Chobe National Park

Chobe National Park is Botswana's first national park, and also the most biologically diverse. Located in the north of the country, it is Botswana's third largest park, after Central Kalahari Game Reserve and Gemsbok National Park, and has one of the greatest concentrations of game in all of Africa.

| Chobe National Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

Wildebeest and zebras in Chobe National Park | |

| |

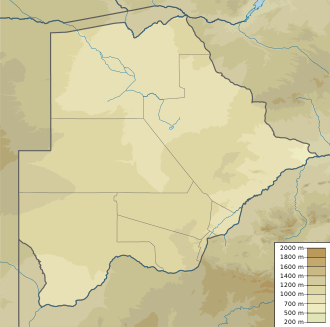

| Location | Botswana |

| Nearest city | Kasane |

| Coordinates | 18°40′S 24°30′E |

| Area | 11,700 km2 (4,500 sq mi) |

| Established | 1967 |

This park is noted for having a population of lions which prey on elephants, mostly calves or juveniles, but even subadults[1]

History

The original inhabitants of this area were the San bushmen (also known as the Basarwa people in Botswana). They were nomadic hunter-gatherers who were constantly moving from place to place to find food sources, namely fruits, water and wild animals. Nowadays one can find San paintings inside rocky hills of the park.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the region that would become Botswana was divided into different land tenure systems. At that time, a major part of the park's area was classified as crown land. The idea of a national park to protect the varied wildlife found here as well as promote tourism first appeared in 1931. The following year, 24,000 km2 (9,300 sq mi) around Chobe district were officially declared non-hunting area; this area was expanded to 31,600 km2 (12,200 sq mi) two years later.

In 1943, heavy tsetse infestations occurred throughout the region, delaying the creation of the national park. By 1953, the project received governmental attention again: 21,000 km2 (8,100 sq mi) were suggested to become a game reserve. Chobe Game Reserve was officially created in 1960, though smaller than initially desired. In 1967, the reserve was declared a national park.

At that time there were several industrial settlements in the region, especially at Serondela, where the timber industry proliferated. These settlements were gradually moved out of the park, and it was not until 1975 that the whole protected area was exempt from human activity. Nowadays traces of the prior timber industry are still visible at Serondela. Minor expansions of the park took place in 1980 and 1987.

Geography and ecosystems

The park can be divided up to 4 areas, each corresponding to one distinct ecosystem:

- The Serondela area (or Chobe riverfront), situated in the extreme Northeast of the park, has as its main geographical features lush floodplains and dense woodland of mahogany, teak and other hardwoods now largely reduced by heavy elephant pressure. The Chobe River, which flows along the Northeast border of the park, is a major watering spot, especially in the dry season (May through October) for large breeding herds of elephants, as well as families of giraffe, sable and cape Cape buffalo. The flood plains are the only place in Botswana where the puku antelope can be seen. Birding is also available. Large numbers of carmine bee eaters are spotted in season. When in flood spoonbills, ibis, various species of storks, ducks and other waterfowl flock to the area. This is likely Chobe's most visited section, in large part because of its proximity to the Victoria Falls. The town of Kasane, situated just downstream, is the most important town of the region and serves as the northern entrance to the park.

- The Savuti Marsh area, 10,878 km2 (4,200 sq mi) large, constitutes the western stretch of the park (50 km (31 mi) north of Mababe Gate). The Savuti Marsh is the relic of a large inland lake whose water supply was cut a long time ago by tectonic movements. Nowadays the marsh is fed by the erratic Savuti Channel, which dries up for long periods then curiously flows again, a consequence of tectonic activity in the area. It is currently flowing again and in January 2010 reached Savuti Marsh for the first time since 1982. As a result of this variable flow, there are hundred of dead trees along the channel's bank. The region is also covered with extensive savannahs and rolling grasslands, which makes wildlife particularly dynamic in this section of the park. During dry seasons, tourists going on a safari often sight rhinoceros (both black and white), warthog, kudu, impala, zebra, wildebeest and a herd of elephants. During rain seasons, the rich birdlife of the park, 450 species in the whole park, is well represented. Prides of lions, hyenas, zebras or more rarely cheetahs are sighted as well. This region is reputed for its annual migration of zebras and predators.

- The Linyanti Marsh, located at the northwest corner of the park and to the north of Savuti, is adjacent to the Linyanti River. To the west of this area lies Selinda Reserve and on the northern bank of Kwando River is Namibia's Nkasa Rupara National Park. Around these two rivers are riverine woodlands, open woodlands as well as lagoons, and the rest of the region mainly consists of flood plains. There are large concentrations of lion prides, leopard, African wild dog, roan antelope, sable antelope, a hippopotamus pod and herds of African bush elephant. The rarer red lechwe, sitatunga and a bask of Nile crocodiles also occur in the area. Bird diversity is rich.

- Between Linyanti and Savuti Marshes lies a hot and dry hinterland, mainly occupied by the Nogatsaa grass woodland. This section is little known and is a great place for spotting elands.

_deborando_un_b%C3%BAfalo_africano_negro_(Syncerus_caffer_caffer)%2C_parque_nacional_de_Chobe%2C_Botsuana%2C_2018-07-28%2C_DD_94-96_PAN.jpg) Lions devouring their killing

Lions devouring their killing%2C_parque_nacional_de_Chobe%2C_Botsuana%2C_2018-07-28%2C_DD_79.jpg)

Jackal pup

Jackal pup Southern African cheetah

Southern African cheetah%2C_parque_nacional_de_Chobe%2C_Botsuana%2C_2018-07-28%2C_DD_32.jpg) Common warthogs (Phacochoerus africanus) in the banks of the Chobe River.

Common warthogs (Phacochoerus africanus) in the banks of the Chobe River.

Elephant concentration

The park is widely known for its large elephant population, estimated to be around 50,000. Elephants living here are Kalahari elephants, the largest in size of all known elephant populations. They are characterized by rather brittle ivory and short tusks, perhaps due to calcium deficiency in the soils. Damage caused by the high numbers of elephants is rife in some areas. In fact,[2] concentration is so high throughout Chobe that culls have been considered, but are too controversial and have thus far been rejected. At dry season, these elephants sojourn in Chobe River and the Linyanti River areas. In the rainy season, they make a 200-kilometre migration to the south-eastern stretch of the park. Their distribution zone however outreaches the park and spreads to north-western Zimbabwe.

Roads

Road conditions in Chobe National Park depend greatly on the season and rainfall and one would need a 4x4 vehicle to travel in the Park. Thick sand becomes a problem in the Chobe River Front during the dry months, particularly as the temperature rises and during the wet season the roads near the river become muddy.[3]

Savuti

Savuti roads, mainly the western Sandridge Road from Mababe Gate and the roads both north and south of the Savuti channel are typically thick sand and tricky to drive. When rain has fallen, driving along the marsh roads, as the wet black cotton soil becomes unnavigable, carries the risk of getting stuck.[3]

Nogatsaa

Nogatsaa roads are waterlogged during the wet months and very little of the road network can be driven at this time. During the dry months, game drives from one pan to the next are on roads with small, thick sandy patches. Once leaving the tar road from Kasane, people would have to drive through thick sand for the first 20 km (12 mi), before reaching a sand road.[3]

See also

References

- Power, R. J.; Compion, R. X. Shem (2009). "Lion predation on elephants in the Savuti, Chobe National Park, Botswana". African Zoology. 44 (1): 36–44. doi:10.3377/004.044.0104.

- "Elephant culls in Chobe". Archived from the original on 2008-01-11. Retrieved 2006-06-13.

- "Chobe National Park, October 2017". Independent Travellers. independent-travellers.com. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chobe National Park. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chobe_National_Park. |