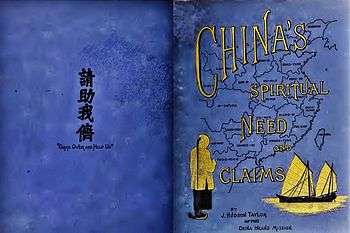

China's Spiritual Need and Claims

China’s Spiritual Need and Claims (original title: China: Its Spiritual Need and Claims)[1] is a book written by James Hudson Taylor, the founder of the China Inland Mission, in October 1865. It is arguably the most significant work regarding Christian missions to China in the 19th century. A manifesto of Taylor’s life and work, it describes in stark detail the desperate lack of Protestant Christian missionary endeavor among the people of China. The book was reprinted several times over thirty years and motivated uncounted numbers of Christians in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand to volunteer for service in east Asia. China’s Spiritual Need and Claims helped foster the widest evangelistic campaign since the time of Paul the Apostle. Charles Spurgeon noted in 1879:

The word China, China, China is now ringing in our ears in that special, peculiar, musical, forcible, unique way in which Mr. Taylor utters it.[2]

China's millions

China’s Spiritual Need and Claims was a prime recruitment tool for the newly begun China Inland Mission, but it also influenced men and women to apply for service with other mission agencies. Taylor compiled the book at the urging of his pastor, William Garrett Lewis, of Westbourne Grove Church, who thought that the topic was too weighty not to be printed.

Taylor's wife, Maria, helped him in the writing of the book. On Sundays, they worked together, and she mostly transcribed his words. They were both influenced by a book by Evan Davies (missionary) called China and her Spiritual Claims from about twenty years previously.

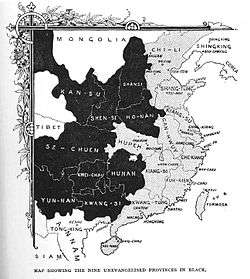

Taylor began by affirming the biblical teachings that all men are lost without Christ, that the Gospel is for all, and that the Great Commission specifies that the church is to “make disciples” of all peoples. He then identified those in China who had yet to hear the Gospel and believe in Jesus Christ. Indeed, Taylor's research uncovered

...the startling fact that even in the seven provinces in which such work had begun there were still a hundred and eighty-five millions utterly and hopelessly beyond the reach of the gospel....And beyond these again lay the eleven inland provinces - two hundred millions more without a single witness for Christ[3]

.

Taylor emphasized this “by comparisons and diagrams.” These statistics were profoundly real to him:

A million a month in China are dying without God, and we who have received in trust the Word of Life — we are responsible[4]...Four hundred millions! What mind can grasp it? Marching in single file one yard apart they would circle the world at its equator more than ten times. Were they to march past the reader, at a rate of thirty miles a day, they would move on and on, day after day, week after week, month after month; and more than twenty-three years and a half would elapse before the last individual had passed by…Four hundred millions of souls, ‘having no hope, and without God in the world’…an army whose forces, if placed singly, father more than four hundred yards apart and within call of each other would extend from the earth to the sun! who, standing hand in hand, might extend over a greater distance than from this globe to the moon! The number is inconceivable – the view is appalling.[5]

In this book the whole field of missionary work in China was carefully surveyed, and it was shown that in the seven provinces in which Protestant missionaries had already been working, there were 204 million people, with only 91 workers, but there were eleven other provinces in inland China, with a population estimated at 197 million, for whom absolutely nothing had been attempted. After having carefully set forth and tabulated these facts and figures, the needs of the outlying dependencies of China were also recounted. The book was no mere dry summary of statistics. The heart of the writer was felt on every page. The needs, the possibilities, the facilities for work were all set forth in reasoned argument. The country was accessible, for the Treaty of Tientsin in 1858, ratified at Beijing in 1860, had, in Articles VIII., IX., and XII., promised religious liberty, authorized British subjects to travel inland, and permitted the building of churches and hospitals. Roman Catholic missionaries were already living and working in the interior. The contrast between the efforts of the Roman and Protestant Churches was fully set forth as a reproach to all Protestants in later editions of the book.

We refer the reader to the deeply important paper appended to the preface to this (the third) edition the comparative table of statistics of Roman Catholic and Protestant Missions in China in 1866 which will prove most suggestive to the thoughtful mind. How is it that 286 Roman Catholic missionaries, with but few exceptions, not only can live but are actually residing in the interior, are labouring in each of the eighteen provinces (and in the outlying regions), and are spread over the whole extent of these provinces ; while the 112 Protestant missionaries, with still fewer exceptions, are congregated together in the few free Ports of commerce ? [6]

A first edition of three thousand copies of this appeal was published in October 1865 through the generous help of Mr. William Thomas Berger, and copies were by permission freely distributed at the Mildmay Conference, held that year, which at that time was held in the last week of October. Another edition was called for in the following year, and another in 1868, and again another in 1872, and then for a time the book was allowed to go out of print. But between June 1884 and September of the same year a fifth edition of five thousand copies was exhausted, and a sixth and seventh edition followed soon after.[7]

Soon, churches on both sides of the Atlantic were influenced by the book. Many new missionary societies were formed and hundreds of workers were recruited, largely from the thousands of university students influenced by the ministry of D. L. Moody.

Among those who were influenced to go and to serve in China because they had read this book were the Lammermuir Party, Jonathan Goforth, and many missionaries with the China Inland Mission

References

- Taylor, James Hudson (1865). China: Its Spiritual Need and Claims. London: James Nisbet.

- Taylor, James Hudson (1868). China's Spiritual Need and Claims (Third Edition). London: James Nisbet.

- Broomhall, Marshall (1915). The Jubilee Story of the China Inland Mission. London: Morgan and Scott.

- Spurgeon, Charles (1879). Sword and Trowel. London: Passmore and Alabaster.

- Taylor, Dr. and Mrs. Howard (1918). Hudson Taylor and the China Inland Mission; The Growth of a Work of God. London: Morgan and Scott.

Notes

- James Hudson Taylor (1865). China; its spiritual need and claims; with brief notices of missionary effort, past and present. James Nisbet.

- Spurgeon (1879), Interviews with Three of the King's Captains

- Taylor (1918), p. 39

- Taylor (1918), p. 24

- Taylor (1865)

- Taylor (1868)

- Broomhall (1915), 27-28

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Historical Bibliography of the China Inland Mission