Crystal, Colorado

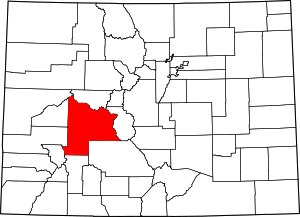

Crystal (also known as Crystal City) is a ghost town on the upper Crystal River in Gunnison County, Colorado, United States. It is located in the Elk Mountains along a four-wheel-drive road 6 miles (9.7 km) east of Marble and 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Crested Butte. Crystal was a mining camp established in 1881 and after several decades of robust existence, was all but abandoned by 1917. Many buildings still stand in Crystal, but its few residents live there only in the summer.[2][3]

Crystal, Colorado | |

|---|---|

The Crystal Club building, 2015 | |

Crystal  Crystal | |

| Coordinates: 39°03′33″N 107°06′04″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Colorado |

| County | Gunnison |

| Elevation | 8,950 ft (2,728 m) |

| GNIS feature ID | 175564 |

History

In 1874, geologist Sylvester Richardson discovered promising deposits of silver near the confluence of the North Fork and South Fork of the Crystal River in Gunnison County. In the years that followed, the Ute native american tribe was removed from the area and prospectors began mining operations, creating a new mining camp in 1880.[4] A year later, on August 6, 1881, the Gunnison County court held a session and voted for the incorporation of Crystal City, which was made official on June 8, 1881.[5] At its height of prosperity in the mid-1880s, Crystal had over 500 residents, a post office, a newspaper (the Crystal River Current which was later replaced by The Silver Lance), a pool hall, the Crystal Club (a popular and exclusive men's club), a barber shop, saloons, and hotels.[2][3]

During the 1880s and 1890s, when miners began to inhabit Crystal and the surrounding area, fire was used to clear the land in order to begin mining. Thousands of acres were set ablaze removing old growth trees and altering the pattern of vegetation in the area. This allowed for several mines near crystal to prove productive, among the largest being the Black Queen, Lead King, and Sheep Mountain Tunnel. Silver, lead, and zinc were the primary metals produced, but getting the ore out of the valley was a continuing problem. The nearest rail stations were in Crested Butte and Carbondale, 20 miles (32 km) and 34 miles (55 km) distant, respectively. These routes out of Crystal were, in places, not much more than a trail. While work to improve the paths continued years after the establishment of Crystal, the routes never amounted to more than narrow wagon trails during the years the mines shipped ore. As a result, the majority of the ore was taken to the stations by jack train with up to 100 mules.[2][3][6]

The remoteness of Crystal hindered its success. The transport of ore out to the depots in Crested Butte and Carbondale (via Marble) and the resupply of basic necessities and mail into Crystal were a challenge in the snow-free months and difficult to impossible during the winter. Deep snow and late-lying snow drifts were hindrances and avalanches, rock slides, and wet, slick ledge roads were dangerous and sometimes deadly. Transportation difficulties cut into profits and by 1889 Crystal was in decline with the winter population being less than 100.[2][3]

Despite the silver panic of 1893 , while many other mines throughout the country were shutting down, Crystal still supported multiple mining operations. In fact that same year, the historic Crystal Mill was built by George C. Eaton and B.S Phillips. The pair were promoters of the Sheep Mountain Tunnel and Mining Company, and the building, then known as the Sheep Mountain Tunnel Mill, was built to supply power to that and surrounding mines. Water from the Crystal River was dammed and used to provide electricity for air drills and ventilation for miners. The powerhouse used the flow of the Crystal River to power an air compressor, and the compressed air was piped to the mines to run pneumatic drills. This system was so efficient that soon after, a stamp mill was built to crush and concentrate the silver ore for shipping. This innovation saved the mining operations for a few years, but crystal continued to decline and soon the population had dwindled to eight by the year of 1915. in 1917 the mines and the Sheep Mountain powerhouse were closed, and Crystal was largely vacated. [2][3][7]

In 1938, after many years of Crystal having been abandoned, Emmet Shaw Gould of Aspen, CO traveled to Crystal searching for ore to run through a recently purchased mill. he bought several mining claims along with the city lots with the cabins still standing. The area stayed in his possession, though it was never made profitable again by means of mining. Eventually, ownership was transferred to one of Gould's daughters, Dorothy Tidwell of Treasure Mountain Ranch, Inc. In 1985, while owned by Tidwell, Crystal was nominated and selected for a place in the National Register of Historic Places Inventory by the Gunnison County Courthouse. [8]

Physiology

Climate

The highest average temperature is 68.1 degrees Fahrenheit, while the lowest average temperature is 41.6 degrees Fahrenheit. [9] In July the average temperature is 56.8 degrees Fahrenheit, and in January the average temperature is 13.6 degrees Fahrenheit.[6] The highest recorded temperature in the area was 106 degrees Fahrenheit on July 21, 2005. The lowest recorded temperature was -23 degrees Fahrenheit on January 13, 1963. There are an average of 90 days each year with temperatures above or equal to 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and 140 days a year with recorded temperatures below or equal to 32 degrees Fahrenheit.[9] The average annual rainfall in inches is 10.63, while yearly annual snowfall in inches is 45. [10]

Parent Rock

The rock in the Elk Mountain Range in the area surrounding Crystal is composed primarily of (90%) sedimentary material, including mostly course elastics, shale, and limestone. The last 10% is mostly igneous rock. The Maroon Mountains formations (which are the closest notable mountains to the valley town of Crystal) are composed of mostly sandstone and siltstone, which are course elastic rocks and are exposed for the most part. Fine elastic rocks cover a fifth of Crystal. Glacial remain and out-wash created the sandy loam material which fill the valleys in the area, including the bottom of the Crystal River which runs through the valley in Crystal and surrounding towns.[6]

Topography

The elevation of Crystal is centered at 8,950 ft, however the area in and around crystal ranges from 8,500 ft to peaks of 13,500 ft. The land is well drained, and the rock types such as limestone create very steep slopes common in the Rocky Mountains. The area is described as having classically alpine terrain in characteristics, and the sources of the areas streams are mainly glacial cirques. Barren parts of the mountains that are at elevations low enough to support vegetation growth are primarily unable to support much vegetation due to the steep slopes and the large accumulation of shale rocks.[2][6]

Overview

Crystal is vacated in the winter but there are a few summer residents. The town does see visitors, most passing through to recreate in the area. The upper Crystal River Valley is nestled between two wilderness areas: the Maroon Bells–Snowmass Wilderness to the north and the Raggeds Wilderness to the south. Photography, hiking, peak bagging, mountain biking, and four-wheel-drive and off-highway vehicle touring are common activities. Fly fishing and hunting (deer and elk) are also popular.[11]

Today Crystal is best known for one of the most photographed historic sites in Colorado, the Crystal Mill, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

Transportation

Gunnison County Road 3 connects Crystal to Marble. Much of the road is a rocky shelf road, suitable for four-wheel drive only.

Forest Road 317 (a.k.a. Gothic Road) connects Crystal to Crested Butte via Schofield Pass. It traverses the Devils Punchbowl, considered among the most dangerous four-wheel drive trails in the state.[12]

Gallery

Crystal mill (foreground) and town (behind), 1890s

Crystal mill (foreground) and town (behind), 1890s.jpg) Crystal mill, 2012

Crystal mill, 2012- Cabin in Crystal, 2015

The Crystal Mill, among the Elk Mountains in 2016. Crystal, CO

The Crystal Mill, among the Elk Mountains in 2016. Crystal, CO

See also

Notes

- "Crystal". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Brown, Robert (1968). Ghost Towns of the Colorado Rockies. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers. LCCN 68-010099.

- Vandenbusche, Duane (1980). The Gunnison Country. Gunnison, Colorado: B&B Printers. LCCN 80-070455.

- Yongli (2017-05-19). "Crystal Mill". coloradoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Waller, Marion S (August 30, 1881). "Incorporation Notice". Gunnison Daily News Democrat. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Langenheim, J. H. (1962). "Vegetation and environmental patterns in the Crested Butte area, Gunnison County, Colorado". Ecological Monographs. 32: 249–285. doi:10.2307/1942400 – via Digital Commons.

- United States. Department of Agriculture. Forest Service. The Crystal Mill. By Oscar McCollum. 1996. Print https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5187127.pdf

- United States. Department of the Interior. National Park Service. National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form. By Tracey Thrasher Daily. 1985. 1 April, 1985. Print

- "National Weather Service Forecast Office". w2.weather.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Climate Gunnison - Colorado and Weather averages Gunnison". www.usclimatedata.com. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Activities". Marble Crystal River Chamber. Archived from the original on 2015-08-26. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- "Schofield Pass Road # 317" (PDF). Four-Wheel Driving: Colorado. United States Forest Service. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

External links

- Town of Crystal, Marble Tourism Association

- On the wild road to Crystal Mill: Colorado's photographic gem, The Gazette

- Crystal River Current which was later replaced by The Silver Lance