Cross-cultural communication

Cross-cultural communication is a field of study that looks at how people from differing cultural backgrounds communicate, in similar and different ways among themselves, and how they endeavor to communicate across cultures. Intercultural communication is a related field of study.[1]

Origins and culture

During the Cold War, the economy of the United States was largely self-contained because the world was polarized into two separate and competing powers: the East and the West. However, changes and advancements in economic relationships, political systems, and technological options began to break down old cultural barriers. Business transformed from individual-country capitalism to global capitalism. Thus, the study of cross-cultural communication was originally found within businesses and government, both seeking to expand globally. Businesses began to offer language training to their employees and programs were developed to train employees to understand how to act when abroad. With this also came the development of the Foreign Service Institute, or FSI, through the Foreign Service Act of 1946, where government employees received training and prepared for overseas posts.[2] There began also implementation of a “world view” perspective in the curriculum of higher education.[3] In 1974, the International Progress Organization, with the support of UNESCO and under the auspices of Senegalese President Léopold Sédar Senghor, held an international conference on "The Cultural Self-comprehension of Nations" (Innsbruck, Austria, 27–29 July 1974) which called upon United Nations member states "to organize systematic and global comparative research on the different cultures of the world" and "to make all possible efforts for a more intensive training of diplomats in the field of international cultural co-operation ... and to develop the cultural aspects of their foreign policy."[4]

There has become an increasing pressure for universities across the world to incorporate intercultural and international understanding and knowledge into the education of their students.[5] International literacy and cross-cultural understanding have become critical to a country's cultural, technological, economic, and political health. It has become essential for universities to educate, or more importantly, “transform”, to function effectively and comfortably in a world characterized by close, multi-faceted relationships and permeable borders. Students must possess a certain level of global competence to understand the world they live in and how they fit into this world. This level of global competence starts at ground level- the university and its faculty- with how they generate and transmit cross-cultural knowledge and information to students.[6]

Interdisciplinary orientation

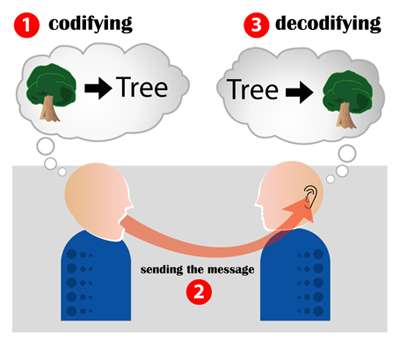

Cross-cultural communication endeavors to bring together the relatively unrelated fields of cultural anthropology with established areas of communication. At its core, cross-cultural communication involves understanding the ways in which culturally distinct individuals communicate with each other. Its charge is to also produce some guidelines with which people from different cultures can better communicate with each other.

Cross-cultural communication requires an interdisciplinary approach. It involves literacy in fields such as anthropology, cultural studies, psychology and communication. The field has also moved both toward the treatment of interethnic relations, and toward the study of communication strategies used by co-cultural populations, i.e., communication strategies used to deal with majority or mainstream populations.

The study of languages other than one's own can serve not only to help one understand what we as humans have in common, but also to assist in the understanding of the diversity which underlines our languages' methods of constructing and organizing knowledge. Such understanding has profound implications with respect to developing a critical awareness of social relationships. Understanding social relationships and the way other cultures work is the groundwork of successful globalization business affairs.

Language socialization can be broadly defined as “an investigation of how language both presupposes and creates anew, social relations in cultural context”.[7] It is imperative that the speaker understands the grammar of a language, as well as how elements of language are socially situated in order to reach communicative competence. Human experience is culturally relevant, so elements of language are also culturally relevant.[7]:3 One must carefully consider semiotics and the evaluation of sign systems to compare cross-cultural norms of communication.[7]:4 There are several potential problems that come with language socialization, however. Sometimes people can over-generalize or label cultures with stereotypical and subjective characterizations. Another primary concern with documenting alternative cultural norms revolves around the fact that no social actor uses language in ways that perfectly match normative characterizations.[7]:8 A methodology for investigating how an individual uses language and other semiotic activity to create and use new models of conduct and how this varies from the cultural norm should be incorporated into the study of language socialization.[7]:11,12

Global rise

With increasing globalization and international trade, it is unavoidable that different cultures will meet, conflict, and blend together. People from different culture find it is difficult to communicate not only due to language barriers, but also are affected by culture styles.[8] For instance, in individualistic cultures, such as in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe, an independent figure or self is dominant. This independent figure is characterized by a sense of self relatively distinct from others and the environment. In interdependent cultures, usually identified as Asian, Latin American, African, and Southern European cultures, an interdependent figure of self is dominant. There is a much greater emphasis on the interrelatedness of the individual to others and the environment; the self is meaningful only (or primarily) in the context of social relationships, duties, and roles. In some degree, the effect brought by cultural difference override the language gap. This culture style difference contributes to one of the biggest challenges for cross-culture communication. Effective communication with people of different cultures is especially challenging. Cultures provide people with ways of thinking—ways of seeing, hearing, and interpreting the world. Thus the same words can mean different things to people from different cultures, even when they speak the "same" language. When the languages are different, and translation has to be used to communicate, the potential for misunderstandings increases. The study of cross-cultural communication is a global research area. As a result, cultural differences in the study of cross-cultural communication can already be found. For example, cross-cultural communication is generally considered part of communication studies in the US, but is emerging as a sub-field of applied linguistics in the UK.

Incorporation into college programs

The application of cross-cultural communication theory to foreign language education is increasingly appreciated around the world. Cross-cultural communication classes can now be found within foreign language departments of some universities, while other schools are placing cross-cultural communication programs in their departments of education.

With the increasing pressures and opportunities of globalization, the incorporation of international networking alliances has become an “essential mechanism for the internationalization of higher education”.[9] Many universities from around the world have taken great strides to increase intercultural understanding through processes of organizational change and innovations. In general, university processes revolve around four major dimensions which include: organizational change, curriculum innovation, staff development, and student mobility.[10] Ellingboe emphasizes these four major dimensions with his own specifications for the internationalization process. His specifications include: (1) college leadership; (2) faculty members' international involvement in activities with colleagues, research sites, and institutions worldwide; (3) the availability, affordability, accessibility, and transferability of study abroad programs for students; (4) the presence and integration of international students, scholars, and visiting faculty into campus life; and (5) international co-curricular units (residence halls, conference planning centers, student unions, career centers, cultural immersion and language houses, student activities, and student organizations).[6]

Above all, universities need to make sure that they are open and responsive to changes in the outside environment. In order for internationalization to be fully effective, the university (including all staff, students, curriculum, and activities) needs to be current with cultural changes, and willing to adapt to these changes.[11] As stated by Ellingboe, internationalization “is an ongoing, future-oriented, multidimensional, interdisciplinary, leadership-driven vision that involves many stakeholders working to change the internal dynamics of an institution to respond and adapt appropriately to an increasingly diverse, globally focused, ever-changing external environment".[12] New distance learning technologies, such as interactive teleconferencing, enable students located thousands of miles apart to communicate and interact in a virtual classroom.[13]

Research has indicated that certain themes and images such as children, animals, life cycles, relationships, and sports can transcend cultural differences, and may be used in international settings such as traditional and online university classrooms to create common ground among diverse cultures (Van Hook, 2011).[14]

Many Master of Science in Management programs have an internationalization specialization which may place a focus on cross-cultural communication. For example, the Ivey Business School has a course titled Cross Cultural Management.[15]

Cross cultural communication gives opportunities to share ideas, experiences, and different perspectives and perception by interacting with local people.

Challenges in cross-language qualitative research

Cross-language research refers to research involving two or more languages. Specifically, it can refer to: 1) researchers working with participants in a language that they are not fluent in, or; 2) researchers working with participants utilizing a language that is neither of their native languages, or; 3) translation of research or findings in another language, or; 4) researchers and participants speak the same language (not English). However, the research process and findings are directed to an English-speaking audience.

Cross-language issues are of growing concern in research of all methodological forms, but they raise particular concerns for qualitative research. Qualitative researchers seek to develop a comprehensive understanding of human behavior, using inductive approaches to investigate the meanings people attribute to their behavior, actions, and interactions with others. In other words, qualitative researchers seek to gain insights into life experiences by exploring the depth, richness, and complexity inherent to human phenomenon. To gather data, qualitative researchers use direct observation and immersion, interviews, open-ended surveys, focus groups, content analysis of visual and textual material, and oral histories. Qualitative research studies involving cross-language issues are particularly complex in that they require investigating meanings, interpretations, symbols, and the processes and relations of social life.

Although a range of scholars have dedicated their attention to challenges in conducting qualitative studies in cross-cultural contexts,[16] no methodological consensus has emerged from these studies. For instance, Edwards[17] noticed how the inconsistent or inappropriate use of translators or interpreters can threaten the trustworthiness of cross-language qualitative research and the applicability of the translated findings on participant populations. Researchers who fail to address the methodological issues translators/interpreters present in a cross-language qualitative research can decrease the trustworthiness of the data as well as compromise the overall rigor of the study[17][18] Temple and Edwards[19] also describe the important role of translation in research, pointing out that language is not just a tool or technical label for conveying concepts; Indeed, language incorporates values and beliefs and carries cultural, social, and political meanings of a particular social reality that may not have a conceptual equivalence in the language into which will be translated[20]. In the same veing, it has also been noted that the same words can mean different things in different cultures. For instance, as Temple et al.[19] observe, the words we choose matter. Thus, it is crucial to give attention to how researchers describe the use of translators and/or interpreters since it reflects their competence in addressing language as a methodological issue.

Historical discussion of cross-language issues and qualitative research

In 1989, Saville-Troike[21] was one of the first to turn to apply the use of qualitative research (in the form of ethnographic investigation) to the topic of cross-cultural communication. Using this methodology, Saville-Troike demonstrated that for successful communication to take place, a person must have the appropriate linguistic knowledge, interaction skills, and cultural knowledge. In a cross-cultural context, one must be aware of differences in norms of interaction and interpretation, values and attitudes, as well as cognitive maps and schemata.[21] Regarding cross-cultural interviews, subsequently Stanton[22] argued in 1996 that in order to avoid misunderstandings, the interviewer should try to walk in the other person’s shoes. In other words, the interviewer needed to pay attention to the point of view of the interviewee, a notion dubbed as “connected knowing," which refers to a clear and undistorted understanding of the perspective of the interviewee.[22]

Relationship between cross-language issues and qualitative research

As one of the primary methods for collecting rich and detailed information in qualitative research, interviews conducted in cross-cultural linguistic contexts raise a number of issues. As a form of data collection, interviews provide researchers with insight into how individuals understand and narrate aspects of their lives. Challenges may arise, however, when language barriers exist between researchers and participants. In multilingual contexts, the study of language differences is an essential part of qualitative research. van Ness et al. claim that language differences may have consequences for the research process and outcome, because concepts in one language may be understood differently in another language.[23] For these authors, language is central in all phases of qualitative research, ranging from data collection to analysis and representation of the textual data in publications.

In addition, as[23]van Ness et al. observe, challenges of translation can be from the perspective that interpretation of meaning is the core of qualitative research. Interpretation and representation of meaning may be challenging in any communicative act; however, they are more complicated in cross-cultural contexts where interlingual translation is necessary.[23]). Interpretation and understanding of meanings are essential in qualitative research, not only for the interview phase, but also for the final phase when meaning will be represented to the audience through oral or written text.[19] Temple and Edwards claim that without a high level of translated understanding, qualitative research cannot shed light on different perspectives, circumstances that could shut out the voices of those who could enrich and challenge our understandings.[19]

Current state of affairs of cross-language studies in qualitative research

According to Temple et al.,[19] a growing number of researchers are conducting studies in English language societies with people who speak little or no English. However, few of these researchers acknowledge the influence of interpreters and translators. In addition, as Temple et al.[19] noticed, little attention is given to the involvement of interpreters in research interviews and even less attention to language difference in focus group research with people who do not speak English. An exception would be the work of Esposito.[24] There is some work on the role of interpreters and translators in relation to best practice and models of provision, such as that of Thomson et al.,[25] However, there is a body of literature aimed at English speaking health and social welfare professionals on how to work with interpreters.[26][27][28]

Temple and Edwards[19] point out the absence of technically focused literature on translation. This is problematic because there is strong evidence that communication across languages involves more than just a literal transfer of information[29][30][31][32]. In this regard, Simon claims that the translator is not someone who simply offers words in a one-to-one exchange.[30] Rather, the translator is someone who negotiates meanings in relation to a specific context. These meanings cannot be found within the language of translation, but they are embedded in the negotiation process, which is part of their continual reactivation[30]. For this reason, the translator needs to make continuous decisions about the cultural meanings language conveys. Thus, the process of meaning transfer has more to do with reconstructing the value of a term, rather than its cultural inscription.[30]

Significant contributions to cross-language studies in qualitative research

Jacques Derrida is widely acknowledged to be one of the most significant contributors to the issue of language in qualitative social research.[33][34][35][36][37][38] The challenges that arise in studies involving people who speak multiple languages have also been acknowledged.

Today, the main contributions concerning issues of translation and interpretation come from the nursing field. In a globalized era, setting the criteria for qualitative research that is linguistically and culturally representative of study participants is crucial for improving the quality of care provided by health care professionals.[24][39] Scholars in the health field, like Squires[40][16], provide useful guidelines for systematically evaluating the methodological issues in cross-language research in order to address language barriers between researchers and participants.

Cross-language concerns in qualitative research

Squires[16] defines cross-language as the process that occurs when a language barrier is present between the researcher and participants. This barrier is frequently mediated using a translator or interpreter. When the research involves two languages, interpretation issues might result in loss of meaning and thus loss of the validity of the qualitative study. As Oxley et al.[41]point out, in a multilingual setting interpretation challenges arise when researcher and participants speak the same non-English native language, but the results of the study are intended for an English-speaking audience. For instance, when interviews, observation, and other methods of gathering data are used in cross-cultural environments, the data collection and analysis processes become more complicated due to the inseparability of the human experience and the language spoken in a culture[41] Oxley et al. (2017). Therefore, it is crucial for researchers to be clear on what they know and believe. In other words, they should clarify their position in the research process.

In this context, positionality refers to the ethical and relational issues the researchers face when choosing a language over another to communicate their findings. For example, in his study on Chinese international students in a Canadian university, Li[42] considers the ethical and relational issues of language choice experienced when working with the Chinese and English language. In this case, it is important that the researcher offers a rationale behind his/her language choice. Thus, as Squires[40] observes, language plays a significant role in cross-cultural studies; it helps participants represent their sense of self.

Similarly, qualitative research interviews involve a continuous reflection on language choices because they may impact the research process and outcome. In his work, Lee[43] illustrates the central role that reflexivity plays in setting researcher’s priorities and his/her involvement in the translation process. Specifically, his study focuses on the dilemma that researchers speaking the same language of participants face when the findings are intended to an English-speaking audience only. Lee[43] introduces the article by arguing that “Research conducted by English-speaking researchers about other language speaking subjects is essentially cross-cultural and often multilingual, particularly with QR that involves participants communicating in languages other than English” (p.53[43]). Specifically, Lee addresses the problems that arise in making sense of interview responses in Mandarin, preparing transcriptions of interviews, and translating the Mandarin/Chinese data for an English-speaking/reading audience. Lee’s work then, demonstrates the importance of reflexivity in cross-language research since the researcher’s involvement in the language translation can impact the research process and outcome.

Therefore, in order to ensure trustworthiness, which is a measure of the rigor of the study, Lincoln & Guba[44], Sutsrino et al.[45] argue that it is necessary to minimize translation errors, provide detail accounts of the translation, involve more than one translator, and remain open to inquiry from those seeking access to the translation process. For example, in research conducted in the educational context, Sutsrino et al.[45] recommend bilingual researchers the use of inquiry audit for establishing trustworthiness. Specifically, investigators can require an outside person to review and examine the translation process and the data analysis in order to ensure that the translation is accurate, and the findings are consistent.

International educational organizations

The Society for Intercultural Education, Training and Research

SIETAR is an educational membership organization for those professionals who are concerned with the challenges and rewards of intercultural relations. SIETAR was founded in the United States in 1974 by a few dedicated individuals to draw together professionals engaged in various forms of intercultural learning and engagement research and training. SIETAR now has loosely connected chapters in numerous countries and a large international membership.

WYSE International

WYSE International is a worldwide educational charity specializing in education and development for emerging leaders established in 1989. It is a non-governmental organization associated with the Department of Public Information of the United Nations.

Over 3000 participants from 110 countries have attended their courses, they have run in 5 continents. Its flagship International Leadership Programme is a 12-day residential course for 30 people from on average 20 different countries (aged 18 – 35).

WYSE International's website states its aims are to:

"provide education independently of political, religious or social backgrounds and promote visionary leadership capable of responding to evolving world needs."[46]

Middle East Entrepreneurs of Tomorrow

Middle East Entrepreneurs of Tomorrow is an innovative educational initiative aimed at creating a common professional language between Israeli and Palestinian young leaders. Israeli and Palestinian students are selected through an application process and work in small bi-national teams to develop technology and business projects for local impact. Through this process of cross-cultural communication, students build mutual respect, cultural competence and understanding of each others.

Theories

The main theories for cross-cultural communication are based on the work done looking at value differences between different cultures, especially the works of Edward T. Hall, Richard D. Lewis, Geert Hofstede, and Fons Trompenaars. Clifford Geertz was also a contributor to this field. Also Jussi V. Koivisto's model on cultural crossing in internationally operating organizations elaborates from this base of research.

These theories have been applied to a variety of different communication theories and settings, including general business and management (Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner) and marketing (Marieke de Mooij, Stephan Dahl). There have also been several successful educational projects which concentrate on the practical applications of these theories in cross-cultural situations.

These theories have been criticized mainly by management scholars (e.g. Nigel Holden) for being based on the culture concept derived from 19th century cultural anthropology and emphasizing on culture-as-difference and culture-as-essence. Another criticism has been the uncritical way Hofstede’s dimensions are served up in textbooks as facts (Peter W. Cardon). There is a move to focus on 'cross-cultural interdependence' instead of the traditional views of comparative differences and similarities between cultures. Cross-cultural management is increasingly seen as a form of knowledge management. While there is debate in academia, over what cross-cultural teams can do in practice, a meta-analysis by Günter Stahl, Martha Maznevski, Andreas Voigt and Karsten Jonsen on research done on multicultural groups, concluded "Research suggests that cultural diversity leads to process losses through task conflict and decreased social integration, but to process gains through increased creativity and satisfaction."[47]

Aspects

There are several parameters that may be perceived differently by people of different cultures:

- High- and low-context cultures: context is the most important cultural dimension and also difficult to define. The idea of context in culture was advanced by the anthropologist Edward T Hall. He divides culture into two main groups: High and Low context cultures. He refers to context as the stimuli, environment or ambiance surrounding the environment. Depending on how a culture relies on the three points to communicate their meaning, will place them in either high or low- context cultures. For example, Hall goes on to explain that low-context cultures assume that the individuals know very little about what they are being told, and therefore must be given a lot of background information. High-context cultures assume the individual is knowledgeable about the subject and has to be given very little background information.

- Nonverbal, oral and written: the main goal behind improving intercultural audiences is to pay special attention to specific areas of communication to enhance the effectiveness of the intercultural messages. The specific areas are broken down into three sub categories: nonverbal, oral and written messages.

Nonverbal contact involves everything from something as obvious as eye contact and facial expressions to more discreet forms of expression such as the use of space. Experts have labeled the term kinesics to mean communicating through body movement. Huseman, author of Business Communication, explains that the two most prominent ways of communication through kinesics are eye contact and facial expressions.

Eye contact, Huseman goes on to explain, is the key factor in setting the tone between two individuals and greatly differs in meaning between cultures. In the Americas and Western Europe, eye contact is interpreted the same way, conveying interest and honesty. People who avoid eye contact when speaking are viewed in a negative light, withholding information and lacking in general confidence. However, in the Middle East, Africa, and especially Asia, eye contact is seen as disrespectful and even challenging of one's authority. People who make eye contact, but only briefly, are seen as respectful and courteous.

Facial expressions are their own language by comparison and universal throughout all cultures. Dale Leathers, for example, states that facial expression can communicate ten basic classes of meaning.

The final part to nonverbal communication lies in our gestures, and can be broken down into five subcategories:

- Emblems

Emblems refer to sign language (such as, thumbs up, one of the most recognized symbols in the world)

- Illustrators

Illustrators mimic what is spoken (such as gesturing how much time is left by holding up a certain number of fingers).

- Regulators

Regulators act as a way of conveying meaning through gestures (raising up a hand for instance indicates that one has a certain question about what was just said) and become more complicated since the same regulator can have different meanings across different cultures (making a circle with a hand, for instance, in the Americas means agreement, in Japan is symbolic for money, and in France conveys the notion of worthlessness).

- Affect displays

Affect displays reveal emotions such as happiness (through a smile) or sadness (mouth trembling, tears).

- Adaptors

Adaptors are more subtle such as a yawn or clenching fists in anger.

The last nonverbal type of communication deals with communication through the space around people, or proxemics. Huseman goes on to explain that Hall identifies three types of space:

- Feature-fixed space: deals with how cultures arrange their space on a large scale, such as buildings and parks.

- Semifixed feature space: deals with how space is arranged inside buildings, such as the placement of desks, chairs and plants.

- Informal space: the space and its importance, such as talking distance, how close people sit to one another and office space are all examples. A production line worker often has to make an appointment to see a supervisor, but the supervisor is free to visit the production line workers at will.

Oral and written communication is generally easier to learn, adapt and deal with in the business world for the simple fact that each language is unique. The one difficulty that comes into play is paralanguage, how something is said.

Differences between Western and Indigenous Australian communication

According to Michael Walsh and Ghil'ad Zuckermann, Western conversational interaction is typically "dyadic", between two particular people, where eye contact is important and the speaker controls the interaction; and "contained" in a relatively short, defined time frame. However, traditional Australian Aboriginal conversational interaction is "communal", broadcast to many people, eye contact is not important, the listener controls the interaction; and "continuous", spread over a longer, indefinite time frame.[48][49]

See also

- The Contact Zone (theoretical concept)

- Cross-cultural

- Cross-cultural studies

- Cultural bias

- Cultural competence

- Cultural dimensions

- Cultural diversity

- IATIS

- Intercultural communication principles

- Intercultural competence

- Intercultural relations

- Interculturality

- Translation

- Intercultural communication

- Human communication

Footnotes

- "Japan Intercultural Consulting". Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Everett M. Rogers, William B. Hart, & Yoshitaka Miike (2002). Edward T. Hall and The History of Intercultural Communication: The United States and Japan. Keio Communication Review No. 24, 1-5. Accessible at http://www.mediacom.keio.ac.jp/publication/pdf2002/review24/2.pdf.

- Bartell, M. (2003). Internationalization of universities: A university culture-based framework. Higher Education, 45(1), 44, 48, 49.

- Hans Köchler (ed.), Cultural Self-comprehension of Nations. Tübingen: Erdmann, 1978, ISBN 978-3-7711-0311-8, Final Resolution, p. 142.

- Deardorff, Darla K. (2015). "A 21st Century Imperative: Integrating intercultural competence in Tuning". Tuning Journal for Higher Education. 3: 137. doi:10.18543/tjhe-3(1)-2015pp137-147.

- Bartell, M. (2003). Internationalization of universities: A university culture-based framework. Higher Education, 45(1), 46.

- Rymes, (2008). Language Socialization and the Linguistic Anthropology of Education. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2(8, Springer)

- "Fact and Figure about cross cultural training". Cultural Candor Inc. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Teather, D. (2004). The networking alliance: A mechanism for the internationalisation of higher education? Managing Education Matters, 7(2), 3.

- Rudzki, R. E. J. (1995). The application of a strategic management model to the internationalization of higher education institutions. Higher Education, 29(4), 421-422.

- Cameron, K.S. (1984). Organizational adaptation and higher education. Journal of Higher Education 55(2), 123.

- Ellingboe, B.J. (1998). Divisional strategies to internationalize a campus portrait: Results, resistance, and recommendations from a case study at a U.S. university, in Mestenhauser, J.A. and Ellingboe, B.J (eds.), Reforming the Higher Education Curriculum: Internationalizing the Campus. Phoenix, AZ: American Council on Education and Oryx Press, 199.

- Bartell, M. (2003). Internationalization of universities: A university culture-based framework. Higher Education, 45(1), 48.

- Van Hook, S.R. (2011, 11 April). Modes and models for transcending cultural differences in international classrooms. Journal of Research in International Education, 10(1), 5-27. http://jri.sagepub.com/content/10/1/5

- "Cross Cultural Management". Ivey Business School. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Squires, Allison (February 2009). "Methodological challenges in cross-language qualitative research: A research review". International Journal of Nursing Studies. 46 (2): 277–287. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.006. PMC 2784094. PMID 18789799.

- Edwards, Rosalind (January 1998). "A critical examination of the use of interpreters in the qualitative research process". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 24 (1): 197–208. doi:10.1080/1369183x.1998.9976626. ISSN 1369-183X.

- Mill, Judy E.; Ogilvie, Linda D. (January 2003). "Establishing methodological rigour in international qualitative nursing research: a case study from Ghana". Journal of Advanced Nursing. 41 (1): 80–87. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02509.x. ISSN 0309-2402. PMID 12519291.

- Temple, Bogusia; Edwards, Rosalind (June 2002). "Interpreters/Translators and Cross-Language Research: Reflexivity and Border Crossings". International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 1 (2): 1–12. doi:10.1177/160940690200100201. ISSN 1609-4069.

- Tinsley, Royal L.; Bassnet-McGuire, Susan (1982). "Translation Studies". The Modern Language Journal. 66 (1): 77. doi:10.2307/327826. ISSN 0026-7902. JSTOR 327826.

- Saville-Troike, M. (1989). The ethnography of communication: An introduction (2nd ed.). New York: Basil Blackweli.

- Stanton, A. (1996). Reconfiguring teaching and knowing in the college classroom. In Goldberger, N.R., Tarule,J.M., Clinchy, B.M., & Beienky, M.F. (Eds). Knowledge, difference, and power (pp, 25-56). Basic Books

- Van Nes, Fenna; Abma, Tineke; Jonsson, Hans; Deeg, Dorly (2010). "Language differences in qualitative research: Is meaning lost in translation?". European Journal of Ageing. 7 (4): 313–316. doi:10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y. PMID 21212820.

- Esposito, Noreen (2001). "From Meaning to Meaning: The Influence of Translation Techniques on Non-English Focus Group Research". Qualitative Health Research. 11 (4): 568–579. doi:10.1177/104973201129119217. PMID 11521612.

- Thomson, A.M., Rogers, A., Honey, S., & King, L. (1999). If the interpreter doesn’t come there is no communication: A study of bilingual support services in the North West of England. Manchester: School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting, University of Manchester.

- Freed, A. O. (1988, July/August). Interviewing through an interpreter. Social Work, 315-319.

- Fuller, J. H. S. & Toon, P. D. (1988). Medical practice in a multicultural society. Heinemann Medical.

- Karseras, P., & Hopkins, E. (1987). British Asians’ health in the community. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

- Simon, S. (1996). Gender in translation: Cultural identity and the politics of transmission. Routledge.

- Spivak, G. C. (1992). The politics of translation. In M. Barrett & A. Phillips (Eds.), Destabilising theory: Contemporary feminist debates (pp. 177-200). Polity Press

- Temple, B. (1997). Issues in translation and cross-cultural research. Sociology, 31 (3), 607-618.

- Derrida, J. (1967a). Marges de la philosophie [Margins of philosophy]. Galilée.

- Derrida, J. (1967b). Écriture et différence [Writing and difference]. Éditions du Seuil.

- Derrida, J. (1996). Le monolinguisme de l'autre ou la prothèse de l'origine [Monolingualism of the other or The prosthesis of origin]. Galilée.

- Derrida, J. (1998a). Monolingualism of the other or The prosthesis of origin. Stanford University Press.

- Derrida, J. (1998b). The secret art of Antonin Artaud. MIT Press.

- Temple B. (2002). Crossed wires: Interpreters, translators, and bilingual workers in cross-language research. Qualitative Health Research, 12 (6), 844–54.

- Yach D. (1992). The use and value of qualitative methods in health research in developing countries. Social Science & Medicine, 35 (4), 603–612.

- Squires, A. (2008). "Language barriers and qualitative nursing research: Methodological considerations". International Nursing Review. 55 (3): 265–273. doi:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00652.x. PMC 2697452. PMID 19522941.

- Oxley, Judith; Günhan, Evra; Kaniamattam, Monica; Damico, Jack (2017). "Multilingual issues in qualitative research". Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 31 (7–9): 612–630. doi:10.1080/02699206.2017.1302512. PMID 28665758.

- Li, Y. (2011). Translating Interviews, Translating Lives: Ethical Considerations in Cross-Language Narrative Inquiry. TESL Canada Journal, 28(5), 16–30.

- Lee, S. (2017). The Bilingual Researcher’s Dilemmas: Reflective Approaches to Translation Issues. Waikato Journal of Education, 22(2), 53–62.

- Lincoln, Y., Guba, E., 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage.

- Sutrisno, A., Nguyen, N. T., & Tangen, D. (2014). Incorporating Translation in Qualitative Studies: Two Case Studies in Education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (QSE), 27(10), 1337–1353.

- "WYSE International". WYSE International. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Stahl, Günter; Maznevski, Martha; Voigt, Andreas; Jonsen, Karsten (May 2010). "Unraveling the Effects of Cultural Diversity in Teams: A Meta-Analysis of Research on Multicultural Work Groups". Journal of International Business Studies. 41 (4): 690–709. doi:10.1057/jibs.2009.85. JSTOR 40604760.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad; et al. (2015), ENGAGING - A Guide to Interacting Respectfully and Reciprocally with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, and their Arts Practices and Intellectual Property (PDF), Australian Government: Indigenous Culture Support, p. 12, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2016

- Walsh, Michael (1997), Cross cultural communication problems in Aboriginal Australia, Australian National University, North Australia Research Unit, pp. 7–9

- Mary Ellen Guffey, Kathy Rhodes, Patricia Rogin. "Communicating Across Cultures." Mary Ellen Guffey, Kathy Rhodes, Patricia Rogin. Business Communication Process and Production. Nelson Education Ltd., 2010. 68-89.

References

- Bartell, M. (2003). Internationalization of universities: A university culture-based framework. Higher Education, 45(1), 44, 46, 48, 49.

- Cameron, K.S. (1984). Organizational adaptation and higher education. Journal of Higher Education 55(2), 123.

- Ellingboe, B.J. (1998). Divisional strategies to internationalize a campus portrait: Results, resistance, and recommendations from a case study at a U.S. university, in Mestenhauser, J.A. and Elllingboe, B.J (eds.), Reforming the Higher Education Curriculum: Internationalizing the Campus. Phoenix, AZ: American Council on Education and Oryx Press, 199.

- Everett M. Rogers, William B. Hart, & Yoshitaka Miike (2002). Edward T. Hall and The History of Intercultural Communication: The United States and Japan. Keio Communication Review No. 24, 1-5.

- Hans Köchler (ed.), Cultural Self-comprehension of Nations. Tübingen: Erdmann, 1978, ISBN 978-3-7711-0311-8, Final Resolution, p. 142.

- Rudzki, R. E. J. (1995). The application of a strategic management model to the internationalization of higher education institutions. Higher Education, 29(4), 421-422.

- Rymes, (2008). Language Socialization and the Linguistic Anthropology of Education. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2(8, Springer), 1.

- Teather, D. (2004). The networking alliance: A mechanism for the internationalisation of higher education? Managing Education Matters, 7(2), 3.

- Van Hook, Steven R. (2011). "Modes and models for transcending cultural differences in international classrooms". Journal of Research in International Education. 10: 5–27. doi:10.1177/1475240910395788.

- Deardorff, Darla K. (2015). "A 21st Century Imperative: Integrating intercultural competence in Tuning". Tuning Journal for Higher Education. 3: 137. doi:10.18543/tjhe-3(1)-2015pp137-147.

External links

- "Voices on Antisemitism," Interview with Diego Portillo Mazal, from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Communicating Across Cultures

- Inter cultural Research: The Current State of Knowledge

- A Dozen Rules of Thumb for Avoiding Inter cultural Misunderstandings

- Inter cultural Teachers Training Project INNOCENT: teachers learn cross-cultural communication by doing a free Web Based Training WBT

- International Association for Intercultural Communication Studies (IAICS)

- International Association for Translation and Intercultural Studies (IATIS)