Pseudoscorpion

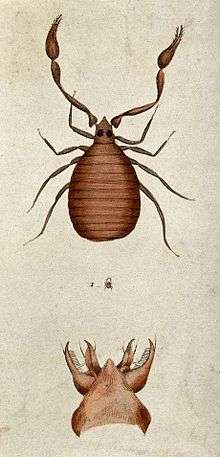

A pseudoscorpion, also known as a false scorpion or book scorpion, is an arachnid belonging to the order Pseudoscorpiones, also known as Pseudoscorpionida or Chelonethida.

| Pseudoscorpions (false scorpion) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Pseudoscorpiones Haeckel, 1866 |

| Superfamilies | |

Pseudoscorpions are generally beneficial to humans since they prey on clothes moth larvae, carpet beetle larvae, booklice, ants, mites, and small flies. They are tiny, and are rarely noticed due to their small size, despite being common in many environments. When people do see pseudoscorpions, especially indoors, they are often mistaken for ticks or small spiders. Pseudoscorpions often carry out phoresy, a form of commensalism in which one organism uses another for the purpose of transport.

Characteristics

Pseudoscorpions belong to the class Arachnida.[1] They are small arachnids with a flat, pear-shaped body, and pincer-like pedipalps that resemble those of scorpions. They usually range from 2 to 8 millimetres (0.08 to 0.31 in) in length.[2] The largest known species is Garypus titanius of Ascension Island[3] at up to 12 mm (0.5 in).[4][5] Range is generally smaller at an average of 3 mm (0.1 in).[1]

A pseudoscorpion has eight legs with five to seven segments each; the number of fused segments is used to distinguish families and genera. They have two very long pedipalps with palpal chelae (pincers) which strongly resemble the pincers found on a scorpion.

The pedipalps generally consist of an immobile "hand" and mobile "finger", the latter controlled by an adductor muscle. A venom gland and duct are usually located in the mobile finger; the venom is used to immobilize the pseudoscorpion's prey. During digestion, pseudoscorpions exude a mildly corrosive fluid over the prey, then ingest the liquefied remains.

The abdomen, referred to as the opisthosoma, is made up of twelve segments, each protected by sclerotized plates (called tergites above and sternites below). The abdomen is short and rounded at the rear, rather than extending into a segmented tail and stinger like true scorpions. The color of the body can be yellowish-tan to dark-brown, with the paired claws often a contrasting color. They may have two, four or no eyes.[5]

Pseudoscorpions spin silk from a gland in their jaws to make disk-shaped cocoons for mating, molting, or waiting out cold weather. However, they do not have book lungs like true scorpions and the Tetrapulmonata. Instead they breathe exclusively through trachea, which open laterally through two pairs of spiracles on the posterior margins of the sternites of abdominal segments 3 and 4.[6]

Behavior

Some species have an elaborate mating dance, where the male pulls a female over a spermatophore previously laid upon a surface.[7] In other species, the male also pushes the sperm into the female genitals using the forelegs.[8] The female carries the fertilized eggs in a brood pouch attached to her abdomen, and the young ride on the mother for a short time after they hatch.[2] Between 20 and 40 young are hatched in a single brood; there may be more than one brood per year. The young go through three molts over the course of several years before reaching adulthood. Many species molt in a small, silken igloo that protects them from enemies during this vulnerable period.[9] After reaching adulthood, pseudoscorpions live two to three years. They are active in the warm months of the year, overwintering in silken cocoons when the weather grows cold. Smaller species live in debris and humus. Some species are arboreal, while others are phagophiles, eating parasites in an example of cleaning symbiosis. Some species are phoretic,[10] others may sometimes be found feeding on mites under the wing covers of certain beetles.

Distribution

There are more than 3,300 species of pseudoscorpions recorded in more than 430 genera, with more being discovered on a regular basis. They range worldwide, even in temperate to cold regions like Northern Ontario and above timberline in Wyoming's Rocky Mountains in the United States and the Jenolan Caves of Australia, but have their most dense and diverse populations in the tropics and subtropics, where they spread even to island territories like the Canary Islands, where around 25 endemic species have been found.[11] There are also two endemic species on the Maltese Islands.[1] Species have been found under tree bark, in leaf and pine litter, in soil, in tree hollows, under stones, in caves, at the seashore in the intertidal zone, and within fractured rocks.[2]

Chelifer cancroides is the species most commonly found in homes, where they are often observed in rooms with dusty books. There the tiny animals (2.5–4.5 mm or 0.10–0.18 in) can find their food like booklice and house dust mites. They enter homes by "riding along" attached to insects (known as phoresy). The insects employed are necessarily larger than the pseudoscorpion, or they are brought in with firewood.

Evolution

The oldest known fossil pseudoscorpion dates back 380 million years to the Devonian period.[12] It has all of the traits of a modern pseudoscorpion, indicating that the order evolved very early in the history of land animals.[13] As with most other arachnid orders, the pseudoscorpions have changed very little since they first appeared, retaining almost all the features of their original form.

Historical references

Pseudoscorpions were first described by Aristotle, who probably found them among scrolls in a library where they would have been feeding on booklice. Robert Hooke referred to a "Land-Crab" in his 1665 work Micrographia. Another reference in the 1780s, when George Adams wrote of "a lobster-insect, spied by some labouring men who were drinking their porter, and borne away by an ingenious gentleman, who brought it to my lodging."[14]

Classification

The following taxon numbers are calculated as of the end of 2012.[15]

- Order Pseudoscorpiones de Geer, 1778 (2 suborders)

- † Family Dracochelidae Schawaller, Shear and Bonamo, 1991 (1 fossil genus, 1 fossil species)

- Suborder Epiocheirata Harvey, 1992 (2 superfamilies)

- Superfamily Chthonioidea Daday, 1888 (4 families)

- Family Chthoniidae Daday, 1888 (28 genera, 650 species [3 fossil species])

- Family Lechytiidae Chamberlin, 1929 (1 genus, 23 species [1 fossil species])

- Family Pseudotyrannochthoniidae Beier, 1932 (5 genera, 49 species)

- Family Tridenchthoniidae Balzan, 1892 (15 genera, 71 species [1 fossil genus, 1 fossil species])

- Superfamily Feaelloidea Ellingsen, 1906 (2 families)

- Family Feaellidae Ellingsen, 1906 (1 genus, 12 species)

- Family Pseudogarypidae Chamberlin, 1923 (2 genera, 7 species [5 fossil species])

- Suborder Iocheirata Harvey, 1992 (5 superfamilies)

- Superfamily Neobisioidea Chamberlin, 1930 (7 families)

- Family Bochicidae Chamberlin, 1930 (12 genera, 42 species)

- Family Gymnobisiidae Beier, 1947 (4 genera, 11 species)

- Family Hyidae Chamberlin, 1930 (2 genera, 14 species)

- Family Ideoroncidae Chamberlin, 1930 (11 genera, 59 species)

- Family Neobisiidae Chamberlin, 1930 (33 genera, 595 species [4 fossil species])

- Family Parahyidae Harvey, 1992 (1 genus, 1 species)

- Family Syarinidae Chamberlin, 1930 (18 genera, 111 species)

- Superfamily Garypoidea Simon, 1879 (6 families)

- Family Garypidae Simon, 1879 (10 genera, 80 species)

- Family Garypinidae Daday, 1888 (21 genera, 76 species [2 fossil species])

- Family Geogarypidae Chamberlin, 1930 (3 genera, 60 species [3 fossil species])

- Family Larcidae Harvey, 1992 (2 genera, 15 species)

- Family Menthidae Chamberlin, 1930 (5 genera, 12 species)

- Family Olpiidae Banks, 1895 (36 genera, 268 species)

- Superfamily Cheiridioidea Hansen, 1894 (2 families)

- Family Cheiridiidae Hansen, 1894 (7 genera, 73 species [1 fossil genus, 3 fossil species])

- Family Pseudochiridiidae Chamberlin, 1923 (2 genera, 12 species [1 fossil species])

- Superfamily Sternophoroidea Chamberlin, 1923 (1 family)

- Family Sternophoridae Chamberlin, 1923 (3 genera, 20 species)

- Superfamily Cheliferoidea Risso, 1827 (4 families)

- Family Atemnidae Kishida, 1929 (21 genera, 178 species [1 fossil genus, 1 fossil species])

- Family Cheliferidae Risso, 1827 (58 genera, 273 species [5 fossil genus, 12 fossil species])

- Family Chernetidae Menge, 1855 (117 genera, 663 species [1 fossil genus, 3 fossil species])

- Family Withiidae Chamberlin, 1931 (36 genera, 158 species [1 fossil genus, 1 fossil species])

References

- Schembri, Patrick J.; Baldacchino, Alfred E. (2011). Ilma, Blat u Hajja: Is-Sisien tal-Ambjent Naturali Malti (in Maltese). p. 66. ISBN 978-99909-44-48-8.

- Pennsylvania State University, Department: Entomological Notes: Pseudoscorpion Fact Sheet

- M. Beier (1961). "Pseudoscorpione von der Insel Ascension" [Pseudoscorpions from Ascension Island]. Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13th ser. (in German). 3 (34): 593–598. doi:10.1080/00222936008651063.

- "Endemic invertebrates" (PDF). Ascension Island Conservation Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-09.

- "Pseudoscorpions". Agricultural Research Council (South Africa). Archived from the original on 2012-02-22.

- Discontinuous gas exchange in a tracheate arthropod, the pseudoscorpion Garypus californicus: occurrence, characteristics and temperature dependence

- Peter Weygoldt (1966). "Spermatophore web formation in a pseudoscorpion". Science. 153 (3744): 1647–1649. Bibcode:1966Sci...153.1647W. doi:10.1126/science.153.3744.1647. PMID 17802636.

- Heather C. Proctor (1993). "Mating biology resolves trichotomy for cheliferoid pseudoscorpions (Pseudoscorpionida, Cheliferoidea)" (PDF). Journal of Arachnology. 21 (2): 156–158.

- Ross Piper (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Press.

- "Pseudoscorpions". South African National Survey of Arachnids. Archived from the original on 2012-01-07.

- Volker Mahnert (2011). "A nature's treasury: pseudoscorpion diversity of the Canary Islands, with the description of nine new species (Pseudoscorpiones, Chthoniidae, Cheiridiidae) and new records" (PDF). Revista Ibérica de Aracnología. 19: 27–45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- William A. Shear, Wolfgang Schawaller & Patricia M. Bonamo (1989). "Record of Palaeozoic pseudoscorpions". Nature. 342 (6242): 527–529. Bibcode:1989Natur.341..527S. doi:10.1038/341527a0.

- Wolfgang Schawaller, William A. Shear & Patricia M. Bonamo (1991). "The first Paleozoic pseudoscorpions (Arachnida, Pseudoscorpionida)". American Museum Novitates. 3009. hdl:2246/5041.

- Adams, George (1787): Essays on the Microscope. First edition. (London: Robert Hindmarsh)

- Harvey, Mark S. (2013). Zhang, Z.-Q. (ed.). "Order Pseudoscorpiones In: Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013)". Zootaxa. 3703.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pseudoscorpiones. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Pseudoscorpiones |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Book-Scorpion. |

- Mark Harvey (2011). Pseudoscorpions of the World

- Joseph C. Chamberlin (1931): The Arachnid Order Chelonethida. Stanford University Publications in Biological Science. 7(1): 1–284.

- Clarence Clayton Hoff (1958): List of the Pseudoscorpions of North America North of Mexico. American Museum Novitates. 1875. PDF

- Max Beier (1967): Pseudoscorpione vom kontinentalen Südost-Asien. Pacific Insects 9(2): 341–369. PDF

- Peter Weygoldt (1969). The biology of pseudoscorpions. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 9780674074255.

- P. D. Gabbutt (1970): Validity of Life History Analyses of Pseudoscorpions. Journal of Natural History 4: 1–15.

- W. B. Muchmore (1982): Pseudoscorpionida. In "Synopsis and Classification of Living Organisms." Vol. 2. Parker, S.P.

- J. A. Coddington, S. F. Larcher & J. C. Cokendolpher (1990): The Systematic Status of Arachnida, Exclusive of Acari, in North America North of Mexico. In "Systematics of the North American Insects and Arachnids: Status and Needs." National Biological Survey 3. Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- Mark S. Harvey (1991): Catalogue of the Pseudoscorpionida. (edited by V . Mahnert). Manchester University Press, Manchester.