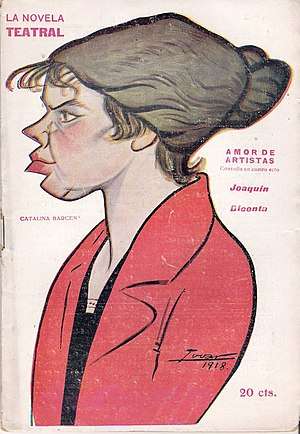

Catalina Bárcena

Catalina Bárcena (10 December 1888 – 3 August 1978 was a leading Spanish theatre actress during the early decades of the twentieth century. With her partner, Gregorio Martínez Sierra, she worked on the creation of the pioneering Teatro de arte company at Madrid's Teatro Eslava between 1916 and 1926. She subsequently starred with several other high-profile theatre companies and also, during the 1930s, built a Hollywood career as a film actress. In parallel with her acting career she became something of a fashion icon.[1][2]

Catalina Bárcena | |

|---|---|

ca. 1925 | |

| Born | 10 December 1888 |

| Died | 3 August 1978 (aged 89) |

| Occupation | actress |

| Spouse(s) | Ricardo Vargas |

| Children | 1. Fernando Vargas 2. Katia |

Life

Catalina Bárcena was born in Cienfuegos on Cuba, the child of small-scale farmers who had emigrated from Spain. In 1898, backed by the United States of America, Cuba ceased to be a Spanish colony. Around 1900 the family returned to their former home village of Santa María (Lebeña) in the mountains of northern Spain.

When she was twenty she moved to Madrid where, helped by family contacts, she embarked on an acting career with the theatre company of María Guerrero, participating in a number of premiers including "El genio alegre" ("The cheerful genius" 1906) and "Amores y amoríos" (1908) by the Quintero brothers, as well as "La araña" ("The Spider" 1908) by Àngel Guimerà,[3] "Las hijas del Cid" ("El Cid's daughters" 1908), "Doña María la Brava" (1909) and "En Flandes se ha puesto el sol" ("The sun has gone down in Flanders" 1910) - these last three by Eduardo Marquina. She was also in the cast for the premier performance of "La fuente amarga" ("The bitter fountain" 1910) by Manuel Linares Rivas.

Soon after that she formed her own theatre company. More premiers followed, including "La losa de los sueños" (1911) by Jacinto Benavente and "Flor de los pazos" (1912) by Rivas. From 1916 the scene of her major triumphs was Madrid's Teatro Eslava where plays that she premiered included "No te ofendas, Beatriz" (1920) and "Chica del gato" (1921), both by Carlos Arniches.

By 1916 Bárcena had teamed up with Gregorio Martínez Sierra, a playwright, publisher and stage director characterised by one source as "an even more unsuitable man".[2] The partnership was both professional and personal. Eight years her senior, Martínez Sierra drew respect as a progressive playwright at a time when most of the dramatists writing for the Madrid theatre were unadventurous and conservative. Martínez Sierra was married to the feminist writer and activist, María Lejárraga, who was understood to help her husband with his plays: there are suggestions from some quarters that she wrote them. Lejárraga was disinclined to agree to a divorce, and while Martínez Sierra and Bárcena cohabited openly, his wife took to describing herself, just as openly, as her husband's widow.[2]

Bárcena introduced more works by Martínez Sierra to the Madrid stage, along with pieces by Benito Pérez Galdós and Jacinto Benavente. One of her lover's contributions to the Spanish stage was as a translator: Bárcena featured in premiers of important foreign plays such as Ibsen's Doll's House (1917) and Shaw's Pygmalion (1920). The partnership with Martínez Sierra also gave rise to a succession of further premiers of plays by a younger generation of Spanish writers during the 1920s. One was of "El maleficio de la mariposa" ("The Curse of the Butterfly"), generally identified as the first play by Federico García Lorca, in a production that used memorable costumes designed by Rafael Barradas. As early as 1916 Bárcena and Martínez Sierra were involving themselves in the newly popular genre of pantomime, blending the traditions of musical theatre and spoken stage works.

In 1922 she gave birth to her daughter, Katia. The father of the infant was Martínez Sierra. It was partly to get away from the scandal generated by the illegitimate birth that in 1926 Catalina Bárcena embarked on a tour of South America. Costume and clothes were important to her, and she was accompanied by her wardrobe mistress, Antonia García.[2] She was presumably well received by theatre audiences, since the South American tour lasted three years. By the time she returned to Madrid, commercial theatre was in crisis. The international cinema industry was undergoing traumas of its own, reflecting the switch from silent movies to "talkies". Bárcena had always sworn that she would have nothing to do with cinema, but in California the major studios were desperately confronting the reality that many of the top stars of the silent screen lacked the voice projection and other vocal talents appropriate for the new technologies.[2][4] In 1927 she signed up with Fox, starring in a succession of Spanish language movies including versions of "Canción de cuna" and "The Merry widow".[5] However, the Hollywood roles dried up during the later 1930s as younger Spanish-language stars appeared on the scene.[2]

During the Civil War she chose to go into exile, accompanying her sister María Luisa de la Cotera. Maria Luisa was married to a Catalan ship's captain whose father was Juan Antonio Molinas Soler, President of the Port of Barcelona, of the New Vulcano shipyards and of the "Association of Industrial Engineers" ("Asociación de Ingenieros Industriales"). Through his connections they were able to leave the country, apparently accompanied by Bárcena's lover, Gregorio Martínez Sierra, arriving at Oran and settling in Tétouan in 1936. Morocco was less brutally disrupted by the fighting than Spain itself. Nevertheless, Bárcena and Martínez Sierra did not long remain with her sister's family, preferring to make their ways at various stages in Marseilles, Paris and Buenos Aires where they remained for nearly a decade. The two of them went back to Madrid only in 1947. By this time Martínez Sierra was ill with cancer and he died a few weeks after their return.[2]

Bárcena was approaching conventional retirement age and there was no return to her pre-war stardom, but she remained actively engaged in the world of theatre. In 1948 she formed the "Compañía Cómico-Dramática Española" comic theatre company, with herself as its leading actress. The company had its debut at the Madrid Comedy Theatre ("Teatro de la Comedia") with "Pygmalion", followed in 1949 by another foreign play, "Fifty Years of Happiness". In 1954 they presented " Leyenda de una vida" ("Story of a life") at the city's Teatro Infanta Isabel.

In 1971 or 1972 she received the National Theatre Prize.[1][2] After she died in 1978, one of the most memorable epitaphs was penned by Lorca, by now himself something of a "grand old man" of the theatre, who dedicated a poem to her memory in which he recalled her voice as having "sounded like music and crystal" ("sonaba a música y cristal").[1]

Personal

While working at the company of María Guerrero, Catalina Bárcena was noticed by Guerrero's loose-living husband, the actor Fernando Díaz de Mendoza y Aguado. She christened their son Fernando. Fernando Díaz de Mendoza y Aguado had sons by various women: they were all christened Fernando.[6] Meanwhile, Catalina hastily married not her boss's husband, but a more junior actor in the company, called Ricardo Vargas. By 1916 the couple were evidently separated,[2] although they were divorced only in 1932.[1]

References

- "Los trajes "malditos" de la diva adúltera". Mundinteractivos, S.A. (El Mundo), Madrid. 1 February 2004. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Meredith Etherington-Smith (27 October 2012). "A treasure trove of vintage Lanvin dresses up for auction". story of love, scandal and Hollywood stardom lies behind an early-20th-century collection of Lanvin couture that is about to come to auction at Christie's. Daily Telegraph (online). Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "Notas teatrales". Diario ABC. 16 April 1908. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "Catalina Bárcena". Biografías y Vidas. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Juan de Mata Moncho Aguirre (2000). "Las adaptaciones de obras de teatro español en el cine y el". Tesis de Doctorado. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Antonina Rodrigo; Arturo del Hoyo (prologue) (April 2005). María Lejárraga: una mujer en la sombra. Algaba Ediciones. p. 108. ISBN 84-96107-38-8.