Root of unity

In mathematics, a root of unity, occasionally called a de Moivre number, is any complex number that yields 1 when raised to some positive integer power n. Roots of unity are used in many branches of mathematics, and are especially important in number theory, the theory of group characters, and the discrete Fourier transform.

Roots of unity can be defined in any field. If the characteristic of the field is zero, the roots are complex numbers that are also algebraic integers. For fields with a positive characteristic, the roots belong to a finite field, and, conversely, every nonzero element of a finite field is a root of unity. Any algebraically closed field contains exactly n nth roots of unity, except when n is a multiple of the (positive) characteristic of the field.

General definition

An nth root of unity, where n is a positive integer (i.e. n = 1, 2, 3, …), is a number z satisfying the equation[1][2]

Unless otherwise specified, the roots of unity may be taken to be complex numbers (including the number 1, and the number –1 if n is even, which are complex with a zero imaginary part), and in this case, the nth roots of unity are

However, the defining equation of roots of unity is meaningful over any field (and even over any ring) F, and this allows considering roots of unity in F. Whichever is the field F, the roots of unity in F are either complex numbers, if the characteristic of F is 0, or, otherwise, belong to a finite field. Conversely, every nonzero element in a finite field is a root of unity in that field. See Root of unity modulo n and Finite field for further details.

An nth root of unity is said to be primitive if it is not a mth root of unity for some smaller m, that is if

If n is a prime number, all nth roots of unity, except 1, are primitive.

In the above formula in terms of exponential and trigonometric functions, the primitive nth roots of unity are those for which k and n are coprime integers.

Subsequent sections of this article will comply with complex roots of unity. For the case of roots of unity in fields of nonzero characteristic, see Finite field § Roots of unity. For the case of roots of unity in rings of modular integers, see Root of unity modulo n.

Elementary properties

Every nth root of unity z is a primitive ath root of unity for some a ≤ n, which is the smallest positive integer such that za = 1.

Any integer power of an nth root of unity is also an nth root of unity, as

This is also true for negative exponents. In particular, the reciprocal of an nth root of unity is its complex conjugate, and is also an nth root of unity:

If z is an nth root of unity and a ≡ b (mod n) then za = zb. In fact, by the definition of congruence, a = b + kn for some integer k, and

Therefore, given a power za of z, one has za = zr, where 0 ≤ r < n is the remainder of the Euclidean division of a by n.

Let z be a primitive nth root of unity. Then the powers z, z2, ..., zn−1, zn = z0 = 1 are nth root of unity and are all distinct. (If za = zb where 1 ≤ a < b ≤ n, then zb−a = 1, which would imply that z would not be primitive.) This implies that z, z2, ..., zn−1, zn = z0 = 1 are all of the nth roots of unity, since an nth-degree polynomial equation has at most n distinct solutions.

From the preceding, it follows that, if z is a primitive nth root of unity, then if and only if If z is not primitive then implies but the converse may be false, as shown by the following example. If n = 4, a non-primitive nth root of unity is z = –1, and one has , although

Let z be a primitive nth root of unity. A power w = zk of z is a primitive ath root of unity for

where is the greatest common divisor of n and k. This results from the fact that ka is the smallest multiple of k that is also a multiple of n. In other words, ka is the least common multiple of k and n. Thus

Thus, if k and n are coprime, zk is also a primitive nth root of unity, and therefore there are φ(n) (where φ is Euler's totient function) distinct primitive nth roots of unity. (This implies that if n is a prime number, all the roots except +1 are primitive.)

In other words, if R(n) is the set of all nth roots of unity and P(n) is the set of primitive ones, R(n) is a disjoint union of the P(n):

where the notation means that d goes through all the divisors of n, including 1 and n.

Since the cardinality of R(n) is n, and that of P(n) is φ(n), this demonstrates the classical formula

Group properties

Group of all roots of unity

The product and the multiplicative inverse of two roots of unity are also roots of unity. In fact, if xm = 1 and yn = 1, then (x−1)m = 1, and (xy)k = 1, where k is the least common multiple of m and n.

Therefore, the roots of unity form an abelian group under multiplication. This group is the torsion subgroup of the circle group.

Group of nth roots of unity

The product and the multiplicative inverse of two nth roots of unity are also nth roots of unity. Therefore, the nth roots of unity form a group under multiplication.

Given a primitive nth root of unity ω, the other nth roots are powers of ω. This means that the group of the nth roots of unity is a cyclic group. It is worth remarking that the term of cyclic group originated from the fact that this group is a subgroup of the circle group.

Galois group of the primitive nth roots of unity

Let be the field extension of the rational numbers generated over by a primitive nth root of unity ω. As every nth root of unity is a power of ω, the field contains all nth roots of unity, and is a Galois extension of

If k is an integer, ωk is a primitive nth root of unity if and only if k and n are coprime. In this case, the map

induces an automorphism of , which maps every nth root of unity to its kth power. Every automorphism of is obtained in this way, and these automorphisms form the Galois group of over the field of the rationals.

The rules of exponentiation imply that the composition of two such automorphisms is obtained by multiplying the exponents. It follows that the map

defines a group isomorphism between the units of the ring of integers modulo n and the Galois group of

This shows that this Galois group is abelian, and implies thus that the primitive roots of unity may be expressed in terms of radicals.

Trigonometric expression

De Moivre's formula, which is valid for all real x and integers n, is

Setting x = 2π/n gives a primitive nth root of unity, one gets

but

for k = 1, 2, …, n − 1. In other words,

is a primitive nth root of unity.

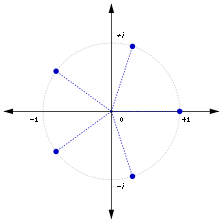

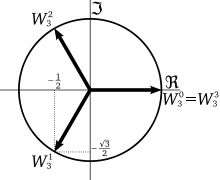

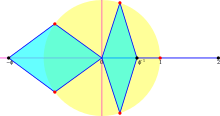

This formula shows that on the complex plane the nth roots of unity are at the vertices of a regular n-sided polygon inscribed in the unit circle, with one vertex at 1. (See the plots for n = 3 and n = 5 on the right.) This geometric fact accounts for the term "cyclotomic" in such phrases as cyclotomic field and cyclotomic polynomial; it is from the Greek roots "cyclo" (circle) plus "tomos" (cut, divide).

which is valid for all real x, can be used to put the formula for the nth roots of unity into the form

It follows from the discussion in the previous section that this is a primitive nth-root if and only if the fraction k/n is in lowest terms, i.e. that k and n are coprime.

Algebraic expression

The nth roots of unity are, by definition, the roots of the polynomial xn − 1, and are thus algebraic numbers. As this polynomial is not irreducible (except for n = 1), the primitive nth roots of unity are roots of an irreducible polynomial of lower degree, called the cyclotomic polynomial, and often denoted Φn. The degree of Φn is given by Euler's totient function, which counts (among other things) the number of primitive nth roots of unity. The roots of Φn are exactly the primitive nth roots of unity.

Galois theory can be used to show that cyclotomic polynomials may be conveniently solved in terms of radicals. (The trivial form is not convenient, because it contains non-primitive roots, such as 1, which are not roots of the cyclotomic polynomial, and because it does not give the real and imaginary parts separately.) This means that, for each positive integer n, there exists an expression built from integers by root extractions, additions, subtractions, multiplications, and divisions (nothing else), such that the primitive nth roots of unity are exactly the set of values that can be obtained by choosing values for the root extractions (k possible values for a kth root). (For more details see § Cyclotomic fields, below.)

Gauss proved that a primitive nth root of unity can be expressed using only square roots, addition, subtraction, multiplication and division if and only if it is possible to construct with compass and straightedge the regular n-gon. This is the case if and only if n is either a power of two or the product of a power of two and Fermat primes that are all different.

If z is a primitive nth root of unity, the same is true for 1/z, and is twice the real part of z. In other words, Φn is a reciprocal polynomial, the polynomial that has r as a root may be deduced from Φn by the standard manipulation on reciprocal polynomials, and the primitive nth roots of unity may be deduced from the roots of by solving the quadratic equation That is, the real part of the primitive root is and its imaginary part is

The polynomial is an irreducible polynomial whose roots are all real. Its degree is a power of two, if and only if n is a product of a power of two by a product (possibly empty) of distinct Fermat primes, and the regular n-gon is constructible with compass and straightedge. Otherwise, it is solvable in radicals, but one are in the casus irreducibilis, that is, every expression of the roots in terms of radicals involves nonreal radicals.

Explicit expressions in low degrees

- For n = 1, the cyclotomic polynomial is Φ1(x) = x − 1 Therefore, the only primitive first root of unity is 1, which is a non-primitive nth root of unity for every n greater than 1.

- As Φ2(x) = x + 1, the only primitive second (square) root of unity is –1, which is also a non-primitive nth root of unity for every even n > 2. With the preceding case, this completes the list of real roots of unity.

- As Φ3(x) = x2 + x + 1, the primitive third (cube) roots of unity, which are the roots of this quadratic polynomial, are

- As Φ4(x) = x2 + 1, the two primitive fourth roots of unity are i and −i.

- As Φ5(x) = x4 + x3 + x2 + x + 1, the four primitive fifth roots of unity are the roots of this quartic polynomial, which may be explicitly solved in terms of radicals, giving the roots

- where may take the two values 1 and –1 (the same value in the two occurrences).

- As Φ6(x) = x2 − x + 1, there are two primitive sixth roots of unity, which are the negatives (and also the square roots) of the two primitive cube roots:

- As 7 is not a Fermat prime, the seventh roots of unity are the first that require cube roots. There are 6 primitive seventh roots of unity, which are pairwise complex conjugate. The sum of a root and its conjugate is twice its real part. These three sums are the three real roots of the cubic polynomial and the primitive seventh roots of unity are

- where r runs over the roots of the above polynomial. As for every cubic polynomial, these roots may be expressed in terms of square and cube roots. However, as these three roots are all real, this is casus irreducibilis, and any such expression involves non-real cube roots.

- As Φ8(x) = x4 + 1, the four primitive eighth roots of unity are the square roots of the primitive fourth roots, ±i. They are thus

- See heptadecagon for the real part of a 17th root of unity.

Periodicity

If z is a primitive nth root of unity, then the sequence of powers

- … , z−1, z0, z1, …

is n-periodic (because z j + n = z j⋅z n = z j⋅1 = z j for all values of j), and the n sequences of powers

- sk: … , z k⋅(−1), z k⋅0, z k⋅1, …

for k = 1, … , n are all n-periodic (because z k⋅(j + n) = z k⋅j). Furthermore, the set {s1, … , sn} of these sequences is a basis of the linear space of all n-periodic sequences. This means that any n-periodic sequence of complex numbers

- … , x−1 , x0 , x1, …

can be expressed as a linear combination of powers of a primitive nth root of unity:

for some complex numbers X1, … , Xn and every integer j.

This is a form of Fourier analysis. If j is a (discrete) time variable, then k is a frequency and Xk is a complex amplitude.

Choosing for the primitive nth root of unity

allows xj to be expressed as a linear combination of cos and sin:

This is a discrete Fourier transform.

Summation

Let SR(n) be the sum of all the nth roots of unity, primitive or not. Then

This is an immediate consequence of Vieta's formulas. In fact, the nth roots of unity being the roots of the polynomial Xn – 1, their sum is the coefficient of degree n – 1, which is either 1 or 0 according whether n = 1 or n > 1.

Alternatively, for n = 1 there is nothing to prove. For n > 1 there exists a root z ≠ 1. Since the set S of all the nth roots of unity is a group, z S = S, so the sum satisfies z SR(n) = SR(n), whence SR(n) = 0.

Let SP(n) be the sum of all the primitive nth roots of unity. Then

where μ(n) is the Möbius function.

In the section Elementary properties, it was shown that if R(n) is the set of all nth roots of unity and P(n) is the set of primitive ones, R(n) is a disjoint union of the P(n):

This implies

Applying the Möbius inversion formula gives

In this formula, if d < n, then SR(n/d) = 0, and for d = n: SR(n/d) = 1. Therefore, SP(n) = μ(n).

This is the special case cn(1) of Ramanujan's sum cn(s), defined as the sum of the sth powers of the primitive nth roots of unity:

Orthogonality

From the summation formula follows an orthogonality relationship: for j = 1, … , n and j′ = 1, … , n

where δ is the Kronecker delta and z is any primitive nth root of unity.

The n × n matrix U whose (j, k)th entry is

defines a discrete Fourier transform. Computing the inverse transformation using gaussian elimination requires O(n3) operations. However, it follows from the orthogonality that U is unitary. That is,

and thus the inverse of U is simply the complex conjugate. (This fact was first noted by Gauss when solving the problem of trigonometric interpolation). The straightforward application of U or its inverse to a given vector requires O(n2) operations. The fast Fourier transform algorithms reduces the number of operations further to O(n log n).

Cyclotomic polynomials

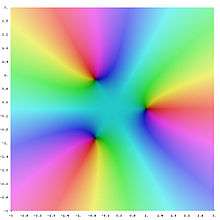

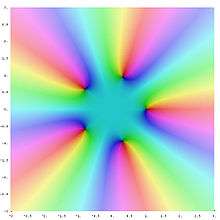

The zeroes of the polynomial

are precisely the nth roots of unity, each with multiplicity 1. The nth cyclotomic polynomial is defined by the fact that its zeros are precisely the primitive nth roots of unity, each with multiplicity 1.

where z1, z2, z3, … ,zφ(n) are the primitive nth roots of unity, and φ(n) is Euler's totient function. The polynomial Φn(z) has integer coefficients and is an irreducible polynomial over the rational numbers (i.e., it cannot be written as the product of two positive-degree polynomials with rational coefficients). The case of prime n, which is easier than the general assertion, follows by applying Eisenstein's criterion to the polynomial

and expanding via the binomial theorem.

Every nth root of unity is a primitive dth root of unity for exactly one positive divisor d of n. This implies that

This formula represents the factorization of the polynomial zn − 1 into irreducible factors.

Applying Möbius inversion to the formula gives

where μ is the Möbius function. So the first few cyclotomic polynomials are

- Φ1(z) = z − 1

- Φ2(z) = (z2 − 1)⋅(z − 1)−1 = z + 1

- Φ3(z) = (z3 − 1)⋅(z − 1)−1 = z2 + z + 1

- Φ4(z) = (z4 − 1)⋅(z2 − 1)−1 = z2 + 1

- Φ5(z) = (z5 − 1)⋅(z − 1)−1 = z4 + z3 + z2 + z + 1

- Φ6(z) = (z6 − 1)⋅(z3 − 1)−1⋅(z2 − 1)−1⋅(z − 1) = z2 − z + 1

- Φ7(z) = (z7 − 1)⋅(z − 1)−1 = z6 + z5 + z4 + z3 + z2 +z + 1

- Φ8(z) = (z8 − 1)⋅(z4 − 1)−1 = z4 + 1

If p is a prime number, then all the pth roots of unity except 1 are primitive pth roots, and we have

Substituting any positive integer ≥ 2 for z, this sum becomes a base z repunit. Thus a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for a repunit to be prime is that its length be prime.

Note that, contrary to first appearances, not all coefficients of all cyclotomic polynomials are 0, 1, or −1. The first exception is Φ105. It is not a surprise it takes this long to get an example, because the behavior of the coefficients depends not so much on n as on how many odd prime factors appear in n. More precisely, it can be shown that if n has 1 or 2 odd prime factors (e.g., n = 150) then the nth cyclotomic polynomial only has coefficients 0, 1 or −1. Thus the first conceivable n for which there could be a coefficient besides 0, 1, or −1 is a product of the three smallest odd primes, and that is 3⋅5⋅7 = 105. This by itself doesn't prove the 105th polynomial has another coefficient, but does show it is the first one which even has a chance of working (and then a computation of the coefficients shows it does). A theorem of Schur says that there are cyclotomic polynomials with coefficients arbitrarily large in absolute value. In particular, if where are odd primes, and t is odd, then 1 − t occurs as a coefficient in the nth cyclotomic polynomial.[3]

Many restrictions are known about the values that cyclotomic polynomials can assume at integer values. For example, if p is prime, then d ∣ Φp(d) if and only d ≡ 1 (mod p).

Cyclotomic polynomials are solvable in radicals, as roots of unity are themselves radicals. Moreover, there exist more informative radical expressions for nth roots of unity with the additional property[4] that every value of the expression obtained by choosing values of the radicals (for example, signs of square roots) is a primitive nth root of unity. This was already shown by Gauss in 1797.[5] Efficient algorithms exist for calculating such expressions.[6]

Cyclic groups

The nth roots of unity form under multiplication a cyclic group of order n, and in fact these groups comprise all of the finite subgroups of the multiplicative group of the complex number field. A generator for this cyclic group is a primitive nth root of unity.

The nth roots of unity form an irreducible representation of any cyclic group of order n. The orthogonality relationship also follows from group-theoretic principles as described in character group.

The roots of unity appear as entries of the eigenvectors of any circulant matrix, i.e. matrices that are invariant under cyclic shifts, a fact that also follows from group representation theory as a variant of Bloch's theorem.[7] In particular, if a circulant Hermitian matrix is considered (for example, a discretized one-dimensional Laplacian with periodic boundaries[8]), the orthogonality property immediately follows from the usual orthogonality of eigenvectors of Hermitian matrices.

Cyclotomic fields

By adjoining a primitive nth root of unity to one obtains the nth cyclotomic field This field contains all nth roots of unity and is the splitting field of the nth cyclotomic polynomial over The field extension has degree φ(n) and its Galois group is naturally isomorphic to the multiplicative group of units of the ring

As the Galois group of is abelian, this is an abelian extension. Every subfield of a cyclotomic field is an abelian extension of the rationals. It follows that every nth root of unity may be expressed in term of k-roots, with various k not exceeding φ(n). In these cases Galois theory can be written out explicitly in terms of Gaussian periods: this theory from the Disquisitiones Arithmeticae of Gauss was published many years before Galois.[9]

Conversely, every abelian extension of the rationals is such a subfield of a cyclotomic field – this is the content of a theorem of Kronecker, usually called the Kronecker–Weber theorem on the grounds that Weber completed the proof.

Relation to quadratic integers

For n = 1, 2, both roots of unity 1 and −1 are integers.

For three values of n, the roots of unity are quadratic integers:

- For n = 3, 6 they are Eisenstein integers (D = −3).

- For n = 4 they are Gaussian integers (D = −1): see imaginary unit.

For four other values of n, the primitive roots of unity are not quadratic integers, but the sum of any root of unity with its complex conjugate (also an nth root of unity) is a quadratic integer.

For n = 5, 10, none of the non-real roots of unity (which satisfy a quartic equation) is a quadratic integer, but the sum z + z = 2 Rez of each root with its complex conjugate (also a 5th root of unity) is an element of the ring Z[1 + √5/2] (D = 5). For two pairs of non-real 5th roots of unity these sums are inverse golden ratio and minus golden ratio.

For n = 8, for any root of unity z + z equals to either 0, ±2, or ±√2 (D = 2).

For n = 12, for any root of unity, z + z equals to either 0, ±1, ±2 or ±√3 (D = 3).

See also

- Argand system

- Circle group, the unit complex numbers

- Group scheme of roots of unity

- Dirichlet character

- Ramanujan's sum

- Kummer ring

- Witt vector

- Teichmüller character

Notes

- Hadlock, Charles R. (2000). Field Theory and Its Classical Problems, Volume 14. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-0-88385-032-9.

- Lang, Serge (2002). "Roots of unity". Algebra. Springer. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-0-387-95385-4.

- Emma Lehmer, On the magnitude of the coefficients of the cyclotomic polynomial, Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 42 (1936), no. 6, pp. 389–392.

- Landau, Susan; Miller, Gary L. (1985). "Solvability by radicals is in polynomial time". Journal of Computer and System Sciences. 30 (2): 179–208. doi:10.1016/0022-0000(85)90013-3.

- Gauss, Carl F. (1965). Disquisitiones Arithmeticae. Yale University Press. pp. §§359–360. ISBN 0-300-09473-6.

- Weber, Andreas; Keckeisen, Michael. "Solving Cyclotomic Polynomials by Radical Expressions" (PDF). Retrieved 22 June 2007.

- T. Inui, Y. Tanabe, and Y. Onodera, Group Theory and Its Applications in Physics (Springer, 1996).

- Gilbert Strang, "The discrete cosine transform," SIAM Review 41 (1), 135–147 (1999).

- The Disquisitiones was published in 1801, Galois was born in 1811, died in 1832, but wasn't published until 1846.

References

- Lang, Serge (2002), Algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 211 (Revised third ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-95385-4, MR 1878556, Zbl 0984.00001

- Milne, James S. (1998). "Algebraic Number Theory". Course Notes.

- Milne, James S. (1997). "Class Field Theory". Course Notes.

- Neukirch, Jürgen (1999). Algebraic Number Theory. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften. 322. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-65399-8. MR 1697859. Zbl 0956.11021.

- Neukirch, Jürgen (1986). Class Field Theory. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-15251-2.

- Washington, Lawrence C. (1997). Cyclotomic fields (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-94762-0.

- Derbyshire, John (2006). "Roots of Unity". Unknown Quantity. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0-309-09657-X.