Christman Genipperteinga

Christman Genipperteinga was a possibly fictitious German bandit and serial killer of the 16th century. He reportedly murdered 964 individuals starting in his youth over a 13-year period, from 1568 until his capture in 1581.[1][2] The story of Christman Genipperteinga is contained in a contemporary pamphlet from 1581. As early as in 1587, just 6 years after its publication, at least one chronicler included the story as factual.[3]

Similar tales circulated about robbers with names such as Lippold, Danniel, Görtemicheel, Schwarze Friedrich, Henning, Klemens, Vieting and Papedöne. The tale of Papedöne is particularly relevant, since a version of that story is contained in a book published in 1578, 3 years before Genipperteinga's alleged death.

Origins

Christman Genipperteinga came from Kerpen,[4] two miles ("zwo Meylen") southwest of Cologne.[5]

Lair

For about seven years Christman lived in a cave/mine complex some distance ("ein große Meyl") away from Bergkessel (possibly Bernkastel-Kues[4]), in a wooded upland/mountain area called Frassberg.[5] From there, he had a good view over the roads going between Trier, Metz, Dietenhoffen and Lützelburger Landt.[5]

The cave complex is described as being very cleverly built, just like an ordinary house inside, with cellars, rooms and chambers, with all the household goods that ought to belong in a house.[5]

Criminal activity and methods

Historian Joy Wiltenburg identifies two important, occasionally overlapping, patterns of crime reports relative to serial killers in Early Modern Germany:

- Reports on robber-killers[6]

- Reports on witches (for example: mid-wives) or cannibals targeting infants or even fetuses cut out of their mothers' wombs for use of their body parts in feasting or in rituals of black magic.

Genipperteinga fits pattern 1, hoarding his ill-gotten gains in his cave.[7] As Wiltenburg further remarks, however:[2]

"Christman Genipperteinga was unusual in apparently maintaining the same stationary den throughout his years of serial killing. More often, accounts tell of robbers' traveling, meeting, and congregating with other robbers or with the Devil on their journeys."

Furthermore, in contrast with the reports of other robber killers from that time, like those of Peter Nyersch and Jacob Sumer,[2] depictions of supernatural abilities and/or contracts with the devil are absent from the 1581 account of Christman. He is also definitely reported as guilty of multiple infanticides, but the account from 1581 does not connect this with practice of black magic or cannibalism.

Christman preyed upon both German and French travelers. It was said that a party of 3, 4, or even 5 travellers might not be safe from him.[7] Nor was he averse to double-crossing his own partners in crime in order to get his hands on the whole booty, rather than his "just share". Once they had helped bring the loot to his cave, he served them poisoned food or drink, with rarely anyone surviving beyond 5 hours. He is said to have thrown their bodies into a mine shaft connected with his cave complex.[8]

Sex slave

Shortly after he took up residence at Frassberg, Christman met an intended victim, the young daughter of a cooper in Popert. She was traveling to Trier to meet her brother. He changed his mind and ordered her under death threats to come and live with him. He made her swear she would never betray him, and for the next 7 years, she served his sexual wants. Whenever he went out to find new victims, he bound her with a chain so that she could not escape. He fathered 6 children with her[7] but at birth he killed them, pressing in their necks (original: "hat er den Kindern das Genick eingedrückt").[9]

Christman used to hang up their bodies, and stretched them out (orig: "aufgehängt und ausgedehnt"). As the wind made the little corpses move, he said:

"Tanzt liebe Kindlein tanzt, Gnipperteinga euer Vater macht euch den Tanz"

("Dance, dear little children, dance, Gnipperteinga your father is making the dance for you")[8]

Downfall

Christman finally relented to the woman's repeated pleadings that she might be allowed to meet other people, and granted her expressed wish to visit Bergkessel under condition of a renewed oath not to betray him. But once there, seeing the little children running about in the streets, she had a breakdown, and went down on her knees in lamentation:[8]

Allmächtiger Gott dir ist alle ding wohl bewusst auch mit welch Eid ich mich verpflicht habe dass ichs keine Menschen wölle offenbaren so will ichs jetz und diesem (Stein[10]) klagen mein anligen und not denn ichs jetzt und in das siebende Jahr erlitten habe und auch an meinem eignen Fleisch und Blut täglichen muss sehen

(Almighty God! You know of all matters, including the oath I am bound to concerning what I should not reveal to any human. So now I will wail over my condition (to this stone[10]) and despair that I for the seventh year have suffered, and what I have had daily to witness upon my own flesh and blood)[11]

And she began to wail and weep bitterly. Many commiserated with her, but when anyone asked her about what her troubles were, she refused to reveal them. Brought before the mayor, she was urged to tell her story, and assured by many learned men, by reference to Scripture, that if it was a matter of life and the soul, then she ought to confess. She then confessed everything she knew. In order to catch Christman off guard, the following scheme was hatched:[11] She was given a sack of peas, and with these, she marked the way to the cave complex.[12]

On 27 May 1581, 30 armed men set out to capture him. He was asleep when they came, because she had made him relax with gentle words while she deloused his hair. As the armed men barged in, Christman cried out: "Oh, you faithless betrayer and whore, had I known this, I would have strangled you long ago".[12]

Within Christman's cave complex, an immense amount of booty was found, in the form of wine,[5] dried and/or salted meat,[5] suits of armour, firearms and other weaponry,[5] trade goods,[7] coin and other valuables.[7] The value was estimated as exceeding 70,000 Gulden.[2][7] The author of the 1581 Herber account notes that one might well have made a full year's market out of the booty found in Christman's cave.[7]

Confession, trial and execution

Christman kept a diary in which he detailed the murders of 964 individuals, as well as a tally of the loot gained from them. The diary was found among his possessions.[5] In addition to this evidence Christman readily admitted to the murders, adding that if he had reached his goal of a thousand victims, he would have been satifisfied with that number.[2][4][7]

On 17 June 1581[13] Christman Genipperteinga was found guilty,[12] and was condemned to death by the breaking wheel. He endured nine days on the wheel prior to expiring, kept alive in his sufferings with strong drink every day, so that his heart would be strengthened.[12]

Depiction

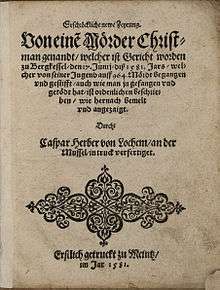

The primary source regarding Christman Genipperteinga is a pamphlet published by Caspar Herber in 1581, Erschröckliche newe Zeytung Von einem Mörder Christman genandt ("Terrible, new tidings about a murderer named Christman"). The publisher of the pamphlet is credited on the title page[13] to come from Lochem an der Mussel. Bergkessel is referred to as "our town" ("unsere Stadt") in the text.[5]

At the time of the pamphlet's end of writing, the loot from Christman's cave as well as his woman were kept at a certain location, the fates of both undecided.[12]

The tale was reprinted in full, with some editing and modernizing of language, by the antiquarian Johann Scheible in 1847.[10]

Literary and social context

The historian Joy Wiltenburg, in Crime and Culture in Early Modern Germany (2012) performed a close study of the popular crime reports from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Her primary aims are to investigate where and how such works were produced, who had authored them, who read and collected such reports, and what particular crimes were principal concerns in these works, and how such questions may have had different answers for different times. Only tangentially does she seek to probe the authenticity of the individual, conserved crime reports, that is, resolving the problem of how the discourse of crime accurately, or inaccurately, portrayed actual crime on the local scale. As noted by her,[2] concerning Early Modern Germany, it was in the 1570s that reports of robber bands multiplied, reaching a peak in the 1580s. Furthermore, she observes:[14]

Economic conditions for the poor (...) worsened notably after about 1570. At the same time that inflation cut increasingly into real wages, climatic change brought a period of unusually harsh weather. In the Little Ice Age that started in the 1570s and continued into the first decades of the seventeenth century, harvest failures caused severe hunger and disease. Reports of crime, such as witchcraft, reached their height during this period of most intense social dislocation.

The story of Christman Genipperteinga belongs therefore, in a literary and social context in which such reports were particularly frequent, relative to immediately preceding or succeeding periods, and should be interpreted with that in mind. For example, as Wiltenburg points out, the peak in report survival from the 1580s is partially explained by the 1588 death of report collector Johann Wick, whereas the historical context from other sources does not yield evidence for a comparable decline of crime in the 1590s relative to the 1580s.[14] A contemporary witness who confirms the large increase in such reports was the preacher Leonhard Breitkopf. In a sermon from 1591, he wrote:[15]

When I was still young, forty or fifty years ago, there was not so much known about all the horrible deeds of murder, such as nowadays are described every year in all sorts of papers

Although Wiltenburg acknowledges that there may well have been an increase in crime in the latter quarter of the sixteenth century, she cautions a framing and delimiting of that increase, with respect to murders in particular, relative to the immediately preceding 16th century, rather than stretching it much further back in time. In particular, one cannot say, with any degree of certainty, that there were more homicides committed in the Early Modern Age than in Late Medieval times. For example, she states:[14]

The late Middle Ages may well have been the heyday of homicide.

One important reason behind this discrepancy, apart from those connected with how new printing methods enabled more reports on crime to be published relative to earlier periods, is the new role of the Early Modern State in actively pursuing, publicizing and punishing crimes, rather than the passive role of the Medieval State, content with arbitration or mediation between aggrieved parties. If no one actively accused another person for a given injury/crime, then no crime existed in the eyes of the medieval authorities. This passive, accusation-dependent system of justice was gradually replaced with the more active, independently investigative and inquisitorial system of justice in the Early Modern period.[14]

Comparing Genipperteinga's time with earlier times, Wiltenburg makes the following pertinent observation relative to the changes in the social composition of the archetypically presented lawless/violent men of previous eras to those from the latter quarter of the 16th century:[2]

A particular urbanite concern in the High/Late Middle Ages were the depredations caused by lawless/feuding nobles:

(...) discussion of crime appeared (...) notably in urban chronicles, a late medieval genre with its own distinctive aims. Beginning in the fourteenth century and into the sixteenth, members of urban elites produced such records, for various purposes, but mainly to serve the political interests of the semi-independent imperial cities. Most paid scant attention to the crimes committed by ordinary people, focusing instead on crimes with political significance. This raised the profile of violent nobles as a dangerous class and contributed to late medieval criticism of feuding. When compared with the picture of crime that emerged in later popular print, they show how differences in genre as well as change over time could shape perceptions of crime.

The 16th century contrast to this earlier picture of "the lawless noble" is borne out by the following observations of Wiltenburg:

In popular crime publications of the sixteenth century, however, the nobility is largely tamed—a sign of both historical change and a shift in genre. While chronicles served the purposes of the urban authorities, and reformers' critiques might address mainly the very elites they hoped to reclaim, popular printing about crime had a far more miscellaneous clientele. Here, respect for social superiority was very much the norm.

The few nobles who appear in crime accounts of the sixteenth century are mainly on the right side of the law, protecting the weak and ensuring that justice is carried out. They figure among the admirable authorities who track down criminals and defend public security.

If the nobility was depicted as mostly harmless or even beneficial, this was not true of another traditional source of danger: the rootless poor. (...) Outsiders and vagrants, already recognized as potentially disruptive, were increasingly demonized. (...) Many worried that loose and ungoverned elements would foment crime, and vagrants were frequently arrested for theft and other offenses that most modern societies deem petty. They were also more likely to be executed than were settled residents.

Thus, the report of Christman Genipperteinga appeared at a time when particular fears of the savage Outsider in the Wild were at their most acute, and when people generally regarded the Criminal as coming primarily from the idle, roaming poor, in contrast to previously primary concerns of haughty, predatory nobles, their brutal, willing henchmen and corrupt magistrates who chose to ignore the crimes committed by the former.

However, Wiltenburg cautions against a general, facile dismissal of sixteenth century tales of murder and mayhem (to which genre Genipperteinga's story belongs) as if they merely were to be considered as literary fictions or as pieces of state propaganda:[2]

The topical crime accounts that flowed from the early presses were not fiction. Although some sloppily borrowed language from accounts of similar crimes elsewhere, very few seem to have been wholly invented.(...) Nevertheless (...) they both mirrored and altered the picture of actual crime (...) Partly by selection and partly by their modes of representation, they reshaped events to reflect cultural conceptions. This process did not necessarily request conscious manipulation, rather, it flowed naturally from the selection of, and reaction to, the crimes considered most worthy of attention.

That being said, it cannot be denied that it was, at this time, a definite trend of sensationalism, and that some wholly untrue stories were produced and sold. In the words of the 19th century German historian Johannes Janssen:[16]

In order to keep a up a constant supply of fresh news, ... the most frightful crimes were invented, and so little fear was there of investigation that they even printed in Augsburg "horrors said to have happened at Munich, but of which nobody there had heard a word" ... In a document signed with the Munich town seal the council replied that the whole report was a deliberate lie

Nor is it only modern historians like Janssen and Wiltenburg who display a measured, if not necessarily wholesale, skepticism towards the actual veracity of crime reports from this time. Already 40 years prior to Genipperteinga's supposed death, in his 1538 Chronica, the humanist and historian Sebastian Franck laments:[17]

Whereas, nowadays, it is, alas! permitted to everyone to lie, and the world shuts its eyes and nobody takes any notice, or asks how or wherewith money has been got of the public, or what is said, written or printed, it has at last come to this, that when writers have no more money they invent some wonderful tale that they sell as a true story ... The consequence is that historians can no longer be sure that what they may hand on as truth, for among all the books floating about there is no warrant for their trustworthiness

Later folklore

Whatever actual truth value attaches to the account of Genipperteinga as related by Caspar Herber, the fact that the pamphlet was published in the same year as Genipperteinga is to have been executed, necessitates the view that Herber's account is among the earliest sources for the story about him in particular. Furthermore, within just a few years after the publication of the story in 1581, it was included as factual in calendars and annals, like those of Vincenz Sturm and Joachim von Wedel. Herber's account is, however, not the only telling of the tale that has circulated, and in this section a review will be given how the story has mutated throughout time, by noting deviations in them, relative to Herber's.

- Christian Gnipperdinga

In Vincenz Sturm's (1587) continuation of Andreas Hondorff's "Calendarium Sanctorum et historiarum", in his entry for 17 June, the verdict of the murderer Christian Gnipperdinga is recorded as one of those significant events happening on that date. Some minor variant details occur relative to Herber, like the murderer's name, that "Burgkessel" was "zwo Meylen" distant from Cologne, that the booty was on 7000 Gulden (rather than 70.000), and that the maiden is said to be from Burgkessel, rather than from Boppard, and was on her way to Cologne, rather than to Trier when Gnipperdinga met her. Apart from that, Sturm's account is merely a condensation of the pamphlet, which he notes was printed in Mainz.[18]

- Christoff Grippertenius

Joachim von Wedel[19] was a Pomeranian gentleman who wrote the annals of the most significant events in Pomerania of his time. He saw fit, however, to include sufficiently remarkable events from elsewhere. In his entry for 1581, a short notice of Christoff Grippertenius is included, with no geographical details given, but asserting that the 6 infants killed were in addition to the 964, an interpretation not forbidden by Herber's account, but not directly cited from it.[20]

- Christoff Gnippentennig

In his 1597 manuscript, Julius Sperber[21] noted that Christoff Gnippentennig at Bergkesel murdered 964 people in addition to six of his own children.[22]

- Christmann Gropperunge, the cannibal

Johann Becherer, in his (1601) "Newe Thüringische Chronica", is an early source on cannibalism, stating that Christman Gropperunge von Kerpen ate the hearts of his infants. That feature is absent from Herber's account. Furthermore, "Frassberg" has become "Frossberg", and from the height above his lair, Christman is said to be able to view the roads to Saarbrücken, Zweybrück, Simmern, Creutzenach and Bacharach, in addition to those mentioned by Herber.[23] Martin Zeiller, in his 1661 "Miscelllania" has Becherer as explicit source for his own brief notice, rather than Herber.[24] In his 1695 account, von Ziegler und Kliphausen[25] repeats Becherer's account, including the eating of the infants' hearts, lacking from Zeiller.[26]

- Christman Gnippertringa

In the 1606 continuation of Johannes Stumpf's "Schweytzer Chronick", it is noted that over a period of 30 years, a Christman Gnippertringa had killed a total of 964 people (no mention of cannibalism).[27]

- Christman Grepperunge

In this 1606 publication by Georg Nigrinus[28] and Martin Richter, it is noted that the woman made the decision to betray Grepperunge, in revenge for her dead children, the moment she managed to get free of him (no cannibalism noted).[29]

- The arch-cannibal is born

In this 1707 publication, Christian Gnipperdinga (or Gropperunge) is, for the first time credited with eating his victims in general, not only his own children. It is said that over a great area, he had hidden away his lair with great rocks, so that nobody would ever think anyone could live in that rock desert. In the city, the girl is promised by the authorities to receive a pension for life, if she betrays Gnipperdinga. It is further stated that she brought back from Bergkessel a bottle of extremely strong wine, and Gnipperdinga falls asleep, as planned, from drinking that wine.[30]

- "Murderers!", the cannibal screamed

Johann Joseph Pock, in his (1710) "Alvearium Curiosarum Scientiarum" furnishes basically a mixture of earlier accounts (including the eating of his infants' hearts), although he states that the young maiden wanted to visit friends in Trier, rather than her brothers. The most significant new element occurring in Pock is that with his dying breath, Christian Gnipperdinga screamed that he was murdered.[31]

- Christmann Gopperunge

In this publication from 1712 by Johann Gottfried Gregorii,[32] averring as its source is Becherer (1601), a strangely merciful execution is meted out, namely beheading, rather than being broken on the wheel.[33]

- Christian Gropperunge

Referring to a recent French case of a highwayman found guilty of 28 murders, the author of the 1731 "Schau-Spiegel europäischer Thaten oder Europäische Merckwürdigkeiten" offers a batch of similar cases, including that of Christian Gropperunge (without any of the exotic details already circulating, just the numbers and general locations)[34]

- A filthy, stinking cave

In his 1734 "Seraphisch Buß- und Lob-anstimmendes Wald-Lerchlein", Klemens Harderer basically follows the 1707 account, interspersing it with digressions of cannibals in general, and the sin of drinking wine. Adding to his source document, he says the cave was stinking from human flesh, filled with human bones, and the girl (here called Amarina) is force-fed human flesh herself.[35]

- A nameless cannibal's cave

In an oblique reference in this 1736 publication, the details of year, location and numbers are getting rather hazy, and what is remembered is that the cave contained lots of weapons, along with human bones and skulls.[36]

- Dorothea Teichner and Gnippordinga

By the nineteenth century, more polished fairy tales had developed in the Rhineland area about the terrible murderer who once roamed there. One of those tales is about the pious maiden Dorothea Teichner, who is unlucky enough to meet the murderer Gnippordinga. Much conversation is added relative to the original in Herber. She cannot understand how she can be his wife, because there is no priest present. Gnippordinga merely laughs, and says the green woods are priest good enough. Years go by, and even more infant skeletons fill up the branches of an old tree. And Dorothea weeps every time when the wind moves them clattering about, while Gnippordinga taunts her and says: "What are you whining about? Our children are dancing and playing, so stop crying!" One day, when he comes back severely wounded, he sends her off to Burgkastel, to fetch medicine. She breaks down in front of a statue of Mother Mary, and bemoans all the horrors she has endured. She is insensible of the people gathering around her, so she didn't consciously break her vows to Gnippodinga. Once he is lying on the wheel, his bones all broken and dangling from the wheel, his cries of pain when the wind moves them are met with the executioner's scornful words: "What are you whining about? Your bones are dancing and playing, so stop crying!"[37]

- Gniperdoliga, practitioner of the Black Arts

In none of the above given versions is there any mention of Genipperteinga making contracts with the devil, or having magical powers. However, the story of "Christman Gniperdoliga"/"Groperunge aus Kerpen" is also the basis of a "Moritat", or "Murderer's Ballad", typically performed at inns, fairs and markets. The content within that ballad, as retold by Kirschlager[38] do include such points as well, in that Gniperdoliga's cave was originally made by the dvarwes, and that he could make himself invisible by means of the Black Arts. In addition, the Moritat says Gniperdoliga was apprenticed under contemporary serial killer Peter Niers, having been his companion for 2 years. Finally, the Morität says that the booty from Gniperdoliga's was divided between a hospital and the poor, his erstwhile "mistress" receiving a share as well.

Alternate tales

A number of other fairy tales and folksongs are concerned, however, with the theme of the robber living in a cave shaped like a house, who kept a fair maiden captive, but who eventually escapes and betrays him. There are several alternate tales of Christman Genipperteinga, under alternate names, or have deviations from the original 1581 account.

Lippold and the Lippoldshöhle

About 2 km southwest of Brunkensen, now in the town Alfeld in Lower Saxony, lies a cave that at least from the mid-17th century has gone by the name Lippoldshöhle.[39] Writing in 1654, Martin Zeiller notes that there, "several hundred years ago", a robber named Lippold and his band had created their home, having made both a kitchen and stable there. Amongst other atrocities, they were rumoured to have kidnapped several young women, and strangled at birth the children they had with the women.[40] Another version of the tale identifies Lippold as a Count Lippold of Wrisberg, who at one point assaulted a wedded couple, killed the man and kidnapped the bride, and kept her as a slave for several years. At one point, she was allowed to go to Alfeld, bemoaned her fate at a stone at the council house, and this led eventually to Lippold's downfall.[41] According to yet another telling, the stone at the council house was originally red, but turned dark blue when she told the stone her harrowing tale. The stone is, reputedly, still there, and is depicted in the Alfeld's weapon shield. In this rendering, there was a hole in the roof of Lippold's cave, so that after he had fallen asleep in the maiden's lap while she was delousing him, the citizens let down a rope with a noose through the hole. The maiden fixed the noose around Lippold's neck, and he was strangled as the citizens pulled the rope up. Another version of his death is also given here, that the girl did not return at all, and that the citizens drowned Lippold by pouring water down the hole.[42]

Apart from the connotation of the Lippoldshöhle as having been the den of a terrible murderer, some have pointed out that in the 13th and 14th century, the cave lay in the territory of the Rössing family of nobles, many of them having as their first name Lippold.[43]

The robbers Danniel and Görtemicheel

Wolfgang Menzel (1858) furnishes a number of other folktales similar in content to the pamphlet concerning Christman Genipperteinga in his chapter "Fairy tales concerning the long suffering maidens".[44] The robber Danniel, whose brother was a smith and had helped him build his cave, was fond of abducting fair maidens. One of them had to live with him for seven years, but managed to flee, and was clever enough to distribute peas along the road, so that he was, eventually, caught. The robber Görtemicheel abducted a maiden, had seven children with her. She betrayed him on an errand to town, confessing her woes to a stone, and chose to mark the trail to the cave with peas. When returning, however, her tears suddenly flowed, and the robber understood that she betrayed him. As vengeance, he chose to decapitate their children, and hang the woman from a tree.

Schwarze Friedrich, Henning and Klemens

In 1661, the robber Schwarze Friedrich (Frederick the Black) met his fate close to Liegnitz, now Legnica. The elements of the murdered children and the song are lacking, but yet again, a maiden is held captive, marks the way to the robber's cave by peas, and confess her woes to a stone.[45]

The same basic scheme is found concerning the tales of robber Henning, whose reputed lair, the Henningshöhle,[46] close by Treffurt in Thuringia which until the 1960s could be visited, but is now collapsed.[47]

Close by the town Pritzwalk, the robber Klemens is to have had his lair and a captive maiden. She has also been extracted a vow never to betray him, but unbeknownst to her, when she bewails her fate to an oven, somebody who had hidden himself within it overheard her, and Klemens was caught.[48]

The robber Vieting

First attested in 1670 by Michael Cordesius,[49] a robber called Vieting is to have lived in the cave Vietingshöhle, in the Sonnenberg forest[50] near Parchim.

In order to alert himself whenever potential victims passed along the road through the forest, Vieting had devised a clever contraption with a thread, so that whenever anyone walked upon it, a small bell just outside his cave opening would ring. Then he could sneak up on the traveller and rob and murder them. One day, the bell rang once more, and Vieting brought his weapons with him, but when he saw the beautiful maiden Hanna walking along the road, singing to herself, he was smitten with desire, and chose, as Genipperteinga did, to order her to live with him as his mistress. Again, Vieting finally relented to let Hanna go to town to make some errands, after having sworn not to betray him. On her way back, she confessed her woes to a stone (and unbeknownst to her, several villagers listened in upon her), and in a distraught manner, some of the peas she had brought with her fell to the ground, thereby indicating for the villagers where they could find the murderer who had terrorized the region for so long. Vieting is caught and executed, and Hanna lives happily ever after, once again united with her family and friends.[51]

Papedöne

The robber Papedöne, who is to have lived in a cave called Papedöncken-Kuhl close to the village of Utecht[52] near Ratzeburg is also said, like Görtemicheel, to have revenged himself on their common children when he understood he had been betrayed by his woman. He killed their two sons, hung them up in a tree, and as the bodies moved with the wind, he sang:

So danzet, so danzet, my levesten Söhne, Dat danzen hat macket ju Vater Papedöne

So dance, so dance, my most beloved sons; your father Papedöne has made the dance for you[53]

In a version from 1738, Papedöncke kills his children at birth, just like Genipperteinga, has their heads fixed along the rope as he sings his verse.[54]

In another version of the Papedöne tale, he is said to have been active from 1314–1322. In this version, he used to hang the skulls of his murder victims from the branches of a tree, and used a rod to strike them to produce a melody, to which he sang the little song cited above. After having murdered six abducted maidens, he grew so fond of the seventh, that he couldn't bear killing her. Taking her once to the city of Lübeck, she recognized her brother in the crowd, but didn't speak out. Instead, she bought a bag of groats, and clandestinely marked the way back to Papedöne's lair, so that he eventually was caught.[55]

- A 1578 account concerning Papedöne

A work published in 1578, three years' prior to Genipperteinga's death, must hold particular interest. Here, the robber is fond of threading the skulls of his victims on a long rope, and banging them together, create the melody to which he liked to sing his ghastly rhyme. Here again, he kidnaps a young woman, who eventually betrays her secrets to a pier in a nearby church. The author of this work, Christoph Irenäus, says the story has previously been printed in the "Saxonian tongue".[56]

Lastly, the following quotation from Ranke (1978), concerning the Papedöne stories, is somewhat noteworthy relative to explaining Genipperteinga's name:[57]

"Vielleicht deuten auch lautverwandte Räubernamen auf Einflussnahme unserer Sage: der Knipper-"dähnke" der Oldenburger Fassung scheint mir ebenso wie der Peter "Dönges" (...) mit dem Pape "Döne" unserer Sage zusammenhängen"

"Possibly, it might be that robber names that has a similar ring to them suggests an influence from our myth: Pincers[58]-Dähnke from the Oldenburg tradition seems to me, as well as the Peter "Dönges" (...) tradition, to be related to the Pape "Döne" from our myth"

In one of these tales from Oldenburg, there is a whole robber band the poor maiden has to serve in their cave situated in the Damme Hills, she gets pregnant every year by them, but her babies are murdered at birth, and the robbers laugh and sing as the tiny bodies and skeletons sway in the wind:[59]

Knipperdoehnken, Knipperdoehnken, ei wat tanzt de jungen soehnken

See also

- Franz Schmidt, contemporary executioner for 45 years in Bamberg and Nuremberg, who left a diary detailing his work as executioner. He executed a total of 361 individuals during his career

- Sawney Bean, a possibly fictional Scottish bandit and cannibal

References

Bibliography

- Archiv für Landeskunde (1859). Archiv für Landeskunde in den Grossherzogthümen Mecklenburg und Revüe der Landwirtschaft, Jahrgang 9. Schwerin: A.W. Sandmeyer. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Bartsch, Karl (2012). Sagen und Märchen aus Mecklenburg. Jazzybee Verlag. ISBN 9783849602871. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Becherer, Johann (1601). Newe Thüringische Chronica. Mülhausen: Johann Spiess. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Breslau, Ralf (1997). Der Nachlass der Brüder Grimm: Teil 1. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447038577. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Burghart, Gottfried H. (1736). Gothofr. Henr. Burgharti ... Iter sabothicum, das ist, Ausführliche Beschreibung einiger an. 1733 und die folgenden Jahre auf den Zothen-Berg gethanen Reisen: wodurch sowohl die natürliche als historische Beschaffenheit dieses in Schlesien so bekannten und berühmten Berges der Welt vor Augen geleget wird. Breslau, Leipzig: Michael Hubert. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Deecke, Ernst (1857). Lübische Geschichten und Sagen. Lübeck: Dittmer'sche Buchhandlung. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Flora (1820). Flora: Ein Unterhaltungs-Blatt. Munich. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Freund, Marcus (1658). Zeit-und Wunder-Calender auff das Jahr 1658.

- Gregorii, Johann G. (1712). kuriose und gelehrte Historicus. Frankfurt and Leipzig: J. C. Stössel. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Grässe, Johann G.T. (1868). Sagenbuch des preussischen Staats. 2 Bd, Volume 1. Glogau: Carl Flemming. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Grässe, Johann G.T. (1871). Sagenbuch des preussischen Staats. 2 Bd, Volume 2. Glogau: Carl Flemming. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Harderer, Klemens (1734). Seraphisch Buß- und Lob-anstimmendes Wald-Lerchlein, Das ist: Hundert Sonn- und Feyertags-Predigen an sowohl hoh- als niedere Stands-Persohnen, Stadt- und Dorffs-Leuth, volume 2. Augsburg: Veith, Gastel. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Herber, Caspar (1581). Erschröckliche newe Zeytung Von einem Mörder Christman genant, welcher ist Gericht worden zu Bergkessel den 17. Juny diß 1581 Jars. Mainz: Caspar Herber. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Hondorf, Andreas; Rivander, Zacharias (1581). Promptuarium Exemplorum: Darinnen viel Herrliche Schöne Historien Allerley alten vnd neuwen Exempel, Auch viel nützliche, merckliche vnd denckwirdige Geschichten, von Tugendt vnd Untugendt... Verfasset sind.... ¬Der ander Theil, Volume 2. Frankfurt am Main: Feyerabendt und Spieß. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Hondorff, Andreas; Sturm, Vincenz (1587). Calendarium Sanctorum et historiarum. Frankfurt am Main: Nicholaus Basseus. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Hondorff, Andreas; Sturm, Vincenz (1599). Calendarium Sanctorum et historiarum. Leipzig: Henning Gross. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Janssen, Johannes; Christie, A.M. (tr.) (1907). History of the German people at the close of the Middle Ages, Volume 12. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner&Co, Ltd. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Kessens, Bernd (2004). Die Räuber vom Mordkuhlenberg. Taurino. ISBN 978-3980580090.

- Kirchschlager, Michael (2007). Menschliche Ungeheuer vom späten Mittelalter bis zum Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts (Historische Serienmörder. Bd. 1 = Bibliothek des Grauens Bd.6). Arnstadt: Kirchschlager. ISBN 978-3-934277-13-7.

- Klüver, Hans H. (1738). Beschreibung des Hertzogthums Mechlenburg und dazu gehöriger Ländar und Örter erster[-sechster] Theil ...:vormahls zusammen getragen von Hans Henrich Klüver, Volum 2. Hamburg: Thomas von Wieringe Erben. Retrieved 2013-02-02.

- Kuhn, Adalbert; Schwartz, Wilhelm (1848). Norddeutsche Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche aus Meklenburg, Pommern, der Mark, Sachsen, Thüringen, Braunschweig, Hannover, Oldenburg und Westfalen. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Lübbing, Hermann (1968). Oldenburgische Sagen. Holzberg. ASIN B002MSCI2Q. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Samuel Meiger (1649). Nucleus historiarum.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Menzel, Wolfgang (1858). Deutsche Dichtung von der ältesten bis auf die neueste Zeit: in 3 Bd, Volume 1. Stuttgart: Adolph Krabbe. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Merian, Matthaeus; Zeiller, Martin (1654). Topographia und Eigentliche Beschreibung Der Vornembsten Stäte, Schlösser auch anderer Plätze und Örter in denen Hertzogthümer[n] Braunschweig und Lüneburg, und denen dazu gehörende[n] Grafschafften Herrschafften und Landen. Merian. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Niederhöffer, Albert (1858). Mecklenburg's Volkssagen, Volume 1. Leipzig: Heinrich Hübner. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Nigrinus, Georg; Richter, Martin (1710). Historiarum MeDVLLa Das ist: Beschreibung aller vornembsten Hauptverenderungen... Biß auff diese gegenwertige Zeit. Frankfurt am Main: Johan Jacob Porschitz. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Palla, Rudi (1994). Verschwundene Arbeit.:Ein Thesaurus der untergegangenen Berufe. Eichborn Verlag Ag. ISBN 9783821844435. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Pock, Johann J. (1710). Alvearium Curiosarum Scientiarum, Oder Immen-Hauß Verwunderlicher Wissenschafften. Augsburg: Schlüter, Happach. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Ranke, Kurt (1954). "Die Sage vom Räuber Pape Dön" in "NORDELBINGEN. 22. Band. Beiträge zur Heimatforschung in Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg und Lübeck". Heide, Holstein: Boyens.

- Ranke, Kurt (1978). Die Welt der einfachen Formen. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110074208. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Rehermann, Ernst H. (1977). Schriften zur Niederdeutschen Volkskunde, Volume 8. O. Schwartz. ISBN 9783509005592. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Rölleke, Heinz (1981). Westfälische Sagen. Diederichs. ISBN 9783424007039. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Schambach, Georg; Müller, Wilhelm (1948). Niedersächsische Sagen und Märchen. Jazzybee Verlag. ISBN 9783849603168. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Schanz, Julius; Kauffer, Eduard (1855). Die schönsten deutschen Sagen, Volksmärchen u. Legenden in Poesie und Prosa. Dresden: J. Breyer. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Scheible, Johann (1847). Das Schaltjahr; welches ist der teutsch Kalender mit den Figuren, und hat 366 Tag, Volume 5. Stuttgart: Johann Scheible. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Schlüter, Happach (1707). Politische Conferentz zwölff unterschiedlicher Stands-Persohnen von allen neuen vorfallenden Friedens- und Kriegs-Begebenheiten der gantzen Welt. Augsburg: Schlüter, Happach. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Schultz, Alwin (2011). Das häusliche Leben der europäischen Kulturvölker vom Mittelalter bis zur zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts (reprint from 1903). Bremen: Outlook verlagsgesellschaft mbH. ISBN 9783864031977. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Sperber, Julius (1660). Von den dreyen Seculis oder Haupt-zeiten, von Anfang biss zum Ende der Welt. Amsterdam: B. Bahnsen. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Stieffler, Johann (1668). Loci Theologiae Historici, Das ist: Geistlicher Historien-Schatz. Breslau, Jena: Johann Nisius.

- Ludwig Strackerjan (1867). Aberglaube und Sagen aus dem Herzogthum Oldenburg. G. Stelling.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stumpf, Johannes; Stumpf, Johann R. (1606). Schweytzer Chronick: Das ist, Beschreybung gemeiner löbicher Eydgnoschafft. J. Wolff. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Sturm, Augustus (1731). Schau-Spiegel europäischer Thaten oder Europäische Merckwürdigkeiten. Augsburg: Augustus Sturm. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Volkmar, Manfred (2011). Sagenhaftes entlang der Werra zwischen Eisfeld und Treffurt. Erfurt: Sutton Verlag GmbH. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- von Wedel, Andreas (1882). Hausbuch des Herrn Joachim von Wedel auf Krempzow Schloss und Blumberg erbgesessen. Tübingen: Litterarischer Verein in Stuttgart. OL 16989793M.

- Christian Weidling (1700). Der Gelehrte Kirchen-Redner, oder Excerpta Homiletica, welche aus des Seel. Herrn Lutheri, der vornehmsten Kirchen-Väter und vortrefflichsten Theologorum, als Chemnitii, Gerhardi, Dannhaueri, Balduini, Welleri, Botsacci, Finckii, Brochmanni, Hermanni, Dieterici etc. und vieler andern Schrifften mehr, einen reichen Vorrath sehr gelehrter Realien ... nach der erbaulichen Methode, welche der Sel. D. König in seiner Theologia Positiva beliebet, præsentiren, auff wiederhohltes Verlangen so wohl Geistlichen als Politischen Rednern zu gelehrter Erbauung Communiciret von D. Christian Weidlingen ...CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiltenburg, Joy (2012). Crime and Culture in Early Modern Germany. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 9780813933023. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Zeiller, Martin (1640). Ein Hundert Episteln, oder Sendschreiben, Von vnderschidlichen Politischen, Historischen, vnd andern Materien, vnd Sachen. Ulm: Görlin. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Zeiller, Martin (1661). Miscellanea. Nuremberg: Georg Wild Eisen. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Zeitschrift des Historischen Vereins (1860). Zeitschrift des Historischen Vereins für Niedersachsen, Jahrgang 1859. Hannover: Hahn'schen Hofbuchhandlung. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- von Ziegler und Kliphausen, Heinrich (1695). Heinrich Anshelms von Ziegler und Kliphausen, ... Täglicher Schau-Platz der Zeit: auff welchem sich ein iedweder Tag durch das gantze Jahr mit seinen merckwürdigsten Begebenheiten, so sich von Anfange der Welt biss auff diese ietzige Zeiten, an demselben zugetragen vorstellig mache. Leipsig: Gleditsch. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

Notes

- Herber, p. 1–2.

- Wiltenburg ch 1, 2012

- Hondorff, Sturm (1587), p.333–34

- Kirschslager, 2007

- Herber, page 2

- For a batch of such cases, see, for example Schultz (2011), p.397-398

- Herber, page 3

- Herber, page 4

- Herber, p. 3–4.

- Scheible, 1847

- Herber, page 5

- Herber, page 6

- Heber, page 1

- Wiltenburg Intr, 2012

- Janssen, Christie (1907), p.271

- Janssen, Christie (1907), p.273

- Janssen, Christie (1907), p.274

- Hondorff, Sturm (1587), p.333–34 or Hondorff, Sturm (1599), p.471–72

- de:Joachim von Wedel

- von Wedel, p.283

- de:Julius Sperber

- Sperber (1660), p.163

- Becherer (1601) p.590-91

- Zeiller (1661), p.303 In an earlier, 1640 work Martin Zeiller notes the existence of a small pamphlet concerning an unnamed murderer at an unnamed place who killed 964 persons, erronously dating this to 1580, Zeiller (1640), p.232

- de:Heinrich Anselm von Ziegler und Kliphausen

- von Ziegler und Kliphausen (1695), p.713

- Stumpf (1606), p. cxxxi

- "Georg Nigrinus" (in German). De.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- Nigrinus, Richter (1606), p.62

- (1707)p.89–92

- Pock (1710), p.338–39

- "J.G. Gregorii". Bach-in-dornheim.de. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- Gregorii (1712), p.551

- Sturm (1731), p.63

- Harderer (1734), p.32–39

- Burghart (1736), p.90

- Schanz (1855), p.94 A roughly similar version is contained in Flora (1820), p.303 Furthermore, in the leftover material from the Brothers Grimm, the tale of the Räuber Gnipperdinga seems to be included, Breslau (1997), p.596

- Execerpt at Kirschlager

- de:Lippoldshöhle

- Merian, Zeiller (1654), p.61

- Schambach, Müller (1948), p.69-71

- Kuhn, Schwartz (1848), p. 249–250

- Zeitschrift Hist. Verein Niedersachsen (1860), p. 196–197

- This entire paragraph is based on Menzel (1858), p.149–160

- Grässe (1871), p.192

- de:Henningshöhle

- A Henning-tale can be found in Volkmar (2011), p.90–91

- Grässe (1868), p.103

- For Cordesius, see for example Archiv für Landeskunde (1859), p.427

- Sonnenberg Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine and Räuber Vieting

- Niederhöffer (1858), p.100

- On Utecht and cave name,Klüver (1738), p.293

- Menzel (1858), p.149-160

- Klüver (1738), p.293

- Deecke (1857), p.99 See also the 2012 edition of Karl Bartsch's 1879-work, Bartsch (2012), p.617–618

- Irenäus work (1578) work is briefly quoted in Rehermann (1977), p.500; a 1581 re-telling of Irenäus is found in the 1581 account Hondorf, Rivander (1581), p.249-250

- Ranke (1978), p.131

- Knipper is someone working with a set of pincers ("Knippe"/"Kniepe"), and is attested in use for artisans such as cobblers, leatherworkers and ironworkers. See, for example, Palla (1994), p.400

- Lübbing (1968), p.263 The full tale can be read at Die Sage vom Mordkuhlenberg Ranke (1978), cites, at p.126, the rendition Knipperdähnken, a version to be found in Strackerjan (1867), p.215–216 This is also the form used in Rölleke (1981), p.139 A modern retelling of the story can be found in Bernd Kessens' (2004) audiobook "Die Räuber vom Mordkuhlenberg"