Dahomey

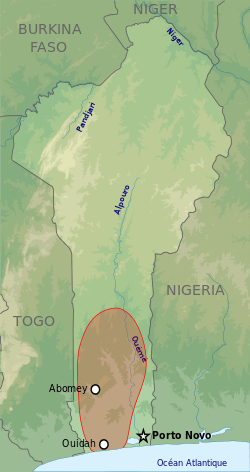

The Kingdom of Dahomey (/dəˈhoʊmi/) was an African kingdom (located within the area of the present-day country of Benin) that existed from about 1600 until 1904, when the last king, Béhanzin, was defeated by the French, and the country was annexed into the French colonial empire. Dahomey developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a regional power in the 18th century by conquering key cities on the Atlantic coast.

Kingdom of Dahomey | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1600–1904 | |||||||

Flag of Béhanzin

Coat of arms

| |||||||

The Kingdom of Dahomey around 1894 | |||||||

| Status | Kingdom, vassal state of the Portuguese Empire (1604–1690), Oyo Empire (1740–1823), French Protectorate (1894–1904) | ||||||

| Capital | Abomey | ||||||

| Common languages | Fon | ||||||

| Religion | Vodun | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Ahosu (King) | |||||||

• c. 1600–1625 (first) | Do-Aklin | ||||||

• 1894–1900 (last) | Agoli-agbo | ||||||

| History | |||||||

| c. 1600 | |||||||

| c. 1620 | |||||||

| 1724–1727 | |||||||

| 1823 | |||||||

• Disestablished | 1904 | ||||||

| Area | |||||||

| 1700[1] | 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi) | ||||||

| Population | |||||||

• 1700[1] | 350,000 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | |||||||

| History of Benin |

|---|

|

| History of the Kingdom of Dahomey |

| Early history |

|

| Modern period |

|

|

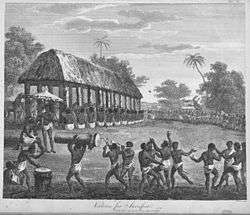

For much of the 18th and 19th centuries, the Kingdom of Dahomey was a key regional state, eventually ending tributary status to the Oyo Empire.[1] The Kingdom of Dahomey was an important regional power that had an organized domestic economy built on conquest and slave labor,[2] significant international trade with Europeans, a centralized administration, taxation systems, and an organized military. Notable in the kingdom were significant artwork, an all-female military unit called the Dahomey Amazons by European observers, and the elaborate religious practices of Vodun with the large festival of the Annual Customs of Dahomey which involved large scale human sacrifice.[3] They traded prisoners, which they captured during wars and raids, and exchanged them with Europeans for goods such as knives, bayonets, firearms, fabrics, and spirits.

Name

The Kingdom of Dahomey was referred to by many different names and has been written in a variety of ways, including Danxome, Danhome, and Fon. The name Fon relates to the dominant ethnic and language group, the Fon people, of the royal families of the kingdom and is how the kingdom first became known to Europeans. The names Dahomey, Danxome, and Danhome all have a similar origin story, which historian Edna Bay says may be a false etymology.[4]

The story goes that Dakodonu, considered the second king in modern kings lists, was granted permission by the Gedevi chiefs, the local rulers, to settle in the Abomey plateau. Dakodonu requested additional land from a prominent chief named Dan (or Da) to which the chief responded sarcastically "Should I open up my belly and build you a house in it?" For this insult, Dakodonu killed Dan and began the construction of his palace on the spot. The name of the kingdom was derived from the incident: Dan=chief dan, xo=Belly, me=Inside of.[5]

History

The Kingdom of Dahomey was established around 1600 by the Fon people who had recently settled in the area (or were possibly a result of intermarriage between the Aja people and the local Gedevi). The foundational king for Dahomey is often considered to be Houegbadja (c. 1645–1685), who built the Royal Palaces of Abomey and began raiding and taking over towns outside of the Abomey plateau.[4]

Kings of Dahomey

| King | Start of Rule | End of Rule |

|---|---|---|

| Do-Aklin (Ganyihessou) | ≈1600 | 1620 |

| Dakodonou | 1620 | 1645 |

| Houégbadja | 1645 | 1680 |

| Akaba | 1680 | 1708 |

| Agaja | 1708 | 1740 |

| Tegbessou(Tegbesu) | 1740 | 1774 |

| Kpengla | 1774 | 1789 |

| Agonglo | 1790 | 1797 |

| Adandozan | 1797 | 1818 |

| Guézo(Ghézo/Gezo) | 1818 | 1858 |

| Glèlè | 1858 | 1889 |

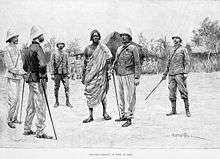

| Béhanzin | 1889 | 1894 |

| Agoli-agbo | 1894 | 1900 |

Rule of Agaja (1708–1740)

King Agaja, Houegbadja's grandson, came to the throne in 1708 and began significant expansion of the Kingdom of Dahomey. This expansion was made possible by the superior military force of King Agaja's Dahomey. In contrast to surrounding regions, Dahomey employed a professional standing army numbering around ten thousand.[7] What the Dahomey lacked in numbers, they made up for in discipline and superior arms. In 1724, Agaja conquered Allada, the origin for the royal family according to oral tradition, and in 1727 he conquered Whydah. This increased size of the kingdom, particularly along the Atlantic coast, and increased power made Dahomey into a regional power. The result was near constant warfare with the main regional state, the Oyo Empire, from 1728 until 1740.[8] The warfare with the Oyo empire resulted in Dahomey assuming a tributary status to the Oyo empire.[9]

Rule of Tegbesu (1740–1774)

Tegbesu, also spelled as Tegbessou, was King of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, from 1740 until 1774. Tegbesu was not the oldest son of King Agaja (1718–1740), but was selected following his father's death after winning a succession struggle with a brother. King Agaja had significantly expanded the Kingdom of Dahomey during his reign, notably conquering Whydah in 1727. This increased the size of the kingdom and increased both domestic dissent and regional opposition. Tegbessou ruled over Dahomey at a point where it needed to increase its legitimacy over those who it had recently conquered. As a result, Tegbesu is often credited with a number of administrative changes in the kingdom in order to establish the legitimacy of the kingdom. The slave trade increased significantly during Tegbessou's reign and began to provide the largest part of the income for the king. In addition, Tegbesu's rule is the one with the first significant kpojito or mother of the leopard with Hwanjile in that role. The kpojito became a prominently important person in Dahomey royalty. Hwanjile, in particular, is said to have changed dramatically the religious practices of Dahomey by creating two new deities and more closely tying worship to that of the king. According to one oral tradition, as part of the tribute owed by Dahomey to Oyo, Agaja had to give to Oyo one of his sons. The story claims that only Hwanjile, of all of Agaja's wives, was willing to allow her son to go to Oyo. This act of sacrifice, according to the oral tradition made Tegbesu, was favored by Agaja. Agaja reportedly told Tegbesu that he was the future king, but his brother Zinga was still the official heir.[10]

End of the kingdom

The kingdom fought the First Franco-Dahomean War and Second Franco-Dahomean War with France. The kingdom was reduced and made a French protectorate in 1894.[11]

In 1904 the area became part of a French colony, French Dahomey.

In 1958 French Dahomey became the self-governing colony called the Republic of Dahomey and gained full independence in 1960. It was renamed in 1975 the People's Republic of Benin and in 1991 the Republic of Benin. The Dahomey kingship exists as a ceremonial role to this day.

Politics

Early writings, predominantly written by European slave traders, often presented the kingdom as an absolute monarchy led by a despotic king. However, these depictions were often deployed as arguments by different sides in the slave trade debates, mainly in the United Kingdom, and as such were probably exaggerations.[4][9] Recent historical work has emphasized the limits of monarchical power in the Kingdom of Dahomey.[5] Historian John C. Yoder, with attention to the Great Council in the kingdom, argued that its activities do not "imply that Dahomey's government was democratic or even that her politics approximated those of nineteenth-century European monarchies. However, such evidence does support the thesis that governmental decisions were molded by conscious responses to internal political pressures as well as by executive fiat."[12] The primary political divisions revolved around villages with chiefs and administrative posts appointed by the king and acting as his representatives to adjudicate disputes in the village.[13]

The king

.jpg)

The King of Dahomey (Ahosu in the Fon language) was the sovereign power of the kingdom. All of the kings were claimed to be part of the Alladaxonou dynasty, claiming descent from the royal family in Allada. Much of the succession rules and administrative structures were created early by Houegbadja, Akaba, and Agaja. Succession through the male members of the line was the norm typically going to the oldest son, but not always.[14] The king was selected largely through discussion and decision in the meetings of the Great Council, although how this operated was not always clear.[4][12] The Great Council brought together a host of different dignitaries from throughout the kingdom yearly to meet at the Annual Customs of Dahomey. Discussions would be lengthy and included members, both men and women, from throughout the kingdom. At the end of the discussions, the king would declare the consensus for the group.[12]

The royal court

Key positions in the King's court included the migan, the mehu, the yovogan, the kpojito (or queen-mother), and later the chacha (or viceroy) of Whydah. The migan (combination of mi-our and gan-chief) was a primary consul for the king, a key judicial figure, and served as the head executioner. The mehu was similarly a key administrative officer who managed the palaces and the affairs of the royal family, economic matters, and the areas to the south of Allada (making the position key to contact with Europeans).

Relations with other states

The relations between Dahomey and other countries were complex and heavily impacted by the Gold trade. The Oyo empire engaged in regular warfare with the kingdom of Dahomey and Dahomey was a tributary to Oyo from 1732 until 1823. The city-state of Porto-Novo, under the protection of Oyo, and Dahomey had a long-standing rivalry largely over control of the Gold trade along the coast. The rise of Abeokuta in the 1840s created another power rivaling Dahomey, largely by creating a safe haven for people from the slave trade.

The last known slave ship that sailed to the United States of America to port in Mobile, Alabama brought a group of 110 slaves from the Dahomey Kingdom, purchased long after the abolition of the international slave trade. Thomas Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves into law on March 2, effective January 1, 1808.[15] The story was mentioned in the newspaper The Tarboro Southerner on July 14, 1860. On July 9, 1860, a schooner called Clotilda, captained by William Foster, arrived in the bay of Mobile, Alabama carrying the last known shipment of slaves to the US from the Dahomey Kingdom. In 1858, a man known as Timothy Meaher made a wager with acquaintances that despite the law banning the slave trade, he could safely bring a load of slaves from Africa.

Describing how he came in possession of the slaves, Captain William Foster wrote in his journal in 1860, "from thence I went to see the King of Dahomey. Having agreeably transacted affairs with the Prince we went to the warehouse where they had in confinement four thousand captives in a state of nudity from which they gave me liberty to select one hundred and twenty-five as mine offering to brand them for me, from which I preemptorily [sic] forbid; commenced taking on cargo of negroes [sic], successfully securing on board one hundred and ten."

A notable descendant of a slave from this ship is Ahmir Khalib Thompson (American music artist known as Questlove). Mr. Thompson's story is depicted in the PBS Television show Finding Your Roots [Season 4, Episode 9].[16]

The Kingdom of Dahomey also sent a diplomatic mission to Brazil, in 1750, while the country was still under Portuguese rule, in order to strengthen diplomatic relations, after an incident which led to the expulsion of Portuguese-Brazilian diplomatic authorities, in 1743. The interest of maintaining these relations was economic, due to slave trade. It is also important to note that Dahomey was the second country - the first being Portugal - to recognize the independence of Brazil in 1822.[17]

Military

The military of the Kingdom of Dahomey was divided into two units: the right and the left. The right was controlled by the migan and the left was controlled by the mehu. At least by the time of Agaja, the kingdom had developed a standing army that remained encamped wherever the king was. Soldiers in the army were recruited as young as seven or eight years old, initially serving as shield carriers for regular soldiers. After years of apprenticeship and military experience, they were allowed to join the army as regular soldiers. To further incentivize the soldiers, each soldier received bonuses paid in cowry shells for each enemy they killed or captured in battle. This combination of lifelong military experience and monetary incentives resulted in a cohesive, well-disciplined military.[18] One European said Agaja's standing army consisted of "elite troops, brave and well-disciplined, led by a prince full of valor and prudence, supported by a staff of experienced officers".[19]

In addition to being well-trained, the Dahomey army under Agaja was also very well armed. The Dahomey army favored imported European weapons as opposed to traditional weapons. For example, they used European flintlock muskets in long-range combat and imported steel swords and cutlasses in close combat. The Dahomey army also possessed twenty-five cannons.

When going into battle, the king would take a secondary position to the field commander with the reason given that if any spirit were to punish the commander for decisions it should not be the king.[13] Unlike other regional powers, the military of Dahomey did not have a significant cavalry (like the Oyo empire) or naval power (which prevented expansion along the coast). The Dahomey Amazons, a unit of all-female soldiers, is one of the most unusual aspects of the military of the kingdom.

Dahomey Amazons

The Dahomean state became widely known for its corps of female soldiers. Their origins are debated; they may have formed from a palace guard or from gbetos (female hunting teams).[20]

They were organized around 1729 to fill out the army and make it look larger in battle, armed only with banners. The women reportedly behaved so courageously they became a permanent corps. In the beginning, the soldiers were criminals pressed into service rather than being executed. Eventually, however, the corps became respected enough that King Ghezo ordered every family to send him their daughters, with the fittest being chosen as soldiers.

Economy

The economic structure of the kingdom was highly intertwined with the political and religious systems and these developed together significantly.[13] The main currency was cowry shells.

Domestic economy

The domestic economy largely focused on agriculture and crafts for local consumption. Until the development of palm oil, very little agricultural or craft goods were traded outside of the kingdom. Markets served a key role in the kingdom and were organized around a rotating cycle of four days with a different market each day (the market type for the day was religiously sanctioned).[13] Agriculture work was largely decentralized and done by most families. However, with the expansion of the kingdom, agricultural plantations began to be a common agricultural method in the kingdom. Craftwork was largely dominated by a formal guild system.[21]

Herskovits recounts a complex tax system in the kingdom, in which officials who represented the king, the tokpe, gathered data from each village regarding their harvest. Then the king set a tax based upon the level of production and village population. In addition, the king's own land and production were taxed.[13] After significant road construction undertaken by the kingdom, toll booths were also established that collected yearly taxes based on the goods people carried and their occupation. Officials also sometimes imposed fines for public nuisance before allowing people to pass.[13]

Religion

| Part of a series on |

| Traditional African religions |

|---|

|

|

Doctrines

|

|

Deities

|

|

Relation with other religions

|

|

The Kingdom of Dahomey shared many religious rituals with surrounding populations; however, it also developed unique ceremonies, beliefs, and religious stories for the kingdom. These included royal ancestor worship and the specific vodun practices of the kingdom.

Royal ancestor worship

Early kings established clear worship of royal ancestors and centralized their ceremonies in the Annual Customs of Dahomey. The spirits of the kings had an exalted position in the land of the dead and it was necessary to get their permission for many activities on earth.[13] Ancestor worship pre-existed the kingdom of Dahomey; however, under King Agaja, a cycle of ritual was created centered on first celebrating the ancestors of the king and then celebrating a family lineage.[5]

The Annual Customs of Dahomey (xwetanu or huetanu in Fon) involved multiple elaborate components and some aspects may have been added in the 19th century. In general, the celebration involved distribution of gifts, human sacrifice, military parades, and political councils. Its main religious aspect was to offer thanks and gain the approval for ancestors of the royal lineage.[5] However, the custom also included military parades, public discussions, gift giving (the distribution of money to and from the king), and human sacrifice and the spilling of blood.[5]

Human sacrifice was an important part of the practice. During the Annual Custom, 500 prisoners would be sacrificed. In addition, when a ruler died, hundreds, to thousands of prisoners would be sacrificed. As many as 4,000 were reported killed In one of these ceremonies in 1727.[22]

Dahomey cosmology

Dahomey had a unique form of West African Vodun that linked together preexisting animist traditions with vodun practices. Oral history recounted that Hwanjile, a wife of Agaja and mother of Tegbessou, brought Vodun to the kingdom and ensured its spread. The primary deity is the combined Mawu-Lisa (Mawu having female characteristics and Lisa having male characteristics) and it is claimed that this god took over the world that was created by their mother Nana-Buluku.[13] Mawu-Lisa governs the sky and is the highest pantheon of gods, but other gods exist in the earth and in thunder. Religious practice organized different priesthoods and shrines for each different god and each different pantheon (sky, earth or thunder). Women made up a significant amount of the priest class and the chief priest was always a descendant of Dakodonou.[4]

Arts

The arts in Dahomey were unique and distinct from the artistic traditions elsewhere in Africa. The arts were substantially supported by the king and his family, had non-religious traditions, assembled multiple different materials, and borrowed widely from other peoples in the region. Common art forms included wood and ivory carving, metalwork (including silver, iron and brass, appliqué cloth, and clay bas-reliefs.[23]

The king was key in supporting the arts and many of them provided significant sums for artists resulting in the unique development, for the region, of a non-religious artistic tradition in the kingdom.[24] Artists were not of a specific class but both royalty and commoners made important artistic contributions.[23] Kings were often depicted in large zoomorphic forms with each king resembling a particular animal in multiple representations.[25]

Suzanne Blier identifies two unique aspects of art in Dahomey: 1. Assemblage of different components and 2. Borrowing from other states. Assemblage of art, involving the combination of multiple components (often of different materials) combined together in a single piece of art, was common in all forms and was the result of the various kings promoting finished products rather than particular styles.[23] This assembling may have been a result of the second feature, which involved the wide borrowing of styles and techniques from other cultures and states. Clothing, cloth work, architecture, and the other forms of art all resemble other artistic representation from around the region.[26]

Much of the artwork revolved around the royalty. Each of the palaces at the Royal Palaces of Abomey contained elaborate bas-reliefs (noundidė in Fon) providing a record of the king's accomplishments.[25] Each king had his own palace within the palace complex and within the outer walls of their personal palace was a series of clay reliefs designed specific to that king. These were not solely designed for royalty and chiefs, temples, and other important buildings had similar reliefs.[24] The reliefs would present Dahomey kings often in military battles against the Oyo or Mahi tribes to the north of Dahomey with their opponents depicted in various negative depictions (the king of Oyo is depicted in one as a baboon eating a cob of corn). Historical themes dominated representation and characters were basically designed and often assembled on top of each other or in close proximity creating an ensemble effect.[24] In addition to the royal depictions in the reliefs, royal members were depicted in power sculptures known as bocio, which incorporated mixed materials (including metal, wood, beads, cloth, fur, feathers, and bone) onto a base forming a standing figure. The bocio are religiously designed to include different forces together to unlock powerful forces.[26] In addition, the cloth appliqué of Dahomey depicted royalty often in similar zoomorphic representation and dealt with matters similar to the reliefs, often the kings leading during warfare.[24]

Dahomey had a distinctive tradition of casting small brass figures of animals or people, which were worn as jewellery or displayed in the homes of the relatively well-off. These figures, which continue to be made for the tourist trade, were relatively unusual in traditional African art in having no religious aspect, being purely decorative, as well as indicative of some wealth.[27] Also unusual, by being so early and clearly provenanced, is a carved wooden tray (not dissimilar to much more recent examples) in Ulm, Germany, which was brought to Europe before 1659, when it was described in a printed catalogue.[28]

In popular culture

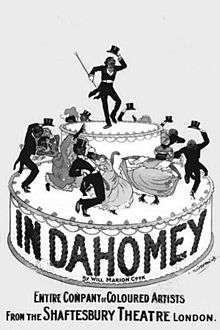

The Kingdom of Dahomey has been depicted in a number of different literary works of fiction or creative nonfiction. In Dahomey (1903) was a successful Broadway musical, the first full-length Broadway musical written entirely by African Americans, in the early 20th century. Novelist Paul Hazoumé's first novel Doguicimi (1938) was based on decades of research into the oral traditions of the Kingdom of Dahomey during the reign of King Ghezo. The anthropologist Judith Gleason wrote a novel, Agõtĩme: Her Legend (1970), centered on one of the wives of a king of Dahomey in the late 18th century, who offends her husband who sells her to slavery in Brazil; she makes a bargain with a vodu (deity), putting her son on the throne of Dahomey and bringing her home. Another novel tracing the background of a slave, this time in the United States, was The Dahomean, or The Man from Dahomey (1971), by the African-American novelist Frank Yerby; its hero is an aristocratic warrior. In the third of George McDonald Fraser's Flashman novels, Flash for Freedom (1971), Flashman dabbles in the slave trade and visits Dahomey. The Viceroy of Ouidah (1980) by Bruce Chatwin is the story of a Brazilian who, hoping to make his fortune from slave trading, sails to Dahomey in 1812, befriending its unbalanced king and coming to a bad end. The book was later adapted into the film Cobra Verde (1987) directed by Werner Herzog. The main character of one of the two parallel stories in Will Do Magic for Small Change (2016) by Andrea Hairston is Kehinde, a Yoruba woman forced into the Dahomean army; she struggles with divided loyalty, and after the fall of Behanzin, joins a French entertainment troupe who intend to exhibit her as an Amazon at the Chicago World's Fair. The Booker prize winning novel Girl, Woman, Other (2019) by Bernardine Evaristo features a character named Amma who writes and directs a play titled 'The Last Amazon of Dahomey'.

Behanzin's resistance to the French attempt to end slave trading and human sacrifice has been central to a number of works. Jean Pliya's first play Kondo le requin (1967), winner of the Grand Prize for African History Literature, tells the story of Behanzin's struggle to maintain the old order. Maryse Condé's novel The Last of the African Kings (1992) similarly focuses on Behanzin's resistance and his exile to the Caribbean.[29] The novel Thread of Gold Beads (2012) by Nike Campbell-Fatoki centers on a daughter of Behanzin; through her eyes, the end of his reign is observed.

See also

References

- Heywood, Linda M.; John K. Thornton (2009). "Kongo and Dahomey, 1660–1815". In Bailyn, Bernard & Patricia L. Denault (ed.). Soundings in Atlantic history: latent structures and intellectual currents, 1500–1830. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Polanyi, Karl (1966). Dahomey and the Slave Trade: An Analysis of an Archaic Economy. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- R. Rummel (1997)"Death by government". Transaction Publishers. p.63. ISBN 1-56000-927-6

- Bay, Edna (1998). Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey. University of Virginia Press.

- Monroe, J. Cameron (2011). "In the Belly of Dan: Space, History, and Power in Precolonial Dahomey". Current Anthropology. 52 (6): 769–798. doi:10.1086/662678.

- Houngnikpo, Mathurin C.; Decalo, Samuel, eds. (2013). Historical Dictionary of Benin. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8108-7373-5.

- Harms, Robert (2002). The Diligent. New York: Basic Books. p. 172.

- Alpern, Stanley B. (1998). "On the Origins of the Amazons of Dahomey". History in Africa. 25: 9–25. doi:10.2307/3172178.

- Law, Robin (1986). "Dahomey and the Slave Trade: Reflections on the Historiography of the Rise of Dahomey". The Journal of African History. 27 (2): 237–267. doi:10.1017/s0021853700036665.

- Bay, Edna (1998). Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey. University of Virginia Press.

- "A Note on the Abomey Protectorate". Africa. 29: 146–155. doi:10.2307/1157517.

- Yoder, John C. (1974). "Fly and Elephant Parties: Political Polarization in Dahomey, 1840–1870". The Journal of African History. 15 (3): 417–432. doi:10.1017/s0021853700013566.

- Herskovits, Melville J. (1967). Dahomey: An Ancient West African Kingdom (Volume I ed.). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Law, Robin (1997). "The Politics of Commercial Transition: Factional Conflict in Dahomey in the Context of the Ending of the Atlantic Slave Trade" (PDF). The Journal of African History. 38 (2): 213–233. doi:10.1017/s0021853796006846. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- United States (1850). The Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America. Charle C. Little and James Brown. pp. 426–430.

- "Season 4 Episode Guide | About | Finding Your Roots". pbs.org. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- Macedo, José Rivair (March 21, 2019). "THE EMBASSY OF DAOMÉ IN SALVADOR (1750): DIPLOMATIC PROTOCOLS AND THE POLITICAL AFFIRMATION OF A STATE IN EXPANSION IN WEST AFRICA". Revista Brasileira de Estudos Africanos. 3 (6). doi:10.22456/2448-3923.86065. ISSN 2448-3923.

- Harms, Robert (2002). The Diligent. New York: Basic Books. p. 172. ISBN 0-465-02872-1.

- Labat. Voyage du chevalier Des Marchais. pp. I:XII.

- Dash, Mike (September 23, 2011). "Dahomey's Women Warriors". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Duignan, Peter; L.H. Gann (1975). "The Pre-colonial economies of sub-saharan Africa". Colonialism in Africa 1870–1960. London: Cambridge. pp. 33–67.

- R. Rummel (1997)"Death by government". Transaction Publishers. p.63. ISBN 1-56000-927-6

- Blier, Suzanne Preston (1988). "Melville J. Herskovits and the Arts of Ancient Dahomey". Anthropology and Aesthetics. 16: 125–142.

- Livingston, Thomas W. (1974). "Ashanti and Dahomean Architectural Bas-Reliefs". African Studies Review. 17 (2): 435–448. doi:10.2307/523643.

- Pique, Francesca; Rainer, Leslie H. (1999). Palace Sculptures of Abomey: History Told on Walls (PDF). Los Angeles: Paul Getty Museum.

- Blier, Suzanne Preston (2004). "The Art of Assemblage: Aesthetic Expression and Social Experience in Danhome". Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics (45): 186–210.

- Willett, Frank (1971). African Art. New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-5002-0364-4.

- Willett, 81–82

- Encyclopedia of African Literature (Gikandi, Simon ed.). London: Routledge. 2003.

Further reading

- Alpern, Stanley B. (1999). Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women Warriors of Dahomey. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-0678-9. In-depth description of the fighting methods of these warriors.

- Bay, Edna G. (1999). Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-1792-4. A historical study of how royal power maintained itself in Dahomey. Bay and Alpern disagree in their interpretation of the women warriors.

- Bay, Edna G. (2008). Asen, Ancestors, and Vodun: Tracing Change in African Art. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-2520-3255-4. Dahomean artistic and cultural history seen through the development (up to the present day) of a single ceremonial object, the asen.

- Law, Robin (2004). Ouidah: The Social History of a West African Slaving ‘Port’, 1727–1892. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1572-6. An academic study of the commercial role of Ouidah in the slave trade.

- Mama, Raouf (1997). Why Goats Smell Bad and Other Stories from Benin. North Haven, CT: Linnet Books. ISBN 0-2080-2469-7. Folktales of the Fon people, including legends of old Dahomey.

- Pique, Francesca; Leslie H. Rainer (2000). Palace Sculptures of Abomey: History Told on Walls. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-8923-6569-2. Heavily-illustrated volume describing the royal palace in Abomey and its bas-reliefs, with a lot of information on the cultural and social history of Dahomey.

External links

- "Museum Theme: The Kingdom of Dahomey". museeouidah.org. Retrieved January 19, 2009.

._-_Dance_of_the_Fon_chiefs.jpg)

._-_The_veteran_amazones(_AHOSI_)_of_the_Fon_king_B%C3%A9hanzin%2C_Son_of_Roi_G%C3%A9l%C3%A9.jpg)