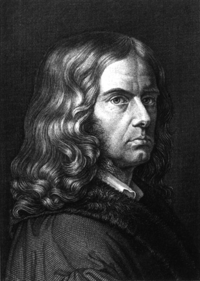

Adelbert von Chamisso

Adelbert von Chamisso (German pronunciation: [ˈaːdl̩bɛʁt fɔn ʃaˈmɪso]; 30 January 1781 – 21 August 1838) was a German poet and botanist, author of Peter Schlemihl, a famous story about a man who sold his shadow. He was commonly known in French as Adelbert de Chamisso (or Chamissot) de Boncourt, a name referring to the family estate at Boncourt.

Adelbert von Chamisso | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Louis Charles Adélaïde de Chamissot 30 January 1781 Ante, Champagne, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 21 August 1838 (aged 57) Berlin, Province of Brandenburg, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | German |

| Genre | Poetry, novella |

Life

The son of Louis Marie, Count of Chamisso, by his marriage to Anne Marie Gargam, Chamisso began life as Louis Charles Adélaïde de Chamissot at the château of Boncourt at Ante, in Champagne, France, the ancestral seat of his family.[1] His name appears in several forms, one of the most common being Ludolf Karl Adelbert von Chamisso.[2]

In 1790, the French Revolution drove his parents out of France with their seven children, and they went successively to Liège, the Hague, Würzburg, and Bayreuth, and possibly Hamburg where he reportedly met both a younger boy in Johann August Wilhelm Neander and another younger boy in Karl August Varnhagen von Ense before settling in Berlin. There, in 1796 the young Chamisso was fortunate in obtaining the post of page-in-waiting to the queen of Prussia, and in 1798 he entered a Prussian infantry regiment as an ensign to train for a career as an army officer.

Shortly thereafter, thanks to the Peace of Tilsit, his family was able to return to France, but Chamisso remained in Prussia and continued his military career. He had little formal education, but while in the Prussian military service in Berlin he assiduously studied natural science for three years. In collaboration with Varnhagen von Ense, in 1803 he founded the Berliner Musenalmanach, the publication in which his first verses appeared. The enterprise was a failure, and, interrupted by the Napoleonic wars, it came to an end in 1806. It brought him, however, to the notice of many of the literary celebrities of the day and established his reputation as a rising poet.[1]

Chamisso had become a lieutenant in 1801, and in 1805 he accompanied his regiment to Hamelin, where he shared in the humiliation of the town's treasonable capitulation the next year. Placed on parole, he went to France, but both his parents were dead; returning to Berlin in the autumn of 1807, he obtained his release from the Prussian service early the following year. Homeless and without a profession, disillusioned and despondent, Chamisso lived in Berlin until 1810, when through the services of an old friend of the family he was offered a professorship at the lycée at Napoléonville in the Vendée.[1]

He set out to take up the post, but instead joined the circle of Madame de Staël, and followed her in her exile to Coppet in Switzerland, where, devoting himself to botanical research, he remained nearly two years. In 1812 he returned to Berlin, where he continued his scientific studies. In the summer of the eventful year, 1813, he wrote the prose narrative Peter Schlemihl, the man who sold his shadow. This, the most famous of all his works, has been translated into most European languages (English by William Howitt). It was written partly to divert his own thoughts and partly to amuse the children of his friend Julius Eduard Hitzig.[1]

In 1815, Chamisso was appointed botanist to the Russian ship Rurik, fitted out at the expense of Count Nikolay Rumyantsev, which Otto von Kotzebue (son of August von Kotzebue) commanded on a scientific voyage round the world.[1] He collected at the Cape of Good Hope in January 1818 in the company of Krebs, Mund and Maire.[3] His diary of the expedition (Tagebuch, 1821) is a fascinating account of the expedition to the Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. During this trip Chamisso described a number of new species found in what is now the San Francisco Bay Area. Several of these, including the California poppy, Eschscholzia californica, were named after his friend Johann Friedrich von Eschscholtz, the Rurik's entomologist. In return, Eschscholtz named a variety of plants, including the genus Camissonia, after Chamisso. On his return in 1818 he was made custodian of the botanical gardens in Berlin, and was elected a member of the Academy of Sciences, and in 1819 he married his friend Hitzig's foster daughter Antonie Piaste (1800–1837). He became a leading member of the Serapion Brethren, a literary circle around E. T. A. Hoffmann.

In 1827, partly for the purpose of rebutting the charges brought against him by Kotzebue, he published Views and Remarks on a Voyage of Discovery, and Description of a Voyage Round the World. Both works display great accuracy and industry. His last scientific labor was a tract on the Hawaiian language. Chamisso's travels and scientific researches restrained for a while the full development of his poetical talent, and it was not until his forty-eighth year that he turned back to literature. In 1829, in collaboration with Gustav Schwab, and from 1832 in conjunction with Franz von Gaudy, he brought out the Deutscher Musenalmanach, in which his later poems were mainly published.[1]

Chamisso died in Berlin at the age of 57. His grave is preserved in the Protestant Friedhof III (Cemetery No. 3 of the congregations of Jerusalem's Church and the New Church) in Berlin-Kreuzberg, to the south of the Hallesches Tor.

Botanical work

Chamisso is chiefly remembered for his work as a botanist; his most important contribution, done in conjunction with Diederich Franz Leonhard von Schlechtendal, was the description of many of the most important trees of Mexico in 1830–1831. Also, his Bemerkungen und Ansichten, published in an incomplete form in Kotzebue's Entdeckungsreise (Weimar, 1821) and more completely in Chamisso's Collected Works (1836), and the botanical work, Übersicht der nutzbarsten und schädlichsten Gewächse in Norddeutschland (Review of the Most Useful and the Most Noxious Plants of North Germany, with Remarks on Scientific Botany), of 1829, are esteemed for their careful treatment of their subjects.[1]

The genera Chamissoa Kunth (Amaranthaceae) and Camissonia Link (Onagraceae) and many species were named in his honor.

Belles lettres

Chamisso's earliest writings, which include a verse translation of the tragedy Le Comte de Comminge in which "heilsam" is used in place of "heilig", show a 20-year-old still struggling to master his new language, and a number of his early poems are in French. Between 1801 and 1804 he became closely associated with other writers and edited their journal.

As a poet Chamisso's reputation stands high. Frauenliebe und -leben (1830), a cycle of lyrical poems set to music by Robert Schumann, by Carl Loewe, and by Franz Paul Lachner, is particularly famous. Also noteworthy are Schloss Boncourt and Salas y Gomez. He often deals with gloomy or repulsive subjects; and even in his lighter and gayer productions there is an undertone of sadness or of satire. In the lyrical expression of the domestic emotions he displays a fine felicity, and he knew how to treat with true feeling a tale of love or vengeance. Die Löwenbraut may be taken as a sample of his weird and powerful simplicity; and Vergeltung is remarkable for a pitiless precision of treatment. The first collected edition of Chamisso's works was edited by Hitzig and published in six volumes in 1836.[1]

See also

Notes

-

- Rodolfo E.G. Pichi Sermolli. 1996. Authors of Scientific Names in Pteridophyta. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 978-0-947643-90-4

- "Botanical Exploration of Southern Africa" - Gunn & Codd (1981)

- IPNI. Cham.

- Brummitt, R. K.; C. E. Powell (1992). Authors of Plant Names. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 978-1-84246-085-6.

References

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adelbert von Chamisso. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Adelbert von Chamisso |

| Wikispecies has information related to Adelbert von Chamisso |

- Works by Adelbert von Chamisso at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Adelbert von Chamisso at Internet Archive

- Works by Adelbert von Chamisso at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Wonderful History of Peter Schlemihl, 2005 translation by Michael Haldane

- Biographical sketch (1893) at Google Books

- Hall of Fame-Medusozoa

- Georg Friedrich Kaulfuss and Adelbert von Chamisso: Enumeratio filicum quas in itinere circa terram legit cl. Adalbertus de Chamisso etc. 1824, on GoogleBooks

- Biography and works on Zeno

- Adelbert von Chamisso at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Adelbert von Chamisso at Library of Congress Authorities, with 106 catalogue records