Church of St Mary Magdalene, Newark-on-Trent

The Church of St Mary Magadalene, Newark-on-Trent is a parish church in the Church of England in Newark-on-Trent in Nottinghamshire. There has been a church on this site for nearly 1,000 years. The present church is built in the Gothic style, with parts dating from the 12th century. St Mary Magdalene's is one of the largest parish churches in England and is regarded as one of the finest.[3] It is a Grade I listed building.

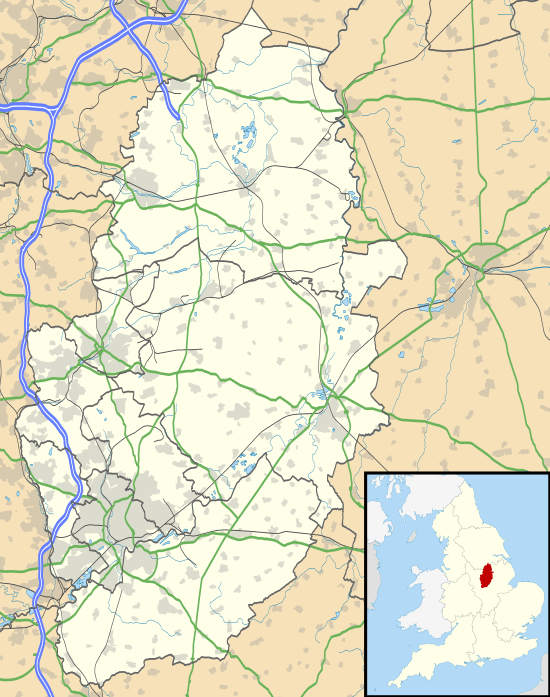

| St Mary Magdalene's Church Newark-on-Trent | |

|---|---|

Parish Church of St Mary Magdalene | |

St Mary Magdalene's Church Newark-on-Trent Location within Nottinghamshire | |

| 53°04′36″N 00°48′30″W | |

| Location | Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Broad church |

| Website | stmnewark.org |

| History | |

| Dedication | St Mary Magdalene |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed[1] |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 215 feet (66 m) |

| Width | 116 feet (35 m) |

| Nave width | 73 feet (22 m) |

| Spire height | 236 feet (72 m) |

| Bells | 10 |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Newark with Coddington |

| Deanery | Newark and Southwell[2] |

| Archdeaconry | Newark |

| Diocese | Southwell and Nottingham |

| Province | York |

| Clergy | |

| Priest in charge | Revd David Pickersgill |

| Curate(s) | Revd Chris Lee |

| Laity | |

| Organist/Director of music | Stephen Bullamore |

In the early 21st century, St Mary Magdalene's is an active parish church, with nine services per week and serving the community with youth and children's programs.[4] The church has a bells, fine organ and a choir founded in 1532.[5]

In his 2009 book England's Thousand Best Churches, Simon Jenkins awards St Mary's four stars and says: "Built over the two centuries of Perpendicular ascendancy after the Black Death, it piles high above its constricted urban site. A style so often dull is here exhilarating, the vistas mystic, the furnishings rich... The Nave is a wonder of proportion. Pevsner attributes this to the old Decorated plan, giving the aisles breadth, while the later masons added height."[6]

History

The present church is the third on this site. A Saxon church stood on the site, in the manor of the Earl of Mercia, who died in 1057, and his wife Lady Godiva, but nothing of that structure now remains. Newark had been granted by the Earl to the monks of Stow.[7]

In about 1180 the church was substantially rebuilt, with a crypt that still exists. The piers of the crossing, and the west tower date from circa 1220, with the spire being about 100 years later. The greater part of the church- the nave with its aisles and clerestory, and the chancel are 15th century, with transepts and chapels added in the early 16th century. The mid 19th century saw a thorough restoration by Sir George Gilbert Scott, and further restoration was made in the 20th century by Sir Ninian Comper and others.[1]

Architecture

The Church of St Mary Magdalene, Newark, is a large Gothic church, with aisled and clerestoried nave and chancel, transepts, and a single tower topped by a spire, at the western end. On the south side is a two-storey porch with a library over it. There is a vestry to the side of the south chancel aisle. The exterior has crenellated parapets, except, on the south aisle, where the west end terminates n a large gable and is set with a tall window, making the west front asymmetrical.[1] The material is ashlar masonry.

Tower

The west tower, rises at the end of the nave, framed by the ends of the aisles. It dates from about 1220, and is in the Early English Gothic style, with simple lancet openings and arcading but set with a later large window with Perpendiciular tracery. The 14th century spire is octagonal and rises to (236 feet (72 m), the highest in Nottinghamshire[8] and reputed to be the fifth tallest in the UK.[9] There is a visible hole in the spire which is claimed to have been made by a musket ball during the Civil War.[8]

The tower holds a peal of ten bells by John Taylor & Co of Loughborough dates from 1842.[10] The tenor is in C at 533.5 Hz and weighs 31cwt, 1qr, 11 lb (3,511 pounds (1,593 kg)).

For many years the clock in the tower of St Mary Magdalene's was the only chronicler of hours in the town with the exception of one at Nicholson's foundry.[11] By the end of the 19th century it was erratic, and a new clock was gifted by the Mayor, Alderman B. Tidd Pratt, and set going on 14 July 1898.[12] It has three 7-foot (2.1 m) diameter and one 9-foot (2.7 m) diameter roman gilded skeleton dials and a mechanism by Joyce of Whitchurch, dated 1898. It sounds Westminster Quarters. It was converted to electrical power, in 1971, by Smith of Derby, with direct drive on chime and strike and autowind on the going train.[13]

Interior

The central piers remain from the previous church, dating from the 11th or 12th century. The upper parts of the tower and spire were completed about 1350; the nave dates from between 1384 and 1393, and the chancel from 1489.

The sanctuary is bounded on the south and north by two chantry chapels, the former of which has on one of its panels a remarkable painting from the Dance of Death. There are a few old monuments, and an exceedingly fine brass of the 14th century.

The library above south porch was presented by Bishop White in 1698. On the north wall hangs the oil painting The Raising of Lazarus by William Hilton RA. It was previously used as an altarpiece for the High Altar.

The chapel of St George was decorated by W.D. Caroe around 1920. The chapel of the Holy Spirit was decorated by Sir Ninian Comper in 1930. The reredos, given in 1937 in memory of William Bradley and his wife Elizabeth, was designed by Sir Ninian Comper.

The church was designated a Grade I listed building, being of outstanding architectural or historic interest, on 29 September 1950.[14]

Restoration

The roofs of the whole of the south aisle, nave and chancel were restored between 1850 and 1852. The whole of the west window was revealed when the floor of the ringing chamber, formerly on a level with the transom of the window, was raised.

The church was heavily restored between 1853 and 1855 by Sir George Gilbert Scott.[1] The plastered ceilings were removed, and replaced with oak. The galleries and pews were removed, the stonework of the pillars, arches and windows was cleaned and repaired. The floor was levelled and concreted and in the nave laid with black and red Minton tiles. The chancel was fitted with encaustic tiles. A new reredos in Ancaster stone replaced Hinton's picture, which was moved to the north transept. The screen had its paint removed, and was restored. The old stalls, miserere seats, and desks were repaired and restored. The organ was moved from the rood loft, and placed in the south chancel aisle, with an entry to the vestry through the middle of it. The windows of the nave and transepts were renewed with Hartley's rough plate glass in quarries. The walls of the nave were lined to the height of six feed with oak panelling. It re-opened for worship on 12 April 1855[15]

The spire was damaged in a lightning strike in May 1894. The weather cock was re-instated on 22 August 1894 witnessed by a large crowd of spectators.[16] The nave roof, south porch and spire were restored in 1913.

Vicars of Newark

- 1301 Walter Adam de Coddington

- 1320 William de Lincoln

- 1322 Rocelinus or Roslyn

- 1333 John de Leverton

- 1349 Thomas de Silkeston

- 1359 Thomas de Westburgh

- 1360 Roger de Leverton

- 1367 William de Nesse

- 1371 Roger de Leverton

- 1375 John de Seggefield

- 1378 John Sharp

- 1421 John More

- 1423 Thomas Marshe

- 1425 Robert Crosslande

- 1425 Nicholas Ferriby

- 1445 John Burton

- 1475 Nicholas Laughton

- 1476 John Tristrop

- 1479 John Smythe

- 1521 Edward Fowke

- 1521 Sampson Lorde

- 1532 Henry Lytherlande

- 1540/2 Robert Chapman

- 1550 Christopher Sugden

- 1554 John Taverham

- 1559 Christopher Sugden

- 1561 Edward Roodes

- 1573 Nicholas Clayton

- 1581 William Smythe

- 1585 Lawrence Staunton

- 1588 Edward Holden

- 1596 William Pell

- 1597 Bryan Vincent

- 1601 Joseph Batts

- 1612 Simon Jacks

- 1618 Edmund Mason

- 1628 Samuel Keemel

- 1629 John Moseley

- 1642 Henry Trewman

- 1655 Samuel Hawkes

- 1660 Thomas White, afterwards Bishop of Peterborough

- 1666 Richard Pearson

- 1667 Henry Smith, Prebendary of Southwell Minster

- 1702 Eli Stanfield

- 1719 Bemard Wilson, D.D.

- 1772 Hugh Wade

- 1776 Charles Fynes

- 1788 Davies Pennell

- 1814 William Bartlett

- 1835 John Garrett Bussell, B.A., Canon of Lincoln Cathedral

- 1874 Josiah Brown Pearson, LL.D. afterwards Bishop of Newcastle (Australia)

- 1880 Marshall Wild, M.A., Canon of Southwell Minster

- 1908 Walter Paton Hindley, M.A., Canon of Southwell Minster

- 1919 James Manders Walker, M.A., D.D., Canon of Southwell Minster

- 1929 William Kay, DSM, M.C., M.A. Canon of Southwell Minster, afterwards Provost of Blackburn Cathedral

- 1936 Alfred Parkinson, B.A., Canon of Southwell Minster

- 1944 Lewis Mervyn Charles-Edwards, afterwards Bishop of Worcester

- 1948 George William Clarkson, M.A., Canon of Southwell Minster, afterwards Bishop of Pontefract

- 1955 John H.D. Grinter, B.A., Canon of Southwell Minster

- 1963 Eric J. Kingsnorth, F.I.A., Canon of Southwell Minster

- 1975 Benjamin Hugh Lewers, M.A., Rector from 1980, afterwards Provost of Derby Cathedral

- 1981 George Miller McMillan Thomson

- 1988 Roger Anthony John Hill, M.A., Canon of Southwell Minster

- 2003 Vivian John Enever

- 2014 Stephen Morris (Priest in charge)[17]

- 2017 David Pickersgill (Priest in charge)

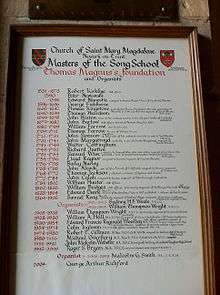

The Magnus Bequest

The church is supported by the Magnus Bequest, a charitable foundation created in the early 1530s by Thomas Magnus, who gave farms and lands in south Yorkshire, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire for a fourfold purpose:

- The establishment and endowment of a free grammar school;[18]

- The provision and endowment of a song school to ensure the maintenance of a high standard of worship in the parish;[19]

- the provision of a sufficient sum to guarantee the efficient administration of the bequest and proper upkeep of the farms and lands from which the income was to be derived;

- the provision of occasional sums to be used for the general well-being of the church or the town (if there be any surplus after the first three objects had been fully accomplished).

Burials

Music

Organ

At the beginning of the 19th century a new organ, by George Pike England, with three manuals, was provided by the trustees of the Magnus, Brown's and Phyllypott's charities at a cost of £1,300. It was opened on 11 November 1804 by Thomas Spofforth.[20]

It was placed on the west gallery from where the choir sang services. In 1814 the organ was re-located on the chancel screen and the choir returned to the chancel. In the 1850s the organ was rebuilt by Forster and Andrews of Hull, provided with a new case and again re-located, this time to its present position in the south choir aisle.

In 1866 the organ was rebuilt and enlarged by Henry Willis. Willis virtually doubled the size of the instrument and its case, creating a large Romantic four-manual organ. The organ was again rebuilt by William Hill & Sons in 1910 at the expense of Mrs Becher Tidd Pratt and family, and subsequently by Hill, Norman and Beard in 1924, 1938, 1964 and 1978 when it was rebuilt and more voices added.

It is now electrically operated by the Ellen Dynamic Transmission system which allows much greater mobility of the organ console, providing more direct contact with the congregation and the choir; it is the first four-manual instrument in the country to be so equipped, enabling a live performance to be electronically recorded and replayed automatically.[21]

The Choir

The Choral Foundation was set up by Thomas Magnus in 1532[18][19] and was said to be the only existing pre-reformation choir outside cathedrals and Oxbridge colleges. Girl choristers were admitted into the main choir from 2008.

In February 2012 choral services stopped following the dismissal of the Master of the Song School.[22] The choir was refounded in 2015. It has an emphasis on the training of young people, supported by the Magnus Bequest.

Masters of the Song School

There have been appointments since at least 1532.

- Robert Kyrkbye[23] 1532–1574

- Peter Newcombe c. 1590

- Edward Manestie until 1596

- George Fishburne 1596–1636?

- Thomas Kingstone 1636–1641

- Thomas Heardson 1642–1649

- John Hinton 1649–1668

- John Barlow 1668 -

- Roland Barlow 1679–1682

- William Farrow 1682–1709

- Thomas Farrow 1709–1712

- John Spencer 1712–1731

- John Murgatroyd 1731–1741

- Walter Cottingham 1741–1749

- Richard Justice 1749–1751

- Samuel Wise 1751–1754, latterly organist of Southwell Minster and St Mary's Church, Nottingham

- Lloyd Rayner 1754–1756, later organist of Lincoln Cathedral

- Bailey Marley 1757–1758

- John Alcock[24] 1758–1768

- Thomas Jackson 1768–1781

- John Calah 1782–1784

- William Hunter 1784–1802

- William Brydges 1802–1835

- Edward Dearle 1835–1864

- Samuel Reay 1864–1901 (formerly organist of St Thomas the Martyr, Barras Bridge, Newcastle upon Tyne

- Sydney Harry Franz Weale FRCO LRAM 1901–1903

- William Thompson Wright ARCO RCM 1903–1928 (formerly organist of St Leonard's Church, Newark)

- William A Hall MusDoc 1928–1930

- Edward Francis Reginald Woolley[25] MA ARCO 1930–1954 (assistant organist at Lincoln Cathedral 1926–1930)

- Colin Ingleson FRCO 1954–1974

- Robert Edward Gillman 1974–1980

- Michael Overbury 1980–1986 (later organist of Worksop Priory)

- John Webster 1986–1992

- Roger Bryan 1992–2006

- Interregnum 2006–2009

- George Richford 2009–2012 (moved to Romsey Abbey)

- Interregnum 2012–2015[26]

- Stephen Bullamore 2015 (Director of Music) [27] -

Concerts

The church hosts several concerts, including a "Music for Market" series at lunchtime on Saturdays.[28]

Assistant organists

- Henry Bramley Ellis ???? - 1864[29]

- Sydney Weale 1901–1903 (formerly assistant of St David's Cathedral, afterwards assistant at Southwell Minster)

- Colin Ingleson FRCO, 1932–1954

- Mike Manners 1982

- Craig Nathan ARCO 1984

- John Shooter ARCO 1985

- Robert Sharpe 1989–1991 (formerly Assistant Organist of Lichfield Cathedral, Director of Music at Truro Cathedral and now Director of Music at York Minster.)

- Charles Harrison 1991-1992 (formerly Assistant Director of Music at Lincoln Cathedral and now Organist and Master of the Choristers at Chichester Cathedral.)

- Donald Hunt 2011–2012 (formerly Organ Scholar of Truro Cathedral (2009–2010) and St Paul's Cathedral, Assistant Organist of St Mary's Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh) (2012-2017)

- Harry Jacques ARCO 2015-2017

- Michael Dutton FRCO

Gallery

- The reredos

- Dance of Death panels

- Chancel roof

- The organ

- West window

- West tower and spire, from the Market Place

From the east, tall seven-light chancel window flanked by two five-light aisle windows, all three from 1498

From the east, tall seven-light chancel window flanked by two five-light aisle windows, all three from 1498.jpg) 15th-century stained glass, south aisle, depicting The Ascension

15th-century stained glass, south aisle, depicting The Ascension

See also

Sources

- Historic England, "Church of St Mary Magdalene and attached railing (1279450)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 22 August 2017

- "St Mary Magdalene, Newark". A Church Near You. The Church of England. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- "Visit Nottinghamshire, St Mary Magdalene, Newark". Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "St Mary Magdalene, Services". Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "St Mary Magdalene, Information for Choristers" (PDF). Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Jenkins, Simon (2009). England's Thousand Best Churches. London: Penguin Books. pp. 604–605. ISBN 978-0-14-103930-5.

- Pask, B. M. (1995), The Parish Church of St, Mary Magdalene, The District Church Council of The Parish Church of St, Mary Magdalene, Newark, ISBN 0-9516888-8-X

- Britain Express. "Newark on Trent, St Mary Magdalene church". Britainexpress.com. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- "Newark St Mary Magdalene - Introduction". Southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- "Newark upon Trent, Notts S Mary Magd". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Dovemaster. 8 July 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "District Notes. Newark". Nottingham Journal. England. 15 April 1898. Retrieved 22 August 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "From Day to Day". Nottingham Journal. England. 18 July 1898. Retrieved 22 August 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- http://southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk/newark-st-mary/hclock.php

- "Church of St Mary Magdalene and Attached Railing". British Listed Buildings.

- "Re-opening of Newark Church". Lincolnshire Chronicle. England. 13 April 1855. Retrieved 22 August 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Newark Church". Nottingham Evening Post. England. 23 August 1894. Retrieved 22 August 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Warm Welcome for Priest". Newark Advertiser. Newark upon Trent. 22 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

The Rev Stephen Morris was welcomed to the town by members of the church and the community.

- "Home page". Newark-upon-Trent, United Kingdom: Magnus Church of England School. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

Magnus Church of England School was formed from the amalgamation of two schools: the Magdalene High School, which was named after Newark's Parish Church, St. Mary Magdalene, and the Thomas Magnus School. Thomas Magnus was Chaplain to King Henry VIII and gave money to start a Grammar School and a Song School.

- "Sing a Song for Newark". Lincolnshire Echo. Lincoln, England: Northcliffe Media. 21 February 2010. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

The Song School or music department at Newark Parish Church has a rich history. Established by Thomas Magnus in 1532, at a time when many choral foundations were being destroyed by King Henry VIII, the original choir consisted of just six men and six boys to sing the daily services.

- "N13568 Version 3.1". National Pipe Organ Register (NPOR). Reigate, United Kingdom: The British Institute of Organ Studies. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- "D06241 Version 3.1". National Pipe Organ Register (NPOR). Reigate, United Kingdom: The British Institute of Organ Studies. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- "Choristers fall silent". Newark Advertiser. Newark-on-Trent, United Kingdom: Advertiser Group Newspapers. 16 February 2012. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Warner, Tim. "Hamlet lay outside the town walls". Newark Advertiser. Newark-on-Trent, United Kingdom: Advertiser Group Newspapers). Retrieved 28 April 2012.

A deed from May, 1507, (quoted by N. G. Jackson in his history of the Magnus) makes reference to a Robert Kyrkbye of Osmundthorpe who was described as a 'singing man' (presumably a music teacher). This is thought to be the same Kyrkbye who became first master of the Magnus Song School from 1532 to 1574.

- "John Alcock (Jun): Eight Easy Voluntaries for the Organ (London 1775)". Greg Lewin Music: New Titles. Bridgnorth, United Kingdom: Greg Lewin Music. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

John Alcock jun (1740–1791) was a chorister under his father at Lichfield Cathedral. He took his BMus degree at Oxford in 1766. He was Organist and Master of the Song School at Newark from 1758 to 1768 and organist of St Matthew's church, Walsall from 1773.

- Who's Who in Music. Shaw Publishing Co. Ltd. London. First Post-war Edition. 1949/50

- "Newark Parish Church's new director looks to musical future". Newark Advertiser. Newark on Trent. 22 June 2014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "New director of music for Newark Parish Church". Newark Advertiser. Newark on Trent. 16 November 2014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Music for Market – Saturday lunchtime concerts in Newark – Royal School of Church Music: Southwell & Nottingham". rscmnotts.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Lincolnshire Chronicle - Friday 11 March 1864

- The Buildings of England, Nottinghamshire, Nikolaus Pevsner

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Mary Magdalene's church, Newark. |

- holytrinitynewark.org

- Saint Mary Magdalene Churchyard at interment.net