Charrúa

The Charrúa are an Amerindian, Indigenous People or Indigenous Nation of the Southern Cone in present-day Uruguay[5] and the adjacent areas in Argentina (Entre Ríos) and Brazil (Rio Grande do Sul).[6][7] They were a semi-nomadic people who sustained themselves mainly through hunting and gathering. Since resources were not permanent in every region, they would constantly be on the move.[8] Rain, drought, and other environmental factors determined their movement. For this reason they are often called nomadas estacionales, which means "seasonal nomads".[9]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Tribe in reemergence[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Charruan languages | |

| Religion | |

| Animism |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Uruguay |

|

|

Early History

|

|

Independent State |

|

20th Century

|

|

Military Regime

|

|

Modern Uruguay

|

|

|

History

The life of the Charrúas before contact with the Spanish Colonists remains to a large extent a mystery. The reason for this is that most knowledge about the Charrúas comes from Spanish contact with them. Chroniclers such as the Jesuit Pedro Lozano accused the Charrúan people of killing the Spanish explorer Juan Díaz de Solís during his 1515 voyage up the Río de la Plata. This was a crucial moment since it shows that the Charrúas were going to resist the Spanish Invaders.[10] Following the arrival of European settlers, the Charrúa, along with the Chana, strongly resisted their territorial invasion. In the 18th and 19th centuries the Charrúa were confronted by cattle exploitation that strongly altered their way of life, causing famine and forcing them to rely on cows and sheep. However, these were in that epoch increasingly privatized . Malones (raids) were resisted by settlers who freely shot any indigenous people who were in their way.

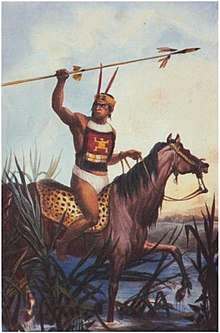

Physical description

This is a descriptive statement by Jose Imbelloni "The skull is bulky and often presents a high bone thickness and significant weight, especially in the macrosomatic groups preserved in the south, the cheekbones are powerful and the chin is thick and protruding, the face is elongated and the nasal index leptorrino (narrow nose and long.) The construction of the skeleton is massive, at times enormous. Aside to this somewhat coarse macrosomatic canon, we must take into account the reciprocal proportions of the members, which point to a remarkable harmony. The athletic cut and balance of the muscular masses make the pámpido one of the most superb models of the human organism. With regard to physiognomy, there is almost no sexual dimorphism, and men are very little different from women. Current color of intense pigmentation, with bronzed reflections. Dark, hard and smooth hair." [11]

Genocide

The drastic demographic reduction of the Charrúa did not occur until the first president of Uruguay Fructuoso Rivera. Although Rivera initially maintained good relations with the Charrúa, the increasing dominance of the whites and desires of expansion led to hostilities.[12] He therefore organized a genocide campaign known as La Campaña de Salsipuedes in 1831. This campaign was composed of three different attacks in three different places: "El Paso del Sauce del Queguay", "El Salsipuedes", and a passage known as "La cueva del Tigre".[13] Legend has it that the first attack was a betrayal. The president Fructuoso Rivera knew the tribal leaders and called them to his Barracks by the river later named Salsipuedes. He claimed that he needed their help to defend territory and that they should join together, however, once the Charrúas were drunk and off their guard, the Uruguayan soldiers attacked them. The following two attacks were carried out to eliminate the Charrúas that had escaped or had not been present. It is said that since 11 April 1831, when the Salsipuedes (meaning "Get-out-if-you-can") campaign was launched by a group led by Bernabé Rivera, nephew of Fructuoso Rivera, the Charrúa were then officially claimed to be extinct.

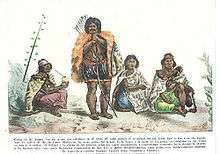

Four surviving Charrúa were captured at Salsipuedes. The directory of the Oriental School of Montevideo thought a nearly extinct race would spark the interest of French scientists and public.[14] They were Senacua Sénaqué, a medicine man; Vaimaca-Pirú Sira, a warrior; and a young couple, Laureano Tacuavé Martínez and María Micaëla Guyunusa. All four were taken to Paris, France, in 1833, where they were exhibited to the public. The display was not a success and they all soon died in France, including a baby daughter born to Sira and Guyunusa, and adopted by Tacuavé.[6] The child was named María Mónica Micaëla Igualdad Libertad by the Charrúa, yet she was filed by the French as Caroliné Tacouavé.[15][16] A monumental sculpture, Los Últimos Charrúas was built in their memory in Montevideo, Uruguay.[17]

After Salsipuedes, the Charrúa were gradually dispossessed of their sovereignty while the new State was affirming its jurisdiction over the whole territory. According to the Argentine census of 2001, there are 676 Charrúa living in the province of Entre Ríos.

Legacy

Since the 1980s—after Uruguay's last dictatorship—a group of people has been affirming and vindicating their Charruan ancestry. In 1989, they gathered around Adench (Asociación de los descendientes de la Nación Charrúa), by then they self-recognized themselves as "descendants". In 2005, another organization was formed - CONACHA (Consejo de la Nación Charrúa) - where families came out of clandestinity and self-recognized themselves publicly as Charrúa.

Not much is known about the Charrúa due to their cognitive erasure at an early time in Uruguayan history. The only surviving documents that concern the Charrúa are those of Spanish explorers, archaeologists, and anthropologists. A new body of literature is currently emerging about their oral history, contemporary ethnogenesis and activism.

It is believed that there are approximately between 160 thousand and 300 thousand individuals in Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil today, that are descendants from surviving Charrúa.[18]

Uruguayans refer to themselves as "charrúa" when in the context of a competition or battle against a foreign contingent. In situations in which Uruguayans display bravery in the face of overwhelming odds, the expression "garra charrúa" (Charrúan tenacity) is used to refer to victory in the face of certain defeat.

There is a Charrúa cemetery located in Piriápolis in the Maldonado Department.[19]

The Uruguay national football team is nicknamed "Los Charrúas" and a local rugby side in Porto Alegre are also named after the nation (see: Charrua Rugby Clube)

"Charrua" is also one name of a Brazilian military tank used for troop transportation.

Tabaré was published in 1888; it being an epic poem by Juan Zorrilla de San Martín about a Charrúa and his love for a Spanish woman.

The rivuline Austrolebias charrua was named after them.

A street in Montevideo in the neighbourhoods of Pocitos and Cordón is named Charrúa.

In August 1989 the Association of the Descendants of the Charrúa Nation was created to rescue, conserve, and promulgate the knowledge and presence of indigenous peoples in Uruguay.

See also

- Indigenous peoples in Uruguay

- Minuane people

Notes

- "Tidos como extintos, índios charrua sobreviveram 'invisíveis' por décadas e hoje lutam por melhores condições de vida - BBC - UOL Notícias". UOL Notícias (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- "Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas 2010" (PDF) (in Spanish). 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- "Uruguay en crigras" (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "Quadro Geral dos Povos - Povos Indígenas no Brasil". pib.socioambiental.org (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- Renzo Pi Hugarte. "Aboriginal blood in Uruguay" (in Spanish). Raíces Uruguay. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- Burford 2011, p. 16.

- Alayón, Wilfredo (28 March 2011). "Uruguay and the memory of the Charrúa tribe". The Prisma. Retrieved 20 Dec 2011.

- Acosta y Lara, Eduardo, F. El Pais Charrua. Fundacion BankBoston, 2002.

- Acosta y Lara, Eduardo, F. El Pais Charrua. Fundacion BankBoston, 2002.

- Historia de la conquista del Paraguay, Rio de la Plata y Tucuman, Volumen 1, pág. 27. Autor: Pedro Lozano, 1755. Editor: Andrés Lamas. Casa Editora "Imprenta Popular", 1874

- IMBELLONI, José, "De Historia Primitiva de América. Los grupos raciales aborígenes". Madrid, Cuadernos de Historia Primitiva Año II, N° 2. 1957

- Alayón, Wilfredo (28 March 2011). "Uruguay and the memory of the Charrúa tribe". The Prisma. Retrieved 20 Dec 2011.

- Acosta y Lara, Eduardo, F. El Pais Charrua. Fundacion BankBoston, 2002.

- Darío Arce. «Nuevos datos sobre el destino de Tacuavé y la hija de Guyunusa». Consultado el 1 de julio de 2013.

- Charrua Hapkido y Tkd Paysandu (May 21, 2012). "El Parto de María Micaëla Guyunusa". chancharrua.wordpress.com (in Spanish). Charrúas del Uruguay, La nación Charrúa. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "El Parto de María Micaëla Guyunusa". indiauy.tripod.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- Burford 2011, p. 119.

- Alayón, Wilfredo (28 March 2011). "Uruguay and the memory of the Charrúa tribe". The Prisma. Retrieved 20 Dec 2011.

- Burford 2011, p. 173.

References

- Burford, Tim (2011). The Bradt Travel Guide Uruguay. Bucks, UK: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-316-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arce, Dario (2018). L'URUGUAY, UNE NATION D'EXTRÊME-OCCIDENT AU MIROIR DE SON HISTOIRE INDIENNE. Editions l'Harmattan, Paris.

- Víctora, Ceres Gomes; Ruas-Neto, Antonio Leite (2012-08-31). "Querem matar os 'últimos Charruas': Sofrimento social e 'luta' dos indígenas que vivem nas cidades". Revista ANTHROPOLÓGICAS. 22 (1). ISSN 2525-5223. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Rodríguez, Mariela Eva (2018). "DEVENIR CHARRÚA EN EL URUGUAY". Abya-yala: Revista sobre Acesso à Justiça e Direitos nas Américas. 2 (2): 408–420. ISSN 2526-6675. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Pedroso, Anayara Fantinel; Brito, Antonio José Guimarães (2016-12-31). "Vidas do sul: Identidade, Direito e Resistência na América Latina". Revista Latino-Americana de Estudos em Cultura e Sociedade. 2 (4): 556–575. doi:10.23899/relacult.v2i4.352. ISSN 2525-7870. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Ely, Lara. "Uruguai. Espiritualmente ligados à Terra, Charruas querem reconhecimento". Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Arn, Iván (2009). Más allá de la relación entre Identidad-Alteridad. La particularidad latinoamericana y la función del Estado. V Jornadas de Jóvenes Investigadores. Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Lucas, Lara Ely. "O país sem índios. Entrevista com Nicolás Soto e Leonardo Rodríguez". Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Corte, Gomez; Gomeza, Jose Ignacio (2016). "EM BUSCA DA MEMÓRIA E DA IDENTIDADE: A RESISTÊNCIA DO POVO CHARRUA NO URUGUAI". XXX Reunião da Associação Brasileira de Antropologia: 21. Archived from the original on 2019-05-06. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Olivera, Andrea (2014). "Etnografía decolonial con colectivos charrúas: reflexionando sobre interconocimientos" (PDF). Anuario de Antropología Social y Cultural en Uruguay (in Spanish). 12: 139–153.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charrúas. |

- Renzo Pi Hugarte (1969). "El Uruguay indígena" (PDF) (in Spanish). Nuestra Tierra. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- Charrúa artwork, National Museum of the American Indian