Coccolith

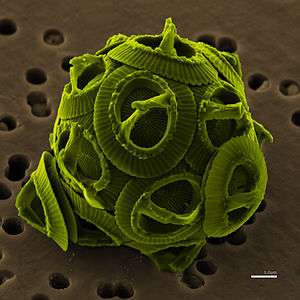

Coccoliths are individual plates of calcium carbonate formed by coccolithophores (single-celled algae such as Emiliania huxleyi) which are arranged around them in a coccosphere.

Formation and composition

Coccoliths are formed within the cell in vesicles derived from the golgi body. When the coccolith is complete these vesicles fuse with the cell wall and the coccolith is exocytosed and incorporated in the coccosphere. The coccoliths are either dispersed following death and breakup of the coccosphere, or are shed continually by some species. They sink through the water column to form an important part of the deep-sea sediments (depending on the water depth). Thomas Huxley was the first person to observe these forms in modern marine sediments and he gave them the name 'coccoliths' in a report published in 1858.[1][2] Coccoliths are composed of calcium carbonate as the mineral calcite and are the main constituent of chalk deposits such as the white cliffs of Dover (deposited in Cretaceous times), in which they were first described by Henry Clifton Sorby in 1861.[3]

Types

There are two main types of coccoliths, heterococcoliths and holococcoliths. Heterococcoliths are formed of a radial array of elaborately shaped crystal units. Holococcoliths are formed of minute (ca 0.1 micrometre) calcite rhombohedra, arranged in continuous arrays. The two coccolith types were originally thought to be produced by different families of coccolithophores. Now, however, it is known through a mix of observations on field samples and laboratory cultures, that the two coccolith types are produced by the same species but at different life cycle phases. Heterococcoliths are produced in the diploid life-cycle phase and holococcoliths in the haploid phase. Both in field samples and laboratory cultures, there is the possibility of observing a cell covered by a combination of heterococcoliths and holococcoliths. This indicates the transition from the diploid to the haploid phase of the species. Such combination of coccoliths has been observed in field samples, with many of them coming from the Mediterranean.[4][5]

Shape

.png)

Coccoliths are also classified depending on shape. Common shapes include:[6][7]

- Calyptrolith – basket-shaped with openings near the base

- Caneolith – disc- or bowl-shaped

- Ceratolith – horseshoe or wishbone shaped

- Cribrilith – disc-shaped, with numerous perforations in the central area

- Cyrtolith – convex disc shaped, may with a projecting central process

- Discolith – ellipsoidal with a raised rim, in some cases the high rim forms a vase or cup-like structure

- Helicolith – a placolith with a spiral margin

- Lopadolith – basket or cup-shaped with a high rim, opening distally

- Pentalith – pentagonal shape composed of five-four sided crystals

- Placolith – rim composed of two plates stacked on top of one another

- Prismatolith – polygonal, may have perforations

- Rhabdolith – a single plate with a club-shaped central process

- Scapholith – rhombohedral, with parallel lines in center

Function

Although coccoliths are remarkably elaborate structures whose formation is a complex product of cellular processes, their function is unclear. Hypotheses include defence against grazing by zooplankton or infection by bacteria or viruses; maintenance of buoyancy; release of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis; to filter out harmful UV light; or in deep-dwelling species, to concentrate light for photosynthesis.

Fossil record

Because coccoliths are formed of low-Mg calcite, the most stable form of calcium carbonate, they are readily fossilised. They are found in sediments together with similar microfossils of uncertain affinities (nanoliths) from the Upper Triassic to recent. They are widely used as biostratigraphic markers and as paleoclimatic proxies. Coccoliths and related fossils are referred to as calcareous nanofossils or calcareous nannoplankton (nanoplankton).

References

- Huxley, Thomas Henry (1858). "Appendix A". Deep Sea Soundings in the North Atlantic Ocean between Ireland and Newfoundland, made in H.M.S. Cyclops, Lieut.-Commander Joseph Dayman, in June and July 1857. London: British Admiralty. pp. 63-68 [64].

- Huxley, Thomas Henry (1868). "On some organisms living at great depth in the North Atlantic Ocean". Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. New series. 8: 203–212.

- Sorby, Henry Clifton (1861). "On the organic origin of the so-called 'Crystalloids' of the chalk". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Ser. 3. 8: 193–200.

- Fortuño, José Manuel; Cros, Lluïsa (2002-03-30). "Atlas of Northwestern Mediterranean Coccolithophores". Scientia Marina. 66 (S1): 1–182. doi:10.3989/scimar.2002.66s11. ISSN 1886-8134.

- Malinverno, E; Dimiza, MD; Triantaphyllou, MV; Dermitzakis, MD; Corselli, C (2008). Coccolithophores of the Eastern Mediterranean sea: A look into the marine microworld. Athens: "ION" Publishing Group. ISBN 978-960-411-660-7.

- Amos Winter; William G. Siesser (2006). Coccolithophores. Cambridge University Press. pp. 54–58. ISBN 978-0-521-03169-1.

- Carmelo R Tomas (2012). Marine Phytoplankton: A Guide to Naked Flagellates and Coccolithophorids. Academic Press. pp. 161–165. ISBN 978-0-323-13827-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coccolith. |

- The EHUX website - site dedicated to Emiliania huxleyi, containing essays on blooms, coccolith function, etc.

- International Nannoplankton Association site - includes an illustrated guide to coccolith terminology and several image galleries.

- Nannotax - illustrated guide to the taxonomy of coccolithophores and other nannofossils.

- Cocco Express - Coccolithophorids Expressed Sequence Tags (EST) & Microarray Database

- Possible functions of Coccoliths