Chapel Royal, Dublin

The Chapel Royal in Dublin Castle was the official Church of Ireland chapel of the Household of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1814 until the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. The creation of the new Irish state terminated the office of Lord Lieutenant and British government control in Ireland.[2]

| The Chapel Royal | |

|---|---|

An Seipeal Rioga | |

A view of the exterior | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Church of Ireland (1814–1922) Roman Catholic (1943–1982) None (1922–1943; 1983–present) |

| Province | Leinster |

| Year consecrated | 1814[1] |

| Status | Museum |

| Location | |

| Location | Dublin Castle, Dublin, Ireland |

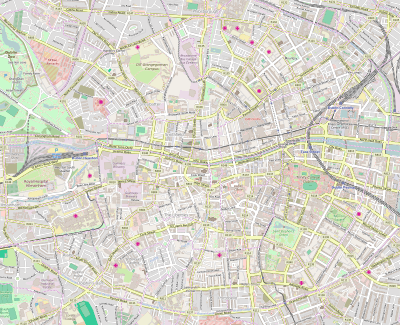

Shown within Central Dublin | |

| Geographic coordinates | 53°20′35″N 6°15′59″W |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Francis Johnston |

| Style | Gothic revival |

Construction

Designed by Francis Johnston (1760–1829), the foremost architect working in Ireland in the early 19th century, and architect to the Board of Works, the chapel contains one of the finest Gothic revival interiors in Ireland. Replacing an earlier undistinguished 18th-century church that suffered structural problems through being built on soft ground close to the site of the original castle moat, the new Chapel Royal was built using a timber frame to make it as light as possible. Indeed, so difficult was the nature of the site that the chapel took seven years to build, though a contributory factor in both time and budget was the "sheer opulence"[3] of its interior.

The foundation stone was laid by the Lord Lieutenant, John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, on 15 February 1807. It was completed behind schedule (the budget also substantially overran) and opened on Christmas Day, 1814, when Charles Whitworth, 1st Earl Whitworth was Lord Lieutenant. Lord Whitworth contributed the centre portion of the large stained-glass window above the altar, which he had purchased while in Paris,[4] and which reputedly had come from Russia (he had been plenipotentiary in St. Petersburg in the 1790s). The surroundings are painted glass, executed by a Mr. Bradley in Dublin. At the apex of the window are the arms of Lord Whitworth.

The decoration of the ceiling of the interior was done by George Stapleton (son of Michael Stapleton), a leading stuccodore of the time, while sculptor Edward Smyth (responsible for the "river heads" on the Custom House) and his son John Smyth (responsible for the statues on the GPO) carved the larger figures. Over the chancel window are three life-size figures representing Faith, Hope and Charity. Over the galleries are heads representing Piety and Devotion. All the interior vaulting and columns are cast in timber and feature a paint wash (faux pierre) to give the effect of stone. It was described as having "the most flamboyant and luxurious Dublin interior of its era."[3]

The exterior was clad in a thin layer of "fine limestone from Tullamore quarry",[5] and famously features over 90 carved heads, including those of Brian Boru, St. Patrick, Archbishop Ussher and Jonathan Swift, done by Edward and John Smyth.[6]

Historical features

This was the third chapel in the castle, and the second on this spot, since medieval times. Before the completion of the Chapel Royal the Lords Lieutenant their entourage and hangers-on sometimes attended St Werburgh's church at the rear of the Castle to the west. The enormous pulpit that used to dominate the Chapel Royal has now been removed to St. Werburgh's.[2]

Behind one of the galleries is a passage that leads to the bedrooms in the State Apartments. This was used by the Lord Lieutenant and his entourage when they were staying at the Castle. His pew (or throne) was in the centre of the right-hand gallery. Directly facing him was the place for the bishop. Lord Whitworth's arms appear directly at the Lord Lieutenant's position, a most prominent spot.

The organ case was constructed in 1857 to house a new organ by William Telford of Dublin, which replaced an earlier instrument by William Gray of London installed in 1815. A new organ was built by the firm Gray and Davison in 1900 into the same case. Although the case was restored in 2008, the organ is no longer playable as the pipework and mechanisms have been removed.[7]

As each Lord Lieutenant left office, their coat of arms was carved on the gallery, and then, when space ran out, placed in a window of the chapel. It was noted by Irish nationalists that the last window available was taken up by the man who proved to be the last Lord Lieutenant, Viscount Fitzalan (himself a Catholic).[8]

Present day

In 1943, the Chapel was consecrated by Archbishop of Dublin John Charles McQuaid as a Roman Catholic military church, and in 1944 was renamed the Church of the Most Holy Trinity. The Stations of the Cross were carved by the monks in Glenstal Abbey and presented to the church in 1946. Increasing structural problems caused its closure in the early 1980s. The building was restored and reopened in the early 1990s, although it has not since been used for worship. It is occasionally used for concerts and other events.

The Chapel was used in the television series The Tudors for scenes including the trial of Thomas More.

See also

References and sources

- Notes

- "Chapel Royal: A Bicentennial Celebration". The Journal of Music: News, Reviews & Opinion | Music Jobs & Opportunities.

- Costello (1999), p. 69

- Lucey (2007), p. 91

- Johnston (1896), p. 1

- Johnston (1896), p. 2

- McCarthy (2004), p. 128

- David O'Shea, 'Music and Liturgy at the Chapel Royal' in Campbell and Derham (2015)

- McCarthy (2004), p. 129

- Sources

- Lucey, Conor (2007). The Stapleton Collection: Designs for the Irish neoclassical interior. Tralee: Churchill Press. ISBN 978-0-9550246-2-7.

- McCarthy, Denis; Benton, David (2004). Dublin Castle: at the heart of Irish History. Dublin: Irish Government Stationery Office. ISBN 0-7557-1975-1.

- Johnston, Francis (1896). The Chapel Royal, Dublin Castle (reprint). Dublin: The Irish Builder (trade journal).

- Costello, Peter (1999). Dublin Castle, in the life of the Irish nation. Dublin: Wolfhound Press. ISBN 0-86327-610-5.

- Campbell, Myles; Derham, William (2015). The Chapel Royal, Dublin Castle: An Architectural History. Trim: Office of Public Works. ISBN 9781406428902.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chapel Royal, Dublin. |

- Ireland.archiseek.com, entry on Chapel Royal (including pictures)