Caryodendron orinocense

Caryodendron orinocense, commonly known as cacay, inchi or orinoconut, is an evergreen tree belonging to the family Euphorbiaceae.

| Caryodendron orinocense | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cacay fruits, near Puerto Gaitán, Meta, Colombia. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Genus: | Caryodendron |

| Species: | C. orinocense |

| Binomial name | |

| Caryodendron orinocense | |

| |

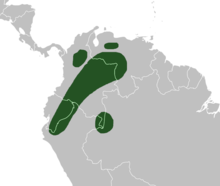

| Approximate distribution of Caryodendron orinocense[1] | |

This species of flowering plant is indigenous to the north-west of South America, particularly from the drainage basins of the Orinoco and Amazon rivers located in Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru and Brazil. Originally described by Hermann Karsten in 1858, the cacay tree distinguishes itself by its dense and leafy top, as well as its production of fruits, each one containing three edible nuts. Cacay is notable for the oil extracted from its nuts, which is edible and is also used in cosmetics.

Description

Caryodendron orinocense is a tree which can grow to 30–40 metres (100–130 ft) tall in the forest.[2] In plantations, the tree reaches heights of up to 15 metres (50 ft).[3] Its trunk is straight and cylindrical before separating into numerous branches.[2] Its outer bark is smooth, and is periodically shed as laminar plates. It possesses a wide and superficial root system, such that its thick roots are sometimes visible above ground.[2] The longevity of the species exceeds 60 years.[4]

Cacay is an evergreen tree and has a dense and leafy crown.[4] Its leaves are simple and are arranged in an alternate pattern on the stem. Their shape is elliptical or oval, between 12–25 centimetres (4.7–9.8 in) long and 4–10 centimetres (1.6–3.9 in) wide.[3]

It is a dioecious plants, with male and female specimens. Its masculine flowering is a terminal raceme with small greenish flowers between 2.5–3.5 millimetres (0.098–0.138 in) in diameter. Neither male nor female flowers display any petals. Its feminine flowering is a terminal ear, also with greenish flowers ranging between 2.5–3.5 millimetres (0.098–0.138 in) in diameter, containing large and persistent bracts.[2]

Its fruit is a brownish/grey oval and woody capsule between 3.2–4.5 centimetres (1.3–1.8 in) in diameter. Each fruit contains three nuts or kernels (rarely two or four), which are slightly convex and have three faces.[2][5] Each nut contains a single seed covered by a testa and weights approximately 2.7 grams (0.095 oz).[6]

Taxonomy and etymology

The species Caryodendron orinocense was described in 1858 by the German botanist Hermann Karsten, and was published in Florae Columbiae.[7] In its scientific name, the term Caryodendron is derived from the ancient Greek káryon, meaning "nut", and déndron, meaning "tree". Its epithet orinocense suggests that the species was first identified near the Orinoco river.[4]

Caryodendron orinocense is found under the following phylogenetic tree within the Caryodendreae tribe.[notes 1] The number in parenthesis represents the year in which the species was described.[9][10]

| Caryodendreae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Common names

The vernacular names of Caryodendron orinocensese include:

Distribution, habitat, and ecology

Cacay is an indigenous species to the drainage basins of the Orinoco and Amazon rivers, and can be found in Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru and Brazil.[12] In Colombia, cacay is distributed across the Piedemonte llanero[notes 3] in the eastern foothills of the Andes Mountains.[23] It is also found in the watershed of the Magdalena River.[1] The species has been reported in five Colombian departments (Antioquia, Caquetá, Cundinamarca, Meta, Putumayo) with influence over three Colombian natural regions (Andean, Orinoquía or Eastern Plains, and Amazon).[24] In Venezuela, the plant grows in the states of Apure, Lara, y Barinas.[20][23] Cacay can also be found in Ecuador, Peru and Brazil in the western part of the Amazon river watershed.[3][25]

The tree grows in the transition between tropical moist forest and tropical wet forest, receiving an average annual precipitation of 2,000–5,000 millimetres (80–200 in).[3][26] It develops preferably in terrains with good drainage that do not easily flood.[3] It tolerates a few months of moderate drought, but does not support long dry periods. The species is also able to support short periods of water saturation, but cannot withstand permanent waterlogging.[2][3] Cacay prospers in fertile soils originating from alluvial deposits, but can adapt to ultisol and oxisol soils which are acidic and poor in nutrient content.[23]

Cacay develops best in warm climates and in low-altitude plains, with average temperatures of 22–28 °C (72–82 °F) and relative humidity of 70-90%.[25][27] However, cacay is found in altitudes ranging from sea level to 2300 m a.s.l.[3]

Propagation

Under natural conditions, the reproduction of cacay is sexual; its seeds germinate well on the ground, one to two weeks after falling from the tree.[2][15] The species' seeds are recalcitrant, as the seeds quickly lose their viability when under storage.[2][28] A study conducted in 2012 by Judith García and Carmen Basso concluded that cacay seeds tolerate up to eight days of storage before losing viability, preferably in temperatures of 12–13 °C (54–55 °F).[28]

The species can also reproduce through vegetative (asexual) means, especially through grafting, which is commonly used in cacay farming.[3][15] Conversely, propagation by plant cutting does not yield satisfactory results, as even when the plant shows callus growth, it does not produce any new development of roots or buds.[15][29]

Farming

The cultivated cacay tree initially grows slowly. During this stage, moderate shade favorably contributes to its development.[15][21] Cacay can be planted in bags in a nursery for approximately one year, until the tree reaches a height of about 50 centimetres (20 in).[30] When the tree is actively producing fruits, the cacay plant is a heliophyte, although it tolerates some shade. Cacay be planted in parallel with another plant that grows rapidly and that possesses a small crown which may provide shade to the juvenile cacay tree, but which does not compete for sunlight during the cacay's adult stage.[15] Some plantations associate the cacay tree with another crop that may provide a live vegetable groundcover,[notes 4] for example kudzu.[15]

The ripe cacay fruit physiologically separates itself from the plant and falls to the ground.[3] Cacay trees begin to produce fruit at ages 4-7 years. A single 10 year old cacay tree may produce 100–250 kilograms (220–550 lb) of nuts per year,[30] although some trees have been reported to produce up to 800 kilograms (1,760 lb) of nuts per year.[3]

Properties and uses

Cacay oil

Cacay is renowned for the quality of its plant oil.[5] Each cacay fruit generally produces three nuts, from which a liquid oil with a yellow-greenish color can be extracted.[2] This oil comprises between 40-60% of the seed's weight.[2][3][23] Several studies (Pérez 2001, Cisneros Torres 2006) report that the cacay oil is composed of 71-75% of linoleic acid, an essential fatty acid from the omega-6 fatty acid family, which is important for skincare purposes.[6][8][20] Other studies have reported linoleic acid content of 58% (Medeiros de Azevedo 2020) and 85% (Radice 2014).[32][33] This high concentration of polyunsaturated fats (in this case, of linoleic acid) is superior to that of soybean oil (60%), corn/maize oil (55.5%), sesame oil (42%), peanut oil (26%), coconut oil (14%), olive oil (9.5%), and palm oil (8%).[3]

Cacay oil is used in the production of cosmetic products such as soaps, sunscreens, and skincare creams.[21] The full value proposition of this oil for cosmetic purposes is still being developed; however, various studies (Pérez 2001, Ortega Álvarez 2014) have already remarked on the future potential of cacay in this field.[11][20] The cacay oil is also used directly as an edible oil.[3][21]

Nutrition

| Properties | Quantity |

| Plant oil | 40-60%[2][3][23] |

| Polyunsaturated fat (in the oil) | 71-75%[6][8][20] |

| Calories per nut | 641-691[8][27] |

| Protein | 15-19%[6][8][19] |

| Starch | 17%[8] |

The cacay nut is rich in phosphorus, calcium, and iron.[8][27] About 15-19% of the nut is composed of protein, while the press cake (the dry organic matter after the oil is extracted) is composed 43-46% of protein.[3][8] The nuts from ripe cacay fruits are edible and have a pleasant taste, similar to that of peanuts.[3][27] Nuts can be eaten uncooked, toasted, fried, or boiled with salt. The nuts can also be used to prepare foods such as cakes, turrón, beverages, and cookies. After grinding down the nut, its flour can be used to produce vitamin supplements, as well as to elaborate functional foods.[13]

Other uses

Its lumber can be used for woodworking structures, and may be utilized as firewood and in the production of charcoal.[5][23] Cacay trees may also be used to provide shade to other crops that need it (as possibly coffee plantations) and for other animals.[23][30] Within the domain of agroforestry, cacay trees may be introduced into areas that are not adequate for intense agricultural and cattle raining activities.[23] Furthermore, the tree also attracts bees through the nectar excreted from its leaves, aiding in the tree's pollination.[21] Lastly, the nut's press cake can also serve as food for cattle due to their high content of proteins and minerals.[21]

Ecological value

Cacay has been identified as one of the several trees indigenous to the Eastern Plains region of Colombia that may serve in the ecological restoration of areas of the savanna containing invasive species of grasses such as brachiaria humidicola.[34] Crops of Caryodendron orinocense, as well as those of other native trees, may help in the conservation and reforestation of their area's ecosystem.[35]

Notes

- In some sources, the scientific name Dioicia tetrandia L. appears as a synonym of Caryodendron orinocense.[2][8]

- Caryodendron orinocensese (commonly known as cacay, inchi, or orinoconut) should not be mistaken with Plukenetia volubilis, which is commonly known as sacha inchi.[16]

- The Piedemonte Llanero is a wedge duplex zone on the eastern flank of the Eastern Ranges of Colombia.[22]

- A cover crop is a crop that provides a vegetable coverage of the ground, whether temporary or permanent, and which is planted in association with another crop.[31]

References

- "Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) & IUCN SSC Global Tree Specialist Group 2019. Caryodendron orinocense". IUCN Red List. Retrieved 13 November 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Especies forestales productoras de frutas y otros alimentos 3. Ejemplos de America Latina (in Spanish). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1987.

- Ávila, Luz María; Díaz Merchán, José Andrés (2002). "Sondeo del mercado mundial de Inchi (Caryodendron orinocense)" (in Spanish). Alexander von Humboldt Biological Resources Research Institute. Retrieved 29 March 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Catálogo virtual de flora del Valle de Aburrá" (in Spanish). Universidad EIA. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Jiménez, Luis Carlos; Yesid Bernal, Henry (1992). El "inchi", Caryodendron orinocense Karsten (Euphorbiaceae): la oleaginosa mas promisoria de la subregion andina. 2nd (in Spanish). Programa de Recursos Vegetales del Convenio Andres Bello.

- Cisneros Torres, Diana Evelin; Díaz Hernández, Andrea Del Rosario (2006). "Obtención de aceite de la nuez Caryodendron Orinocense originaria del Departamento del Caquetá en la Planta Piloto de la Universidad de La Salle" (in Spanish). La Salle University. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Caryodendron orinocense". Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Martínez S., J.B. (1979). "El inchí (Caryodendron orinocense Karst)". Corporación Forestal de Nariño (in Spanish).

- "Caryodendron H. Karst. - Subordinate Taxa". Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN-Taxonomy). National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland. 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ortega Álvarez, Deysi D (2014). "Caracterización de la composición fitoquímica del aceite vegetal de la especie maní de árbol (Caryodendron orinocense h. Karst) e investigar su aplicación en emulsiones cosméticas" (in Spanish). Universidad Estatal Amazónica. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Losada A., Pablo (2016). "Inclusión de torta de Cacay (Caryodendron orinocense) en la degradación in vitro in situ de la materia seca" (in Spanish). University of Applied and Environmental Sciences. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Garcia Urrea, Lili Johanna; Martinez Tamara, Ferney Eduardo (2017). "El Cacay en bebidas funcionales y su uso gastronómico" (in Spanish). Universitaria Agustiniana. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Morillo-Coronado, Ana Cruz (2015). "Caracterización molecular con microsatélites amplificados al azar (RAMs) de Inchi (Caryodendron orinocense K.)" (in Spanish). Revista Colombiana de Biotecnología. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gonzáles Coral, Agustín; Torres Reyna, Guiuseppe Melecio (2010). "Manual de cultivo de metohuayo Caryodendron orinocense Karst" (in Spanish). Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wang, Sunan; Zhu, Fan; Yukio, Kakuda (2018). "Sacha inchi (Plukenetia volubilis L.): Nutritional composition, biological activity, and uses". Food Chemistry. 265: 316–328.

- Reckin, J. (1983). "The Orinoconut - A promising tree crop for the Tropics". International Tree Crops Journal. 2 (2): 105–119. doi:10.1080/01435698.1983.9752746.

- Janick, Jules; Paull, Robert E. (2008). Cabi Publishing (ed.). Encyclopedia of Fruit and Nuts. pp. 366–368. ISBN 978-0-85199-638-7.

- Padilla, F.C.; Alfaro, M.J.; Chávez, J.F. (1998). "Composición química de las semillas del nogal de Barquisimeto (Caryodendron orinocense, euphorbiaceae)" (in Spanish). Journal of Food Science and Technology. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pérez, M.N.; Alfaro, M. de J.; Padilla, F.C. (2001). Evaluation of ’Nuez de Barinas’ (Caryodendron Orinocense) Oil for Possible Use in Cosmetic. International Journal of Cosmetic Science.

- Alzuru, Angel (September 2007). "Nueza criolla, Diagnóstico participativo de su situación en el estado Lara, Venezuela". Centro para la Gestión Tecnológica Popular (CETEP) (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Kellogg, James; Egbue, Obi (May 2012). "Three-dimensional structural evolution and kinematics of the Piedemonte Llanero, Central Llanos foothills, Eastern Cordillera, Colombia". 39: 216–227. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2012.04.012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pabon E., Miguel A. (1982). Oleaginosas de la Amazonía: el inchi (in Spanish). Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria.

- "Catálogo de Plantas y Líquenes de Colombia". catalogoplantasdecolombia.unal.edu.co (in Spanish). National University of Colombia. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- Orduz R., Javier Orlando; Rangel M., Jorge Alberto (2002). Frutales Tropicales Potentiales para el Piedmonte Llanero (in Spanish). Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria.

- Nieto, V.M.; Rodriguez, J. El inchí (Caryodendron orinocense Karst). Tropical Tree Seed Manual - Species Descriptions.

- "Fichas Tecnicas de Especies de uso Forestal y Agroforestal de la Amazonia Colombiana: Inchi" (PDF). sinchi.org.co (in Spanish). Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas «Sinchi». Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- García, Judith J.; Basso, Carmen (2012). "Caracterización de la viabilidad de semillas de inchi (Caryodendron orinocense Karsten) de dos procedencias". Revista Cientifica UDO Agricola (in Spanish). 12.

- García, Judith J.; Moratinos, Humberto; Perdomo, Dinaba (2009). "Evaluación de dos métodos de propagación asexual en inchi (Caryodendron orinocense Karsten)" (in Spanish). Central University of Venezuela. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Geilfus, Frans (1994). "El árbol al servicio del agricultor: manual de agroforesteria para el desarrollo rural. Tome 2" (in Spanish). Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (CATIE). ISBN 9977-57-174-0. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pound, Barry. "Cultivos de Cobertura para la Agricultura Sostenible en América" (in Spanish). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 29 March 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Medeiros de Azevedo, Wendell; Ribeiro de Oliveira, Larissa Ferreira; Alves Alcântara, Maristela (2020). "Physicochemical characterization, fatty acid profile, antioxidant activity and antibacterial potential of cacay oil, coconut oil and cacay butter". PLoS ONE. 15 (4). Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Radice, Matteo; Viafara, Derwin; Neill, David (2014). "Chemical characterization and antioxidant activity of Amazonian (Ecuador) Caryodendron orinocense Karst. and Bactris gasipaes Kunth seed oils". Journal of Oleo Science. 63 (12): 1243–1250. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Angulo-Ospina, Carlos Alberto; Silva-Herrera, Luis Jairo (2016). "Crecimiento de cuarenta especies forestales nativas, aptas para restauración en la Orinoquia colombiana". Colombia Forestal (in Spanish). 19 (S1): 15. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Espinosa, Rocío; López, Andrés M. (2019). Arboles nativos importantes para la conservación de la biodiversidad: Propagación y uso en paisajes cafeteros. Centro Nacional de Investigaciones de Cafe (Cenicafé) (in Spanish). ISBN 978-958-8490-37-3. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Caryodendron orinocense |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caryodendron orinocense. |

- «Caryodendron orinocense H. Karst.», Encyclopedia of Life.

- «Caryodendron orinocense Karst.», Global Biodiversity Information Facility.