Coronation of Bokassa I

The Coronation of Bokassa I as the Emperor of Central Africa took place on 4 December 1977 at a sports stadium in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Empire. It was the only coronation in the history of the Empire—a short-lived one-party state and self-proclaimed monarchy—which was established in 1976 by Jean-Bédel Bokassa, military dictator and president for life of the Central African Republic.

The coronation—which was almost an exact copy of the coronation of Napoleon I as Emperor of the French in 1804—and related events were marked by luxury and pomp. Despite substantial material support from France,[1] expenses amounted to over US$20 million ($80 million today) and caused serious damage to the state, leading to a huge outcry in Africa and around the world. After the coronation, Bokassa stayed in power for less than two years. In September 1979, Operation Caban took place in his absence, as a result, the country became a republic again.[2][3]

Background

Part of a series on the |

|---|

|

|

|

Early history

|

|

Colonial period

|

|

Independence

|

|

Current period

|

|

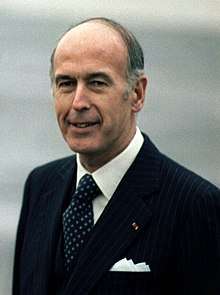

In the spring of 1976, during a visit by the French president, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, Bokassa told him about his plans to proclaim the Central African Republic an empire and celebrate the occasion.

According to Bokassa, the creation of a monarchy would help Central Africa improve its standing vis-à-vis the rest of the continent and increase its authority in the international arena.[4]. The French leader proposed to hold a modest coronation ceremony in the traditional African style, avoiding high costs because the Central African Republic was one of the poorest countries in Africa, and an opulent ceremony could have negative economic and social consequences.[3]

Bokassa persistently requested d'Estaing for France's assistance in organizing the event. The French President was forced to agree for several reasons: first, the refusal could jeopardize the continuation of the profitable French role in the mining industry of the Central African Republic—mostly of uranium and diamonds[5]—and secondly, France was interested in maintaining its influence in the country, which, along with Gabon and Zaire, was part of the triangle on which French policy in the region rested. Anxiety on the part of France was heightened after Bokassa attempted to draw closer to Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, who had strained relations with France and pro–French Chad (because of a territorial dispute).[4] This forced d'Estaing to promise material assistance to the Central African President in exchange for cutting ties with Gaddafi.[1]

On 4 December 1976, at the extraordinary congress of the ruling MESAN party, Bokassa announced the renaming of the Central African Republic to the Central African Empire and proclaimed himself Emperor. At the congress, a pre-prepared constitution of the empire was adopted, according to which the Emperor was the head of the executive power, and the monarchy was declared to be hereditary, transferred down a male line in the event that the Emperor himself did not appoint a future successor. His full title was "Emperor of Central Africa by the will of the Central African people, united within the national political party, the MESAN." Shortly after the proclamation of the empire, Bokassa, who had adopted Islam and changed his name to Salah Eddine Ahmed Bokassa during a September 1976 visit by Gaddafi, converted back to Catholicism.[6]

The first world leader to congratulate Bokassa on the imperial title was d'Estaing, who for several years maintained friendly relations with Bokassa. In 1975, the French head of state called himself a friend and family member of the Central African President.[7] In addition, d'Estaing visited the Central African Republic several times to hunt on the private estates of Bokassa, from where he and his brothers brought elephant tusks, mounted heads of lions and diamonds presented to them by Bokassa himself, which became clear somewhat later. The future dictator of the Central African Republic was well acquainted with the first President of the French Fifth Republic, Charles de Gaulle, who considered him to be his ally in arms. After the death of de Gaulle, Bokassa himself said: "I lost my biological father as a child, and now I turned towards my true father, General de Gaulle ..."[8]

Preparations

Bokassa planned to conduct his coronation on 4 December 1977, exactly one year after the proclamation of the Central African Empire, following the example of Napoleon who was crowned on 2 December 1804, in Notre-Dame de Paris. He considered the Emperor of the French as his idol.[5]. Beside Bokassa himself, his "spouse number one" Catherine Denguiadé was to be crowned during the ceremony.[9] Their son, Jean-Bédel Bokassa Jr., one of more than 40 children of Bokassa, was proclaimed the Crown Prince and heir apparent to the imperial throne. Consequently, he continues to be the head of the House of Bokassa and the formal pretender to the imperial throne to the present day.[10] Other close relatives of the Emperor received titles of princes and princesses.

In preparation for the coronation, several special committees were formed, each of them responsible for a specific area of preparation. Thus, the committee responsible for the accommodation was charged with finding suitable premises for 2,500 foreign guests. To this end, having received permission from Bokassa, the committee members began to requisition apartments, houses, and hotels from the inhabitants of Bangui for the period of the celebrations, and repaired the rooms intended for guests. The task of another committee was to completely change the appearance of the capital, and especially those areas that were to be used during the coronation. Under its leadership, street cleaning, painting of buildings, as well as removal of urban beggars and vagrants outside the central areas of Bangui took place.[11]

Textile enterprises of the Central African Empire were engaged in sewing hundreds of ceremonial costumes for local residents, who were to become guests at the ceremony. The authorities regulated a certain dress code: children were instructed to wear white clothing, middle-level officials dark blue, and high-ranking officials and ministers black.[11]

While preparations were being made in the capital for the event, Bokassa sought contacts with foreign artists and invited them to Bangui to perpetuate his name in their works. West German artist Hans Linus Murnau painted two large portraits of the Emperor. In one, Bokassa was depicted bareheaded, and in the other, wearing a crown. The last portrait was subsequently used in a commemorative postage stamp dedicated to the coronation.[11] In addition, the Imperial March and the Imperial Waltz were written in France, as well as the coronation ode, which consisted of 20 quatrains.[11]

Many of the objects used in the coronation were made by French masters. As early as November 1976, the representative of the Central African Embassy in France confidentially informed the sculptor Olivier Brice that President Bokassa would like to involve him in the work on the decoration of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame in Bangui. In addition, Brice was instructed to develop projects of the Imperial Throne and carriage.[12]

Bokassa ordered a large diamond ring from American entrepreneur and political operative Albert Jolis who took the order but did not have the funds to purchase a fairly large stone. Jolis arranged to process a low-grade, finely crystalline, black diamond, resembling the outlines of Africa on the map, and inserted it into a large ring. The place on the black diamond which roughly corresponded to the position of the Central African Empire in Africa, was decorated with a colorless diamond. The item, whose value did not exceed US$500, was presented to Bokassa as a unique diamond worth more than US$500,000.[13] After his overthrow, Bokassa took "a unique diamond" with him into exile, and Jolis cynically did not recommend selling it.[14]

The Imperial Throne, made of gilded bronze, was designed as a sitting eagle with outstretched wings. The height of the throne was three and a half by four and a half meters (11 by 15 ft), and weighed about two tons.[15] For the manufacture of the throne, Brice built a special workshop near his home in Gisors in Normandy, where about 300 workers were employed. The throne seat of red velvet, which occupied the cavity in the belly of the gilded eagle, was made by local draper Michel Cousin. In total, the cost of the throne was approximately US$2,500,000. For the carriage, in which Bokassa was to pass through the streets of Bangui on the day of the coronation, the sculptor Brice bought an old carriage in Nice, restored it, covered it with velvet on the inside, and partially decorated it with gold and added emblems to the outside. Eight white horses, which were planned to be harnessed to the Emperor's carriage, were procured from Belgium. In addition, several dozen of Norman gray horses were acquired for the Emperor's escort, whose members spent the entire summer of 1977 in Norman Lisieux, where they passed special riding courses.[12]

Most of the costumes were also made in France. The French company, Guiselin, which once performed similar work under Napoleon, took up the creation of a coronation suit for the Emperor, in association with Pierre Cardin. The imperial attire consisted of a long, to-the-floor, toga, decorated with thousands of tiny pearls; shoes decorated with pearls, as well as a nine-meter (30 ft) mantle of crimson velvet, decorated with golden emblems in the form of eagles and edged with ermine fur. All this together cost the Central African treasury US$145,000. Another US$72,400 was the cost of a dress made by Lanvin for Empress Catherine and adorned with 935 thousand metallic glitters. In addition to the dress, a mantle was made for the Empress, similar to the Emperor's mantle, but in a more modest size.[12]

The Imperial Crown was made by Arthus Bertrand, a jeweler from Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The design of the crown was traditional: it had a heavy frame resting on an ermine headband with a crimson canopy. A golden crown was placed over the headband, in the middle of which was placed the figure of an eagle, and eight arcs branched from the crown, supporting the blue sphere—the symbol of the Earth—on which the outlines of Africa were highlighted in golden color. In addition, the entire crown was inlaid with diamonds, the largest of which—80 carats—was in the center of the figure of an eagle, in the most prominent place.[15] The cost of the crown is estimated at no less than US$2,500,000. A separate crown, in the form of a wreath, adorned with a 25-carat diamond, was also intended for the Empress. In addition, the imperial sceptre, sword, and several items of jewelry were made for the coronation. All this, including both crowns, was estimated at about US$5,000,000.[16]

More than 240 tons of food and beverages that were supposed to be served at the banquet after the coronation were also delivered to the country by airplanes from Europe. One winery in Bangui delivered up to 40,000 bottles, including the production of farms Château Lafite Rothschild and Château Mouton Rothschild, harvest 1971. Each bottle at that time was estimated at about US$25. In addition to wine, Bokassa ordered 24,000 bottles of Moët & Chandon champagne and his favorite Scotch whisky, Chivas Regal, as well as 10,000 items of silverware.[1]

Finally, in order for foreign guests to be adequately received in Bangui, Bokassa ordered the purchase of 60 new Mercedes-Benz cars. Since the country was landlocked, the vehicles were initially transported to a port in Cameroon and then flown to Bangui at a cost of US$300,000.[1]

When everything designed for the coronation ceremony was successfully purchased and delivered to Bangui, the total amount, including both foreign acquisitions and domestic costs, was about US$22,000,000. For the economy of a backward, practically impoverished African state such as the Central African Empire, this amount was extremely high, and equal to a quarter of the country's annual budget. Most of the expenses were paid by France, in exchange for the promised break with Libya. "Everything here was financed by the French government. We ask the French for money, get it and waste it."[17] Still, the Central African Empire had to pay a significant amount.[1]

Invitations

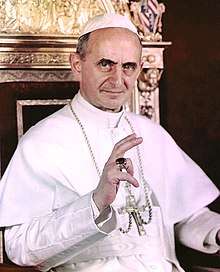

As conceived by Bokassa, his coronation was to take place with the obligatory presence of Pope Paul VI. Apparently he intended, as supposedly Napoleon had done with Pope Pius VII at his coronation, to take the crown from the hands of the Paul VI and place it on his head himself. With a request to invite the head of the Catholic Church to the coronation, Bokassa turned to the Archbishop of Bangui, Monsignor Joachim N'Dayen, and Apostolic Nuncio in the Central African Empire, Oriano Quilici.

Resisting this idea, Quilici explained to Bokassa in June 1977 that the Pope was too old for such a long journey and would not be able to attend the ceremony. The best that Quilici could offer Bokassa was to hold the Mass after the coronation ceremony. Upon receiving the consent of Bokassa, Quilici contacted the Vatican City and secured an agreement for the Pope to be represented by Archbishop Domenico Enrici, who had recently represented the Pope during the enthronement of King Juan Carlos I of Spain in 1975.[18]

The greatest concern on the part of Bokassa was caused by the refusals of the heads of state, including the monarchs invited to Bangui. Invitations were rejected by both Emperor Hirohito of Japan and Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran – the first in the guest list compiled by Bokassa. The other ruling monarchs, one by one, also did not express a desire to attend the ceremony. The Prime Minister of Mauritius, Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, and the president of Mauritania, Moktar Ould Daddah, responded to the invitation by sending their spouses to Bangui. Prince Emmanuel of Liechtenstein was the only royal who flew to Bangui.

Most of the states at the coronation ceremony were represented by their ambassadors, and a number of countries boycotted the ceremony altogether. Authoritarian African leaders such as Omar Bongo of Gabon, Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, and Idi Amin of Uganda found reasons to refuse to visit the Central African Empire. Later, in one of his interviews, Bokassa motivated their refusals by saying: "They were jealous of me because I had an empire and they didn’t."[19]

Most unexpected was the decision of the French President not to attend. He limited himself to sending a sword of the Napoleonic era to Bokassa as a gift on behalf of the French government. The French head of state was represented in Bangui by the Minister of Cooperation Robert Galley and presidential adviser on African affairs René Journiquek. Supporting Bokassa, Galley condemned high-ranking officials who refused to accept an invitation to Bangui, but who were willing to take part in the Silver Jubilee of Elizabeth II. "It smacks of racism," he concluded. In the end, of the 2,500 invited guests, only 600 agreed to come, including 100 journalists. Despite the complete absence of heads of state, there was no shortage of diplomats and businessmen in Bangui, including European ones.[19]

Ceremony

On 4 December 1977, at 07:00 West Africa Time, Mercedes-Benz limousines were already carrying guests in the direction of the new Yugoslav-built basketball stadium, where the coronation was to take place. On the way to the stadium, cars drove through the newly repaired streets of Bangui, and passed by the Jean-Bédel Bokassa Sports Palace, along Bokassa Avenue, not far from the Jean-Bédel Bokassa University.[18] By 08:30, all the guests and participants of the ceremony—about 4,000 people—were in their seats, and by 09:00, the arrival of Bokassa himself was expected. To maintain the appropriate atmosphere, the speakers located in the stadium loudly played solemn music.[19]

The part of the stadium where the coronation was supposed to take place was, according to Brice's plan, decorated with banners and tapestries of national colors, and red curtains and carpeting. The low platforms seating the thrones of the Emperor and Empress were completely red. The Empress' throne was much more modest than the Emperor's: it was a high chair made of red velvet with a gold-fringed, velvet canopy. To his left was a small seat for the Crown Prince.[19] The stadium was carefully guarded by the French troops, sent "to secure the ceremony."[20]

By 09:00, the motorcade of Bokassa was still on the way, and the famous French Navy orchestra of 120 people,[20] present at the stadium, began to play an old drinking song, Chevaliers de la table ronde, to distract guests. Since the air conditioning at the stadium did not work, the extremely high temperature—more than 35 °C (95 °F)—gradually made itself felt, which created discomfort for those present who were dressed in suits and evening dresses. Some, in order not to sweat, fanned the ceremony programs, which were given out to each guest. Only at about 10:10, the imperial motorcade, which had traveled several kilometers in length from the Renaissance Palace itself, arrived at the stadium. Along the motorcade route, a change occurred: unable to withstand the heat of riding in a closed carriage, Bokassa and Empress Catherine moved into one of the Mercedes equipped with air conditioning, and several hundred meters before reaching the end point of the route they moved back to the carriage again.[19]

At 10:15, the coronation ceremony began. The first to enter the hall were two guardsmen in military uniforms of the Napoleonic era who carried the national flag and the imperial standard to the end of the carpet. They then stood with the flags on either side of the platform where the thrones were located. After the guardsmen followed the Crown Prince. The boy was dressed in a white, military-parade uniform with a golden braid and a ribbon over his shoulder, and a white cap on his head. Next, Empress Catherine appeared in the hall. A mantle was fastened on top of her dress, and a golden, laurel-like wreath adorned her head. The Empress was accompanied by ladies-in-waiting in pink and white evening dresses and wide-brimmed hats, who supported the long train of her dress until she reached her throne.[21]

Before Bokassa himself entered the hall, the naval orchestra went silent. A voice from the loudspeaker announced to drumming: "His Imperial Majesty Bokassa I, the Emperor of Central Africa!" Accompanied by the sounds of an imperial march, the Emperor appeared on the carpet, dressed in a white toga with a belt having five stripes of the colors of the national flag. A wide ribbon was draped over Bokassa's shoulder, white antelope skin gloves covered his hands, and his head was decorated with a golden wreath, crafted in ancient Roman style. Accompanied by his escort, cameramen and photographers, he climbed onto the platform to his throne, after which the guardsmen handed him attributes of imperial power: a sword and a two-meter (6.6 ft) sceptre, which Bokassa took in his right hand. Then several pairs of guardsmen brought a long velvet mantle to the throne, and one of them put it on the Emperor. After this, Bokassa himself placed the crown on his head. The audience responded with applause. To complete it the ceremony, the Emperor publicly took the oath to the Central African people:[22]

We, Bokassa I, the Emperor of Central Africa, by the will of the Central African people ... solemnly swear and promise – before the people, before all mankind and before history – to do everything possible to protect the Constitution, protect national independence and territorial integrity ... and serve the Central African people in accordance with the sacred ideals of the national political party.

When Bokassa finished speaking, the audience applauded again, and loudspeakers sounded La Renaissance, the national anthem, in the Sango language. Upon its completion, the coronation of Empress Catherine began. Dressed in a robe, she went to her husband and knelt in front of him, after which he took off the wreath from her head and placed the crown. This scene, as witnesses of the coronation noticed, had a noticeable similarity to the moment captured on the painting The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David.[5] Noticeably, the French minister Robert Galley was dressed during the coronation as Marshal of the Empire Michel Ney during the coronation of Napoleon.[23] The coronation ceremony was completed with a performance of the choir who arrived at the stadium.[24]

After the coronation, the Emperor, the Empress with ladies-in-waiting, the Crown Prince, and the rest of the children of Bokassa, went to the Mass at the Cathédrale Notre-Dame, two kilometers from the stadium. Along the way, they were accompanied by an equestrian unit of hussars. While the Emperor and the Empress rode again in a closed carriage, the Crown Prince was separated from them, in an open horse-drawn carriage. On the way to the Cathédrale, the imperial cortege passed under the triumphal arches and banners with the letter "B", which appeared in Bangui on the eve of the festivities. Along the road crowds stood on the sidewalks, however, their actions, according to Brian Titley, did not demonstrate "obvious enthusiasm."[24]

In the Cathédrale, two thrones were prepared in advance for the Emperor and the Empress, and a small seat for the Crown Prince, similar to the one in the stadium. A few more seats were intended for high-ranking guests, but they didn't have enough seats for all, and many had to remain standing. The Mass in three languages—French, Latin, and Sango—was held by Archbishop N'Dayen. He preached with dignity, wishing the Emperor success, but avoiding the expected excessive praise and adulation.[24]

The new Roman Pontifical promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1970 as part of the liturgical reforms that followed the Second Vatican Council did not contain (and, to this day, its revised editions do not contain) a Coronation Rite. Accordingly, at present, the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church only possesses a Coronation Rite in its Tridentine extraordinary form (the universal use of which was permitted by Pope Benedict XVI in 2007). However, the postconciliar ordinary form of the Roman Rite has never included a ritual for the Coronation of monarchs, and none was created in 1977 for the Coronation of the Central African Emperor, even on an ad hoc basis. Accordingly, the part of Bokassa's Coronation ceremony held at the stadium, prior to the Mass that followed at the Cathédrale, was not a religious ceremony but a secular affair, including the moment of his actual crowning. As for the Solemn Mass that followed at the cathedral, that religious part of the festivities did not consist of any special Coronation ritual, but was a regular Mass of Thanksgiving, following the normal rubrics for a solemn Mass celebrated by a Bishop. Because there was no actual Coronation liturgy, Bokassa was not anointed at any point during the celebrations.

Dinner

The last event of 4 December was an evening banquet at the Renaissance Palace hosted by Bokassa for, in his view, the most outstanding guests. Those who were not invited to the reception, went to the bar of the Hotel Rock, equipped with air conditioning.[25]

A total of about 400 people attended the banquet. Since, by evening, the heat in the capital had gradually subsided, the event was held in the open air: the tables where guests were seated were located in a vast, picturesque garden, decorated with fountains and bone carvings, adjacent to the Palace. For security, the garden was protected by bulletproof glass screens.[26] By 21:00, when all the guests had gathered, the waiters started serving food, although Bokassa, as usual, was late and only appeared after some time. By this time, he changed his coronation clothes and regalia for a marshal's uniform with a cap featuring a cockade and ostrich feathers, and a black diamond ring glittered on the Emperor's finger. The Empress who accompanied him wore a long, haute couture, French evening dress.[25]

A variety of dishes were served at the banquet. For dessert, the guests were offered a huge seven-layer imperial cake, decorated with green icing. When the cake was taken to the tables, the top part was removed from it, releasing half a dozen pigeons outside. Dishes on the tables corresponded to its contents: dinner was served on gold and porcelain plates, ordered specially from the famous Limoges master Berardo.[27] When the guests had eaten enough, Bokassa leaned over to Robert Galley and whispered: "You did not notice it, but you ate human meat." It is not known whether the Emperor was telling the truth or not, but later his words became one of the reasons for the belief that Bokassa was a cannibal.[25] Moreover, it is believed that the served meat belonged to prisoners held in a Bangui prison.[26]

After dinner, a scheduled 35-minute break took place, during which a festive firework display was given at the Palace. Pyrotechnics, were brought from Paris.[28] The fireworks were followed by a pop show in which several songs were performed by a song-and-dance group of former bar girls from Saigon, South Vietnam. The French naval orchestra, which had performed at the stadium, also participated. When it played the "Imperial Waltz," written in France specifically on the occasion of the coronation of Bokassa, the Emperor and Empress invited guests to the dance floor. The party came to an end around 02:30.[25]

Parade

On the morning of 5 December 1977, a solemn parade began in Bangui to mark the coronation of Bokassa. The parade was held on one of the main avenues of the Central African capital, where a special review platform was installed for the Emperor and his guests. At 10:00, Bokassa arrived, again an hour late. The Emperor was again dressed in a marshal's uniform, and Catherine was dressed in a garden party dress and a pale, purple, wide-brimmed hat.[29]

The parade was the final part of the celebrations accompanying the coronation. Additionally, in the afternoon, a number of sporting events were held in Bangui, also timed to coincide with the coronation, the largest of which was the Coronation Cup basketball tournament—the Emperor himself was present. Later that evening, several parties and receptions took place. Gradually, the festive atmosphere in the capital faded and the guests began to go home, after which Bangui returned to the usual way of life.[30]

Assessment

The coronation of Bokassa I provoked a mixed reaction throughout the world, and led to mainly negative comments in Africa. Kenya's Daily Nation referred to Bokassa's "clowning glory," while the Zambia Daily Mail deplored his "obnoxious excesses." The reaction in Europe was generally dismissive: French journalists associated the coronation with a masquerade, ridiculing the wastefulness and vanity of Bokassa. The assessment of French president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing was more optimistic. Having watched the recording of the ceremony on TV, he called what was happening “beautiful” and emphasized the “certain dignity” of such a coronation. He compared Empress Catherine with Napoleon's wife, Empress Joséphine, calling them both "incarnations of modesty and charm."[30]

Despite the fact that the coronation and accompanying celebrations caused serious damage to the state budget, Bokassa was not the only contemporary monarch who decided to stage a similar lavish event: in 1971, on the occasion of the 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of the Imperial State of Iran declared himself the successor to Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire, and spent about US$100 million ($630 million today) to celebrate the anniversary. This amount far exceeded the one that was spent by Bokassa in 1977.[30]

References

Footnotes

- Titley 2002, p. 91.

- Titley 2002, p. 98.

- Колкер 1982, p. 143.

- Колкер 1982, p. 142.

- Titley 2002, p. 83.

- Musky 2002, pp. 77–78.

- K. Martial Frindéthié, Martial Kokroa Frindéthié (2010). Globalization and the seduction of Africa's ruling class: an argument for a new philosophy of development. McFarland. p. 64.

- Taylor, Ian. (2010). The international relations of Sub-Saharan Africa. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 55.

- Crabb, John H. (1978). "The Coronation of Emperor Bokassa". Africa Today. 25 (3): 25–44. ISSN 0001-9887. JSTOR 4185788.

- "His Imperial Majesty Jean-Bedel Bokassa's Genealogy". Jean-Bedel Bokassa (official cite). Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Titley 2002, p. 89.

- Titley 2002, p. 90.

- "Famous diamonds - Baunat Diamonds". www.baunatdiamonds.com. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- Monday; December 1; AM, 2008 at 2:48. "10 Facts About Diamonds You Should Know". Neatorama. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- Musky 2002, p. 80.

- Titley 2002, pp. 90–91.

- "Mounting a Golden Throne". Time Inc. 19 December 1977. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Titley 2002, p. 92.

- Titley 2002, p. 93.

- Лаврин 1997, p. 93.

- Titley 2002, pp. 93–94.

- Titley 2002, pp. 94–95.

- Николай Алексеев-Рыбин (November 2010). Пятьдесят лет мучительной свободы. Vokrug sveta (in Russian). Vol. 11 no. 2842.

- Titley 2002, p. 95.

- Titley 2002, p. 96.

- Musky 2002, p. 81.

- Musky 2002, pp. 80–81.

- Лаврин 1997, pp. 93–94.

- Titley 2002, pp. 96–97.

- Titley 2002, p. 97.

Bibliography

- Titley, Brian. (2002). Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa. Quebec City: McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 82–98. ISBN 9780773524187.

- Musky, I. A. (2002). 100 великих диктаторов (in Russian). М.: Вече. ISBN 5-7838-0710-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Лаврин А. П. (1997). Словарь убийц (in Russian). М.: AST. pp. 91–95. ISBN 5-15-000252-6.

- Колкер Б. М. (1982). Африка и Западная Европа. Политические отношения (in Russian). М.: Nauka. Ответственный редактор – Л. Д. Яблочков. pp. 141–146.

External links

- Ferdinando Scianna. "Central African Republic. Bangui. 1977 (gallery of photographs, taken during the celebrations of 4–5 December". magnumphotos.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Fragments of the video recording of the coronation of Bokassa on YouTube (from the archive of Werner Herzog)