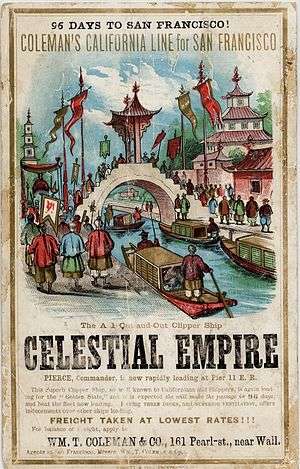

Celestial Empire (clipper)

Celestial Empire was a long-lived medium clipper ship built in 1852 for the San Francisco trade. She met with a variety of mishaps characteristic for ships of her era. A second ship by this name set a legal precedent regarding damage done by sailing ships coming in to dock.

Celestial Empire | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Celestial Empire |

| Owner: | C.H. Parsons & Co., New York City |

| Builder: | Jotham Stetson, South Boston, MA |

| Launched: | 1852 |

| Fate: | Abandoned 1878, en route to New York from Hamburg |

| General characteristics | |

| Tons burthen: | 1630 tons |

| Length: | 193 ft (59 m) |

| Beam: | 38 ft (12 m) |

| Draft: | 29 ft (8.8 m)[1] |

Troublesome crew, problematic voyage in 1874

Captain Barstow took charge of Celestial Empire at anchor off the Battery in New York for a voyage to San Francisco, October 27, 1874. She was carrying coal and timber, and had a crew of 26, including the captain, of various nationalities. The ship was over twenty years old at the time.

The outbound trip was not especially fast for a clipper ship. Captain Barstow notes the expected periods of calms, gales, and stormy weather at Cape Horn. Celestial Empire unloaded her cargo at Mare Island Navy Yard, near San Francisco, on March 22, 1875, and her bottom was re-coppered.

The new captain slated to relieve Barstow at San Francisco backed out of taking command of the ship. On May 27, 1875, Celestial Empire set sail in ballast for Callao, Peru, on a charter in the guano trade, arriving July 15, 1875. Barstow reported,

"While at Callao my crew were very troublesome and attempted to run away and a strict watch had to be kept on them, finding that they could not get away they complained of ill treatment and applied or complained to the Consul who came on board at their request through me."

The American Consul found in favor of the captain, saying

"I have come to the conclusion that they have not been treated badly - their conduct has bordered on insubordination and they have not complied with the conditions of their contract. They have no complaint to make about their food or the work that has been required of them, and there is every indication that their dissatisfaction arises from a desire to be discharged."

After boarding 3 new men to replace deserters, on July 27, 1875 the ship "left Callao for the Southern Guano Deposits and arrived at Point Lobos on the 12th of August".

For the month of September, Celestial Empire lay at anchor in rough water and could not load. Provisions were short, and crews on neighboring vessels were also "troublesome". The nearest provisions were eight miles away by open boat, at Pabellon de Pica, described as

"a collection of wooden shanties with gunny bag roofs and huts of mats without much roof and have all been put up since January 1875 when these southern deposits were first opened ... The town or village is situated on the beach behind a reef of rocks, that make a shelter for a boat landing when the surf is not too heavy. Some 30 persons were drowned by the upseting of the boats at the 3 deposits while I was there .. The Guano is loaded into launches of from 10 to 15 tons each direct from the deposits, and through shutes of canvass from the rocks to the Launches and is towed off by the Ship's boats and hoisted, or passed on board in tubs or baskets ..."-- a very dirty and dusty operation.

Finally, on October 6, two of Captain Barstow's seamen decided they had had enough of sitting on a rolling ship at the desolate guano deposits. They stole one of the ship's boats and left. Barstow never caught up with them, though not for lack of trying.

"Followed them the next day to Iquiqui 48 miles got trace of them then but could find neither the boat nor men, about 10 days after followed the coast up and found the boat in a small inlet at a small fishing village about 6 miles south of Iquiqui and reclaimed her after considerable trouble with the petty Peruvian authorities and paying them $25.00 half the value of the boat."

It was several months later, in March 1876, that the ship finally started loading—but not without incident.

"On the 15th of the month a heavy sea rolled in at about 12 midnight breaking a large kerosine lamp and setting fire to the ship. The rolling of the ship awoke me and I found the whole cabin in a blaze and the burning kerosine rolling over the floor. I immediately seized the bedding, blankets table covers, over coats &c and smothered the fire, the cabin was damaged myself slightly burned and much of my clothing damaged."

On the 8 July, Celestial Empire finished loading. After being surveyed, she was sent to Callao for final clearance, with a cargo of 2190 tons of guano. Captain Barstow once again found that the next captain was not eager to relieve him of his duties, and after reference to unspecified difficulties with local officials in Callao, for which protests were lodged, the narrative posted on the Library of Congress American Memory website breaks off.[2]

Receipt of Bibles

In March 1853, Celestial Empire, along with fifteen other vessels including clippers Highflyer, Antelope, Levanter, and Shooting Star, was supplied with Bibles by the American Seamen's Friend Society.[3]

Loss of the ship

Celestial Empire was abandoned on February 20, 1878. She was en route from Hamburg to New York.[1]

Rescue by the barque Templar

The crew of Celestial Empire was rescued by Captain Rufus P. Trefry, of the barque Templar, in February 1878, somewhere in the vicinity of Lat. 35° N., Long. 40° W. Templar was en route from Ipswich, UK, to Delaware Breakwater. According to Captain Trefry's account, he had sighted a large ship several times over the course of eight or ten days. On the morning of February 23, after a severe gale, Captain Trefry spotted the ship again at a distance. It was Celestial Empire, dismasted, having lost the top of the mizzen-mast and the mainmast at the deck level.

Templar approached Celestial Empire to offer assistance, only to discover that despite having one arm in a sling, Celestial Empire’s captain wanted to push on 600 miles east to the Azores with the dismasted vessel (of which he was partial owner), to the port of Fayal. Captain Trefry responded that Celestial Empire was in such bad shape, he wouldn’t accept the ship as a gift! At the time of the initial encounter, Celestial Empire was rolling too heavily for the crew to be taken off, due to the sea condition, and the lack of sails to steady her.

Captain Trefry indicated that he would stand by and await a signal. At 2 AM the next morning, the seas calmed sufficiently that Templar was able to get all 24 crew members off Celestial Empire, along with the dogs and hens. Additionally, a large quantity of stores was transferred to Templar in the ships’ boats.

Another gale hit at midnight that night, and it was two weeks later that sixteen members of the shipwrecked crew were unloaded by boat at Bermuda. The remainder were set ashore a week later, at Lewes, Delaware.

"About three months after this, while in the port of Calais. France, Captain Trefry received a cablegram from the owners of the derelict ship, as follows : "Gold watch and chain for you at American Legation, London." They were procured through the British Consul at Calais. The watch bore the inscription : "Presented by the President of the United States [ Rutherford B. Hayes ] to Captain R. P. Trefry, of the British barque Templar, in recognition of his brave and humane conduct in rescuing the officers and crew of the American ship Celestial Empire, February 23rd, 1878." Value of watch and chain, $300."[4]

Painting and photographs of the ships

- Watercolor of Celestial Empire, by Captain John E. Barstow

- Celestial Empire, photograph, State Library of Victoria, Australia

- Celestial Empire in Dundee Docks, photograph

Other ships named Celestial Empire

.jpg)

Two other ships were named Celestial Empire, an 1861 wooden full-rigged ship and an 1877 iron sailing vessel.[5] The 1861 ship carried immigrants from Bremen, Germany, to New York in 1872.[6] A sample of ash from the eruption of Krakatoa was preserved from the deck of the 1877 vessel.[7]

Mishap while docking

A tug brought Celestial Empire under tow to a wharf, alongside a schooner. The schooner’s rail was damaged, because Celestial Empire did not position her fenders properly, and the ship, not the tug, was held to be at fault.

The result was the court case Wilsey v. The Celestial Empire, 337.[8] which is featured in "A Treatise on the Law of Collisions at Sea", published in 1904.[9]

References

- Howe, Octavius T; Matthews, Frederick C. (1986) [1926-1927]. American Clipper Ships 1833-1858. Volume 1, Adelaide-Lotus. New York: Dover Publications. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-486-25115-8.

- Barstow, John E. (1876). "Remniscences". Coll. 67, v.1, Manuscripts Collection, G.W. Blunt White Library, Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc. American Memory, Library of Congress. Westward by Sea, A Maritime Perspective on American Expansion, 1820-1890. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- "New York Bible Society. Extracts from the report of Mr. John S. Pierson, Marine Agent", The Sailor's Magazine and Seamen's Friend, 21 (April): 236, 1854

- DesBrisay, Mather Byles (1895), "Account of rescues by Captain Rufus P. Trefery", History of the county of Lunenburg (2nd ed.), Toronto: W. Briggs, pp. 522–523

- Bruzelius, Lars. "Empire Line Fleet list". The Maritime History Virtual Archives. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- "Celestial Empire". Immigrant ship, Bremen, Germany to New York 13 July 1872. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- "Krakatoa". Krakatoa - a slide from the Quekett collection. Quekett Microscopical Club. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- Wilsey v. The Celestial Empire, 2 U.S. 651.

- Marsden, Reginald Godfrey (1904), "Tug and Tow, American Cases", A treatise on the law of collisions at sea (5th ed.), London: Stevens, p. 185