Ninhursag

Ninḫursaĝ,[lower-alpha 1] also known as Damgalnuna or Ninmah, was the ancient Sumerian mother goddess of the mountains, and one of the seven great deities of Sumer. She is principally a fertility goddess. Temple hymn sources identify her as the "true and great lady of heaven" (possibly in relation to her standing on the mountain) and kings of Sumer were "nourished by Ninhursag's milk". Sometimes her hair is depicted in an omega shape and at times she wears a horned head-dress and tiered skirt, often with bow cases at her shoulders. Frequently she carries a mace or baton surmounted by an omega motif or a derivation, sometimes accompanied by a lion cub on a leash. She is the tutelary deity to several Sumerian leaders.

| Ninhursag | |

|---|---|

Mother goddess, goddess of fertility, mountains, and rulers | |

Akkadian cylinder seal impression depicting a vegetation goddess, possibly Ninhursag, sitting on a throne surrounded by worshippers (circa 2350-2150 BC) | |

| Symbol | Omega-like symbol |

| Personal information | |

| Consort | Enki |

| Children | Ninurta, Ninsar, Abu, Nintulla (Nintul), Ninsutu, Ninkasi, Nanshe (Nazi), Azimua, Ninti, Enshag (Enshagag) |

Names

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

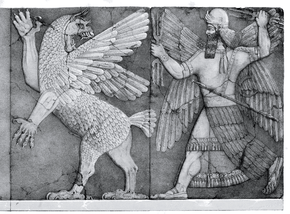

Chaos Monster and Sun God |

|

Seven gods who decree

|

|

Other major deities |

|

Demigods and heroes

|

| Related topics |

Nin-hursag means "lady of the sacred mountain" (from Sumerian NIN "lady" and ḪAR.SAG "sacred mountain, foothill",[9] possibly a reference to the site of her temple, the E-Kur (House of mountain deeps) at Eridu. She had many names including Ninmah ("Great Queen");[9] Nintu ("Lady of Birth");[9] Mamma or Mami (mother);[9] Aruru,[9] Belet-Ili (lady of the gods, Akkadian)[9]

According to legend, her name was changed from Ninmah to Ninhursag by her son Ninurta in order to commemorate his creation of the mountains. As Ninmenna, according to a Babylonian investiture ritual, she placed the golden crown on the king in the Eanna temple.[10]

Some of the names above were once associated with independent goddesses (such as Ninmah and Ninmenna), who later became identified and merged with Ninhursag, and myths exist in which the name Ninhursag is not mentioned.

Possibly included among the original mother goddesses was Damgalnuna (great wife of the prince) or Damkina (true wife), the consort of the god Enki.[11] The mother goddess had many epithets including shassuru or 'womb goddess', tabsut ili 'midwife of the gods', 'mother of all children' and 'mother of the gods'. In this role she is identified with Ki in the Enuma Elish. She had shrines in both Eridu and Kish.

Mythology

In the legend of Enki and Ninhursag, Ninhursag bore a daughter to Enki called Ninsar ("Lady Greenery"). Through Enki, Ninsar bore a daughter Ninkurra ("Lady of the Pasture"). Ninkurra, in turn, bore Enki a daughter named Uttu. Enki then pursued Uttu, who was upset because he didn't care for her. Uttu, on her ancestress Ninhursag's advice buried Enki's seed in the earth, whereupon eight plants (the very first) sprung up. Enki, seeing the plants, ate them, and became ill in eight organs of his body. Ninhursag cured him, taking the plants into her body and giving birth to eight deities: Abu, Nintulla (Nintul), Ninsutu, Ninkasi, Nanshe, Azimua, Ninti, and Enshag (Enshagag).

In the text 'Creator of the Hoe', she completed the birth of mankind after the heads had been uncovered by Enki's hoe.

In creation texts, Ninmah (another name for Ninhursag) acts as a midwife whilst the mother goddess Nammu makes different kinds of human individuals from lumps of clay at a feast given by Enki to celebrate the creation of humankind.

Worship

Her symbol, resembling the Greek letter omega Ω, has been depicted in art from approximately 3000 BC, although more generally from the early second millennium BC. It appears on some boundary stones—on the upper tier, indicating her importance. The omega symbol is associated with the Egyptian cow goddess Hathor, and may represent a stylized womb.[12] The symbol appears on very early imagery from Ancient Egypt. Hathor is at times depicted on a mountain, so it may be that the two goddesses are connected.

Her temple, the Esagila (from Sumerian E (temple) + SAG (head) + ILA (lofty)) was located on the KUR of Eridu, although she also had a temple at Kish.

See also

References

- [King, L. W., Hall, H. R., History of Egypt Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria in the Light of Recent Discovery, p. 117, The Echo Library, 2008.]

- Jastrow, Morris (February 16, 1898). "The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria". Ginn – via Google Books.

- Van Buren, E. Douglas (February 16, 1930). "Clay Figurines of Babylonia and Assyria". AMS Press – via Google Books.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (February 16, 1979). "Ancient Cities of the Indus". Carolina Academic Press – via Google Books.

- Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (February 16, 1932). "Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland". Cambridge University Press for the Royal Asiatic Society – via Google Books.

- Clay, Albert T. (July 16, 1997). "The Origin of Biblical Traditions: Hebrew Legends in Babylonia and Israel". Book Tree – via Google Books.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (March 1, 2003). "Babylonian Life and History". Kessinger Publishing – via Google Books.

- "Edwardes, Marian & Spence, Lewis., Dictionary of Non-Classical Mythology, p.126, Kessinger Publishing, 2003".

- Dalley, Stephanie (1998). Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-19-283589-5.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1976). Eanna%20temple.&pg=PA109#v=onepage&q=Ninmenna,%20placed%20the%20golden%20crown%20on%20the%20king%20in%20the%20Eanna%20temple.&f=false The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. Yale University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780300022919. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Jeremy A. Black, Anthony Green, Tessa Rickards, Gods, demons, and symbols of ancient Mesopotamia: an illustrated dictionary (1992), p. 56f. & 75

- "Of Omegas and Rhombs by Johanna Stuckey". www.matrifocus.com.

- Michael Jordan, Encyclopedia of Gods, Kyle Cathie Limited, 2002

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg)