Comair Flight 5191

Comair Flight 5191, marketed as Delta Connection Flight 5191, was a scheduled United States domestic passenger flight from Lexington, Kentucky, to Atlanta, Georgia, operated on behalf of Delta Connection by Comair. On the morning of August 27, 2006, at around 06:07 EDT,[2]:1 the Bombardier Canadair Regional Jet 100ER that was being used for the flight crashed while attempting to take off from Blue Grass Airport in Fayette County, Kentucky, 4 miles (6.4 km) west of the central business district of the City of Lexington.

A CRJ-100ER in Comair livery similar to the aircraft involved in the accident. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | August 27, 2006 |

| Summary | Runway overrun due to runway confusion |

| Site | Blue Grass Airport, Lexington, Kentucky 38.0379°N 84.6154°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Bombardier CRJ-100ER |

| Operator | Comair (d/b/a Delta Connection) |

| IATA flight No. | OH5191 |

| ICAO flight No. | COM5191 |

| Call sign | COMAIR 5191 |

| Registration | N431CA[1] |

| Flight origin | Blue Grass Airport |

| Destination | Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport |

| Occupants | 50 |

| Passengers | 47 |

| Crew | 3 |

| Fatalities | 49 |

| Injuries | 1 |

| Survivors | 1 |

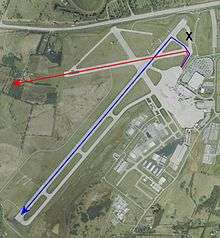

The aircraft was assigned the airport's runway 22 for the takeoff, but used runway 26 instead. Runway 26 was too short for a safe takeoff, causing the aircraft to overrun the end of the runway before it could become airborne. It crashed just past the end of the runway, killing all 47 passengers and two of the three crew. The flight's first officer was the sole survivor.[3][4]

Although not the pilot in command, according to the cockpit voice recorder transcript, the first officer James Polehinke (the only survivor of the crash) was the pilot flying at the time of the accident.[5] In the National Transportation Safety Board report on the crash, investigators concluded that the likely cause of the crash was pilot error.[6]

Flight details

The flight was under the Delta Air Lines brand as Delta Connection flight 5191 (DL5191) and was operated by Comair as flight 5191. It was identified for air traffic control and flight tracking purposes as Comair 5191 (OH5191/COM5191).

The flight had been scheduled to land at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport at 7:18 a.m.

The aircraft involved was a 50-seat Bombardier Canadair Regional Jet CRJ-100ER, serial number 7472.[7] It was manufactured in Canada and was delivered to the airline on January 30, 2001.[2]:14–15

The captain was 35-year old Jeffrey Clay. He had 4,710 flight hours, including 3,082 hours on the CRJ-100.[2]:8–11

The first officer was 44-year-old James Polehinke. Prior to his employment by Comair, Polehinke worked for Gulfstream International as a captain. Polehinke had 6,564 flight hours, including 940 hours as a captain and 3,564 hours on the CRJ-100.[2]:11–14

Crash

The aircraft was assigned the airport's Runway 22 for the takeoff, but used Runway 26 instead. Analysis of the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) indicated the aircraft was cleared to take off from Runway 22, a 7,003-foot (2,135 m) strip used by most airline traffic at Lexington.[8] Instead, after confirming "Runway two-two", Captain Clay taxied onto Runway 26, an unlit secondary runway only 3,500 feet (1,100 m) long,[9] and turned the controls over to First Officer Polehinke for takeoff.[2] The air traffic controller was not required to maintain visual contact with the aircraft; after clearing the aircraft for takeoff, he turned to perform administrative duties and did not see the aircraft taxi to the runway.

Based upon an estimated takeoff weight of 49,087 pounds (22,265 kg),[10] the manufacturer calculated that a speed of 138 knots (159 mph; 256 km/h) and a distance of 3,744 feet (1,141 m) would have been needed for rotation (increasing nose-up pitch), with more runway needed to achieve lift-off.[11] At a speed approaching 100 knots (120 mph; 190 km/h), Polehinke remarked, "That is weird with no lights" referring to the lack of lighting on Runway 26 – it was about an hour before daybreak.[2]:15[12] "Yeah", confirmed Clay, but the flight data recorder gave no indication either pilot tried to abort the takeoff as the aircraft accelerated to 137 knots (158 mph; 254 km/h).

Clay called for rotation, but the aircraft sped off the end of the runway before it could lift off. It then struck a low earthen wall adjacent to a ditch, becoming momentarily airborne,[12] clipped the airport perimeter fence with its landing gear, and smashed into trees, separating the fuselage and flight deck from the tail. The aircraft struck the ground about 1,000 feet (300 m) from the end of the runway.[10] Forty-nine of the 50 people on board perished in the accident; most of them died instantly in the initial impact.[13] The resulting fire destroyed the aircraft.[2]:7

Victims

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Died | Total | Died | Total | Died | |

| United States | 42 | 42 | 3 | 2 | 45 | 44 |

| Canada | 3 | 3 | - | - | 3 | 3 |

| Japan [lower-alpha 1] | 2 | 2 | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 47 | 47 | 3 | 2 | 50 | 49 |

All 47 passengers and two of the three crew members on board the flight died. Comair released the passenger manifest on August 29, 2006.[15]

Most of the passengers were US citizens from the Lexington area, ranging in age from 16 to 72. They included a young couple who had been married the previous day and were traveling to California on their honeymoon.[16]

A memorial service for the victims was held on August 31, 2006, at the Lexington Opera House.[17] A second public memorial service was held on September 10, 2006, at Rupp Arena in Lexington. The Lexington Herald-Leader published a list of the victims with short biographies.[18]

The Flight 5191 Memorial Commission was established shortly after the crash to create an appropriate memorial for the victims, first responders, and community that supported them. The Commission chose the University of Kentucky Arboretum as its memorial site.[19][20][21]

Survivor

James Polehinke, the first officer, suffered serious injuries, including multiple broken bones, a collapsed lung, and severe bleeding. Lexington-Fayette and airport police officers pulled Polehinke out of the wreckage. Polehinke underwent surgery for his injuries, including an amputation of his left leg. Doctors later determined that Polehinke had suffered brain damage and has no memory of the crash or the events leading up to it.[22] As of May 2012, Polehinke was a wheelchair user.[23][24][25] During the same month, Polehinke filed a lawsuit against the airport and the company that designed the runway and taxi lights.[26]

The estates or families of 21 of the 47 passengers filed lawsuits against Polehinke. In response, Polehinke's attorney, William E. Johnson, raised the possibility of contributory negligence on the part of the passengers. When asked by the plaintiffs' attorney, David Royse, what that meant, Johnson replied that they "should have been aware of the dangerous conditions that existed in that there had been considerable media coverage about the necessity of improving runway conditions at the airport."[27] At the time Johnson submitted the contributory negligence defense, he had not yet been able to speak to Polehinke himself. By the time newspapers reported on the court documents, Johnson said he had already told Royse, who criticized the statements, that he would withdraw the argument.[28]

Aftermath

During the course of its investigation, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) discovered that tower staffing levels at Blue Grass Airport violated an internal policy as reflected in a November 16, 2005, memorandum requiring two controllers during the overnight shift: one in the tower working clearance, ground, and tower frequencies, and another, either in the tower or remotely at Indianapolis Center, working TRACON (radar).[29] At the time of the accident, the single controller in the tower was performing both tower and radar duties. On August 30, 2006, the FAA announced that Lexington, as well as other airports with similar traffic levels, would be staffed with two controllers in the tower around the clock effective immediately.[30]

| Wikinews has related news: |

Comair discovered after the accident that all of its pilots had been using an airport map that did not accurately reflect changes made to the airport layout during ongoing construction work. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) later determined that this did not contribute to the accident.[2]:99–100 Construction work was halted after the accident on the orders of Fayette Circuit Judge Pamela Goodwine in order to preserve evidence in the crash pending the inspection by safety experts and attorneys for the families of the victims.[31]

In April 2007, acting on a recommendation made by the NTSB during its investigation of Comair 5191, the FAA issued a safety notice that reiterated advice to pilots to positively confirm their position before crossing the hold-short line onto the take-off runway,[lower-alpha 2] and again when initiating takeoff.[2]:91 And in May, acting on another NTSB recommendation, the FAA advised that pilot training should include specific guidance on runway lighting requirements for take-off at night.[2]:92[32]

The NTSB released several reports on January 17, 2007, including transcripts of the CVR and an engineering report.[33]

In April 2007, the NTSB made four further recommendations, three measures to avoid fatigue affecting the performance of air traffic controllers,[34] and one to prevent controllers from carrying out non-essential administrative tasks while aircraft are taxiing under their control.[35] Although these recommendations were published during the course of the NTSB's investigation into the accident to Comair Flight 5191, they were in part prompted by four earlier accidents, and the board was unable to determine whether fatigue contributed to the Comair accident.

In July 2007, a flying instructor for Comair testified that he would have failed both pilots for violating Sterile Cockpit Rules.[36] Later the same month, the NTSB released its final report into the accident, citing this "non-pertinent conversation" as a contributing factor in the accident.

In July 2008, United States District Judge Karl Forester ruled Delta will not be held liable for the crash, because while Comair is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Atlanta-based airline, Comair maintains its own management and policies, and employs its own pilots.[37] In December of the following year, Forester granted a passenger family's motion for "partial summary judgment" determining, as a matter of law, that Comair's flight crew was negligent, and that this negligence was a substantial factor causing the crash of Flight 5191.[38]

Runway 8/26 on Blue Grass Airport was closed on March 2009, and the new 4,000 foot (1,200 m) runway, runway 9/27, opened on August 4, 2010. This runway has been built on a separate location not connected to the runway 22.[39]

Families of 45 of the 47 passengers sued Comair for negligence. (Families of the other two victims settled with the airline before filing litigation.) Three sample cases were due to be heard on August 4, 2008; but the trial was indefinitely postponed after Comair reached a settlement with the majority of the families. Cases brought by Comair against the airport authority and the FAA, arguing each should share in the compensation payments, are now resolved. The case against the airport authority was dismissed on sovereign immunity grounds, and this ruling was upheld by the Kentucky Supreme Court on October 1, 2009.[40] In Comair's case against the United States, a settlement was reached with the United States agreeing to pay 22% of the liability for the crash, while Comair agreed to pay the remaining 78%.[41]

All but one of the passengers' families settled their cases. After a four-day jury trial in Lexington, Kentucky, that ended on December 7, 2009, the estate and daughters of 39‑year‑old Bryan Woodward were awarded compensatory damages in the amount of $7.1 million.[41] While Comair challenged this verdict as excessive, on April 2, 2010, Judge Forester overruled Comair's objections and upheld the verdict.[38]

The Woodward case, formally known as Hebert v. Comair, was set for a punitive damages jury trial July 19, 2010.[42] In that trial a different jury was to decide whether Comair was guilty of gross negligence that was a substantial factor causing the crash and, if so, the amount of any punitive damages the jury deemed appropriate.[38] The decision to allow a jury trial was reversed in a later hearing, with the judge ruling that the company couldn't be punished for the "reprehensible conduct" of its pilot.[43]

Probable cause

During a public meeting on July 26, 2007, the NTSB announced the probable cause of the accident, as follows:

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the flight crew members' failure to use available cues and aids to identify the airplane's location on the airport surface during taxi and their failure to cross-check and verify that the airplane was on the correct runway before takeoff. Contributing to the accident were the flight crew's nonpertinent conversations during taxi, which resulted in a loss of positional awareness and the Federal Aviation Administration's failure to require that all runway crossings be authorized only by specific air traffic control clearances.[2][44]

NTSB investigators concluded that the likely cause of the crash was that Clay and Polehinke ignored clues that they were on the wrong runway, failed to confirm their position on the runway and talked too much, in violation of "sterile cockpit" procedures.[6] Comair later accepted responsibility for the crash, but also placed blame on the airport, for what it called poor runway signs and markings, and the Federal Aviation Administration, which had only one air traffic controller on duty, contrary to a memo it had previously issued to have two workers on overnight shifts.[45] A judge ruled that, since it was owned by county governments, the airport had sovereign immunity and could not be sued by Comair.[45]

Captain Clay's wife strongly disputes laying primary blame on the pilots, stating that other factors contributed, "including an under-staffed control tower and an inaccurate runway map".[46]

Similar accidents and incidents

In 1993, a commercial jet at Blue Grass Airport was cleared for takeoff on Runway 22 but mistakenly took Runway 26 instead. Tower personnel noticed the mistake and canceled the aircraft's takeoff clearance just as the crew realized their error. The aircraft subsequently departed safely from Runway 22.[47]

In January 2007, a Learjet was cleared to take off at Blue Grass Airport on runway 22, but mistakenly turned onto runway 26. Takeoff clearance was canceled by the local controller prior to the start of the takeoff roll.[48]

On October 31, 2000, the crew of Singapore Airlines Flight 006 mistakenly used a closed runway for departure from Chiang Kai-shek International Airport, Taipei. The Boeing 747-400 collided with construction equipment during the takeoff roll, resulting in the deaths of 83 of the 179 passengers and crew on board.

See also

- Aviation safety

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

- List of sole survivors of airline accidents or incidents

- Western Airlines Flight 2605

- American Airlines Flight 191

Notes

- Both Japanese passengers resided in Lexington[14]

- The hold-short line is the demarcation between the runway and taxiway.

References

- "FAA Registry (N431CA)". Federal Aviation Administration.

- "Attempted Takeoff From Wrong Runway Comair Flight 5191 Bombardier CL-600-2B19, N431CA Lexington, Kentucky August 27, 2006" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. July 26, 2007. NTSB/AAR-07/05. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- "NTSB: Crashed Jet On Wrong Runway". IBS. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2006.

- McMurray, Jeffrey (August 27, 2006). "Comair plane took off from wrong runway". Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 7, 2006.

- "CVR transcript" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. DCA06MA064. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- Ortiz, Brandon (January 25, 2008). "Lawyer claimed 5191 victims shared blame Defense by Co-Pilot to Be Withdrawn". Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- N431CA FAA registration certificate, retrieved June 19, 2008. (Note: CL600-2B19 is the official designation of the CRJ100).

- "NTSB Preliminary Report DCA06MA064". National Transportation Safety Board. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2006.

- "AirNav runway information for KLEX". AirNav. Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- Hirschman, Dave. "Comair flight almost made it". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on February 19, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- "NTSB: LEX Controller Had Two Hours Of Sleep Prior To Accident Shift". Aero-News Network. Retrieved September 1, 2006.

- Wald, Matthew L. (January 18, 2007). "Crew Sensed Trouble Seconds Before Crash". The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2007.

- "Coroner: Most Victims Died on Impact". Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2006.

- "Updated list of Flight 5191 victims"(Archive). Lexington Courier Journal

- Comair. "Passenger Manifest for Flight 5191". Archived from the original on February 16, 2012.

- "Opportunities 'stripped away'". Lexington Courier-Journal. August 2007.

- Mark Pitsch (August 31, 2006). "Several hundred attend memorial service at Lexington Opera House". The Courier-Journal (Louisville).

- Blackford, Linda; Wilson, Amy (September 3, 2006). "The Tragedy of Flight 5191". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. (archived from the original on November 14, 2007)

- "Flight 5191 memorial to be dedicated on fifth anniversary of crash". Lexington Herald-Leader. April 28, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- Ward, Karla (August 2, 2011). "Flight 5191 sculpture unveiling scheduled for Aug. 27". Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- Blackford, Linda B. (August 27, 2011). "400 family and friends of Flight 5191 victims to attend memorial unveiling". Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- "Comair Crash Survivor Leaves Hospital; Co-Pilot, The Lone Survivor Of Kentucky Plane Crash, To Begin Rehabilitation". CBS News. October 3, 2006. Retrieved October 3, 2006.

- "'A horrendous, horrendous tragedy all around'". courier-journal.com. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- WKYT. "For first time, flight 5191 copilot and sole survivor talks about crash". www.wkyt.com. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- CNN Films' 'Sole Survivor': Jim's story, CNN, January 6, 2014, retrieved May 19, 2019

- Ortiz, Brandon (August 28, 2007). "Polehinke Files Suit in Crash: Remembering flight 5191". The Lexington Herald-Leader.

- Comair passengers blamed in crash

- "Culture Wars: Pilot Demise". culturewars.com.

- "FAA memorandum concerning staffing levels" (PDF).

- "FAA: Tower staffing during plane crash violated rules". CNN. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- "Judge orders halt to airport construction". Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved September 15, 2006.

- "NTSB safety recommendations A-06-83/84" (PDF). NTSB. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- "NTSB Advisory". NTSB. Archived from the original on January 20, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2007.

- "NTSB safety recommendations A-07-30/31/32" (PDF). NTSB. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- "NTSB safety recommendation A-07-34" (PDF). NTSB. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- Instructors Testify Flight 5191 Crew Erred Before Crash (Associated Press) – wkyt.com – Obtained April 12, 2011, published, July 19, 2007.

- "Transportation Update July 2008". Business.cch.com. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- IN RE: Air Crash at Lexington, Kentucky, August 27, 2006. justia.com

- "Blue Grass Airport has undergone many changes since crash of Flight 5191". kentucky.com.

- ON APPEAL FROM FAYETTE CIRCUIT COURT V. HONORABLE JAMES D. ISHMAEL, JR., JUDGE Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. kycourts.net (October 1, 2009).

- Voreacos, David (December 23, 2009). "U.S. Helped Delta Insurers Pay $264 Million Crash Settlements – Bloomberg". Preview.bloomberg.com. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- Hewlett, Jennifer (April 20, 2010). "Judge sets July date for Comair trial – Courts". Kentucky.com. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- "Judge rejects pursuit of punitive damages in Comair case" Kentucky.com 3 February 2011 Retrieved March 24, 2011

- "NTSB Press Release, July 7, 2007". National Transportation Safety Board. Archived from the original on October 19, 2007. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- McMurray, Jeffrey (August 2, 2007). "Judge-Comair can't sue airport for crash". USA Today. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- Halladay, Jessie (August 18, 2007). "Comair pilot's widow: His death's a blessing". USA Today. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- "NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System report #256788". NASA. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- "NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System report #722668". NASA. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

External links

| External images | |

|---|---|