History of Arda

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the history of Arda[lower-alpha 1] began when the Ainur entered Arda, following the creation events in the Ainulindalë and long ages of labour throughout Eä, the fictional universe. Time from that point was measured using Valian Years, though the subsequent history of Arda was divided into three time periods using different years, known as the Years of the Lamps, the Years of the Trees and the Years of the Sun. A separate, overlapping chronology divides the history into 'Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar'. The first such Age began with the Awakening of the Elves during the Years of the Trees and continued for the first six centuries of the Years of the Sun. All the subsequent Ages took place during the Years of the Sun. Most Middle-earth stories take place in the first three Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar.

Arda is, as critics have noted, "our own green and solid Earth at some quite remote epoch in the past."[1] As such, it has not only an immediate story but a history, and the whole thing is an "imagined prehistory"[3] of the Earth as it is now.

Music of the Ainur

The supreme deity of Tolkien's universe is Eru Ilúvatar. Ilúvatar created spirits named the Ainur from his thoughts, and some were considered brothers or sisters. Ilúvatar made divine music with them. Melkor, then the most powerful of the Ainur, broke the harmony of the music, until Ilúvatar began first a second theme, and then a third theme, which the Ainur could not comprehend since they were not the source of it. The essence of their song symbolized the history of the whole universe and the Children of Ilúvatar that were to dwell in it—Men and Elves.[T 1]

Then Ilúvatar created Eä, which means "to be," the universe itself, and formed within it Arda, the Earth, "globed within the void": the world together with the three airs is set apart from Avakúma, the "void" without. The first 15 of the Ainur that descended to Arda, and the most powerful ones, were called Valar, and the lesser Ainur were called Maiar.[T 1]

Valian years

The Valian years measure the passage of time after the arrival of the Ainur in Arda. This definition of a year, named for the Valar, continued to be used during later periods. The Valian years were measured in Aman after the first sunrise, but Tolkien provided no dates for events in Aman after that point. The account in Valian years is generally not used when describing the events of Beleriand and Middle-earth. In the 1930s and 40s Tolkien used a figure which fluctuated slightly around ten before settling on 9.582 solar years in each Valian year. However, in the 1950s Tolkien decided to use a much greater value of 144 solar years per Valian year.

Spring of Arda

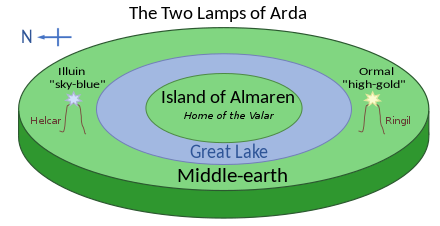

When the Valar entered Arda, it was still lifeless and had no distinct geographical features. The initial shape of Arda, chosen by the Valar, was much more symmetrical, including the central continent of Middle-earth. Middle-earth was also originally much larger, and was lit by the misty light that veiled the barren ground. The Valar concentrated this light in two large lamps, called Illuin and Ormal. The Vala Aulë forged two great pillar-like mountains, Helcar in the north and Ringil in the south. Illuin was set upon Helcar and Ormal upon Ringil. In the middle, where the light of the lamps mingled, the Valar dwelt at the island of Almaren upon the Great Lake.[T 2]

This period, known as the Spring of Arda, was a time when the Valar had ordered the World as they wished and rested upon Almaren, and Melkor lurked beyond the Walls of Night. During this time animals first appeared, and forests started to grow.[T 2]

The Spring of Arda was interrupted when Melkor returned to Arda, and ended completely when he assaulted and destroyed the Lamps of the Valar. Arda was again darkened, and the fall of the great Lamps spoiled the symmetry of Arda's surface. New continents were created: Aman in the West, Middle-earth proper in the middle, the uninhabited lands (later called the Land of the Sun) in the East. At the site of the northern lamp was later the inland Sea of Helcar, of which Cuiviénen was a bay. At the site of the southern lamp was later the Sea of Ringil. After the destruction of the Two Lamps the Years of the Lamps ended and the Years of the Trees began.[T 2]

Years of the Trees

Shortly after the destruction of the Two Lamps and the kingdom of Almaren, the Valar abandoned Middle-earth, moving to the continent of Aman. There they built their Second Kingdom, Valinor. Yavanna made the Two Trees, named Telperion (the silver tree) and Laurelin (the golden tree) in the land of Valinor. The Trees illuminated Valinor, leaving Middle-earth in darkness lit only by stars. The Years of the Trees were contemporary with Middle-earth's Sleep of Yavanna (recalled by Treebeard as the Great Darkness).[T 2]

The Years of the Trees were divided into two epochs. The first ten Ages, the Years of Bliss, saw peace and prosperity in Valinor. The Eagles, the Ents and the Dwarves were conceived by Manwë, Yavanna, and Aulë respectively, but placed into slumber until after the awakening of the Elves. The next ten Ages, called the Noontide of the Blessed Realm, saw Varda rekindling the stars above Middle-earth. This was the first time after the Spring of Arda that Middle-earth was illuminated. The first Elves awoke in Cuiviénen in the middle of Middle-earth, marking the start of the First Age of the Children of Ilúvatar, and were soon approached by the Enemy Melkor who hoped to enslave them. Learning of this, the Valar and the Maiar came into Middle-earth and, in the War of the Powers (also called the Battle of the Powers), defeated Melkor and brought him captive to Valinor. This began the period of the Peace of Arda.[T 3]

After the War of the Powers, Oromë of the Valar summoned the Elves to Aman. Many of the Elves went with Oromë on the Great Journey westwards towards Aman. Along the journey several groups of Elves tarried, notably the Nandor and the Sindar. The three clans that arrived at Aman were the Vanyar, Noldor and the Teleri. They made their home in Eldamar.[T 4] After Melkor appeared to repent and was released after his servitude of three Ages, he stirred up rivalry between the Noldorin King Finwë's two sons Fëanor and Fingolfin. With the help of Ungoliant, he killed Finwë and stole the Silmarils, three gems crafted by Fëanor that contained light of the Two Trees, from his vault, and destroyed the Trees of the Valar. The world was again dark, save for the faint starlight.[T 5][T 6]

Bitter at the Valar's inactivity, Fëanor and his house left to pursue Melkor, cursing him with the name "Morgoth".[T 7] While his brother Finarfin chose to stay in Valinor, a larger host led by Fingolfin followed Fëanor. They reached Alqualondë, the port-city of the Teleri, who forbade them from taking their ships for the journey to Middle-earth. The first Kinslaying thus ensued, and a curse was put on the house of the Noldor forever. Fëanor's host sailed on the boats, leaving Fingolfin's host behind—who crossed over to Middle-earth on the Helcaraxë or Grinding Ice in the far north, losing many. The War of the Great Jewels followed, and lasted until the end of the First Age. Meanwhile, the Valar took the last living fruit of Laurelin and the last living flower of Telperion and used them to create the Moon and Sun, which remained a part of Arda, but were separate from Ambar (the world). The first rising of the sun over Ambar heralded the end of the Years of the Trees, and the start of the Years of the Sun, which last to the present day.[T 8]

Years of the Sun

The Years of the Sun were the last of the three great time-periods of Arda. They began with the first sunrise in conjunction with the return of the Noldor to Middle-earth, and last until the present day.[T 9] The Years of the Sun began towards the end of the First Age of the Children of Ilúvatar and continued through the Second, Third, and part of the Fourth in Tolkien's stories. Tolkien estimated that modern times would correspond to the sixth or seventh age.[T 10]

| Age | Duration years | Began years ago | End event |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years of the Lamps | End of the Spring of Arda: Melkor destroys the Lamps Arda's symmetry broken Aman and Middle-earth created The Valar move to Aman | ||

| Years of the Trees | Melkor steals the Silmarils Ungoliant kills the Two Trees of Valinor | ||

| (Years of the Sun) First Age "Elder Days" | 1,033 | 13,495 | War of Wrath: Morgoth's defeat in Beleriand Thangorodrim broken Most of Beleriand drowned |

| Second Age | 3,441 | 12,462 | Akallabêth: Sauron's first downfall World made round Númenor drowned Valinor removed from Arda |

| Third Age | 3,021 | 9,021 | War of the Ring: Final defeat of Sauron Destruction of the One Ring Elves depart from Middle-earth |

| Fourth Age Fifth Age Sixth Age? Seventh Age?[T 10] | 6,000 | 6,000[T 10] | Middle-earth breaks up Continents rearrange To present day, modern life |

Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar

The First Age of the Children of Ilúvatar, or Eruhíni, began during the Years of the Trees when the Elves awoke in Cuiviénen in the middle-east of Middle-earth. This marked the start of the years when the Children of Ilúvatar were active in Middle-earth.[T 11] Later in the First Age the second kindred, humans, also awoke.

In some texts Tolkien referred to the 'First Age of Middle-earth' or the 'First Age of the World' rather than the 'First Age of the Children of Ilúvatar'. These variations had earlier starting points, extending the First Age back to the creation of Arda, but consistently ended with Morgoth's defeat in Beleriand. Each Age ended following a major event in the history of the Children of Ilúvatar.

First Age

The First Age of the Children of Ilúvatar, also referred to as the Elder Days in The Lord of the Rings, began during the Years of the Trees when the Elves awoke at Cuiviénen, and hence the events mentioned above under Years of the Trees overlap with the beginning of the First Age.[T 11]

Having crossed into Middle-earth, Fëanor was soon lost in an attack on Morgoth's Balrogs—but his sons survived and founded realms, as did the followers of his half-brother Fingolfin, who reached Beleriand after Fëanor's death. The Noldor for a time maintained the Siege of Angband, Morgoth's stronghold, resulting in the Long Peace. This Peace lasted hundreds of years, during which time Men arrived over the Blue Mountains.[T 12] Morgoth broke the siege in the Dagor Bragollach, or the Battle of Sudden Flame.[T 13] The Eldar, Edain and the Dwarves were defeated in the Nírnaeth Arnoediad or Battle of Unnumbered Tears,[T 14] and one by one, the kingdoms fell, even the hidden ones of Doriath[T 15] and Gondolin.[T 16]

At the end of the age, all that remained of free Elves and Men in Beleriand was a settlement at the mouth of the River Sirion and another on the Isle of Balar. Eärendil possessed the Silmaril which his wife Elwing's grandparents, Beren and Lúthien, had taken from Morgoth. But Fëanor's sons still maintained that all the Silmarils belonged to them, and so there were two more Kinslayings.[T 15][T 18] Eärendil and Elwing crossed the Great Sea to beg the Valar for aid against Morgoth. They responded, sending forth a great host. In the War of Wrath, Melkor was utterly defeated. He was expelled into the Void and most of his works were destroyed. This came at a terrible cost, however, as most of Beleriand itself was sunk.[T 18]

In a letter, Tolkien wrote that "This legendarium [of the First Age, The Silmarillion] ends with a vision of the end of the world, its breaking and remaking, and the recovery of the Silmarilli and the 'light before the Sun' – after a final battle [The War of Wrath] which owes, I suppose, more to the Norse vision of Ragnarök than to anything else, though it is not much like it."[T 17] The Tolkien commentator David Day supports Tolkien's comparison, noting that both battles begin with a horn-blast (the Horn of the Maia Eönwë, the Gjallarhorn of the god Heimdall), and that in both, there is a giant antagonist (Gothmog the Balrog, Surt the fire giant) armed with a flaming sword.[4][5]

Second Age

The Second Age is characterized by the establishment and flourishing of Númenor, the rise of Sauron in Middle-earth, the creation of the Rings of Power and the Ringwraiths, and the early wars of the Rings between Sauron and the Elves. It ended with Sauron's defeat by the Last Alliance of Elves and Men.[T 19]

The 3441 years of the Second Age are mostly unchronicled; there are hints in The Lord of the Rings, and shorter writings fill in some gaps.

"The Tale of Years" in Appendix B of The Lord of the Rings outlines the major events of the Second Age, especially as they relate to the Rings of Power and the events and characters of The Lord of the Rings.[T 19] Appendix A contains genealogies of the royal house of Númenor. Appendix D gives details of the Númenórean calendar, including special intercalation in the years 1000, 2000 and 3000, and notes on how this system of intercalation was disrupted by the designation of S.A. 3442 the first year of the Third Age.[T 20] In addition, several sections of Unfinished Tales deal extensively with Númenor and several of its kings.[T 21] Also, at the end of The Silmarillion, "Akallabêth" recounts the fall of Númenor and its kings, and also the rise of Gondor and Arnor.[T 22]

The Men who had remained faithful were given the island of Númenor, in the middle of the Great Sea, and there they established a powerful kingdom. The White Tree of Númenor was planted in the King's city of Armenelos; and it was said that while that tree stood in the King's courtyard, the reign of Númenor would endure. The Elves were granted pardon for the sins of Fëanor, and were allowed to return home to the Undying Lands.[T 19]

The Númenóreans became great seafarers, and were learned, wise, and had a lifespan beyond other men. At first, they honored the Ban of the Valar, never sailing into the Undying Lands. They went east to Middle-earth and taught the men living there valuable skills. After a time, they became jealous of the Elves for their immortality. Sauron, Morgoth's chief servant, was still active. As Annatar, in disguise he taught the Elves of Eregion the craft of creating Rings of Power. Seven Rings were made for the Dwarves, while Nine were made for Men who later became known as the Ringwraiths. However, he built a stronghold called Barad-dûr and secretly forged the One Ring in the fires of Mount Doom to control the other rings and their bearers. Celebrimbor, a grandson of Fëanor, forged three mighty rings on his own: Vilya, possessed first by the Elven king Gil-galad, then by Elrond; Nenya, wielded by Galadriel; and Narya, given by Celebrimbor to Círdan, who gave it to Gandalf.[T 19]

As soon as Sauron put on the One Ring, the Elves realized that they had been betrayed and removed the Three. (Sauron eventually obtained the Seven and the Nine. While he was unable to suborn the Dwarf ringbearers, he had more success with the Men who bore the Nine; they became the Nazgûl or Ringwraiths.) Sauron then made war on the elves and nearly destroyed them utterly during the Dark Years, but when it seemed defeat was imminent, the Númenóreans joined the battle and completely crushed the forces of Sauron. Sauron never forgot the ruin brought on his armies by the Númenóreans, and made it his goal to destroy them.[T 19]

Towards the end of the age, the Númenóreans became increasingly haughty. Now they sought to dominate other men and to establish kingdoms. Centuries after Tar-Minastir's engagement, when Sauron had largely recovered, Ar-Pharazôn, the last and most powerful of the Kings of Númenor, humbled Sauron – his armies deserting in the face of Númenor's might – and brought him to Númenor as a hostage, although this was Sauron's goal. At this time still beautiful in appearance, Sauron gained Ar-Pharazôn's trust and became high priest in the cult of Melkor. At this time, the Faithful (who still worshipped the one god, Eru Ilúvatar), were persecuted openly by those called the King's Men, and were sacrificed in the name of Melkor. Eventually, Sauron convinced Ar-Pharazôn to invade Aman, promising him that he would thus obtain immortality.[T 19]

Amandil, chief of the Faithful, sailed westward to warn the Valar. His son Elendil and grandsons Isildur and Anárion prepared to flee eastwards, taking with them a seedling of the White Tree of Númenor before Sauron destroyed it, and the palantíri, gifts of the elves. When the King's forces set foot on Aman, the Valar laid down their guardianship of the world and called on Ilúvatar to intervene.[T 19]

The world was changed into a sphere and the continent of Aman was removed, although a sailing route from Middle-earth to Aman, accessible to the Elves but not to mortals, persisted. Númenor was utterly destroyed, as was the fair body of Sauron; however, his spirit returned to Mordor, where he again took up the One Ring, and gathered his strength once more. Elendil, his sons and the remainder of the Faithful sailed to Middle-earth, where they founded the realms in exile of Gondor and Arnor.[T 19]

Sauron arose again and challenged them. The Elves allied with Men to form the Last Alliance of Elves and Men. For seven years, the Alliance laid siege to Barad-dûr, until at last Sauron himself entered the field. He slew Elendil, High King of Gondor and Arnor, and Gil-galad, the last High King of the Noldor in Middle-earth. However, Isildur took up the hilt of Narsil, his father's shattered sword, and cut the One Ring from Sauron's hand. Sauron was defeated, but not utterly destroyed. Afterward, Isildur ignored the counsel of Elrond, and rather than destroy the One Ring in the fires of Mount Doom, he kept it as weregild for his dead father. But the Ring betrayed him and slipped from his finger as he was escaping from an Orc ambush at the Gladden Fields. Isildur was killed by an orc arrow, and the Ring was lost in the Anduin River.[T 19]

Third Age

The Third Age lasted for 3021 years, beginning with the first downfall of Sauron, when he was defeated by the Last Alliance of Elves and Men following the downfall of Númenor and ending with the War of the Ring and final defeat of Sauron, the events narrated in The Lord of the Rings. Virtually the entire history of the Third Age takes place in Middle-earth.[T 23]

The Third Age saw the rise in power of the realms of Arnor and Gondor, and their fall. Arnor was divided into three petty Kingdoms, which fell one by one in the wars with Sauron's vassal kingdom of Angmar, whilst Gondor fell victim to Kin-strife, plague, Wainriders, and Corsairs. In this time, the line of the Kings of Gondor ends, with the House of the Stewards ruling in their stead. Meanwhile, the heirs of Isildur from the fallen kingdom of Arnor wander Middle-earth, aided only by Elrond in Rivendell; but the line of rightful heirs remains unbroken throughout the age.[T 23]

This age was characterized by the waning of the Elves. In the beginning of the Third Age, many Elves left for Valinor because they were disturbed by the recent war. However, Elven kingdoms still survived in Lindon, Lothlórien, and Mirkwood. Rivendell also became a prominent haven for the Elves and other races. Throughout the Age, they chose not to mingle much in the matters of other lands, and only came to the aid of other races in time of war. The Elves devoted themselves to artistic pleasures, and tended to the lands which they occupied. The gradual decline of Elven populations occurred throughout the Age as the rise of Sauron came to dominate Middle-earth. By the end of the Third Age, only fragments of the once-grand Elven civilization survived in Middle-earth.[T 23]

The Wizards arrive around a thousand years[T 23] after the start of this period to aid the Free Peoples, most importantly Gandalf and Saruman. The One Ring was found by Sméagol but, under the power of the Ring and ignorant of its true nature, he retreated with the Ring to a secret life under the Misty Mountains.[T 23]

Middle-earth's devastating Great Plague originated in its vast eastern region, Rhûn, where it caused considerable suffering.[T 24] By the winter of late T.A. 1635 the Plague spread from Rhûn into Wilderland, on the east of Middle-earth's western lands; in Wilderland it killed more than half the population.[T 25] In the following year the Great Plague spread into Gondor and then Eriador. In Gondor the Plague caused many deaths, including king Telemnar, his children, and the White Tree; the population of the capital city Osgiliath was decimated, and government of the kingdom was transferred to Minas Tirith. In Eriador, the nascent Hobbit-realm of the Shire suffered "great loss" in what they called the Dark Plague.[T 23]

The so-called Watchful Peace began in T.A. 2063, when Gandalf went to Dol Guldur and the evil dwelling there (later known to be Sauron) fled to the far east. It lasted until 2460 T.A., when Sauron returned with new strength. During this period Gondor strengthened its borders, keeping a watchful eye on the east, as Minas Morgul was still a threat on their flank and Mordor was still occupied with Orcs. There were minor skirmishes with Umbar. In the north, Arnor was long gone, but the Hobbits of the Shire prospered, getting their first Took Thain, and colonizing Buckland. The Dwarves of Durin's folk under Thorin I abandoned Erebor, and left for the Grey Mountains, where most of their kin now gathered. Meanwhile, Sauron created a strong alliance between the tribes of Easterlings, so that when he returned he had many Men in his service.[T 23]

The main events of The Hobbit occur in T.A. 2941.[T 23]

By the time of The Lord of the Rings, Sauron had recovered, and was seeking the One Ring. The events of the ensuing War of the Ring leading to the end of the Third Age is the subject of The Lord of the Rings, and summarized in Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age. After the defeat of Sauron, Aragorn takes his place as King of the Reunited Kingdom of Arnor and Gondor, restoring the line of Kings from the Stewards of Gondor. Aragorn marries the daughter of Elrond, Arwen, thus for the last time adding Elvish blood to the royal line. As the age ends, Gandalf, Frodo Baggins and many of the remaining Elves of Middle-earth sail from the Grey Havens to Aman.[T 23]

Fourth Age

With the end of the Third Age began the Dominion of Men. Elves were no longer involved in Human affairs, and most Elves leave for Valinor; those that remain behind "fade" and diminish. A similar fate meets the Dwarves: although Erebor becomes an ally of the Reunited Kingdom and there are indications Khazad-dûm is refounded,[T 26] and a colony is established by Gimli in the White Mountains, they disappear from human history. Morgoth's creatures never recover.

Eldarion, son of Aragorn II Elessar and Arwen Evenstar, became King of the Reunited Kingdom in F.A. 120. His father gave him the tokens of his rule, and then gave up his life willingly, as his ancestors had done thousands of years before. Arwen left him to rule alone, passing away to the now-empty land of Lórien where she died.[T 27] Upon the death of Aragorn, Legolas departed Middle-earth for Valinor, taking Gimli with him and ending the Fellowship of the Ring in Middle-earth.[T 28]

Tolkien once considered writing a sequel to The Lord of the Rings, called The New Shadow, which would have taken place in Eldarion's reign, and in which Eldarion deals with his people turning to evil practices - in effect, a repetition of the history of Númenor.[T 29] In a 1972 letter concerning this draft, Tolkien mentioned that Eldarion's reign would have lasted for about 100 years after the death of Aragorn.[T 30] It's stated that his realm would be "great and long-enduring", but also that the lifespan of the royal house was not restored and continued to wane until it was like that of ordinary Men.[T 31]

"Imagined prehistory"

Arda is summed up by the Tolkien scholar Paul H. Kocher as "our own green and solid Earth at some quite remote epoch in the past."[1]

In a letter written in 1958, Tolkien places the beginning of the Fourth Age some 6,000 years in the past:[T 10]

I imagine the gap [since the end of the Third Age] to be about 6000 years; that is we are now at the end of the Fifth Age if the Ages were of about the same length as Second Age and Third Age. But they have, I think, quickened; and I imagine we are actually at the end of the Sixth Age, or in the Seventh."[T 10]

The Tolkien scholar John D. Rateliff writes that one of the "very final passages" of the internal chronology of Lord of the Rings, The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen, ends not just with Arwen's death, but the statement that her grave will remain on the hill of Cerin Amroth in what was Lothlorien "until the world is changed, and all the days of her life are utterly forgotten by men that come after ... and with the passing of [Arwen] Evenstar no more is said in this book of the days of old."[3] Rateliff observes that this points up a "highly unusual" aspect of Tolkien's legendarium among modern fantasy: it is set "in the real world but in an imagined prehistory."[3] As a result, Rateliff explains, Tolkien can build what he likes in that distant past, elves and wizards and hobbits and all the rest, provided that he tears it all down again, so that the modern world can emerge from the wreckage, with nothing but "a word or two, a few vague legends and confused traditions..." to show for it.[3]

Rateliff praises and quotes the scholar of English literature Paul H. Kocher on Tolkien's imagined prehistory and the implied process of fading to lead from fantasy to the modern world:[3]

At the end of his epic Tolkien inserts ... some forebodings of [Middle-earth's] future which will make Earth what it is today ... he shows the initial steps in a long process of retreat or disappearance by which all other intelligent species, which will leave man effectually alone on earth... Ents may still be there in our forests, but what forests have we left? The process of extermination is already well under way in the Third Age, and ... Tolkien bitterly deplores its climax today."[6]

Stuart D. Lee and Elizabeth Solopova make "an attempt at a summary",[7] which runs as follows. The Silmarillion describes events "presented as factual"[7] but taking place before Earth's actual recorded history. What happened is processed through the generations as folk-myths and legends, especially among the (Old) English. Before the Fall of Numenor, the world was flat. In the Fall, it became round; further geological events reshaped the continents into the Earth as it now is. All the same, the old tales survive here and there, resulting in mentions of Dwarves and Elves in real Medieval literature. Thus, Tolkien's imagined mythology "is an attempt to reconstruct our pre-history."[7] Lee and Solopova comment that "Only by understanding this can we fully realize the true scale of his project and comprehend how enormous his achievement was."[7]

The poet W. H. Auden wrote in The New York Times that "no previous writer has, to my knowledge, created an imaginary world and a feigned history in such detail. By the time the reader has finished the trilogy, including the appendices to this last volume, he knows as much about Tolkien's Middle Earth, its landscape, its fauna and flora, its peoples, their languages, their history, their cultural habits, as, outside his special field, he knows about the actual world."[lower-alpha 2][8] The scholar Margaret Hiley comments that Auden's "feigned history" echoes Tolkien's own statement in the foreword to the second edition of Lord of the Rings that he much preferred history, true or feigned, to allegory; and that Middle-earth's history is told in The Silmarillion.[9]

Notes

- Christopher Tolkien called his 12-volume set The History of Middle-earth; scholars such as Brian Rosebury have noted that it makes more sense to call it the history of Arda, as Middle-earth was just one continent, and the early part of the history largely concerns another continent, Aman (Valinor), not to mention the creation and destruction of the island of Númenor.[2]

- Auden only had The Lord of the Rings to go on in 1956, but he commented that "From the appendices readers will get tantalizing glimpses of the First and Second Ages" and hoped that as the "legend of these" had already been written, readers would not have to wait too long for them.[8]

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- The Silmarillion, "Ainulindalë"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 1 "Of the Beginning of Days"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 5 "Of Eldamar and the Princes of the Eldalië"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 7 "Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 8 "Of the Darkening of Valinor"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 6 "Of Fëanor and the Unchaining of Melkor"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 11 "Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 13 "Of the Return of the Noldor"

- Carpenter 1981, #211 to Rhona Beare, 14 October 1958, last footnote

- The Silmarillion, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 17 "Of the Coming of Men into the West"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 18 "Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 20 "Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 22 "Of the Ruin of Doriath"

- The Silmarillion, ch. 23 "Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin"

- Carpenter 1981, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- The Silmarillion, ch. 24 Of the Voyage of Earendil and the War of Wrath

- The Return of the King, Appendix B: The Tale of Years. "The Second Age"

- "After the Downfall in S.A. 3319, the system was maintained by the exiles, but it was much dislocated by the beginning of the Third Age with a new numeration: S.A. 3442 became T.A. 1. By making T.A. 4 a leap year instead of T.A. 3 (S.A. 3444) 1 more short year of only 365 days was intruded"

- Unfinished Tales, part 2: "The Second Age"

- The Silmarillion, "Akallabêth"

- Return of the King, Appendix B: The Tale of Years, "The Third Age"

- The Return of the King, Appendix A part I(iv), p. 328

- Unfinished Tales, part 3 ch. 2(i) pp. 288-289

- The Peoples of Middle-earth: "The Making of Appendix A", '(IV) Durin's Folk', p. 278.

- The Return of the King, Appendix A: The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen

- The Return of the King, Appendix B: Later events concerning the members of the Fellowship of the Ring

- The Peoples of Middle-earth, "The New Shadow"

- Carpenter 1981, #338 to Fr. Douglas Carter, 6 June 1972. "I have written nothing beyond the first few years of the Fourth Age. (Except the beginning of a tale supposed to refer to the end of the reign of Eldarion about 100 years after the death of Aragorn. ...)"

- The Peoples of Middle-earth, "The Heirs of Elendil"

Secondary

- Kocher, Paul (1974) [1972]. Master of Middle-Earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. pp. 8–11. ISBN 0140038779.

- Rosebury, Brian (2003). "Fiction and Poetry, 1914–73". Tolkien: A Cultural Phenomenon. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 89–133. doi:10.1057/9780230599987_4. ISBN 978-1-4039-1263-3.

- West, Richard C. (2006). Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (eds.). 'And All the Days of Her Life Are Forgotten' | 'The Lord of the Rings' as Mythic Prehistory. The Lord of the Rings, 1954-2004 : Scholarship in Honor of Richard E. Blackwelder. Marquette University Press. pp. 67–100. ISBN 0-87462-018-X. OCLC 298788493.

- Day, David (2016). The Battles of Tolkien: An Illustrate Exploration of the Battles of Tolkien's World, and the Sources that Inspired his Work from Myth, Literature and History. Octopus. pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-0-7537-3229-8.

- Day, David (2017). The Heroes of Tolkien: An Exploration of Tolkien's Heroic Characters, and the Sources that Inspired his Work from Myth, Literature and History. Octopus. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7537-3271-7.

- Kocher, Paul H. (1974) [1972]. Master of Middle-Earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0140038779.

- Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-1403946713.

- Auden, W. H. (22 January 1956). "Books: At the End of the Quest, Victory". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Hiley, Margaret Barbara (2006). "Aspects of modernism in the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and Charles Williams". University of Glasgow (PhD Thesis). Retrieved 3 July 2020.

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-31555-7

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955), The Return of the King, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08256-0

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-25730-1

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), Unfinished Tales, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-29917-9

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Peoples of Middle-earth, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-82760-4