Mupirocin

Mupirocin, sold under the brand name Bactroban among others, is a topical antibiotic useful against superficial skin infections such as impetigo or folliculitis.[3][4] It may also be used to get rid of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) when present in the nose without symptoms.[3] Due to concerns of developing resistance, use for greater than ten days is not recommended.[4] It is used as a cream or ointment applied to the skin.[3]

| |

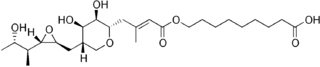

Pseudomonic acid A (PA-A), the principal component of mupirocin | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Bactroban, others |

| Other names | muciprocin[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a688004 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 97% |

| Elimination half-life | 20 to 40 minutes |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.106.215 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C26H44O9 |

| Molar mass | 500.629 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 77 to 78 °C (171 to 172 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include itchiness and rash at the site of application, headache, and nausea.[3] Long term use may result in increased growth of fungi.[3] Use during pregnancy and breastfeeding appears to be safe.[3] Mupirocin is in the carboxylic acid class of medications.[5] It works by blocking a bacteria's ability to make protein, which usually results in bacterial death.[3]

Mupirocin was initially isolated in 1971 from Pseudomonas fluorescens.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[7] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$2.10 for a 15 g tube.[8] In the United States, a course of treatment costs $25 to $50.[9] In 2017, it was the 186th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than three million prescriptions.[10][11]

Medical uses

Mupirocin is used as a topical treatment for bacterial skin infections, for example, furuncle, impetigo, open wounds, which are typically due to infection by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes. It is also useful in the treatment of superficial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections.[12] Mupirocin is inactive for most anaerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, mycoplasma, chlamydia, yeast and fungi.[13]

Intranasal mupirocin before surgery is effective for prevention of post-operative wound infection with Staphylcoccus aureus and preventative intranasal or catheter-site treatment is effective for reducing the risk of catheter site infection in persons treated with chronic peritoneal dialysis.[14]

Resistance

Shortly after the clinical use of mupirocin began, strains of Staphylococcus aureus that were resistant to mupirocin emerged, with nares clearance rates of less than 30% success.[15][16] Two distinct populations of mupirocin-resistant S. aureus were isolated. One strain possessed low-level resistance, MuL, (MIC = 8–256 mg/L) and another possessed high-level resistance, MuH, (MIC > 256 mg/L).[15] Resistance in the MuL strains is probably due to mutations in the organism's wild-type isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase. In E. coli IleRS, a single amino acid mutation was shown to alter mupirocin resistance.[17] MuH is linked to the acquisition of a separate Ile synthetase gene, MupA.[18] Mupirocin is not a viable antibiotic against MuH strains. Other antibiotic agents, such as azelaic acid, nitrofurazone, silver sulfadiazine, and ramoplanin have been shown to be effective against MuH strains.[15]

Most strains of Cutibacterium acnes, a causative agent in the skin disease acne vulgaris, are naturally resistant to mupirocin.[19]

The mechanism of action of mupirocin differs from other clinical antibiotics, rendering cross-resistance to other antibiotics unlikely.[15] However, the MupA gene may co-transfer with other antibacterial resistance genes. This has been observed already with resistance genes for triclosan, tetracycline, and trimethoprim.[15] It may also result in overgrowth of non-susceptible organisms.

Mechanism of action

Pseudomonic acid inhibits isoleucine tRNA synthetase in bacteria,[12] leading to depletion of isoleucyl-tRNA and accumulation of the corresponding uncharged tRNA. Depletion of isoleucyl-tRNA results in inhibition of protein synthesis. The uncharged form of the tRNA binds to the aminoacyl-tRNA binding site of ribosomes, triggering the formation of (p)ppGpp, which in turn inhibits RNA synthesis.[20] The combined inhibition of protein synthesis and RNA synthesis results in bacteriostasis. This mechanism of action is shared with furanomycin, an analog of isoleucine.[21]

Biosynthesis

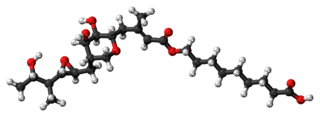

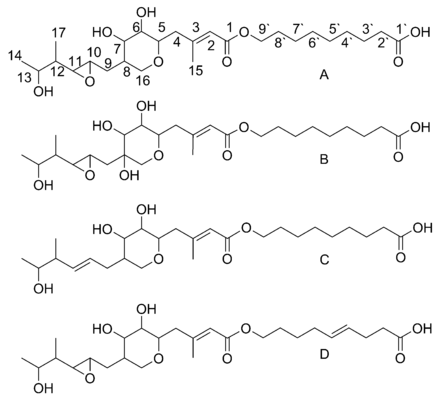

Mupirocin is a mixture of several pseudomonic acids, with pseudomonic acid A (PA-A) constituting greater than 90% of the mixture. Also present in mupirocin are pseudomonic acid B with an additional hydroxyl group at C8,[24] pseudomonic acid C with a double bond between C10 and C11, instead of the epoxide of PA-A,[25] and pseudomonic acid D with a double bond at C4` and C5` in the 9-hydroxy-nonanoic acid portion of mupirocin.[26]

Biosynthesis of pseudomonic acid A

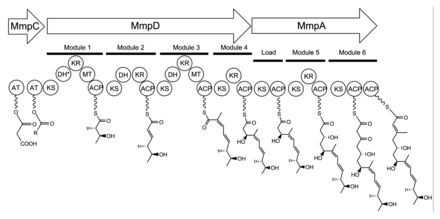

The 74 kb mupirocin gene cluster contains six multi-domain enzymes and twenty-six other peptides (Table 1).[22] Four large multi-domain type I polyketide synthase (PKS) proteins are encoded, as well as several single function enzymes with sequence similarity to type II PKSs.[22] Therefore, it is believed that mupirocin is constructed by a mixed type I and type II PKS system. The mupirocin cluster exhibits an atypical acyltransferase (AT) organization, in that there are only two AT domains, and both are found on the same protein, MmpC. These AT domains are the only domains present on MmpC, while the other three type I PKS proteins contain no AT domains.[22] The mupirocin pathway also contains several tandem acyl carrier protein doublets or triplets. This may be an adaptation to increase the throughput rate or to bind multiple substrates simultaneously.[22]

Pseudomonic acid A is the product of an esterification between the 17C polyketide monic acid and the 9C fatty acid 9-hydroxy-nonanoic acid. The possibility that the entire molecule is assembled as a single polyketide with a Baeyer-Villiger oxidation inserting an oxygen into the carbon backbone has been ruled out because C1 of monic acid and C9' of 9-hydroxy-nonanoic acid are both derived from C1 of acetate.[27]

| Gene | Function |

|---|---|

| mupA | FMNH2 dependent oxygenase |

| mmpA | KS ACP KS KR ACP KS ACP ACP |

| mupB | 3-oxoacyl-ACP synthase |

| mmpB | KS DH KR ACP ACP ACP TE |

| mmpC | AT AT |

| mmpD | KS DH KR MeT ACP KS DH KR ACP KS DH KR MeT ACP KS KR ACP |

| mupC | NADH/NADPH oxidoreductase |

| macpA | ACP |

| mupD | 3-oxoacyl-ACP reductase |

| mupE | enoyl reductase |

| macpB | ACP |

| mupF | KR |

| macpC | ACP |

| mupG | 3-oxoacyl-ACP synthase I |

| mupH | HMG-CoA synthase |

| mupJ | enoyl-CoA hydratase |

| mupK | enoyl-CoA hydratase |

| mmpE | KS hydrolase |

| mupL | putative hydrolase |

| mupM | isoleucyl-tRNA synthase |

| mupN | phosphopantetheinyl transferase |

| mupO | cytochrome P450 |

| mupP | unknown |

| mupQ | acyl-CoA synthase |

| mupS | 3-oxoacyl-ACP reductase |

| macpD | ACP |

| mmpF | KS |

| macpE | ACP |

| mupT | ferredoxin dioxygenase |

| mupU | acyl-CoA synthase |

| mupV | oxidoreductase |

| mupW | dioxygenase |

| mupR | N-AHL-responsive transcriptional activator |

| mupX | amidase/hydrolase |

| mupI | N-AHL synthase |

Monic acid biosynthesis

Biosynthesis of the 17C monic acid unit begins on MmpD (Figure 1).[22] One of the AT domains from MmpC may transfer an activated acetyl group from acetyl-Coenzyme A (CoA) to the first ACP domain. The chain is extended by malonyl-CoA, followed by a SAM-dependent methylation at C12 (see Figure 2 for PA-A numbering) and reduction of the B-keto group to an alcohol. The dehydration (DH) domain in module 1 is predicted to be non-functional due to a mutation in the conserved active site region. Module 2 adds another two carbons by the malonyl-CoA extender unit, followed by ketoreduction (KR) and dehydration. Module three adds a malonyl-CoA extender unit, followed by SAM-dependent methylation at C8, ketoreduction, and dehydration. Module 4 extends the molecule with a malonyl-CoA unit followed by ketoreduction.

Assembly of monic acid is continued by the transfer of the 12C product of MmpD to MmpA.[22] Two more rounds of extension with malonyl-CoA units are achieved by module 5 and 6. Module 5 also contains a KR domain.

Post-PKS tailoring

The keto group at C3 is replaced with a methyl group in a multi-step reaction (Figure 3). MupG begins by decarboxylating a malonyl-ACP. The alpha carbon of the resulting acetyl-ACP is linked to C3 of the polyketide chain by MupH. This intermediate is dehydrated and decarboxylated by MupJ and MupK, respectively.[22]

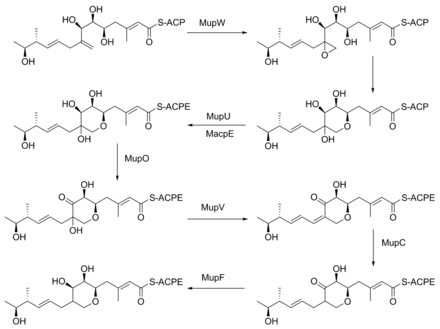

The formation of the pyran ring requires many enzyme-mediated steps (Figure 4). The double bond between C8 and C9 is proposed to migrate to between C8 and C16.[23] Gene knockout experiments of mupO, mupU, mupV, and macpE have eliminated PA-A production.[23] PA-B production is not removed by these knockouts, demonstrating that PA-B is not created by hydroxylating PA-A. A knockout of mupW eliminated the pyran ring, identifying MupW as being involved in ring formation.[23] It is not known whether this occurs before or after the esterification of monic acid to 9-hydroxy-nonanoic acid.

The epoxide of PA-A at C10-11 is believed to be inserted after pyran formation by a cytochrome P450 such as MupO.[22] A gene knockout of mupO abolished PA-A production but PA-B, which also contains the C10-C11 epoxide, remained.[23] This indicates that MupO is either not involved or is not essential for this epoxidation step.

9-Hydroxy-nonanoic acid biosynthesis

The nine-carbon fatty acid 9-hydroxy-nonanoic acid (9-HN) is derived as a separate compound and later esterified to monic acid to form pseudomonic acid. 13C labeled acetate feeding has shown that C1-C6 are constructed with acetate in the canonical fashion of fatty acid synthesis. C7' shows only C1 labeling of acetate, while C8' and C9' show a reversed pattern of 13C labeled acetate.[27] It is speculated that C7-C9 arises from a 3-hydroxypropionate starter unit, which is extended three times with malonyl-CoA and fully reduced to yield 9-HN. It has also been suggested that 9-HN is initiated by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric acid (HMG). This latter theory was not supported by feeding of [3-14C] or [3,6-13C2]-HMG.[28]

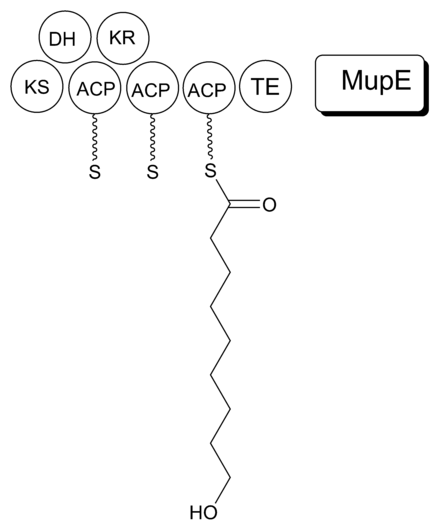

It is proposed that MmpB to catalyzes the synthesis of 9-HN (Figure 5). MmpB contains a KS, KR, DH, 3 ACPs, and a thioesterase (TE) domain.[22] It does not contain an enoyl reductase (ER) domain, which would be required for the complete reduction to the nine-carbon fatty acid. MupE is a single-domain protein that shows sequence similarity to known ER domains and may complete the reaction.[22] It also remains possible that 9-hydroxy-nonanoic acid is derived partially or entirely from outside of the mupirocin cluster.

References

- Fleischer, Alan B. (2002). Emergency Dermatology: A Rapid Treatment Guide. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 173. ISBN 9780071379953. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- "Drug Product Database Online Query". health-products.canada.ca. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Mupirocin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 298. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- Khanna, Ramesh; Krediet, Raymond T. (2009). Nolph and Gokal's Textbook of Peritoneal Dialysis (3 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 421. ISBN 9780387789408. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Heggers, John P.; Robson, Martin C.; Phillips, Linda G. (1990). Quantitative Bacteriology: Its Role in the Armamentarium of the Surgeon. CRC Press. p. 118. ISBN 9780849351297. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Mupirocin". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 178. ISBN 9781284057560.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Mupirocin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Hughes J, Mellows G (October 1978). "Inhibition of isoleucyl-transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase in Echerichia coli by pseudomonic acid". Biochem. J. 176 (1): 305–18. doi:10.1042/bj1760305. PMC 1186229. PMID 365175.

- "Product Monograph Bactroban" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- Troeman DPR, Van Hout D, Kluytmans JAJW (February 2019). "Antimicrobial approaches in the prevention of Staphylococcus aureus infections: a review". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74 (2): 281–294. doi:10.1093/jac/dky421. PMC 6337897. PMID 30376041.

- Cookson BD (January 1998). "The emergence of mupirocin resistance: a challenge to infection control and antibiotic prescribing practice". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41 (1): 11–8. doi:10.1093/jac/41.1.11. PMID 9511032.

- Worcester, Sharon (March 2008). "Topical MRSA Decolonization Is Warranted During Outbreaks". American College of Emergency Physicians. Elsevier Global Medical News. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- Yanagisawa T, Lee JT, Wu HC, Kawakami M (September 1994). "Relationship of protein structure of isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase with pseudomonic acid resistance of Escherichia coli. A proposed mode of action of pseudomonic acid as an inhibitor of isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase". J. Biol. Chem. 269 (39): 24304–9. PMID 7929087.

- Gilbart J, Perry CR, Slocombe B (January 1993). "High-level mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for two distinct isoleucyl-tRNA synthetases". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37 (1): 32–8. doi:10.1128/aac.37.1.32. PMC 187600. PMID 8431015.

- "Antibiotic Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes". ScienceOfAcne.com. 2011-06-11. Archived from the original on 2012-07-29. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- Haseltine WA, Block R (May 1973). "Synthesis of Guanosine Tetra- and Pentaphosphate Requires the Presence of a Codon-Specific, Uncharged Transfer Ribonucleic Acid in the Acceptor Site of Ribosomes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 70 (5): 1564–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.5.1564. PMC 433543. PMID 4576025.

- Tanaka K, Tamaki M, Watanabe S (November 1969). "Effect of furanomycin on the synthesis of isoleucyl-tRNA". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 195 (1): 244–5. doi:10.1016/0005-2787(69)90621-2. PMID 4982424.

- El-Sayed AK, Hothersall J, Cooper SM, Stephens E, Simpson TJ, Thomas CM (May 2003). "Characterization of the mupirocin biosynthesis gene cluster from Pseudomonas fluorescens NCIMB 10586". Chem. Biol. 10 (5): 419–30. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(03)00091-7. PMID 12770824.

- Cooper SM, Laosripaiboon W, Rahman AS, et al. (July 2005). "Shift to Pseudomonic acid B production in P. fluorescens NCIMB10586 by mutation of mupirocin tailoring genes mupO, mupU, mupV, and macpE". Chem. Biol. 12 (7): 825–33. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.015. PMID 16039529.

- Chain EB, Mellows G (1977). "Pseudomonic acid. Part 3. Structure of pseudomonic acid B". J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 (3): 318–24. doi:10.1039/p19770000318. PMID 402373.

- Clayton, J; O'Hanlon, Peter J.; Rogers, Norman H. (1980). "The structure and configuration of pseudomonic acid C". Tetrahedron Letters. 21 (9): 881–884. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)71533-4.

- O'Hanlon, PJ; Rogers, NH; Tyler, JW (1983). "The chemistry of pseudomonic acid. Part 6. Structure and preparation of pseudomonic acid D". Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1: 2655–2657. doi:10.1039/P19830002655.

- Feline TC, Jones RB, Mellows G, Phillips L (1977). "Pseudomonic acid. Part 2. Biosynthesis of pseudomonic acid A". J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 (3): 309–18. doi:10.1039/p19770000309. PMID 402372.

- Martin, FM; Simpson, TJ (1989). "Biosynthetic studies on pseudomonic acid (mupirocin), a novel antibiotic metabolite of Pseudomonas fluorescens". Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1 (1): 207–209. doi:10.1039/P19890000207.