Cheyenne River Indian Reservation

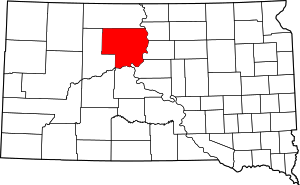

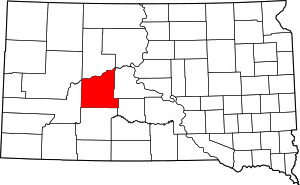

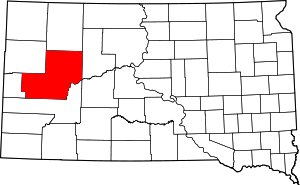

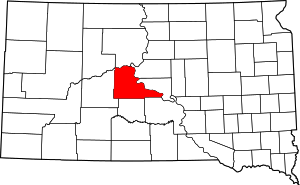

The Cheyenne River Indian Reservation was created by the United States in 1889 by breaking up the Great Sioux Reservation, following the attrition of the Lakota in a series of wars in the 1870s. The reservation covers almost all of Dewey and Ziebach counties in South Dakota. In addition, many small parcels of off-reservation trust land are located in Stanley, Haakon, and Meade counties.

Cheyenne River Indian Reservation | |

|---|---|

Farmland on the reservation | |

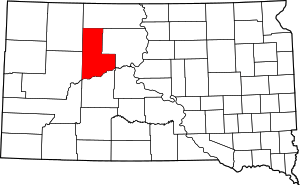

Location in South Dakota | |

| Coordinates: 45°04′35″N 101°13′33″W | |

| Tribe | Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe |

| Country | United States |

| State | South Dakota |

| Counties | Dewey Haakon Meade Stanley Ziebach |

| Established | 1889 |

| Government | |

| • Governing body | General Tribal Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11,051.447 km2 (4,266.987 sq mi) |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • Total | 8,090 |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-6 (MDT) |

| Website | sioux.org |

The total land area is 4,266.987 sq mi (11,051.447 km²), making it the fourth-largest Indian reservation in land area in the United States. Its largest community is unincorporated North Eagle Butte, while adjacent Eagle Butte is its largest incorporated city.

Land Status

The original Cheyenne River Reservation covered over 5,000 sq. mi. The Reservation has subsequently decreased in size; today it is 4,266.987 sq mi (11,051.447 km²). The original northern boundary was the Grand River. However, in the early 20th century, land south of the Grand River was ceded to the Standing Rock Reservation. The land was opened up to non-Native settlement 1909. When the Land Acts took effect, the northern part of the Cheyenne River Reservation was lost. However, the southern section of the Cheyenne River Reservation still remains. It covers 1,514,652 acres or 2,366 sq. mi.

A small number of White River Utes were resettled on the Reservation in 1906 and 1907, being allocated 4 townships totalling 92,160 acres.[2] That land remains in the former northern part of the Cheyenne River Reservation. Their communities are Iron Lightning and Thunder Butte.

Four Bear Creek, tributary of the Missouri River, is located in the Cheyenne River Reservation.[3]

History

The Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 created the Great Sioux Reservation, a single reservation covering parts of six states, including both of the Dakotas. Subsequent treaties in the 1870s and 1880s broke this reservation up into several smaller reservations. The Cheyenne River Indian Reservation was created in 1889.[4]

Chief Sitting Bull lived on the Cheyenne River Reservation. He was fond of the Grand River area, which in the 1880s was the boundary between the Cheyenne River Reservation and the Standing Rock Reservation. In 1890, the United States became very concerned about Chief Sitting Bull who they learned was going to lead an exodus off the Reservation.

Several hundred Indians gathered near the Grand River on the Cheyenne River Reservation in December 1890, preparing to flee the reservation. A force of 39 Indian policemen and four volunteers were sent to chief Sitting Bull's residence near the Grand River on December 16, 1890, to arrest him.

Initially, Sitting Bull cooperated but became angry once led out of his residence and noticed around 50 of his soldiers were there to support him. During some point while outside of chief Sitting Bulls residence, a battle commenced in which the legendary leader was killed. A total of 18 casualties occurred in the battle. Among the killed were Sitting Bull and his son.

Sitting Bull's half brother, Spotted Elk, led an exodus of 350 people off the Cheyenne River Reservation to the south. They were captured on December 28, 1890 on the Pine Ridge Reservation, about 30 miles to the east of the settlement of Pine Ridge. Next day they were attacked by over 500 US Army soldiers, and event known as the Wounded Knee Massacre. Approximately 250 to 300 Natives were killed, including many women and children, and the massacre halted the exodus.[5] Survivors settled on the Pine Ridge Reservation or returned to the Cheyenne River Reservation.

Since then, the Cheyenne River Reservation's northern border has changed. It is no longer the Grand River. The 60th United States Congress authorized the sale of unallotted land on the reservation in 1908, and in 1909 William Howard Taft issued a presidential proclamation which opened up the Cheyenne River Reservation to white settlement.[6]:13 However, the present day settlements located along the Grand River are predominantly Algonquian.

Beginning in 1948, the US government dammed the Missouri River for electrical power and flood control. The dam project submerged 8% of reservation land.[4]

On August 15, 2018, at 9:06 a.m. MDT, the tribe signed KIPI on the air. The station will serve as an educational and economic opportunity for residents of the reservation.

Current conditions

The CRIR is the home of the federally recognized Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe (CRST) or Cheyenne River Lakota Nation (Oyate). The members include representatives from four of the traditional seven bands of the Lakota, also known as Teton Sioux: the Minnecoujou, Two Kettle (Oohenunpa), Sans Arc (Itazipco) and Blackfoot (Sihásapa).

The CRIR is bordered on the north by the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, on the west by Meade and Perkins Counties; on the south by the Cheyenne River; and on the east by the Missouri River in Lake Oahe. Much of the land inside the boundaries is privately owned. The CRST headquarters and BIA agency are located at Eagle Butte, South Dakota. The reservation is reached via US-212.

The 2010 census reported a population of 8,090 persons.[1] Many of the 13 small communities on the Cheyenne River Reservation do not have water systems, making it difficult for people to live in sanitary conditions. In recent years, water systems have been constructed that tap the Missouri Main Stem reservoirs, such as Lake Oahe, which forms the eastern edge of the Reservation.

With few jobs available on the reservation or in nearby towns, many tribal members are unemployed. Two-thirds of the population survives on much less than one-third of the American average income. Such dismal living conditions have contributed to feelings of hopelessness and despair among the youth. Indian Country Today reports than one in five girls on the Cheyenne River Reservation has contemplated suicide and more than one in ten has attempted it. As of 2009, a modern medical center was under construction in Eagle Butte to replace an outdated facility.[7]

Beginning on January 22, 2010, a blizzard and ice storm swept across the reservation, downing as many as 3,000 power lines and leaving thousands of residents without power, heat or water. Response to the disaster was slow. Although the state government declared a state of emergency, the situation did not initially receive much attention in the media or from legislators. Power was finally restored to most residents as of February 12, 2010, but overall conditions were still grim.

On February 14, 2010, the TV commentator Keith Olbermann highlighted the situation on his program Countdown with Keith Olbermann. Within 48 hours more than $250,000 in donations was raised for the reservation. As of February 24, 2010, more than $400,000 in donations had been raised. No deaths had been reported as a result of the disaster. Several elderly residents dependent on dialysis treatment were evacuated to nearby towns. As of February 26, 2010, tribal representatives are turning attention to raising awareness about the reservation's damaged water infrastructure.[8][9][10]

Communities

The communities of Iron Lightning, Thunder Butte, Bullhead, Little Eagle, and Wakpala date back to the original 1889 reservation boundaries. Nearly all communities on the Cheyenne River Reservation, including in the land area settled by white homesteaders after 1908, have a majority population of Native Americans. Most of the communities rank as the lowest income per-capita in the United States. However, Eagle Butte and North Eagle Butte are more economically diverse, and main business district of Eagle Butte is similar to that of many communities of with comparable populations.

- Blackfoot

- Bridger

- Dupree

- Cherry Creek

- Green Grass

- Iron Lightning

- Isabel

- La Plant

- North Bridger

- North Eagle Butte

- Red Scaffold

- Swiftbird

- Thunder Butte

- Timber Lake

- Whitehorse

- Bear Creek, South Dakota

Notable tribal members

- Madonna Swan, Lakota author from Cheyenne River Indian Reservation

References

- "2010 Census Summary File 1: Cheyenne River Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, SD". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Laudenschlager, David D. (Summer 1979). "The Utes in South Dakota, 1906-1908" (PDF). South Dakota History. 9 (3): 233–247. ISSN 0361-8676. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Sportsman's Connection (2016). South Dakota Fishing Maps Guide Book. Superior, Wisconsin: Billing, Jim. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-885010-61-2.

- "South Dakota: Cheyenne River Reservation". nativepartnership.org. Addison, TX: Partnership With Native Americans. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Nelson A. Miles to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, March 13, 1917, "The official reports make the number killed 90 warriors and approximately 200 women and children."

- Hoxie, Frederick E. (Winter 1979). "From Prison to Homeland: The Cheyenne River Indian Reservation before WWI" (PDF). South Dakota History. 10 (1): 1–24. ISSN 0361-8676. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Dan Barry, "A Rising but Doubted Dream on a Reservation", The New York Times, 12 July 2009

- John R. Platt, " Keith Olbermann Helps Raise $250,000 for Storm-Ravaged Cheyenne River Reservation" Archived February 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Tonic, 15 February 2010

- "Help for Storm-Battered Sioux Tribe", MSNBC, 24 February 2010

- "Many on South Dakota Reservation Remain Without Power After Storm", The New York Times, 31 January 2010

External links

![]()