Coffeemaker

Coffeemakers or coffee machines are cooking appliances used to brew coffee. While there are many different types of coffeemakers using several different brewing principles, in the most common devices, coffee grounds are placed into a paper or metal filter inside a funnel, which is set over a glass or ceramic coffee pot, a cooking pot in the kettle family. Cold water is poured into a separate chamber, which is then boiled and directed into the funnel. This is also called automatic drip-brew.

History

For hundreds of years, making a cup of coffee was a simple process. Roasted and ground coffee beans were placed in a pot or pan, to which hot water was added and followed by the attachment of a lid to commence the infusion process. Pots were designed specifically for brewing coffee, all to try to trap the coffee grounds before the coffee is poured. Typical designs feature a pot with a flat expanded bottom to catch sinking grounds and a sharp pour spout that traps the floating grinds. Other designs feature a wide bulge in the middle of the pot to catch grounds when coffee is poured.

In about 1889 the infusion brewing process was introduced in France. This involved immersing the ground coffee beans, usually enclosed in a linen bag, in hot water and letting it steep or "infuse" until the desired strength brew was achieved. Nevertheless, throughout the 19th and even the early 20th centuries, it was considered adequate to add ground coffee to hot water in a pot or pan, boil it until it smelled right, and pour the brew into a cup.

There were many innovations from France in the late 18th century. With help from Jean-Baptiste de Belloy, the Archbishop of Paris, the idea that coffee should not be boiled gained acceptance. The first modern method for making coffee using a coffee filter—drip brewing—is more than 125 years old, and its design had changed little. The biggin, originating in France ca. 1780, was a two-level pot holding the coffee in a cloth sock in an upper compartment into which water was poured, to drain through holes in the bottom of the compartment into the coffee pot below. Coffee was then dispensed from a spout on the side of the pot. The quality of the brewed coffee depended on the size of the grounds - too coarse and the coffee was weak; too fine and the water would not drip the filter. A major problem with this approach was that the taste of the cloth filter - whether cotton, burlap or an old sock - transferred to the taste of the coffee. Around the same time, a French inventor developed the "pumping percolator", in which boiling water in a bottom chamber forces itself up a tube and then trickles (percolates) through the ground coffee back into the bottom chamber. Among other French innovations, Count Rumford, an eccentric American scientist residing in Paris, developed a French Drip Pot with an insulating water jacket to keep the coffee hot. Also, the first metal filter was developed and patented by a French inventor.

Types

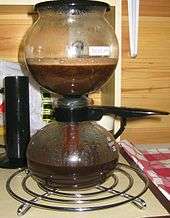

Vacuum brewers

Other coffee brewing devices became popular throughout the nineteenth century, including various machines using the vacuum principle. The Napier Vacuum Machine which was invented in 1840, was an early example of this type. While generally too complex for everyday use, vacuum devices were prized for producing a clear brew and were popular until the middle of the twentieth century.

The principle of a vacuum brewer was to heat water in a lower vessel until expansion forced the contents through a narrow tube into an upper vessel containing ground coffee. When the lower vessel was empty and sufficient brewing time had elapsed, the heat was removed and the resulting vacuum would draw the brewed coffee back through a strainer into the lower chamber, from which it could be decanted. The Bauhaus interpretation of this device can be seen in Gerhard Marcks' Sintrax coffee maker of 1925.

An early variant technique, called a balance siphon, was to have the two chambers arranged side-by-side on a sort of scale-like device, with a counterweight attached opposite the initial (or heating) chamber. Once the near-boiling water was forced from the heating chamber into the brewing one, the counterweight was activated, causing a spring-loaded snuffer to come down over the flame, thus turning "off" the heat, and allowing the cooled water to return to the original chamber. In this way, a sort of primitive 'automatic' brewing method was achieved.

On August 27, 1930, Inez H. Peirce of Chicago, Illinois filed her patent for the first vacuum coffee maker that truly automated the vacuum brewing process, while eliminating the need for a stovetop burner or liquid fuels.[1] An electrically heated stove was incorporated into the design of the vacuum brewer. Water was heated in a recessed well, which reduced wait times and forced the hottest water into the reaction chamber. Once the process was complete, a thermostat using bi-metallic expansion principles shut off heat to the unit at the appropriate time. Peirce's invention was the first truly "automatic" vacuum coffee brewer, and was later incorporated in the Farberware Coffee Robot.

Pierce's design was later improved by U.S. appliance engineers Ivar Jepson, Ludvik Koci, and Eric Bylund of Sunbeam in the late 1930s. They altered the heating chamber and eliminated the recessed well which was hard to clean. They also made several improvements to the filtering mechanism. Their improved design of plated metals, styled by industrial designer Alfonso Iannelli, became the famous Sunbeam Coffeemaster line of automated vacuum coffee makers (Models C-20, C-30, C40, and C-50). The Coffeemaster vacuum brewer was sold in large numbers in the United States during the years immediately following World War I.

Percolators

Percolators began to be developed from the mid-nineteenth century. In the United States, James H. Mason of Massachusetts patented an early percolator design in 1865. An Illinois farmer named Hanson Goodrich is generally credited with patenting the modern percolator. Goodrich's patent was granted on August 16, 1889, and his patent description varies little from the stovetop percolators sold today. With the percolator design, water is heated in a boiling pot with a removable lid, until the heated water is forced through a metal tube into a brew basket containing coffee. The extracted liquid drains from the brew basket, where it drips back into the pot. This process is continually repeated during the brewing cycle until the liquid passing repeatedly through the grounds is sufficiently steeped. A clear sight chamber in the form of a transparent knob on the lid of the percolator enables the user to judge when the coffee has reached the proper colour and strength.

Domestic electrification simplified the operation of percolators by providing for a self-contained, electrically powered heating element that removed the need to use a stovetop burner. A critical element in the success of the electric coffee maker was the creation of safe and secure fuses and heating elements. In an article in House Furnishing Review, May 1915, Lewis Stephenson of Landers, Frary and Clark described a modular safety plug being used in his company's Universal appliances, and the advent of numerous patents and innovations in temperature control and circuit breakers provided for the success of many new percolator and vacuum models. While early percolators had utilized all-glass construction (prized for maintaining purity of flavour), most percolators made from the 1930s were constructed of metal, especially aluminium and nickel-plated copper.

The method for making coffee in a percolator had barely changed since its introduction in the early part of the 20th century. However, in 1970 General Foods Corporation introduced Max Pax, the first commercially available "ground coffee filter rings". The Max Pax filters were named to compliment General Foods' Maxwell House coffee brand. The Max Pax coffee filter rings were designed for use in percolators, and each ring contained a pre-measured amount of coffee grounds that were sealed in a self-contained paper filter. The sealed rings resembled the shape of a doughnut, and the small hole in the middle of the ring enabled the coffee filter ring to be placed in the metal percolator basket around the protruding convection (percolator) tube.

Before the introduction of pre-measured self-contained ground coffee filter rings, fresh coffee grounds were measured out in scoopfuls and placed into the metal percolator basket. This process enabled small amounts of coffee grounds to leak into the fresh coffee. Additionally, the process left wet grounds in the percolator basket, which were very tedious to clean. The benefit of the Max Pax coffee filter rings was two-fold: First, because the amount of coffee contained in the rings was pre-measured, it negated the need to measure each scoop and then place it in the metal percolator basket. Second, the filter paper was strong enough to hold all the coffee grounds within the sealed paper. After use, the coffee filter ring could be easily removed from the basket and discarded. This saved the consumer from the tedious task of cleaning out the remaining wet coffee grounds from the percolator basket.

With the introduction of the electric drip coffee maker for the home in the early 1970s, the popularity of percolators plummeted, and so did the market for the self-contained ground coffee filters. In 1976, General Foods discontinued the manufacture of Max Pax, and by the end of the decade, even generic ground coffee filter rings were no longer available on U.S. supermarket shelves.

Moka pot

The Moka pot is a stove-top coffee maker which produces coffee by passing hot water pressurized by steam through ground coffee. It was first patented by inventor Luigi De Ponti for Alfonso Bialetti in 1933. Bialetti Industries continues to produce the same model under the name "Moka Express".

The Moka pot is most commonly used in Europe and Latin America. It has become an iconic design, displayed in modern industrial art and design museums such as the Wolfsonian- FIU, Museum of Modern Art, the Cooper–Hewitt, National Design Museum, the Design Museum, and the London Science Museum. Moka pots come in different sizes, from one to eighteen 50 ml cups. The original design and many current models are made from aluminium with bakelite handles.

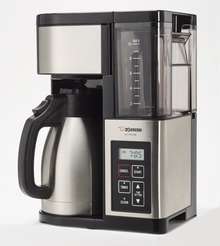

Electric drip coffeemakers

An electric drip coffee maker can also be referred to as a dripolator. It normally works by admitting water from a cold water reservoir into a flexible hose in the base of the reservoir leading directly to a thin metal tube or heating chamber (usually, of aluminium), where a heating element surrounding the metal tube heats the water. The heated water moves through the machine using the thermosiphon principle. Thermally-induced pressure and the siphoning effect move the heated water through an insulated rubber or vinyl riser hose, into a spray head, and onto the ground coffee, which is contained in a brew basket mounted below the spray head. The coffee passes through a filter and drips down into the carafe. A one-way valve in the tubing prevents water from siphoning back into the reservoir. A thermostat attached to the heating element turns off the heating element as needed to prevent overheating the water in the metal tube (overheating would produce only steam in the supply hose), then turns back on when the water cools below a certain threshold. For a standard 10-12 cup drip coffeemaker, using a more powerful thermostatically-controlled heating element (in terms of wattage produced), can heat increased amounts of water more quickly using larger heating chambers, generally producing higher average water temperatures at the spray head over the entire brewing cycle. This process can be further improved by changing the aluminium construction of most heating chambers to a metal with superior heat transfer qualities, such as copper.

Throughout the latter part of the 20th century, many inventors patented various coffeemaker designs using an automated form of the drip brew method. Subsequent designs have featured changes in heating elements, spray head, and brew-basket design, as well as the addition of timers and clocks for automatic-start, water filtration, filter and carafe design, and even built-in coffee grinding mechanisms.

Pourover, water displacement drip coffeemakers

Bunn-O-Matic came out with a different drip-brew machine and in this type of coffeemaker, the machine uses a holding tank or boiler pre-filled with water. When the machine is turned on, all of the water in the holding tank is brought to near boiling point (approximately 200–207 °F or 93–97 °C) using a thermostatically-controlled heating element. When water is poured into a top-mounted tray, it descends into a funnel and tube which delivers the cold water to the bottom of the boiler. The less-dense hot water in the boiler is displaced out of the tank and into a tube leading to the spray head, where it drips into a brew basket containing the ground coffee. The pour-over, water displacement method of coffeemaking tends to produce brewed coffee at a much faster rate than standard drip designs. Its primary disadvantage is increased electricity consumption to preheat the water in the boiler. Additionally, the water displacement method is most efficient when used to brew coffee at the machine's maximum or near-maximum capacity, as typically found in restaurant or office usage. In 1963, Bunn introduced the first automatic coffee brewer, which connected to a waterline for an automatic water feed.

Cafetiere

A cafetiere (Coffee Plunger, French press in US English) requires coffee of a coarser grind than does a drip brew coffee filter, as finer grounds will seep through the press filter and into the coffee.[2] Coffee is brewed by placing the water (heated to 195-205 °F) and coffee together, stirring it and leaving to brew for a few minutes, then pressing the plunger to trap the coffee grounds at the bottom of the beaker.

Because the coffee grounds remain in direct contact with the brewing water and the grounds are filtered from the water via a mesh instead of a paper filter, coffee brewed with the cafetiere captures more of the coffee's flavour and essential oils, which would become trapped in a traditional drip brew machine's paper filters.[3] As with drip-brewed coffee, cafetiere coffee can be brewed to any strength by adjusting the amount of ground coffee which is brewed. If the used grounds remain in the drink after brewing, French pressed coffee left to stand can become "bitter", though this is an effect that many users of cafetiere consider beneficial. For a 1⁄2-litre (0.11 imp gal; 0.13 US gal) cafetiere, the contents are considered spoiled, by some reports, after around 20 minutes.[4] Other approaches consider a brew period that may extend to hours as a method of superior production.

Espresso machine

An espresso machine forces pressurized water through fine grounds to produce a thick, concentrated coffee. Espresso machines may be steam-driven, piston-driven, pump-driven, or air-pump-driven. Machines may also be manual or automatic.

Single-serve coffeemaker

The single-serve or single-cup coffeemaker has gained popularity in recent years.[5] Single-serve brewing systems let a certain amount of water heated at a precise temperature go through a coffee portion pack (or coffee pod), brewing a standardized cup of coffee into a recipient placed under the beverage outlet. A coffee portion pack has an air-tight seal to ensure product freshness. It contains a determined quantity of ground coffee and usually encloses an internal filter paper for optimal brewing results. The single-serve coffeemaker technology often allows the choice of cup size and brew strength, and delivers a cup of brewed coffee rapidly, usually at the touch of a button. Today, a variety of beverages are available for brewing with single-cup machines such as tea, hot chocolate and milk-based speciality beverages. Single-cup coffee machines are designed for both home and commercial use.

Design considerations in coffeemakers

At the beginning of the twentieth century, although some coffee makers tended to uniformity of design (particularly stovetop percolators), others displayed a wide variety of styling differences. In particular, the vacuum brewer, which required two fully separate chambers joined in an hourglass configuration, seemed to inspire industrial designers. Interest in new designs for the vacuum brewer revived during the American Arts & Crafts movement with the introduction of "Silex" brand coffee makers, based on models developed by Massachusetts housewives Ann Bridges and Mrs Sutton. Their use of Pyrex solved the problem of fragility and breakability that had made this type of machine commercially unattractive. During the 1930s, simple, clean forms, increasingly of metal, attracted positive attention from industrial designers heavily influenced by the functionalist imperative of the Bauhaus and Streamline movements. It was at this time that Sunbeam's sleek Coffeemaster vacuum brewer appeared, styled by the famous industrial designer Alfonso Iannelli. The popularity of glass and Pyrex globes temporarily revived during the Second World War, since aluminium, chrome, and other metals used in traditional coffee makers became restricted in availability.

The impact of science and technological advances as a motif in post-war design was eventually felt in the manufacture and marketing of coffee and coffee-makers. Consumer guides emphasized the ability of the device to meet standards of temperature and brewing time, and the ratio of soluble elements between brew and grounds. The industrial chemist Peter Schlumbohm expressed the scientific motif most purely in his "Chemex" coffeemaker, which from its initial marketing in the early 1940s used the authority of science as a sales tool, describing the product as "the Chemist's way of making coffee", and discussing at length the quality of its product in the language of the laboratory: "the funnel of the CHEMEX creates ideal hydrostatic conditions for the unique... Chemex extraction." Schlumbohm's unique brewer, a single Pyrex vessel shaped to hold a proprietary filter cone, resembled nothing more than a piece of laboratory equipment, and surprisingly became popular for a time in the otherwise heavily automated, technology-obsessed 1950s household.

In later years, coffeemakers began to adopt more standardized forms commensurate with a large increase in the scale of production required to meet postwar consumer demand. Plastics and composite materials began to replace metal, particularly with the advent of newer electric drip coffeemakers in the 1970s. During the 1990s, consumer demand for more attractive appliances to complement expensive modern kitchens resulted in a new wave of redesigned coffeemakers in a wider range of available colours and styles.

Unusual designs

Several models of propane gas powered coffee machines are also available.

See also

- Benjamin Thompson

- Caffè crema

- Coffee cup

- Coffee pod

- Coffee preparation

- Coffee vending machine

- ISSpresso – the first espresso coffee machine designed for use in space

- Moka pot

- Tea set

- Teapot

- Teasmade

- Trojan Room coffee pot

References

- "Patent drawing". Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- "Manual brewing techniques give coffee lovers a better way to make a quality drink". www.post-gazette.com. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- "Coffee Brewing - CoffeeResearch.org". www.coffeeresearch.org. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- Rinsky, Laura Halpin (2008). The Pastry Chef's Companion. John Wiley and Sons. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-470-00955-0.

- Gara, Tom (2012-11-28). "The K-Cup Patent Is Dead, Long Live The K-Cup". WSJ. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

External links