Jean Baudrillard – Simulacra and Simulations – XVIII. On Nihilism". Egs.edu. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Old English Dictionary

- Brooks, Ann (15 July 2014). Popular Culture: Global Intercultural Perspectives. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 9781137426727.

- Dictionary of Early English

- All the Year Round: A Weekly Journal. Chapman & Hall. 1869.

Further reading

- Barbey d'Aurevilly, Jules. Of Dandyism and of George Brummell. Translated by Douglas Ainslie. New York: PAJ Publications, 1988.

- Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten. 'Rulefollowing in Dandyism: Style as an Overcoming of Rule and Structure' in The Modern Language Review 90, April 1995, pp. 285–295.

- Carassus, Émile. Le Mythe du Dandy 1971.

- Carlyle, Thomas. Sartor Resartus. In A Carlyle Reader: Selections from the Writings of Thomas Carlyle. Edited by G.B. Tennyson. London: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Jesse, Captain William. The Life of Beau Brummell. London: The Navarre Society Limited, 1927.

- Lytton, Edward Bulwer, Lord Lytton. Pelham or the Adventures of a Gentleman. Edited by Jerome McGann. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1972.

- Moers, Ellen. The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm. London: Secker and Warburg, 1960.

- Murray, Venetia. An Elegant Madness: High Society in Regency England. New York: Viking, 1998.

- Nicolay, Claire. Origins and Reception of Regency Dandyism: Brummell to Baudelaire. PhD diss., Loyola U of Chicago, 1998.

- Prevost, John C., Le Dandysme en France (1817–1839) (Geneva and Paris) 1957.

- Nigel Rodgers The Dandy: Peacock or Enigma? (London) 2012

- Stanton, Domna. The Aristocrat as Art 1980.

- Wharton, Grace and Philip. Wits and Beaux of Society. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1861.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dandy |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dandies. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). 1911.

- La Loge d'Apollon

- "Bohemianism and Counter-Culture": The Dandy

- Il Dandy (in Italian)

- Dandyism.net

- "The Dandy"

- Walter Thornbury, Dandysme.eu "London Parks: IV. Hyde Park", Belgravia: A London Magazine 1868