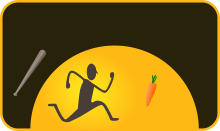

Carrot and stick

The phrase "carrot and stick" is a metaphor for the use of a combination of reward and punishment to induce a desired behavior.

The carrot-and-stick principle is this: the stick is tied to the bridle of a mule or donkey, or held by the human rider or cart driver so that it extends above and in front of the animal's head, and the carrot hangs on a string from the far end of the stick, just out of reach of the pack animal's mouth. Attracted by the sight and smell, the donkey steps forward to bite at the carrot, but as it is attached to the stick, the carrot also moves forward and remains out of reach. Not especially brilliant, the beast repeats the same ineffective strategy ad infinitum, thereby pulling or carrying whatever or whomever it's laden with, until the poor animal collapses from exhaustion.

Thus, the metaphor can serve as a visualization of what can sometimes happen in corporate and other settings, with executives "dangling" a promotion, for example (the "carrot") in front of the rank and file in order to get massive amounts of work out of them in exchange for very little reward. In general usage, any promised reward that is really a tease may be referred to as a "dangling carrot."

In more contemporary times, the phrase has been broadly amended to "carrot or stick," an illustration of an authority figure holding a reward (the carrot) in one hand and a punishment (the stick) in the other, to signify a no-brainer of a choice presented to the other party. For example, in politics, "carrot or stick" sometimes refers to the realist concept of soft and hard power. The carrot in this context could be the promise of economic or diplomatic aid between nations, while the stick might be the threat of military action.

Origin

The earliest English-language references to the "carrot and stick" come from authors in the mid-1800s who in turn wrote in reference to a "caricature" or cartoon of the time that depicted a race between donkey riders, with the losing jockey using the strategy of beating his steed with "blackthorn twigs" to urge it forward, while the winner of the race sits in his saddle relaxing and holding the butt end of his baited stick.[1][2] In fact, in some oral traditions, turnips were used instead of carrots as the donkey's temptation.

Decades later, the device appeared in a letter written by Winston Churchill dated July 6, 1938, worded in such a way as to possibly bolster the "carrot or stick" side of later debates: Churchill writes, "Thus, by every device from the stick to the carrot, the emaciated Austrian donkey is made to pull the Nazi barrow up an ever-steepening hill."[3]

The Southern Hemisphere caught up in 1947 and 1948 amid Australian newspaper commentary about the need to stimulate productivity following World War II.[4][5]

The earliest uses of the idiom in widely available U.S. periodicals were in The Economist's December 11, 1948 issue and in a Daily Republic newspaper article that same year that discussed Russia's economy.[6]

In the German language, the idiom translates as sugar bread and whip.

Examples

In the years leading up to World War II and during the war itself, Joseph Stalin applied the "carrot or stick" principle among the nations of the Soviet Sphere of Influence in order to establish tighter control over them. For example, in 1934, Stalin reversed his decision to attack the socialists of the region, instead allowing them to join the "People's Front Against Fascism and War." Despite this alliance's limited success when it came to strategies against the fascism of Nazi Germany, Stalin had effectively replaced the "stick" of aggression that he had been using against the socialists with the "carrot" of a better deal for them: membership in a more sweeping system of Popular Fronts against the Axis.

Stalin's use of reward and punishment, as described above, has not been unique in the world arena. A casual survey of international news confirms that the tactic is still in common use today, by people in power up to and including the presidents of the United States and NATO.

The carrot and stick as metaphor could be applied to the conduct of the Chinese during the Ming treasure voyages in the 15th century.[7] The carrot was trade opportunity and the stick was the overwhelming naval power that the Ming Chinese expeditionary fleet could bring upon recalcitrant rulers.[7] Diplomatic relationships were based on a mutually beneficial maritime commerce and a visible presence of a Chinese militaristic naval force in foreign waters.[8] The Chinese naval superiority was a crucial factor in this interaction, namely because it was inadvisable to risk punitive action from the Chinese fleet.[9] Meanwhile, the worthwhile and profitable nature of the Ming treasure voyages for foreign countries was a persuading factor to comply.[8]

See also

- Abusive power and control

- Aversives

- Classical conditioning

- Feedback loop

- Norm of reciprocity

- Operant conditioning

- Psychological manipulation

- Stick licensing

- Throffer, a combination of a threat with an offer

- Two-way communication

References

- Montague, Edward P. (1849). Narrative of the late expedition to the Dead Sea: From a diary by one of the party. Carey and Hart. p. 139.

Edward p Montague the idea that persuasion is better than force.

- Child, Lydia Maria (1871). The Children of Mount Ida: And Other Stories. Charles S. Francis.

- Safire, William (December 31, 1995). "On Language – Gotcha! Gang Strikes Again". New York Times. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Douglas wilkie's News Sense UK Workers Must Produce More". The Daily News. 1947-08-05. p. 5. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- "Increased Productivity". Daily Advertiser. 1948-02-14. p. 2. Retrieved 2015-12-14.

- "Marxist Socialism Abandoned, Russian Economy Capitalistic (1948) - on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- Bowring, Philip (2019). "Tremble and Obey: The Zheng He Voyages". Empire of the Winds: The Global Role of Asia’s Great Archipelago. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781788314466.

- Wang, Gungwu (1998). "Ming Foreign Relations: Southeast Asia". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1398–1644, Part 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 320–321. ISBN 978-0521243339.

- Sen, Tansen (2016). "The Impact of Zheng He's Expeditions on Indian Ocean Interactions". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 79 (3): 632. doi:10.1017/S0041977X16001038.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carrot and stick. |

- EconPapers abstract for an experiment using this model "The Carrot or the Stick: Rewards, Punishments, and Cooperation"