Ci Durian

Ci Durian (Durian River), or Ci Kandi,[lower-alpha 1] is a river in the Banten province of western Java, Indonesia. It rises in the mountains to the south and flows north to the Java Sea. The delta of the river, now canalized, has long been used for rice paddies and for a period was also used for sugarcane plantations. Extensive irrigation works diverted water from the river into a canal system in the 1920s, but these works were not completed and suffered from neglect in the post-colonial era. Plans were made in the 1990s to rehabilitate the irrigation works and dam the river to provide water for industrial projects, with Dutch and Japanese assistance, but these were cancelled by the Indonesian government.

| Ci Durian | |

|---|---|

Bridge over the Cidurian 1915–26 | |

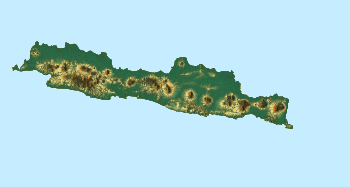

Location in Java | |

| Location | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Java |

| Mouth | |

• location | Tanara |

• coordinates | 6°01′27″S 106°24′42″E |

| Basin features | |

| Geonames | Ci Durian at GEOnet Names Server |

Location

The Ci Durian rises on the slopes of the 1,929 metres (6,329 ft) high Mount Halimun and flows northward through the Banten region. It reaches the coast to the east of Kota Banten.[3] The rivers in Banten, the westernmost province of Java, run roughly parallel to each other. The main ones are the Peteh, called the Banten on the lower reaches near the city of Kota Banten, the Ujung, which enters the sea at Pontang, the Durian, which enters the sea at Tanara, the Manceuri, and the Sadane, which rises in the mountainous region of Priyangan and in 1682 formed the border between the Dutch East India Company (VOC) territory and Batavia (modern Jakarta).[4] The Durian, Manceuri and Sadane rivers flow through the Tangerang Plain.[5] The rivers fan out into deltas near the coast. There are marshes between the mouth of the Durian at Tanara and the mouth of the Sadane.[4]

History

The original inhabitants of the mouths of Ci Ujung, Ci Durian and Ci Banten rivers were Sundanese people.[6] In 1682 there were paddy fields on the lower reaches of the Ujung and Durian.[7] After 1700 sugar production in Banten was revived, mostly in the swampy Ci Durian delta, which had the water needed to grow sugarcane. This project was organized by the Chinese entrepreneur Limpeenko, a merchant who lived in Batavia and regularly visited the Banten Sultanate, bringing luxury fabrics for the Sultan's court. Limpeenko obtained a number of leases from the sultan in 1699.[8] At this time the area at the mouth of the Durian was sparsely populated, with the original inhabitants living by fishing and some agriculture. Their way of life remained unchanged with the rise of sugar production. Newcomers such as Malays settled without permission in the area to work the sugar plantations, but the bulk of the labor force was Chinese from Batavia.[8]

In 1808 the part of the Banten Sultanate to the east of the Ci Durian (or Ci Kandi) was ceded to the Dutch.[9] This territory became part of the Dutch-controlled Banten Province, whose western border was defined by the Ci Durian, which now separated the province from the Banten Sultanate.[10] The Dutch government leased the land to the east of the Ci Durian to private Dutch people.[11] The last titular sultan of Banten was removed in 1832, but in 1836 a rebellion broke out in Ci Durian Ilir that was put down by force. Another rebellion in Ci Durian Udik was suppressed in 1845.[12] After a final revolt elsewhere in Banten in 1850 there was quiet for 30 years, when a terrible plague broke out, followed by the disaster of the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa.[12]

The Tjikandi district in 1890 consisted of the privately owned Tjikandi üdik and Tjikandi Ilir. [13] The river was accessible by barges and river boats from its mouth up to Tji-Kandi-Ilir.[14]

Irrigation works

The Tangerang Plain was still owned by private landlords in the early 20th century. The farmers grew low-quality rice, mostly using rainfall-based water storage and irrigation systems that depended on the whims of landlords for functioning of key components, with arbitrary water distribution. They suffered from poverty and famine or food shortages.[5]

In 1911 the colonial government started to prepare an irrigation plan, and in 1914 determined that various tracts in the plain should be subject to compulsory purchase for this purpose. In 1919 a plan was issued where the north of the plain would be irrigated by the Ci Sadane and the southern area by the Ci Durian.[15] This plan assumed that a movable weir would be built on the Ci Durian at Solear Desa, but cost estimates showed it would be cheaper to build a permanent weir further upstream, even though the canal would have to be longer.[16] The Ci Durian River Intake Weir was built by Hollandsche Deton Maatschappij, which was praised for its good work in 1926. Sixty years later the masonry was still in excellent condition.[17] Further work resulted in plans to extend the main Ci Durian canal further east, across the Ci Manceuri river.[18]

Planned extensions to the Ci Durian irrigation network were delayed in the post-colonial era, as were repairs to the existing works. The planned viaduct over the Ci Manceuri was not completed until the 1970s.[19] The existing works were not renovated until 1988–92. By this time the irrigated area was 10,400 bouws,[lower-alpha 2] compared to the earlier estimate of 17,000 bouws.[19] Apart from the masonry the works were in extremely poor repair, particularly the steel equipment.[17] In 1989 two reports were published on the Ci Durian Ugrading and Water Management Project.[20] Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) undertook the Ci Ujung – Ci Durian Integrated Water Resources Study in 1992. There were advanced plans to build dams on these two rivers to supply water to industrial developments at Bojonegara and nearby places.[21]

A 1993 study of irrigation in Indonesia, based on detailed data from the Ci Durian Upgrading and Water Management Project, concluded there were serious imbalances between upstream and downstream water users, finding that downstream users sometimes had to raid upstream facilities at night to get a temporary release of water.[22] However, the Indonesian government made an abrupt decision to cancel the project and all others funded by Dutch aid.[23]

A 1994 report said the Environmental Impact Control Agency had checked on untreated waste being dumped by the P. T. Indah Pulp and Paper Company into the Ci Durian River. They found that although the company had built an advanced facility for treating waste water, it was not used at night, when untreated waste was released into the river.[24]

See also

Notes

- The river is also known as Chi Kandi, Tji Kande, Tji Durian, Tjidoerian and Tjidurian.[1] Thus an 1890 German book on Java lists the main rivers of the north coast as Tji-Udjong (Pontang), Tji-Durian (Tjikandi), Tji-Dani (Tangerang), Tji-Liwong, Tji-Tarum, Tji-Manuk, Kali Demak (Sampangan), Kali Tanggul Anggin, Kali Solo (Bengawan), and Kali Brantas (Kediri).[2]

- 1 bouw) was equal to 7,096.5 square metres (76,386 sq ft), so 10,400 bouws would be 7,380.36 hectares (18,237.3 acres).

References

- Chi Kandi – Getamap.

- Schulze 1890, p. 13.

- Atsushi Ota 2014, p. 168.

- Talens 1999, p. 40.

- Kop, Ravesteijn & Kop 2016, p. 298.

- Ensiklopedi Umum.

- Talens 1999, p. 43.

- Talens 1999, p. 78.

- Atsushi Ōta 2006, p. 13.

- Atsushi Ota 2014, p. 167.

- Atsushi Ōta 2006, p. 208.

- Schulze 1890, p. 465.

- Schulze 1890, p. 141.

- Schulze 1890, p. 139.

- Kop, Ravesteijn & Kop 2016, p. 299.

- Kop, Ravesteijn & Kop 2016, p. 303.

- Kop, Ravesteijn & Kop 2016, p. 318.

- Kop, Ravesteijn & Kop 2016, p. 310.

- Kop, Ravesteijn & Kop 2016, p. 314.

- Van der Krogt 1994, p. 98.

- Technology Needs for Lake Management in Indonesia ... UNEP.

- Kalshoven 1994, p. 429.

- Kop, Ravesteijn & Kop 2016, p. 324.

- MacAndrews 1994, p. 379.

Sources

- Atsushi Ōta (2006), Changes of Regime And Social Dynamics in West Java: Society, State And the Outer World of Banten, 1750–1830, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-15091-9, retrieved 27 January 2017

- Atsushi Ota (21 November 2014), "Toward a Transborder, Market-Oriented Society. Changes in the Hinterlands of Banten, c.1760–1790", Hinterlands and Commodities: Place, Space, Time and the Political Economic Development of Asia over the Long Eighteenth Century, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-28390-9, retrieved 27 January 2017

- "Chi Kandi", Getamap, retrieved 2017-01-27

- "Banten", Ensiklopedi Umum (in Indonesian), Kanisius, 1973, ISBN 978-979-413-522-8, retrieved 27 January 2017

- Kalshoven, Geert (1994), "Access to Water; A Socio-Economic Study into the Practice of Irrigation Development in Indonesia by A. Schrevel", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Deel: Brill, 150, JSTOR 27864561 – via JSTOR

- MacAndrews, Colin (April 1994), "Politics of the Environment in Indonesia", Asian Survey, University of California Press, 34 (4): 369, doi:10.2307/2645144, JSTOR 2645144

- Kop, Jan; Ravesteijn, Wim; Kop, Kasper (21 March 2016), Irrigation Revisited: An anthology of Indonesian-Dutch cooperation, Eburon Uitgeverij B.V., ISBN 978-94-6301-028-3, retrieved 27 January 2017

- Schulze, L. F. M. (1890), Führer auf Java: Ein Handbuch für Reisende. Mit Berücksichtigung der Socialen, commerziellen ... (in German), Publisher Kolff & Co ; Seyffardt 'sche Buchhandlung, retrieved 2017-01-27

- Talens, Johan (1 January 1999), Een feodale samenleving in koloniaal vaarwater: staatsvorming, koloniale expansie en economische onderontwikkeling in Banten, West Java (1600–1750) (in Dutch), Uitgeverij Verloren, ISBN 90-6550-067-7, retrieved 27 January 2017

- Technology Needs for Lake Management in Indonesia – Investigation of Rawa Danau and Rawa Pening, Java, UNEP: United Nations Environment Programme. Division of Technology, Industry and Economics, retrieved 2017-01-27

- Van der Krogt (1994), "OMIS: a model package for irrigation", Irrigation Water Delivery Models: Proceedings of the FAO Expert Consultation, Rome, Italy, 4–7 October 1993, Food & Agriculture Org., ISBN 978-92-5-103585-6, retrieved 27 January 2017