Congregation Emanu-El of New York

Temple Emanu-El of New York is the first Reform Jewish congregation in New York City and, because of its size and prominence, has served as a flagship congregation in the Reform branch of Judaism since its founding in 1845. Its landmark Romanesque Revival building on Fifth Avenue is one of the largest synagogues in the world. In size, it rivals many of the largest European synagogues such as Grand Choral Synagogue of St. Petersburg, Moscow Choral Synagogue, and the Budapest Great Synagogue.[1] Emanu-El means "God is with us" in Hebrew.

The congregation currently comprises approximately 2,000 families and has been led by Senior Rabbi Joshua M. Davidson since July 2013.[2] The congregation is located at 1 East 65th Street on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The Temple houses the Bernard Museum of Judaica, the congregation's Judaica collection of over 1,000 objects.

History

1845–1926

The congregation was founded by 33 mainly German Jews who assembled for services in April 1845 in a rented hall near Grand and Clinton Streets in Manhattan's Lower East Side. The first services they held were highly traditional. The Temple (as it became known) moved several times as the congregation grew larger and wealthier.

In October 1847, the congregation relocated to a former Methodist church at 56 Chrystie Street. The congregation commissioned architect Leopold Eidlitz to draw up plans for renovation of the church into a synagogue.[3] Radical departures from Orthodox religious practice were soon introduced to Temple Emanu-El, setting precedents which proclaimed the principles of 'classical' Reform Judaism in America. In 1848, the German vernacular spoken by the congregants replaced the traditional liturgical language of Hebrew in prayer books. Instrumental music, formerly banished from synagogues, was first played during services in 1849, when an organ was installed. In 1853, the tradition of calling congregants for aliyot was abolished (but retained for bar mitzvah ceremonies), leaving the reading of the Torah exclusively to the presiding rabbi. By 1869 the Chrystie Street building became the home of Congregation Beth Israel Bikur Cholim.[4][5]

Further changes were made in 1854 when Temple Emanu-El moved to 12th Street. Most controversially, mixed seating was adopted, allowing families to sit together, instead of segregating the sexes on opposite sides of a mechitza. After much heated debate, the congregation also resolved to observe Rosh Hashanah for only one day rather than the customary two.

In 1857 after the death of Founding Rabbi Merzbacher, German speakers still formed a majority of the congregation and appointed another German Jew, Samuel Adler, to be his successor.

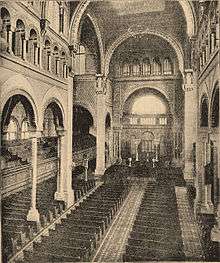

In 1868, Emanu-El erected a new building for the first time, a Moorish Revival structure by Leopold Eidlitz, assisted by Henry Fernbach at 43rd Street and 5th Avenue after raising about $650,000.[6]

The congregation hired its first English speaking rabbi, Gustav Gottheil, in 1873, from Manchester, England.

In 1888, Joseph Silverman became the first American-born rabbi to officiate at the Temple. He was a member of the second class to graduate from Hebrew Union College.

The 1870s and 1880s witnessed further departures from traditional ritual. Men could now pray without wearing kippot to cover their heads. Bar mitzvah ceremonies were no longer held. The Union Prayer Book was adopted in 1895.

Felix Adler, the founder of the Ethical Culture movement, came to New York as a child when his father, Samuel L. Adler, took over as the rabbi of Temple Emanu-El, an appointment that placed him among the most influential figures in Reform Judaism.

In 1924, Lazare Saminsky became music director of the Temple, and made it a center of Jewish music. He also composed and commissioned music for the Temple services.

1926–present

In January 1926, the existing synagogue (built in 1868), was sold to the developer Benjamin Winter, Sr. for $6,500,000 who then sold it to Joseph Durst in December 1926 for $7,000,000.[7][8] In 1927, Durst demolished the building to make room for commercial development.[9]

Emanu-El merged with Temple Beth-El in New York, New York on April 11, 1927, and both are considered co-equal parents of the current Emanu-El. In 1929, the congregation moved to its present location at 65th Street and Fifth Avenue, where the Temple building was constructed to designs of Robert D. Kohn[10] on the former site of the Mrs. William B. Astor House. The vast load-bearing masonry walls support the steel beams that carry its roof. The hall seats 2,500, larger than St Patrick's Cathedral.[11]

By the 1930s, Emanu-El began to absorb large numbers of Jews whose families had arrived in poverty from Eastern Europe and brought with them their Yiddish language and devoutly Orthodox religious heritage. In contrast, Emanu-El was dominated by affluent German-speaking Jews whose liberal approaches to Judaism originated in Western Europe, where civic emancipation had enticed Jews to discard many of their ethnoreligious customs and embrace the lifestyles of their neighbors. For the descendants of Eastern European immigrants, joining Temple Emanu-El often signified their upward mobility and progress in assimilating into American society. However, the intake of these new congregants also helped to slow or halt, if not force a limited retreat from, the 'rejectionist' attitude which 'classical' Reform had espoused towards traditional ritual.

From 1934 to 1947, Dr. Samuel H. Goldenson (1878–1962) was the senior rabbi of Temple Emanu-El. He was president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis from 1933 to 1935.[12]

In 1973, David M. Posner joined the rabbinical staff. Known for his active involvement in the community,[13] he served as the congregation's Senior Emeritus rabbi after his retirement.

Notable members

- Charles Benenson

- Robert A. Bernhard[14]

- Dorothy Lehman Bernhard

- Milton H. Biow

- Leon Black

- Harvey R. Blau[15]

- Paul Block

- Michael Bloomberg

- Lyman Bloomingdale

- Benjamin Buttenwieser

- Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel

- Charles Frohman

- Bernard Gimbel

- Alan "Ace" Greenberg

- David M. Heyman

- Martin Kimmel

- Alfred J. Koeppel

- Andrew Lack

- Adele Lewisohn Lehman[16]

- Herbert H. Lehman

- Irving Lehman

- Solomon Loeb

- Louis Marshall

- Bernard H. Mendik

- William A. Moses[17]

- Adolph Ochs

- Milton Petrie

- Victor Potamkin

- Joan Rivers

- Chester H. Roth[18]

- Simon F. Rothschild[19]

- Frank Russek[20]

- Mel Sachs

- David Sarnoff

- M. Lincoln Schuster

- Sime Silverman

- Carl Spielvogel

- Eliot Spitzer

- Oscar S. Straus

- Lewis L. Strauss

- Sarah Lavanburg Straus

- Harold Uris

- Felix M. Warburg

- Jeff Zucker

References

- Sacred Destinations Largest Sacred Sites in the World Archived 2008-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

- "Emanu-El | Home". Archived from the original on 2020-04-17. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- Rachel Wischnitzer, Synagogue Architecture in the United States, Jewish Publication Society of America, 1955, p. 48

- New York as it was and as it is, Pub. D van Nostrand, New York, 1876,p. 131

- John Disturnell

- Kathryn E. Holliday, Leopold Eidlitz: Architecture and Idealism in the Gilded Age. New York: W. W. Norton, 2008, p. 71 ff.

- The San Bernardino County Sun: "N. Y. Church Site Sold for $7,000,000 for Skyscraper Use" December 15, 1926 | Temple Emanu-El, at the north-cast corner of Forty-third street, conceded to be one of the most valuable pieces of real estate of its size in the world, has been sold to Joseph Durst, vice president of the Capital National bank, at a valuation of $7,000,000, almost $370 a square foot. Mr. Durst plans to erect a 40-story office building on the site when he gains possession In May, 1928. The temple was purchased from the congregation last January by Benjamin Winter, real estate dealer, for $6,500,000.

- The Durst Organization: Timeline Archived 2015-12-25 at the Wayback Machine retrieved July 8, 2012

- The Museum of the City of New York: "Temple Emanu-El" by Lauren Robinson October 11, 2011

- Kohn was working in partnership with Charles Butler and Clarence S. Stein; Mayers, Mauray & Philip consulted.

- (AIA Guide)

- "Samuel H. Goldenson Papers". Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives.

- Lipman, Steve. "'The Consummate Congregational Rabbi'". jewishweek.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- "The Lehmans? They've moved on. Sad? A little". The Forward. 18 September 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "Harvey Blau obituary". Legacy.com. New York Times. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Jewish Women's Archive: "Adele Lewisohn Lehman 1882–1965" by Laurie Sokol retrieved October 30, 2015

- "Paid Notice: Deaths Moses, William A." The New York Times. January 8, 2002.

- "Chester Roth, Dies at 75; Founded Hosiery Concern That Became Kayser‐Roth". The New York Times. July 27, 1977.

- "Simon Rothschild, Merchant Leader, Dies in 75th Year". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 6, 1936.

- "Frank Russek Dies at 73; Founder of 5th Ave. Firm". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 11, 1948.